Elon Musk Plans To Profit From Twitter, Not Create A Town Square For Global Democracy

The world’s richest man has bought one of the world’s most popular social media platforms. Elon Musk, CEO of Tesla, is currently worth about $210 billion, and in November 2021 he was worth nearly $300 billion—an unheard-of figure for any individual in human history. Not only does his wealth bode ill for democracy, considering the financial influence that he has over politics, but his acquisition of Twitter, a powerful opinion platform, as a private company also further cements his power.

To put his money into perspective, if Musk wanted to gift every single Twitter user $800, (given that Twitter has about 238 million regular users) he would still have about $20 billion left over to play with and never ever want for money. Musk’s greed is the central fact to keep in mind when attempting to predict what his ownership of Twitter means.

Musk has shrewdly fostered a reputation for being a genius, deserving of his obscene wealth. But his private texts during Twitter deal negotiations, recently revealed in court documents during legal wrangling over the sale, paint a picture of a simple mind unable to come to terms with his excess. His idea of “fun” is having “huge amounts of money” to play with.

And, he has an outsized opinion of himself. Billionaires like Musk see themselves as being the only ones capable of unleashing greatness in the world. He said as much in his letter to the Twitter board saying, “Twitter has extraordinary potential,” and adding, “I will unlock it.” Such hubris is only natural when one wields more financial power than the human brain is capable of coming to terms with.

Musk has also been adept at cultivating a reputation for having a purist approach to free speech, and diverting attention away from his wealth. Former president Donald Trump, who repeatedly violated Twitter’s standards before eventually being banned, said he’s “very happy that Twitter is now in sane hands.” Indeed, there is rampant speculation that Musk will reinstate Trump’s account.

But, Nora Benavidez, senior counsel and director of Digital Justice and Civil Rights at Free Press, said in an interview earlier this year that Musk is not as much of a free speech absolutist as he is “kind of an anything-goes-for-Twitter future CEO.”

She adds, “I think that vision is one in which he imagines social media moderation of content will just happen. But it doesn’t just happen by magic alone. It must have guardrails.”

The guardrails that Twitter has had so far did not work well enough. It took the company four years of Trump’s violent and inciteful tweets, and a full-scale attack on the U.S. Capitol, to finally ban him from the platform. In the week after Trump and several of his allies were banned, misinformation dropped by a whopping 73 percent on the platform.

Twitter delayed action on Trump’s tweets only because its prime goal is to generate profits, not foster free speech. These are Musk’s goals too, and all indications suggest he will weaken protections, not strengthen them.

According to Benavidez, “His imagined future that Twitter will somehow be an open and accepting square—that has to happen very carefully through a number of things that will increase better moderation and enforcement on the company’s service.” Musk appears utterly incapable of thinking about such things.

Instead, his plans include ideas like charging users $20 a month to have a verification badge next to their names—a clear nod to his worldview that money ought to determine what is true or who holds power.

Benavidez explains that “because it has helped their bottom lines,” companies like Twitter are “fueling and fanning the flames for the most incendiary content,” such as tweets by former Twitter user Trump and his ilk, incitements to violence, and the promotion of conspiracy theories.

There is much at stake given that Twitter has a strong influence on political discourse. For example, Black Twitter, one of the most important phenomena to emerge from social media, is a loosely organized community of thousands of vocal Black commentators who use the platform to issue powerful and pithy opinions on social and racial justice, pop culture, electoral politics, and more. Black Twitter played a critical role in helping organize and spreading news about protests during the 2020 uprising sparked by George Floyd’s murder at the hands of Minneapolis police.

But within days of Musk’s purchase of Twitter, thousands of anonymous accounts began bombarding feeds with racist content, tossing around the N-word, leaving members of Black Twitter aghast and traumatized. Yoel Roth, the company’s head of safety and integrity—who apparently still retains his job—tweeted that “More than 50,000 Tweets repeatedly using a particular slur came from just 300 accounts,” suggesting this was an organized and coordinated attack.

Whether or not Musk’s buyout of Twitter will actually succeed in making history’s richest man even richer by rolling out the welcome mat to racist trolls is not clear. Already, numerous celebrities with large followings have closed their Twitter accounts. Hollywood’s top Black TV showrunner, Shonda Rhimes posted her last tweet, saying, “Not hanging around for whatever Elon has planned. Bye.”

Twitter also impacts journalism. According to a Pew Research study, 94 percent of all journalists in the U.S. use Twitter in their job. Younger journalists favor it the most of all age groups. Journalists covering the automotive industry are worried about whether criticism of Tesla will be tolerated on the platform. And, Reporters Without Borders warned Musk that “Journalism must not be a collateral victim” of his management.

Misinformation and distrust in government lead to apathy and a weakening of democracy. This is good for billionaires like Musk, who has made very clear that he vehemently opposes a wealth tax of the sort that Democrats are backing. Indeed, he has used his untaxed wealth to help buy the platform. If Twitter is capable of influencing public opinion in order to help elect anti-tax politicians, why wouldn’t Musk pursue such a strategy?

Musk has made it clear that he will not be a hands-off owner. He set to work as soon as the deal was cemented by firing Twitter’s top executives and the entire board. As a privately owned company, Twitter will now answer to Musk and his underlings, not to shareholders.

Benavidez summarizes one of the most important lessons that Musk’s purchase offers: “It can’t simply be that this company or that company is owned and at the whim of a single individual who might be bored and want to take on a side project.”

This article was produced by Economy for All, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

Sonali Kolhatkar is an award-winning multimedia journalist. She is the founder, host, and executive producer of “Rising Up With Sonali,” a weekly television and radio show that airs on Free Speech TV and Pacifica stations. Her forthcoming book is Rising Up: The Power of Narrative in Pursuing Racial Justice (City Lights Books, 2023). She is a writing fellow for the Economy for All project at the Independent Media Institute and the racial justice and civil liberties editor at Yes! Magazine. She serves as the co-director of the nonprofit solidarity organization the Afghan Women’s Mission and is a co-author of Bleeding Afghanistan. She also sits on the board of directors of Justice Action Center, an immigrant rights organization.

Offloading Climate Responsibility On The Victims Of Climate Change

In this interview, Nnimmo Bassey, a Nigerian architect and award-winning environmentalist, author, and poet, talks about the history of exploitation of the African continent, the failure of the international community to recognize the climate debt owed to the Global South, and the United Nations Climate Change Conference that will take place in Egypt in November 2022.

Bassey has written (such as in his book To Cook a Continent) and spoken about the economic exploitation of nature and the oppression of people based on his firsthand experience. Although he does not often write or speak about his personal experiences, his early years were punctuated by civil war motivated in part by “a fight about oil, or who controls the oil.”

Bassey has taken square aim at the military-petroleum complex in fighting gas flaring in the Niger Delta. This dangerous undertaking cost fellow activist and poet Ken Saro-Wiwa his life in 1995.

Seeing deep connections that lead to what he calls “simple solutions” to complex problems like climate change, Bassey emphasizes the right of nature to exist in its own right and the importance of living in balance with nature, and rejects the proposal of false climate solutions that would advance exploitation and the financialization of nature that threatens our existence on a “planet that can well do without us.”

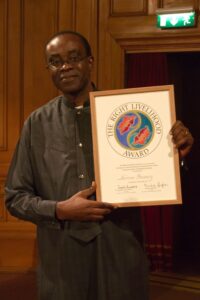

Bassey chaired Friends of the Earth International from 2008 through 2012 and was executive director of Environmental Rights Action for two decades. He was a co-recipient of the 2010 Right Livelihood Award, the recipient of the 2012 Rafto Prize, a human rights award, and in 2009, was named one of Time magazine’s Heroes of the Environment. Bassey is the director of Health of Mother Earth Foundation, an ecological think tank, and a board member of Global Justice Ecology Project.

Steve Taylor: Climate change is a complex problem, but maybe there’s a simple solution. What might that look like?

Nnimmo Bassey: Simple solutions are avoided in today’s world because they don’t support capital. And capital is ruling the world. Life is simpler than people think. So, the complex problems we have today—they’re all man-made, human-made by our love of complexities. But the idea of capital accumulation has led to massive losses and massive destruction and has led the world to the brink. The simple solution that we need, if we’re talking about warming, is this: Leave the carbon in the ground, leave the oil in the soil, [and] leave the coal in the hole. Simple as that. When people leave the fossils in the ground, they are seen as anti-progress and anti-development, whereas these are the real climate champions: People like the Ogoni people in the Niger Delta, the territory where Ken Saro-Wiwa was murdered by the Nigerian state in 1995. Now the Ogoni people have kept the oil in their territory in the ground since 1993. That is millions upon millions of tons of carbon locked up in the ground. That is climate action. That is real carbon sequestration.

ST: Could you talk about the climate debt that is owed to the Global South in general, and African nations in particular?

NB: There’s no doubt that there is climate debt, and indeed an ecological debt owed to the Global South, and Africa in particular. It has become clear that the sort of exploitation and consumption that has gone on over the years has become a big problem, not just for the regions that were exploited, but for the entire world. The argument we’re hearing is that if the financial value is not placed on nature, nobody’s going to respect or protect nature. Now, why was no financial cost placed on the territories that were damaged? Why were they exploited and sacrificed without any consideration or thought about what the value is to those who live in the territory, and those who use those resources? So, if we’re to go the full way with this argument of putting price tags on nature so that nature can be respected, then you have to also look at the historical harm and damage that’s been done, place a price tag on it, recognize that this is a debt that is owed, and have it paid.

ST: You’ve discussed in our interview how some policies meant to address climate change are “false solutions,” particularly those intended to address the climate debt owed to the Global South and to Africa in particular. Could you talk a bit about the misnomer of the Global North’s proposals of so-called “nature-based solutions” to the climate crisis that claim to emulate the practices and wisdom of Indigenous communities in ecological stewardship, but which actually seem like an extension of colonial exploitation—rationalizations to allow the richer nations that are responsible for the pollution to continue polluting.

NB: The narrative has been so cleverly constructed that when you hear, for example, reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD), everybody says, “Yes, we want to do that.” And now we’re heading to “nature-based solutions.” Who doesn’t want nature-based solutions? Nature provided the solution to the challenges [that Indigenous people have] had for centuries, for millennia. And now, some clever people appropriate the terminology. So that by the time Indigenous communities say they want nature-based solutions, the clever people will say, “well, that’s what we’re talking about.” Whereas they’re not talking about that at all. Everything’s about generating value chains and revenue, completely forgetting about who we are as part of nature. So, the entire scheme has been one insult after another. The very idea of putting a price on the services of Mother Earth, and appropriating financial capital from those resources, from this process, is another horrible way by which people are being exploited.

ST: How does REDD adversely impact local communities on the African continent?

NB: REDD is a great idea, which should be supported by everyone merely looking at that label. But the devil is in the detail. It is made by securing or appropriating or grabbing some forest territory, and then declaring that to be a REDD forest. And now once that is done, what becomes paramount is that it is no longer a forest of trees. It is now a forest of carbon, a carbon sink. So, if you look at the trees, you don’t see them as ecosystems. You don’t see them as living communities. You see them as carbon stock. And that immediately sets a different kind of relationship between those who are living in the forest, those who need the forest, and those who are now the owners of the forest. And so, it’s because of that logic that [some] communities in Africa have lost access to their forests, or lost access to the use of their forests, the way they’d been using [them] for centuries.

ST: As an activist, you have done some dangerous work opposing gas flaring. Could you tell us about gas flaring and how it impacts the Niger Delta?

NB: Gas flaring, simply put, is setting gas on fire in the oil fields. Because when crude oil is extracted in some locations, it could come out of the ground with natural gas and with water, and other chemicals. The gas that comes out of the well with the oil can be easily reinjected into the well. And that is almost like carbon capture and storage. It goes into the well and also helps to push out more oil from the well. So you have more carbon released into the atmosphere. Secondly, the gas can be collected and utilized for industrial purposes or for cooking, or processed for liquefied natural gas. Or the gas could just be set on fire. And that’s what we have, at many points—probably over 120 locations in the Niger Delta. So you have these giant furnaces. They pump a terrible cocktail of dangerous elements into the atmosphere, sometimes in the middle of where communities [reside], and sometimes horizontally, not [with] vertical stacks. So you have birth defects, [and] all kinds of diseases imaginable, caused by gas flaring. It also reduces agricultural productivity, up to one kilometer from the location of the furnace.

ST: The UN climate conference COP27 is coming up in Egypt. Is there any hope for some real change here?

NB: The only hope I see with the COP is the hope of what people can do outside the COP. The mobilizations that the COPs generate in meetings across the world—people talking about climate change, people taking real action, and Indigenous groups organizing and choosing different methods of agriculture that help cool the planet. People just doing what they can—that to me is what holds hope. The COP itself is a rigged process that works in a very colonial manner, offloading climate responsibility on the victims of climate change.

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited for clarity and length from the author’s conversation with Nnimmo Bassey on October 7, 2022. For access to the full interview’s audio and transcript, you can stream this episode on Breaking Green’s website or wherever you get your podcasts. Breaking Green is produced by Global Justice Ecology Project.

Guinea’s Plight Lays Bare The Greed Of Foreign Mining Companies In The Sahel

On October 20, 2022, in Guinea, a protest organized by the National Front for the Defense of the Constitution (FNDC) took place. The protesters demanded the ruling military government (the National Committee of Reconciliation and Development, or CNRD) release political detainees and sought to establish a framework for a return to civilian rule. They were met with violent security forces, and in Guinea’s capital, Conakry, at least five people were injured and three died from gunshot wounds. The main violence was in Conakry’s commune of Ratoma, one of the poorest areas in the city.

In September 2021, the CNRD, led by Colonel Mamady Doumbouya, overthrew the government of Alpha Condé, which had been in power for more than a decade and was steeped in corruption. In 2020, then-President Alpha Condé’s son—Alpha Mohamed Condé—and his minister of defense—Mohamed Diané—were accused of bribery in a complaint that the Collective for the Transition in Guinea (CTG) filed with the French National Financial Prosecutor’s Office. The complaint alleges that these men received bribes from an international consortium in exchange for bauxite mining rights near the city of Boké.

Boké, in northwestern Guinea, is the epicenter of the country’s bauxite mining. Guinea has the world’s largest reserves of bauxite (estimated to be 7.4 billion metric tons) and is the second-largest producer (after Australia) of bauxite, an essential mineral for aluminum. All the mining in Guinea is controlled by multinational firms, such as Alcoa (U.S.), China Hongqiao, and Rio Tinto Alcan (Anglo-Australian), which operate in association with Guinean state entities.

When the CNRD under Colonel Doumbouya seized power, one of the main issues at stake was control over the bauxite revenues. In April 2022, Doumbouya assembled the major mining companies and told them that by the end of May they had to provide a road map for the creation of bauxite refineries in Guinea or else exit the country. Doumbouya said, “Despite the mining boom in the bauxite sector, it is clear that the expected revenues are below expectations. We can no longer continue this fool’s game that perpetuates great inequality” between Guinea and the international companies. The deadline was extended to June, and the ultimatum’s demands to cooperate or leave are ongoing.

Doumbouya’s CNRD in Guinea, like the military governments in Burkina Faso and Mali, came to power amid popular sentiment fed up with the oligarchies in their country and with French rule. Doumbouya’s 2017 comments in Paris reflect that latter sentiment. He said that French military officers who come to Guinea “underestimate the human and intellectual capacities of Africans… They have haughty attitudes and take themselves for the colonist who knows everything, who masters everything.” This coup government—formed out of an elite force created by Alpha Condé to fight terrorism—has captured the frustrations of the population, but is unable to construct a viable agenda to exit the country’s dependence on foreign mining companies. In the meantime, the protests for a return to democracy are unlikely to be quelled.

This article was produced by Globetrotter.

How Europe Has Navigated Its Energy Crises

A multifaceted response from Europe has so far prevented its energy woes from creating widespread social and economic destabilization. But with winter approaching, the crisis is far from over and risks are getting worse.

A multifaceted response from Europe has so far prevented its energy woes from creating widespread social and economic destabilization. But with winter approaching, the crisis is far from over and risks are getting worse.

While European energy prices have eased slightly in recent months, stress continues to build across a continent that has long been dependent on access to cheap Russian energy.

Protests related to high energy costs have been held from Belgium to the Czech Republic in Europe. Fuel shortages have led to long queues to buy petrol at gas stations in France. The Don’t Pay UK movement has urged British citizens to enter a “bill strike” by refusing to pay energy bills until gas and electricity prices are reduced to an “affordable level.” Europe’s remarkably high energy prices have also fueled climate change protests across the continent.

European governments have resorted to diverse measures to manage the crisis. After the EU banned Russian coal imports, coal regulations were reduced in Poland, which has led to illegal coal mines being operated in the country. Aid packages, such as Austria’s 1.3 billion euro initiative, aim to help companies struggling with mounting energy costs. The UK “has capped the price of average household energy bills at 2,500 pounds ($2,770) a year for two years from October” and also announced a cap on energy per unit for businesses, charities, and NGOs in September.

Italy has shown considerable capability in diversifying its energy imports from Russia since the beginning of the year to reduce its dependence on the Kremlin. Under former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, Italy began to increase its reliance on Russian energy, a process that continued even after his election defeat in 2011 and Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014.

This reliance came to an abrupt end after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Italy signed natural gas deals with Egypt and Algeria in April and held additional talks with the Republic of Congo and Angola regarding energy supplies as well. In June, Italy also purchased two additional liquefied natural gas (LNG) vessels, adding to the three LNG terminals it already operates, to further diversify its natural gas (gas for short) supplies.

Not all countries, however, have matched Italy’s success of diversifying their energy imports. France declared it would cap power and gas price increases for households at 15 percent in 2023. But since more than half of France’s 56 nuclear reactors have been shut down for maintenance (Europe’s summer drought also prevented the water-based cooling systems of the French nuclear plants from functioning), France will struggle with mounting energy costs as well as upholding its traditional role as an electricity exporter to other European countries.

Like other European countries, Germany chose to nationalize some of its major energy companies, such as Uniper in September. In October, the German government proposed a 200 billion euro energy subsidies initiative. With gas storage projected to reach 95 percent capacity by November, Germany has also provided itself with significant protection.

But Germany lacks LNG infrastructure and remains vulnerable if Russia cuts off gas through pipelines completely. Currently, Germany is at level two of the country’s three-tier emergency gas plan, with the last stage introducing direct government intervention in gas distribution and rationing.

Because Germany makes the largest contributions of funds to the EU, its economic vulnerability poses concerning implications for the rest of the bloc. And in addition to suffering from gas shortages, Central European countries will “also suffer from the effects of gas rationing in the German industrial sector, given their integration into German supply chains.” Such uncertainty has blunted investment in the region, further compounding Europe’s economic issues.

These issues have underlined the perception that while Russian coal has been relatively easy to ban in Europe and Russian oil is slowly being phased out, Russian natural gas remains too important for much of the continent’s energy mix to be shunned completely.

Dozens of ships carrying LNG have been stuck off Europe’s coast, as the plants “that convert the seaborne fuel back to gas are operating at maximum limit.” High gas prices have meanwhile resulted in key industries across Europe that are reliant on the energy source to shut down, sparking fears of “uncontrolled deindustrialization.”

In addition to national strategies, European countries have pursued collective initiatives to confront the energy crisis. On September 27, Norway, Denmark, and Poland officially opened the Baltic Pipe to supply Poland with natural gas. On October 1, Greece and Bulgaria began commercial operation of the Interconnector Greece-Bulgaria (IGB) pipeline, which serves as another link in the Western-backed Southern Gas Corridor project to bring natural gas from Azerbaijan to Europe.

On October 13, France began sending Germany natural gas for the first time, based on an agreement that “Germany would generate more electricity to supply France during times of peak consumption.” The European Council stated on September 30 that EU states will implement “a voluntary overall reduction target of 10 percent of gross electricity consumption and a mandatory reduction target of 5 percent of the electricity consumption in peak hours.”

Additionally, the EU continues to debate imposing a price cap on Russian gas to the EU, and the G7 countries and its allies agreed on September 2 to implement a price cap on Russian crude oil and oil products in December 2022 and February 2023, respectively.

Germany, however, has led criticism over the “proposal to cap the price on all gas imports to the EU,” stating that the EU lacks the authority to do so, alongside expressing concerns that gas providers will simply sell gas to other countries. Norway, traditionally Europe’s second-largest gas provider after Russia, also indicated it would not accept a cap on gas, and Russia stated it would not sell oil or gas to countries doing so either. The resulting restrictions in energy supply would likely further raise prices.

European countries also remain bound by their own interests, further undermining multilateral cooperation. Croatia, for example, announced it would ban natural gas exports in September. Many European countries have criticized Germany’s planned 200 billion euro subsidies plan for fear that it “could trigger economic imbalances in the bloc.” Germany, meanwhile, declared it would not support a joint EU debt issuance on October 11, only later agreeing to the measures out of pressure from its European allies.

In September, the UK accused the EU of pushing British energy prices higher by severing energy cooperation following Brexit. The U.S. and Norway have also been singled out by EU members for profiting off the current energy crisis.

Varying levels of vulnerability have resulted in some European countries breaking with the continental norm and negotiating with Russia. Serbia, which is not in NATO or part of the EU, signed its own natural gas deal with Russia in May, while Hungary drew the ire of Western allies by signing its own gas deal with Russia in August. Hungary was among the first European countries to agree to purchase Russian natural gas in rubles, stabilizing the Russian currency as sanctions were placed on the Russian economy. If the crisis worsens considerably, other countries may follow suit.

As Europe’s energy crisis has continued, many countries across the world have become increasingly wary. European demand for LNG and a willingness to pay premiums has meant suppliers are increasingly rerouting gas to the continent.

Though rich competitors like South Korea and Japan have been able to contend with European competition for LNG, it has caused shortages elsewhere. Bangladesh and Pakistan, for example, have struggled to secure their traditional LNG imports since the beginning of the Russian invasion. Blackouts in these countries have increased, causing them to resort to more carbon-intensive energy alternatives and prompting renewed talks with Russia over LNG imports and developing pipeline networks to supply natural gas to Asia.

Europe’s decades-long exposure to Russian energy means that its current energy crisis will persist for years. Even with predictions for a relatively mild upcoming winter, overcoming this energy crisis will require cooperation and sacrifice among European states—particularly if the war in Ukraine escalates further. While the West’s solidarity will be put to the test, poorer, energy-vulnerable countries will continue to fall victim as a result of the fallout from the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

This article was produced by Globetrotter.

John P. Ruehl is an Australian-American journalist living in Washington, D.C. He is a contributing editor to Strategic Policy and a contributor to several other foreign affairs publications. He is currently finishing a book on Russia to be published in 2022.

Source: Globetrotter

Chomsky And Pollin: Pushing A Viable Climate Project Around COP27

Since the mid-1990s, the United Nations has been launching global climate summits — called COPs — which stands for Conference of the Parties. Last year was the 26th annual summit and took place in Glasgow. COP26 was supposed to be “a pivotal moment for the planet,” but the outcomes fell way short of the action needed to stop the climate crisis from becoming utterly catastrophic. This year, COP27 will be held in Egypt in the midst of an energy crisis and a war that is reshaping the global order.

Will COP27 end up as yet another failure on the part of world leaders to slow or stop global warming? Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin share their thoughts and insights on the climate crisis conundrum by dissecting the current state of affairs and what ought to be done to stop humanity’s march to the climate precipice.

Noam Chomsky is institute professor emeritus in the department of linguistics and philosophy at MIT and laureate professor of linguistics and Agnese Nelms Haury Chair in the Program in Environmental and Social Justice at the University of Arizona. One of the world’s most cited scholars in modern history and a critical public intellectual regarded by millions of people as a national and international treasure, Chomsky has published more than 150 books in linguistics, political and social thought, political economy, media studies, U.S. foreign policy and world affairs, and climate change.

Robert Pollin is distinguished professor of economics and co-director of the Political Economy Research Institute (PERI) at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. One of the world’s leading progressive economists, Pollin has published scores of books and academic articles on jobs and macroeconomics, labor markets, wages, and poverty, environmental and energy economics. He was selected by Foreign Policy Magazine as one of the “100 Leading Global Thinkers for 2013.” Chomsky and Pollin are coauthors of Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (2020).

C.J. Polychroniou: The 27th session of the Conference of the Parties (COP27) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) will take place in Egypt from November 6-18, 2022. Nearly 200 countries will come together in yet another attempt to tackle climate breakdown. COP26, held in Glasgow about the same time last year had been hailed as “our last best hope,” but it did not achieve much as too many compromises were made. The hope for COP27 is that the world will set more stringent greenhouse gas emissions reduction requirements considering the ever-clearer consequences of global warming. Noam, is this a significant climate meeting? Can we expect a breakthrough, or will it end up yet another futile international effort to reverse climate change? Indeed, what’s standing on the way of governments’ failure to slow or even reverse global warming? Isn’t the evidence already overwhelming that the world stands on a climate precipice? What prevent us from stepping back from the abyss?

Noam Chomsky: Decisions by governments tend to reflect the distribution of power in the society. As Adam Smith phrased this virtual truism in his classic work, “the masters of mankind” — in his day, the merchants and manufacturers of England — are the “principal architects” of government policy and act to ensure that their own interests will be “most peculiarly attended to” no matter how “grievous” the effects on the general welfare. Insofar as governments have failed to act in the ways that will prevent catastrophe, it is because the principal architects of policy have higher priorities.

Let’s take a look. The U.S. government has just passed a climate bill, a pale shadow of what was proposed by the Biden administration under the impact of popular climate activism, which in the end could not compete with the power of the true masters in the corporate sector. The final shadow is not meaningless. It is, however, radically insufficient in its reach, and also burdened with measures to ensure that the interests of the masters are “most peculiarly attended to.”

The bill that the masters were willing to accept includes vast government subsidies that “are already driving forward large oil and gas projects that threaten a heavy carbon footprint, with companies including ExxonMobil, Sempra and Occidental Petroleum positioned for big payouts,” the Washington Post reports. One device to satisfy the needs of the masters is “a vast wad of money” for carbon capture — a phrase that means: “Let’s keep poisoning the atmosphere freely and maybe someday someone will figure out a way to remove the poisons.”

That’s too kind. It’s much worse. “The irony of carbon capture is that the place it has proven most successful is getting more oil out of the ground. All but one major project built in the United States to date is geared toward fossil fuel companies taking the trapped carbon and injecting it into underground wells to extract crude.”

The actual cases would be comical if the consequences were not so grave. Thus “The subsidies give companies lucrative incentives to drill for gas in the most climate-unfriendly sites, where the concentration of CO2 in the fuel is especially high. The CO2, a potent greenhouse gas, is useless for making fuel, but the tax credits are awarded based on how many tons of it companies trap.”

It’s hard to believe that this is real. But it is. It’s capitalism 101 when the masters are in charge.

Other cases illustrate the same priorities. Arctic permafrost contains huge amounts of carbon and is beginning to melt as the Arctic heats much faster than the rest of the world. Scientists of one oil major, ConocoPhillips, discovered a way to slow the thawing of the permafrost. To what end? “To keep it solid enough to drill for oil, the burning of which will continue to worsen ice melt,” according to the New York Times.

The exuberant race to destruction is far more general. New fields are being opened to exploration. There is a huge expansion of oil pipelines, with “more than 24,000km of pipelines planned around world, showing ‘an almost deliberate failure to meet climate goals.’”

Corporate lobbyists are even pressing states to punish corporations (by withdrawing pension funds etc.) that dare even to provide information on environmental impacts of their policies. No stone is left unturned. Every opportunity to destroy must be exploited, no matter how slight, following Marx’s script of capitalism going berserk.

It is not really surprising that once Reagan and Thatcher launched the current era of savage class war, removing all constraints, the masters used the opportunity to pursue their “vile maxim, all for ourselves and nothing for anyone else,” as Smith advised us 250 years ago.

There is a certain logic behind it. The rules of the game are that you expand profit and market share, or you lose out. For self-delusion, it suffices to hold out the thin hope that maybe our technical culture will find some answers.

There is an alternative to the resolute march toward suicide. The distribution of power can be changed by an aroused public with its own very different priorities, such as surviving in a livable world. The current masters can be controlled on a path toward elimination of their illegitimate authority. The rules of the game can be changed, in the short term modified sufficiently to enable humankind to adopt the means that have been spelled out in detail to “step back from the abyss.” Read more

What The Failure Of Liz Truss’s Economic Agenda In The UK Can Teach The U.S.

Americans, relieved that they were rid of Donald Trump and his incessant scandals, looked gleefully to their neighbors across the Atlantic as British Prime Minister Liz Truss resigned after a mere 45 days in office. Truss had the shortest term of any British prime minister in history, disgraced by the consequences of her own economic prescriptions. There is a lesson to be learned from Truss’s rise and rapid downfall that applies to the United States, a nation beset by similar economic troubles but with a very different governmental structure.

The main takeaway from Truss’s downfall is that tackling inflation by rewarding the rich is a fool’s errand. Fashioning herself after Margaret Thatcher, the godmother of conservative capitalism, Truss had hoped to join the ranks of former prime ministers Tony Blair and David Cameron as a champion of “trickle-down” policies.

A central idea favored by Thatcherites—one that may sound familiar to Americans—is that when ordinary people are struggling, leaders must ensure the rich get richer so that the crumbs of their excesses will trickle down to the poor. Going hand in hand with this is the aggressive deregulation of industries to free them from the fetters of any protective measures that could impact profit margins.

Here in the U.S., President Ronald Reagan promoted this ludicrous concept in the 1980s as perhaps the grandest grift of all time, overseeing massive tax cuts for the wealthiest Americans and an aggressive deregulatory agenda. According to the Center for American Progress, when “Reagan took office in 1981, the marginal tax rate for the highest income bracket was 70 percent, but that fell to just 28 percent by the time he left office.”

In spite of decades of evidence that trickle-down economics doesn’t work, Republicans, when in control of the U.S. Congress and the presidency, have aggressively pushed through the same policies. Recall the 2017 tax reform bill forced through the legislative process by then-Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and signed into law by Trump. That bill continued what Reagan started by infusing cash at the very top in the form of tax cuts. It too, like its predecessors, failed.

Truss repackaged this same grift in the UK, with critics coining a new moniker for it: Trussonomics. Influenced by right-wing think tanks such as the Adam Smith Institute and the Institute of Economic Affairs, she pushed a “mini-budget” centered on major tax cuts for the wealthiest in Britain with no plan on how to compensate for the loss in revenues.

The Guardian’s economics correspondent Richard Partington explained that this triggered “a run on sterling, gilt market freefall and spooked global investors. Even the International Monetary Fund (IMF) intervened with a stunning public rebuke.” The British pound plummeted in value, and the Bank of England was forced to intervene by buying up bonds and raising interest rates. Eventually, members of Parliament began expressing enough loss of confidence in the new prime minister that Truss was forced to resign just over six weeks into her tenure.

Since the 1980s, both Republican and Democratic presidents in the U.S. embraced “Reaganomics,” in spite of critics repeatedly calling out the lunacy of enriching the wealthy to address poverty. By the time Joe Biden took office in January 2021, there was so much damage done that the new president felt moved to articulate that trickle-down economics doesn’t work. Biden repeated his criticisms as Truss took office, saying on Twitter in September 2022, “I am sick and tired of trickle-down economics. It has never worked.”

But talk is cheap, and another major lesson for Americans is that while it’s easy to find relief in our more stable system of government in which presidential elections are prescribed every four years, Britain’s less stable parliamentary system is far more responsive to popular will.

The best example of this—one that stands in stark contrast to the U.S.—is Britain’s National Health Service (NHS), a free, government-funded universal health care system that is the envy of Americans. In 1948, Aneurin Bevan, Britain’s then-health secretary, promoted the idea of a health care system that would serve all people. According to historian Anthony Broxton, Bevan pushed a parliamentary vote on the bill that would create the NHS, asking, “Why should the people wait any longer?”

Americans have waited and waited for a similar health care system. We are still waiting. A New York Times analysis explained how health care spending in the U.S. began getting out of control at the precise time when Reagan-era deregulation began. Decades of attempts to install a universal, government-funded free health care system in the U.S. have failed.

In an MSNBC op-ed, Nayyera Haq wrote, “in the nearly 250 years since the founding of the United States, American government has not followed Britain’s path of providing a universal health care system or welfare programs for the majority of the population.” Haq concluded, “The elevation of status quo over popular will has all but frozen the ability to respond to that will, weakening the American system far more than Truss’ tenure will destabilize Britain.”

While Americans can’t very well switch our government system into a parliamentary one, we do have midterm elections in just a few weeks. It turns out trickle-down economics is indeed on the ballot, and Republicans are using every means at their disposal to ensure its win.

The GOP has rigged elections in its favor via a cunning combination of gerrymandered districts, voting laws that thwart likely Democratic voters, and legislative control at the state level where electoral rules are decided. In Florida, Republican governor Ron DeSantis has embraced antidemocratic tactics to such an extent that he created a police force to arrest largely Black (and therefore likely-to-be-Democratic) voters who he claims are casting ballots illegally. In other words, Republicans have engineered a system of minority rule bordering on fascism.

Blowing wind into their sails is the corporate media, insisting that worries over inflation could help Republicans win majorities in both houses of Congress—in spite of decades of evidence that the GOP has a record of economic failures. It has become a central Republican talking point to inflate—pun intended—worries about rising prices, blame Democrats for inflation, and make the case for their own electoral victories. Economist Dean Baker criticized the media for “hyping inflation pretty much non-stop for the last year and a half.”

While polls show that relentless coverage of inflation has moved voters toward Republican candidates, few outlets are asking questions about the GOP’s plan to tackle inflation. House Republican leader Kevin McCarthy has published a rosy plan, very thin on specifics, to fix the nation’s economic woes if his party wins majorities. A one-page description of his plan includes a vague prescription to “bring stability to the economy through pro-growth tax and deregulatory policies.”

In other words, Republicans are yet again promising to deliver a wolf in sheep’s clothing. Call it Reaganomics, Thatcherism, or Trussonomics, trickle-down economics is the great lie that has failed time and again. If Truss’s spectacular fall should teach Americans anything, it is that it will fail again. Unlike the Brits, we’re likely to be stuck with the ill effects of such failure for a lot longer.

Source: Independent Media Institute

This article was produced by Economy for All, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

Sonali Kolhatkar is an award-winning multimedia journalist. She is the founder, host, and executive producer of “Rising Up With Sonali,” a weekly television and radio show that airs on Free Speech TV and Pacifica stations. Her forthcoming book is Rising Up: The Power of Narrative in Pursuing Racial Justice (City Lights Books, 2023). She is a writing fellow for the Economy for All project at the Independent Media Institute and the racial justice and civil liberties editor at Yes! Magazine. She serves as the co-director of the nonprofit solidarity organization the Afghan Women’s Mission and is a co-author of Bleeding Afghanistan. She also sits on the board of directors of Justice Action Center, an immigrant rights organization.