The Colonizer’s Mask Has Slipped To The Floor

No Comments yet 01-15-2025 ~ A decade ago, on a road north of Bamako, Mali, the jeep I was driving in had to pull off the road to permit a French military convoy to pass. The convoy was on its way to the main airfield used by the French air force as a part of Operation Serval (2013–2014). It was a long, dusty wait as the trucks went along the road, struggling a little in the mud that had begun to claim the roadway. I waved to some soldiers, just to be polite, but got a firm look from them. I could only imagine what they were thinking, so far from home, so confused about their mandate.

01-15-2025 ~ A decade ago, on a road north of Bamako, Mali, the jeep I was driving in had to pull off the road to permit a French military convoy to pass. The convoy was on its way to the main airfield used by the French air force as a part of Operation Serval (2013–2014). It was a long, dusty wait as the trucks went along the road, struggling a little in the mud that had begun to claim the roadway. I waved to some soldiers, just to be polite, but got a firm look from them. I could only imagine what they were thinking, so far from home, so confused about their mandate.

Something about the situation made me think of the cartoon Beau Peep, about a British man who joined the French Foreign Legion that was deployed in northern Africa so that he could escape from his wife Doris. In fact, the character that I remembered was Beau Peep’s commanding officer, Colonel Escargot, who believed that while stuck in the Sahara Desert he was in a conflict with “those warmongers of Switzerland” (January 1986). There was something about Brigadier General Bernard Barrera, who commanded Operation Serval, that reminded me of Colonel Escargot: “What are we doing here,” he seemed to say when he came out in public.

When the convoy had gone by, my friends in the jeep said, “Let’s see how long they last.” It was a worthwhile comment. When there is no good reason for an occupying force to be in a foreign environment, they often depart more silently than they arrive. Besides, troops from the Global North no longer wanted to operate in African and Asian countries when they were not protected by immunity agreements. For instance, the United States military had insisted on a Status-of-Forces agreement with the Iraqi parliament, and when the Iraqis decided not to renew that in 2011, U.S. forces began to leave the country (many remain in a backroom deal). Already, rumors had begun to slip in from northern Mali that French aircraft had struck and killed civilians. When will Les Toubab (the Europeans) leave?

It was in Bamako a decade ago that I first heard the phrase—“France dégage” or “France, Get Out”—in reference to the intervention of French troops. Anyone who was following the situation of the French intervention knew that France had caused the very problem that it had now come to solve: the French-engineered attack by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) on Libya in 2011 had provided air cover for jihadi groups, who then made a dash for Algeria and northern Mali. The problem had been caused by La mêre patrie, as France is often ironically called, the motherland. Even if this claim that France is to blame is often inflated, in this case, it was accurate.

One of my friends in Mali, who always used the phrase “French-backed al-Qaeda,” told me that “French-backed al-Qaeda had captured land that is about the size of France.” This includes the three major Malian cities of Gao, Kidal, and Timbuktu. I had been fascinated by Gao, which had become the cocaine capital of Mali; cocaine from Latin America was being flown there, to be driven across the Sahara, and then taken to Marseille to enter the European market. Under al-Qaeda, the coke stopped moving for a little while, but it appeared that the smugglers quickly made a deal with al-Qaeda’s branch of cigarette smugglers to keep the product on the road. The rhetoric of La mêre patrie was a cruel joke.

None of the explanations by François Hollande, then the president of France, for the continued intervention (la lutte contre le terrorisme, le jihadisme, etc.) made sense. It was even more peculiar to be sitting in the Sahel and reading a story about the release of two French pilots—Bruno Odos and Pascal Fauret—who had flown for NATO in the 1999 destruction of Yugoslavia, had been arrested in the Dominican Republic as part of the Air Cocaine affair, and had then been released through pressure from the French government. There was no higher ground here. Between the French government, the cocaine, cigarette, and human smugglers, and al-Qaeda, they were all slipping for the lowest surface possible.

It was not hard to anticipate the cycles of popular protest that started in Mali, in fact only a few days after the French troops entered the country and then developed across the Sahel from Senegal to Niger. The phrase “France degage” was infectious, but there were other phrases. In Senegal, the movement just said, “Y’en a Marre,” (We are Fed Up). It was out of that wave of protest that the vehicle for popular distress became the military coup led by patriotic officers. There was no other alternative that presented itself. Very quickly, these patriotic coups made decisions that have now become general across the region. The most important framework was to demand that their governments exercise sovereignty not only in terms of forces (get the French military out) but also in terms of economic policy. But first, the French, told to get out in waves:

Mali, February 2022

Burkina Faso, February 2023

Niger, December 2023

Chad, December 2024

Senegal, December 2024

Ivory Coast, December 2024

Add to this the ferociousness of the anti-French attitude now growing in its far-flung Overseas Territories, from New Caledonia’s Front de Libération Nationale Kanake et Socialiste to the angry citizens of Mayotte.

No wonder France’s President Emmanuel Macron behaved like an old colonial officer when he spoke in Paris on January 6, 2025. France, Macron said, had not been forced out of the Sahel but had decided to “reorganize itself.” “France is not in decline in Africa,” he insisted with a churlish hollowness. It is not the French colonial attitude and practice that is to blame, he said, but “a contemporary Pan-Africanism of good quality that uses a sort of postcolonial discourse, while having back-channel support from today’s imperialists.” The rambling from Macron was familiar. This is the imperial master at the podium, saying whatever he wants, claiming Reason as his own and manipulation as his enemy. By “today’s imperialists,” Macron referred to “the interests of Russia or others in Africa,” not even having the guts to name China (for who else would be the “others” that detained Macron?). The keywords were all there: terrorism, disinformation, the West.

Then, Macron said what he had come to say. “Ingratitude is a disease that cannot be transmitted to humans. I say this for all the African rulers who haven’t the courage to wear it in the face of public opinion. None of them would be in a sovereign country today if the French army hadn’t been deployed in this region.” Be grateful. We made you. This is the old colonial attitude that would be familiar to the old French colonial heads Louis Faidherbe (Senegal), Henri Gouraud (Syria), Paul Doumer (Indochina), and Joseph Gallieni (Madagascar), nasty men, all of them.

Ibrahim Traoré of Burkina Faso and Assimi Goïta of Mali were at the inauguration of Ghana’s new president John Mahama. Macron was not there. When Traoré went to the stage to greet Mahama, he was the only one to get a loud applause.

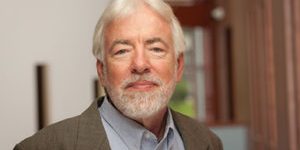

By Vijay Prashad

Author Bio: This article was produced by Globetrotter. Vijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor, and journalist. He is a writing fellow and chief correspondent at Globetrotter. He is an editor of LeftWord Books and the director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. He has written more than 20 books, including The Darker Nations and The Poorer Nations. His latest books are On Cuba: Reflections on 70 Years of Revolution and Struggle (with Noam Chomsky), Struggle Makes Us Human: Learning from Movements for Socialism, and (also with Noam Chomsky) The Withdrawal: Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan, and the Fragility of U.S. Power.

Source: Globetrotter

You May Also Like

Comments

Leave a Reply