China Miéville: Marx’s Communist Manifesto Has Much To Teach Us In 2023

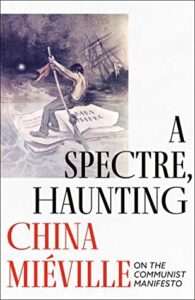

“The Communist Manifesto” is one of the most widely read political documents in the history of the world. It influenced millions of people against capitalist oppression and toward a more just and humane social order. It is also a brilliant display of literary and poetic expression by its author, the German revolutionary philosopher Karl Marx, which few, if any, political commentators since have been able to match. But is “The Communist Manifesto” politically relevant today? The renowned British and New York Times-bestselling author of “weird fiction” and non-fiction books China Miéville thinks so, which is why he wrote his latest book, A Spectre, Haunting: On the Communist Manifesto, published in May 2022 by Haymarket Books. The book, incidentally, has been described — correctly so, I might add — as “a lyrical introduction and a spirited defense of the modern world’s most influential political document.”

“The Communist Manifesto” is one of the most widely read political documents in the history of the world. It influenced millions of people against capitalist oppression and toward a more just and humane social order. It is also a brilliant display of literary and poetic expression by its author, the German revolutionary philosopher Karl Marx, which few, if any, political commentators since have been able to match. But is “The Communist Manifesto” politically relevant today? The renowned British and New York Times-bestselling author of “weird fiction” and non-fiction books China Miéville thinks so, which is why he wrote his latest book, A Spectre, Haunting: On the Communist Manifesto, published in May 2022 by Haymarket Books. The book, incidentally, has been described — correctly so, I might add — as “a lyrical introduction and a spirited defense of the modern world’s most influential political document.”

Miéville studied at Cambridge University and received a Ph.D. in international relations from the London School of Economics. He has published scores of highly acclaimed fiction works, such as King Rat (1998), which was nominated for both the International Horror Guild and Bram Stoker Awards for best first novel; Perdido Street Station (2000), which won the 2001 Arthur C. Clarke award for best science fiction and a 2001 British Fantasy Award; Iron Council (2004), winner of the Arthur C. Clarke award and the Locus Award for Best Fantasy Novel; The City & the City (2009), a further winner of an Arthur C. Clarke award, Hugo Award and World Fantasy Award for Best Novel; and The Last Days of a New Paris (2016). A self-proclaimed Marxist, Miéville has also published Between Equal Rights: A Marxist Theory of International Law and October: The Story of the Russian Revolution.

In this exclusive interview for Truthout, Miéville discusses his latest book, why it’s still important to engage with “The Communist Manifesto” and why we must approach ecological catastrophe with radical theory.

C. J. Polychroniou: “The Communist Manifesto,” originally known as the “Manifesto of the Communist Party,” was written by Karl Marx with the assistance of Friedrich Engels and published in London on February 21, 1848. Its original aim was to serve “as a complete theoretical and practical party program” for the Communist League, but ultimately became the principal political pamphlet for the European communist parties in the 19th and 20th centuries. It is also widely recognized as one of the most important and influential political documents in the history of the world. Of course, history has taken a very different route from that envisioned by Marx and Engels. True, communism (or some variant of it!) was tried out in different parts of the world, but capitalism still reigns supreme. With that in mind, what prompted you to write a book on “The Communist Manifesto” in the second decade of the 21st century? Historical curiosity or political relevance?

China Miéville: There’s no necessary contradiction between the two, of course. I do think that the manifesto should be an object of historical curiosity to anyone interested in the shaping of the modern world, and/or of great and historical ideas. And to that extent, I’m well aware that plenty of potential readers of A Spectre, Haunting will be highly skeptical about communism in any form, and thus of the modern applicability of the book.

Part of the argument is that it is still worth engaging with the manifesto. To preempt the second half of this answer, I disagree with that sense that it’s a purely historical curiosity, for reasons that I try to make clear in the book. But I’ve also long been frustrated by the profoundly dunderheaded and either bad faith or ignorant (or both) nature of the so-called debates around the manifesto. One of the ideas of this book is to say precisely to people who do not see the pamphlet as politically relevant that the great majority of the arguments usually adduced for that position are just intellectually lazy and embarrassing, and that surely it is critics who should give their intellectual and political opponents the courtesy of taking them on at their strongest, and with the most curious and generous and engaged reading, rather than airily reciting completely unthinking bromides and nostrums. I hope if I were to pronounce on a book with which I profoundly disagreed, I would try to engage with it seriously.

All of which is to say that I hope A Spectre, Haunting invites an engagement from people who profoundly disagree with me, and with the manifesto, at a serious, interesting and worthy level. In other words, even if you don’t find anything politically relevant in the manifesto, you can’t, surely, dismiss its historical and social importance, and if the book does nothing else than to plead for a more serious discussion of it at that level, I would be pleased. Because — again, as I try to say and illustrate in A Spectre, Haunting, and with some honorable exceptions — most of the discussions of the manifesto from its critics, including very celebrated critics and those who, I think, should know far better, is based on piss-poor and miserly reading.

Of course, on top of that, I absolutely do think that the manifesto remains politically relevant. Indeed, inspirational. Not that I have, or anyone should have, an uncritical or dogmatic relationship to it. In the book, I try to make clear the various ways in which, and issues on which, I think the manifesto is inadequate, or contradictory, or simply wrong. But for me, the manifesto read as it deserves to be read, flawed and rushed and partial as it is, is a work of incredible political importance — as well as great literary urgency and beauty.

Every day, capitalism proves that it is absolutely indifferent to human flourishing, or life, and therefore it really shouldn’t be a surprise that so many of the grotesque and monstrous phenomena of our society — inequality, racism, misogyny, imperialism, ecological catastrophe, mass extinction, mass unnecessary death — are inextricable from capitalism. The demand for a system that prioritizes human need over profit is a demand for the end of capitalism. We can debate what that might look like, but if we take seriously the idea that the only way to get to a world fit to live in is to get beyond capitalism, we have to move beyond the “common sense” — which is to say, the deadening propaganda — that it is “obviously” impossible to have anything other than capitalism. The manifesto’s unremitting insistence on the dynamics of class history that got us here, and its ruthless denaturalizing and questioning of supposedly eternal truths, all in the service of liberation, is profoundly important.

“Workers of All Countries, Unite” is one of the most fundamental political slogans of “The Communist Manifesto.” Was this a call for world revolution or merely political rhetoric? Indeed, there is an entire genre of political writing devoted to the idea that Marx was actually in favor of restricting immigration (Irish immigration, as a case in point) because it was driving down wages for (English) workers. Do you have any thoughts on this matter? Would Marx be favoring immigration restrictions today?

It was certainly not “mere” rhetoric, though it was part of a rhetorical masterwork. But it was rhetoric deployed as part of — whether you agree with it or not — an absolutely sincere political project, a commitment to world revolution. On the vexed question of Marx and immigration: Mature Marx was absolutely and explicitly clear that English workers’ racism against Irish workers was a profound plank in their own oppression and had to be overcome before political liberation could be pursued. In addition, he and Engels were unstintingly suspicious of the bourgeois state, which of course is the proponent, perpetrator and police of immigration controls. I think Marx and Engels would treat immigration restrictions today with the contempt and suspicion that, as tools predicated on and bolstering racism, and that undermine the international solidarity of the working class — which, the manifesto insists, “has no country” — they deserve. That said, it’s worth stressing that I’m very suspicious of the kind of apologetic theology approach to Marxism that tries to derive a political position today from what Marx would or would not have thought. First of all, the judgment of what he “would have thought” (which has a discomfiting hagiographical ring to it) always involves an act of historical translation at very best, and violence at worst: because context is everything. Fredric Jameson is right: always historicize. Secondly, because it’s hardly surprising that one could find in Marxism as a system an indispensable tool for analysis, and also disagree with Marx — even if we could be confident in what he would say — in particular concrete instances. The key points are what the truth is, and what is the best political approach in principle and strategically and tactically. Without question, finding as I do such great resources in the Marxist tradition, I think that Marx’s opinions are crucial data with regard to that, but it’s perfectly possible to cleave to the method and tradition, and yet to disagree with Marx on this or that.

As noted earlier, communism was tried out in different parts of the world throughout the 20th century. From your own perspective, was Marx’s vision of communism realized in any form or shape under “actually existing socialism” regimes?

Simply put, no. That’s not an adequate answer, of course. And to be clear, though I do go into this a little bit in my book, in-depth of the “actually existing socialisms” is some way beyond its remit, so I’m not pretending to have made a conclusive argument on this issue. What I do want to do is stress what I think should be a given starting point for any good-faith debate, but which absolutely isn’t, which is that seeing those regimes as “communist” simply because they say so is absolutely absurd. It’s absurd whether that’s from the side of critics, who use it to argue that communism is inevitably oppressive, or from the side of apologists and partisans, who take the side of those regimes out of some commitment to something called “communism.” Again, I make no bones about the fact that I find “The Communist Manifesto” to be an inspirational text, but even if you are purely and deeply critical of it, it is simply embarrassingly ignorant not to engage with the fact that there have, for over a hundred years, been debates within Marxism over exactly what the shape of political fidelity to the manifesto should look like, and indeed over the directions taken by the various regimes traceable to the Russian Revolution of 1917, in one form or another. Whatever you think of any of the various sides in any of these debates, to argue in ignorance of all those incredibly critical communist currents implacably set against the dead hand of Stalinism just won’t do.

I try to make the case in the book that inextricable from the vision in the manifesto is a grassroots democratic control of society, a democracy infinitely greater than any of the etiolated versions we’ve hitherto seen. And that the structural antipathy of actually existing socialism — to varying degrees, to be sure, and taking highly different shapes — sets it against the vision of the manifesto. I try to at least advert to the specific historical circumstances that I think gave rise to this tragedy. And, to repeat myself, to have a good-faith debate about whether or not my analysis is correct is one thing, and I welcome it, including with those profoundly opposed to my position. But simply to gesture vaguely at Stalinism and say that it disproves the manifesto is just intellectually embarrassing and, again, incurious.

Be that as it may, Marx’s vision of a future social and economic order beyond capitalism has come under criticism by ecological economists because it is supposedly driven by technological determinism and human domination over nature. In sum, Marx’s vision of communism as a form of human development is deemed unsustainable in the eyes of those who embrace the “degrowth” perspective due to its treatment of natural conditions as effectively unlimited. Personally, I find this criticism quite puzzling since both Marx and Engels treated humans and nature as “not separate things” and even defined communism as the “unity of being of man with nature.” Do you agree with those who view “The Communist Manifesto” as embracing an essentially anti-ecological view?

This is one of those instances in which I take a position somewhat analogous to Victor Serge’s position with regard to the Bolsheviks and Stalinism (to echo your previous question). He said: “It is often said that ‘the germ of all Stalinism was in Bolshevism at its beginning.’ Well, I have no objection. Only, Bolshevism also contained many other germs, a mass of other germs, and those who lived through the enthusiasm of the first years of the first victorious socialist revolution ought not to forget it. To judge the living man by the death germs which the autopsy reveals in the corpse — and which he may have carried in him since his birth — is that very sensible?”

I agree with you, in that a rigorous analysis of Marx’s and Engels’s position does indeed stress their view of the false distinction between nature and humanity, and to that extent you could even say nature and society. I think there is much fertile ground for an ecologically conscious democratic communism in notions such as the fulfillment of “species-being,” and in Marx’s conception of the “irreparable rift in the interdependent process of social metabolism” under capitalism, that John Bellamy Foster calls the “metabolic rift,” and the ecological catastrophe concomitant on it. All of which said, I think there are also germs of a somewhat less nuanced Prometheanism in the manifesto. (I’m not at all averse to a Prometheanism worthy of the name, but many tendencies so-glossed lean toward a kind of vulgar productivism.) The manifesto’s visions of a post-scarcity classless society are bracing and inspiring and convincing to me. But they can be — not must be, but can be and have been — interpreted in ways that, from my perspective, are predicated on a vaguely utopian position about the social good of “human ingenuity” nebulously inextricable from productivism, as manifested in what is sometimes called ecomodernism (though I wish it were another label).

This is an argument that I and my comrades in the Salvage Collective engaged with in our short book The Tragedy of the Worker, and the perspective therein informs this book on the manifesto. Relatedly, I think any thinking inspired by the manifesto that understates the task of repair and salvage necessary in any post-capitalist world, given the ecological depredations of capitalism and the dynamics of ecological crisis already in place, is not being realistic. What that doesn’t mean is either the stasis of despair — I think despair gets a bad rap, but I’m pro what John Berger called “undefeated despair” rather than surrender — or a belief in the necessity of some ascetic communism, against which the manifesto explicitly set itself. And I think it was right to do so, on ethical and analytical grounds.

One of the few positive things about the recent years is that a sense of the pressing nature of ecological catastrophe is clear and present, and embedding into radical theory in a very positive way. So, to return to your question: No, I certainly don’t think “The Communist Manifesto” is intrinsically ecologically vulgar or worse. But nor do I think that, in this epoch, we can do without posing such questions explicitly as part of a radical left agenda, and mindful that the work of repair capitalism will bequeath us will be enormous.

Conversely, I should add, I think any attempt to forge an ecological politics that is not predicated on an analysis that capitalism’s prioritization of profit over need, and the urgent human necessity of moving beyond capitalism, to a true democracy of grassroots control, is on a hiding to nothing.

Source: https://truthout.org/

C.J. Polychroniou is a political scientist/political economist, author, and journalist who has taught and worked in numerous universities and research centers in Europe and the United States. Currently, his main research interests are in U.S. politics and the political economy of the United States, European economic integration, globalization, climate change and environmental economics, and the deconstruction of neoliberalism’s politico-economic project. He is a regular contributor to Truthout as well as a member of Truthout’s Public Intellectual Project. He has published scores of books and over 1,000 articles which have appeared in a variety of journals, magazines, newspapers and popular news websites. Many of his publications have been translated into a multitude of different languages, including Arabic, Chinese, Croatian, Dutch, French, German, Greek, Italian, Japanese, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish and Turkish. His latest books are Optimism Over Despair: Noam Chomsky On Capitalism, Empire, and Social Change (2017); Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (with Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin as primary authors, 2020); The Precipice: Neoliberalism, the Pandemic, and the Urgent Need for Radical Change (an anthology of interviews with Noam Chomsky, 2021); and Economics and the Left: Interviews with Progressive Economists (2021).

A Criminal Attack On Democracy: Why Brazil’s Fascists Should Not Get Amnesty

From all the excited cries echoing from the red tide that took over Brasília during Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s (known as Lula) inauguration as the Brazilian President on January 1, 2023, the most significant—and challenging, especially from the institutional stance of the new government—was the call for “no amnesty!” The crowds chanting those words were referring to the crimes perpetrated by the military dictatorship in Brazil from 1964 to 1985 that still remain unpunished. Lula paused his speech, to let the voices be heard, and followed up with a strong but restrained message about accountability.

Lula’s restraint shows his respect for the civic limitation of the executive, standing in sharp contrast to former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro’s notion of statesmanship. After all, one of the characteristics that allow us to properly qualify “Bolsonarismo” as fascism is the deliberate amalgamation between the institutional exercise of power and counter-institutional militancy. As a president, Bolsonaro went beyond mixing those roles; he occupied the state in constant opposition against the state itself. He constantly attributed his ineptitude as a leader to the restrictions imposed by the democratic institutions of the republic.

While Bolsonaro projected an image of being a strongman in front of cameras, which eventually helped him climb the ladder of power, he maintained a low profile in Congress and his three-decade-long congressional tenure is a testament to his political and administrative irrelevance. His weak exercise of power revealed his inadequacy as a leader when he finally took over as president. Bolsonaro catapulted to notoriety when he cast his vote for impeaching former President Dilma Rousseff in 2016.

Before casting his vote, Bolsonaro took that opportunity to pay homage to Colonel Carlos Alberto Brilhante Ustra, “convicted of torture” during the military dictatorship, whom he jestingly referred to as “the dread of Dilma Rousseff!”; Ustra was responsible for systematically torturing the former head of state when she, then a young Marxist guerrilla, was jailed by the dictatorship. From that day until Bolsonaro’s last public appearance—after which he fled the country to make his way to Orlando, Florida before Lula’s inauguration—the only opportunity he ever had to stage his electoral persona was by instigating his supporters through incendiary speeches. That combination led to an impotent government, run by someone who encouraged his supporters to cheer for him using the ridiculously macho nickname “Imbrochável,” which translates to “unfloppable.”

By endorsing the need for accountability while respecting the solemnity of the presidency and allowing people to call for “no amnesty,” Lula restores some normality to the dichotomy that exists between the representative/represented within the framework of a liberal bourgeois democracy. A small gesture, but one that will help establish the necessary institutional trust for fascism to be scrutinized. Now, the ball is in the court of the organized left; the urgency and radicality of the accountability depend on its ability to theoretically and politically consubstantiate the slogan “no amnesty.”

No amnesty for whom? And for what? What kind of justice should be served to the enemies of the working class? To the former health minister who, claiming to be an expert in logistics, turned Manaus, the capital city of Amazonas into a “herd immunity test laboratory” to deal with a collapsing health care system during the peak of the COVID outbreak in Brazil; To the former environment minister who sanctioned the brutal colonization of Indigenous lands by changing environmental legislation; To a government who supported expanding civilian access to army-level weaponry; To the national gun manufacturer who endorsed such political aberration and promoted weapons sale; To the health insurance company that conducted unconsented drug tests on elderly citizens, while espousing to the motto, “death is a form of discharge”; To Bolsonaro himself, who among so many crimes, decided to repeatedly deny science and advertise hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as cures to COVID-19; To the chancellor who used the Itamaraty (Brazil’s equivalent of the U.S. State Department) to intentionally marginalize Brazil in the international community; To the media owners who endorsed or tolerated all that misanthropy, whitewashing fascist rhetoric, and offered a megaphone for amplifying racism, sexism, LGBT phobia, and, underlying them all, the brutal classicism.

The list goes on. There are so many crimes, so many delinquent individuals and corporations, and so many victims—starting with the deaths of innocent people because of COVID and the trauma suffered by their families and spreading to all vulnerable populations: Indigenous people, the Black population, Maroons, and LGBTQIA+—that a dedicated agency to investigate and prosecute them all is necessary. Perhaps the substance we must inject into the cry for “no amnesty” is the establishment of a special court. As suggested by professor Lincoln Secco, that should be the Manaus Tribunal, named after the city that was used as a testing ground for Bolsonaro’s anti-vax propaganda, where patients were left to die at the height of the COVID pandemic. And hopefully, the Manaus Tribunal, observing all the rites, all the civility, and all the legal requirements will be capable of bringing about the historic outcome the Constitutional Assembly of 1988 fell short of delivering: close the doors of Brazilian institutions to fascism, forever.

Author Bio:

This article was produced by Globetrotter.

Gabriel Rocha Gaspar is a Marxist Brazilian activist and journalist, with a master’s degree in literature from the Sorbonne Nouvelle Paris 3 University. For five years, he was a reporter at the French public radio RFI, while also working as a foreign affairs correspondent for several Brazilian media outlets. Currently, he is a columnist at Mídia Ninja.

Source:Globetrotter

Paul Bischoff – Internet Censorship 2023: A Global Map Of Internet Restrictions

More than 60 percent of the world’s population (5.03 billion people) uses the internet.

More than 60 percent of the world’s population (5.03 billion people) uses the internet.

It’s our source of instant information, entertainment, news, and social interactions.

But where in the world can citizens enjoy equal and open internet access – if anywhere?

In this exploratory study, our researchers have conducted a country-by-country comparison to see which countries impose the harshest internet restrictions and where citizens can enjoy the most online freedom. This includes restrictions or bans for torrenting, pornography, social media, and VPNs. Also whether there are restrictions or heavy censorship of political media and any additional restrictions for messaging/VoIP apps.

Although the usual culprits take the top spots, a few seemingly free countries rank surprisingly high. With ongoing restrictions and pending laws, our online freedom is at more risk than ever.

We scored each country on six criteria. Each of these is worth two points aside from messaging/VoIP apps which is worth one (this is due to many countries banning or restricting certain apps but allowing ones run by the government/telecoms providers within the country). The country receives one point if the content—torrents, pornography, news media, social media, VPNs, messaging/VoIP apps—is restricted but accessible, and two points if it is banned entirely. The higher the score, the more censorship.

Source: https://www.comparitech.com/blog/vpn-privacy/internet-censorship-map/

Follow: https://www.comparitech.com/

Also follow: https://freedomhouse.org/

The Brazilian Hard Right Are Already A Political Cliché

On January 8, 2023, large crowds of people—dressed in colors of the Brazilian flag—descended on the country’s capital, Brasília. They invaded the federal building and Supreme Court and vandalized public property. This attack by the rioters had been widely expected since the invaders had been planning “weekend demonstrations” for days on social media.

On January 1, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (known as Lula) was formally sworn in as Brazil’s president, but during his inauguration there was no such melee. It was as if the vandals were waiting until the city was quiet and when Lula himself was out of town. For all the braggadocio of the attack, it was an act of extreme cowardice.

The man whom Lula defeated—former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro—was nowhere near Brasília. He was not even in Brazil. He fled before the inauguration—to escape prosecution, presumably—to Orlando, Florida, in the United States. But even if Bolsonaro was not in Brasília, Bolsonaristas—as his supporters are known—were everywhere in evidence. Before Bolsonaro lost the election to Lula on October 30, 2022, Le Monde Diplomatique Brasil suggested that Brazil was going to see “Bolsonarism without Bolsonaro.” The political party with the largest bloc in the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate in Brazil is the far-right Liberal Party, which served as the political vehicle of Bolsonaro during his presidency. The toxic right-wing stain remains both in the elected bodies and on social media.

The two men responsible for public safety in Brasília—Anderson Torres, secretary of public security of the federal district, and Ibaneis Rocha, governor of the federal district—are close to Bolsonaro. Torres was a minister in Bolsonaro’s government and was on holiday in Orlando during the attack; Rocha took the afternoon off, a sign that he did not want to be at his desk during the attack. For their complicity in the attack, Torres was dismissed from his post, and Rocha has been suspended. The federal government has taken charge of security, and thousands of “fanatic Nazis,” as Lula called them, have been arrested.

The slogans and signs that pervaded Brasília were less about Bolsonaro and more about the hatred felt for Lula, and the potential of his pro-people government. Big business—mainly agribusiness—sectors are furious about the reforms proposed by Lula. This attack was partly the result of the built-up frustration felt by people who have been led to believe that Lula is a criminal—which the courts have shown is false—and partly is a warning from Brazil’s elites. The ragtag nature of the attack resembles the January 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol by supporters of former U.S. President Donald Trump. The illusions about the dangers of a communist U.S. President Joe Biden or a communist Lula seem to have masked the animosity of the elites to even the mildest rollback of neoliberal austerity.

Author Bio:

This article was produced by Globetrotter.

Vijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor, and journalist. He is a writing fellow and chief correspondent at Globetrotter. He is an editor of LeftWord Books and the director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. He is a senior non-resident fellow at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China. He has written more than 20 books, including The Darker Nations and The Poorer Nations. His latest books are Struggle Makes Us Human: Learning from Movements for Socialism and (with Noam Chomsky) The Withdrawal: Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan, and the Fragility of U.S. Power

Source: Globetrotter

Why The Climate Justice March In South Korea Could Be A Game Changer For The Environment

On September 24, 2022, more than 30,000 people occupied the main roads of downtown Seoul, South Korea, for the nation’s largest climate justice march. The sheer turnout of people from all walks of life and the participation by a wide range of advocacy groups were a testament to the impact of climate change on every aspect of life: human rights, women’s rights, religion, food insecurity, and labor rights. For many of these advocacy movements in Seoul, recent crises like COVID-19 have brought home the urgent need to address the climate crisis.

Opening with a rally in Namdaemun Plaza at 3 p.m., the two-hour march occupied four out of six lanes of Seoul’s main Sejong-daero Boulevard. Standing on moving flatbed trucks, people spoke about the intersectionality of the climate crisis and other issues, including labor insecurity, housing instability, and social discrimination.

Ten megaphone-mounted flatbed trucks placed at regular intervals logistically ushered large crowds of protesters—brightly clad youth in headdresses in sunflower or coral reef shapes, families wrapped in “Carbon Neutral” cloak-like banners, Buddhist monks with globe-painted temple lanterns, Catholic nuns wearing “Save the Earth” tunics and holding “Anti-nuclear NOW” placards, regional community groups demanding a stop to coal plants and new airports, and countless union members in matching vests, flying union banners.

The groups of protesters regularly chanted in unison: “lives over profit” and “we can’t live like this anymore!” Drumming, music, and dance filled the streets. During a five-minute “die-in,” protesters fell to the ground, front to rear, like cascading dominoes.

The march was the result of three months of planning, promotion, and fundraising by Action for Climate Justice, a coalition of more than 400 civic, regional/community, and trade union movements united under the guiding concept of climate justice.

Like previous marches, environmental NGOs played leading roles in the organizing, such as Green Korea United and the Korean Federation for Environmental Movements (KFEM), alongside youth movements. But 2022 also saw a large influx of long-established and new movement groups not exclusive to environmental activism but for whom the climate crisis has become central to their agenda—human rights groups, women’s groups, social movements, political parties, religious networks, food cooperatives, irregular contract workers, and trade union movements.

From the Human Rights Movement Sarangbang, combating the violence of political and economic discrimination and exploitation since 1993, to the recent Human Rights Movement Network Baram working to secure the rights and dignity of discriminated groups, such as women, the disabled, LGBTQ communities, immigrants, and irregular contract workers—the COVID-19 pandemic has brought the climate crisis to the fore of their activities.

Climate policy has likewise become a pressing issue for the Anti-Poverty Alliance, which emerged during mass layoffs and bankruptcies following the 1997 financial crisis and neoliberalization of the Korean economy. This “IMF era” alliance has grown to include 49 member organizations engaged in various struggles for livelihood, from the fight for a universal basic income to alternatives to substandard housing (including polytunnel villages where people live in greenhouse-like shelters made out of vinyl) and housing instability in the face of Korea’s speculative housing markets and climate change.

Religious orders are also a sizable part of the movement now. Building on their legacy of sheltering democracy movement activists in the 1970s and 1980s, Korea’s faith-based groups have been organizing a climate movement that is cross-denominational and transnational such as the pan-Asian Inter-Religious Climate and Ecology Network.

The large outpouring of protesters in September 2022 even surpassed organizers’ expectations. Over the past two years, pandemic restrictions on gatherings and suspension of protest permits in South Korea have brought activism online and into classrooms and have included the unconventional occupation of public spaces. Some of the most visible climate actions in Seoul in 2021 appeared not on the city streets but rather above and underneath them, on large billboards mounted on skyscrapers and LCD screens installed inside subway lines. The yearlong campaign from 2020 to 2021, Climate Citizens 3.5, which was jointly conducted with artists, environmental groups, and researchers, used a chunk of its total budget, the largest allotted by Arts Council Korea, to rent 30 large-scale outdoor electronic billboards, 219 digital screens inside 21 subway stations, and all of the advertising space in 48 subway cars. Spread across the city, the billboards and displays were tailored to convey climate change-focused messages targeted to each location—climate policy changes for the traffic-heavy city center at Gwanghwamun and consumption-related taglines for shopping districts in Myeongdong and Gangnam: “Spend Less, Live More!”

Such overlapping and expanding networks in the climate justice coalition attest to the burgeoning consciousness of the climate crisis for a population whose Cold War-divided peninsula placed North Korea and South Korea in the shadow of a nuclear winter long before the threat of exterminism via global warming became an issue. As policy researcher and activist of the Climate Justice Alliance Han Jegak states, “while climate change denial is not a widespread problem in South Korea as it is in other countries, there is still a generalized denial about the urgency to act, the attitude is that we can follow what other countries are doing.” He adds, “people express fear and depression over climate change, but such feelings do not lead to proactive actions. We need to forge alternatives collectively in place of mostly individualized actions like hyper-recycling. The movement needs to harness the anger related to the climate crisis and mobilize that.” One such concrete outcome from the march was the exponential rise in signatories successfully introducing a civil memorandum to stop the opening of new coal plants to the National Assembly floor.

For many in the movement, the unprecedented rainstorms and flooding that took the lives of several people including a family in a semi-basement flat in Seoul in August 2022 has inflamed the call to action. For the Korean Confederation of Trade Unions (KCTU), this incident came as a personal loss, as one of the deceased was a union activist. The largest independent democratic trade union association in Korea with 1.1 million members, KCTU formalized its participation in climate action networks when it voted in a special committee on climate justice within its organization in February 2021. Environmental groups have long reached out to KCTU for more active participation in the movement as “public and energy sector unions and irregular contract workers are situated at the forefront of struggles over policy changes as well as facing the brunt of its effects,” as emphasized by KFEM activist and member of the climate coalition Kwon Woohyun. In many ways, the union’s participation in the climate movement was a significant development, explains Kim Seok, KCTU policy director, because “it was a decision to make the climate issue a key component of KCTU policies, including the collective bargaining agreement process, which is the most fundamental activity for unions.” In 2022, KCTU members circulated the most posters and mobilized 5,000 union activists to join the climate march.

For a country whose export economy is centered on energy-intensive industries, environmental activism by labor unions faces complicated challenges. KCTU must contend with internal pressure from rank-and-file workers seeking compensation for job losses from the transition to clean energy as well as the broader national context in which the state has relinquished the development of clean energy industries to profit-seeking private sector companies.

In the face of these challenges, KCTU’s proactive participation in the Action for Climate Justice coalition and its actions to work jointly with wide-ranging environmental and social movements hold the promise of broadening and solidifying the foundations of the climate movement going forward, while signaling the beginning of a potentially powerful new form of climate activism taking shape in South Korea.

Author Bio:

This article was produced by Globetrotter.

Alice S. Kim received her PhD from the Rhetoric Department at UC Berkeley and is a writer, researcher, and translator living in Seoul. Her publications include “The ‘Vietnamese’ Skirt and Other Wartime Myths” in The Vietnam War in the Pacific World (UNC Press, 2022) and “Left Out: People’s Solidarity for Social Progress and the Evolution of Minjung After Authoritarianism,” in South Korean Social Movements (Routledge, 2011).

Source: Globetrotter

A Progressive Political Economy Guide To Inflation

Mainstream economics failed miserably in addressing the financial crisis of 2007-08, so why would it be any different now when it comes to making sense of the rising inflation of the past 18 months?

Mainstream economics failed miserably in addressing the financial crisis of 2007-08, so why would it be any different now when it comes to making sense of the rising inflation of the past 18 months?

Since 2021, prices have surged dramatically across countries and inflation has become a global challenge.

Global central banks delivered historic rate hikes in 2022 in order to tame inflation and continued doing so even when inflation was falling, thereby risking a global recession.

Indeed, for the past five months, average inflation in the U.S. has been at 2.4%. Across Europe, inflation has also been dropping. In Spain, for instance, consumer prices rose 5.8% in December, down from 6.8% in the previous month. The December figure represented the fifth consecutive month of declining inflation in Spain. Yet, the European Central Bank—which like the U.S. Federal Reserve has also set the target rate for inflation at the arbitrary number of 2% per year—plans to continue raising interest rates “significantly further” as it deems that inflation “remains far too high and is projected to stay above the target for too long.”

Meanwhile, both the U.S. and European economies are expected to enter a recession in 2023. For what it’s worth, the head of the IMF expects a full one-third of the world to slide into recession this year.

What has been causing the upward trends in inflation and why do central banks around the world keep raising interest rates, a policy which will slow economic growth and result in lower wage increases and fewer jobs? Several factors are at play in causing a surge in prices, which include the Covid-19 pandemic, geopolitics, and corporate mark-ups and profit margins, while pure capitalist logic and interests explain why central banks are raising interest rates to fight inflation.

These were some of the conclusions reached by the progressive economists who participated in an international conference on “Global Inflation Today” organized by the renowned Political Economy Research Institute (PERI) at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and held from December 2-3, 2022.

To start with, a co-authored paper by Robert Pollin (Distinguished Professor of Economics and Co-Director of PERI at UMass Amherst) and Hanae Bouazza shows convincingly that there is no justification why the Federal Reserve and other central banks aim for an inflation target of 2%. Indeed, their research finds “no consistent evidence supporting the conclusion that economies at any income level will achieve significant GDP benefit when they maintain inflation within low single digits, i.e., between the 0 – 2.5 percent inflation range.” Not only that, but the “evidence… suggests that, in general, economies are more likely to achieve higher GDP growth rates in association with inflation ranges in the range of 2.5 – 5 percent, 5 – 10 percent and, for the most part, 10 – 15 percent.”

These are significant findings which raise serious questions about the goals of macro policy. Indeed, if inflation-targeting policy is not conducive to promoting economic growth, what is its primary aim? Citing the work of scholars who have done extensive research around this question, such as Gerald Epstein (Professor of Economics and Co-Director of PERI at UMass Amherst) and others, Pollin and Bouazza suggest that corporate profitability is the primary aim of inflation-targeting policy. “Protecting the wealth of the wealthy” is the reason why the Fed has taken aggressive steps to tame inflation by raising interest rates, Epstein pointed out in a recent joint interview with Pollin.

With regard to the actual causes of inflation in 2021-22, a paper co-authored by Asha Banerjee and Josh Bivens of the Economic Policy Institute identifies the Covid-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine as key factors in the inflationary surge of the past 18 months or so but argues that profit mark-ups added immensely to inflationary pressures over the same period. Of equal importance here is that the authors present more than sufficient evidence to counter the mainstream economic perspective that lays the blame for the rise of inflation in the U.S. on the American Rescue Plan. Indeed, the data they present, on both the domestic and international fronts, does not support the claim that too much fiscal spending overheated the economies, fueling runaway inflation.

Another paper presented at the PERI conference, co-authored by C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh, on how low-and middle-income countries can respond to inflation, also argues that there are more important factors than the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine behind the current inflation crisis. The sharp rise in global prices of food and fuel, Chandrasekhar and Ghosh contend, was driven by “profiteering, price expectations, and associated speculation.” They show, for instance, that while there were sharp spikes in the prices of food and fuel between February and July 2022, “the supplies of oil and gas to Europe remained largely unaffected.”

The analyses on inflation and its causes, as well as the actual aims of inflation-targeting policy, made by all of the presenters at the PERI conference (which included many leading progressive economists such as William Spriggs, Gerald Epstein, Thomas Ferguson, Nancy Folbre, James K. Galbraith, Servaas Storm, and Isabella Weber, among others) can be described as a Progressive Political Economy Guide to Inflation. Indeed, they show how powerful heterodox economic approaches are in disclosing the real forces driving inflation and the actual reasons for central banks raising sharply interest rates. And, by extension, they also reveal the flaws and limitations of mainstream economics, which is in dire need of a major overhaul.

Source: https://www.commondreams.org

C.J. Polychroniou is a political economist/political scientist who has taught and worked in numerous universities and research centers in Europe and the United States. His latest books are The Precipice: Neoliberalism, the Pandemic and the Urgent Need for Social Change (A collection of interviews with Noam Chomsky; Haymarket Books, 2021), and Economics and the Left: Interviews with Progressive Economists (Verso, 2021).