Levende-Doden ~ Summary

‘Living-Dead: African-Surinamese perceptions, practices and rituals surrounding death and mourning’ describes and interprets the death culture of the descendants of African slaves, Creoles and Maroons, in Suriname. The book offers an integrated approach in which a wide range of attitudes comes to the fore, and uncommon (supernatural, bad or tragic) and common (natural, good) death are studied together. In this way, the study presents a comparative and reflexive perspective that reconciles ethnographic detail with middle range theories.

‘Living-Dead: African-Surinamese perceptions, practices and rituals surrounding death and mourning’ describes and interprets the death culture of the descendants of African slaves, Creoles and Maroons, in Suriname. The book offers an integrated approach in which a wide range of attitudes comes to the fore, and uncommon (supernatural, bad or tragic) and common (natural, good) death are studied together. In this way, the study presents a comparative and reflexive perspective that reconciles ethnographic detail with middle range theories.

The book is guided by two leitmotifs. The first concerning the coexistence of tradition and modernity or the phenomenon of multitemporal heterogeneity, arguing that African-Surinamese actors always live, on the one hand, in terms of conflicting demands, desires and expectations associated with voices of authority and, on the other, with the idiosyncratic aspirations of the individual. Processes like creolization, syncretization/anti-syncretization and de-/retraditionalization play a prominent role in this dialectic and, consequently, in the construction of African-Surinamese death culture as well as people’s changing attitudes towards dying, death and mourning.

Despite this dynamic nature, African-Surinamese culture is characterized by an inevitable constant that forms the second leitmotif of this study: the living-dead. Throughout this study it appears that within the African-Surinamese worldview and spiritual-religious orientation, (biological) death does not necessarily mean the end of life. Death rather implies a continuation of life in another form, in which contacts between the living and the deceased (or their spirits) are still possible. The dead are not dead: they are the living-dead who might interfere in people’s lives – as spiritual entities or simply as a lasting remembrance. Living-dead have therefore to be handled with utmost care and respect, while the rituals regarding death, burial and mourning are considered as the most important rites de passage of African-Surinamese culture.

Because of the enormous significance of the living-dead and the subsequent transitional rituals, an important part of this book consists of the description, analysis and interpretation of the ritual process that starts at the deathbed or even before the dying hour. In the conceptualization of death as a process and transition, I draw heavily on Van Gennep’s model of rites of passage, Hertz’s study of liminal rituals as well as his insights into the relationship between corpse, soul and mourners, and several contemporary followers of these founding fathers. In order to grasp all the different ritual stages that surround the process of dying, death and mourning, one first needs an understanding of the sociocultural and religiousspiritual perceptions behind the ritual practices as well as an outline of the social-economic and political context in which people live, die, bury, grief and mourn.

The introductory chapter of this book discusses therefore not only some key concepts and approaches that molded my notion of conducting ethnographic fieldwork on African-Surinamese death culture, but portrays also the precarious situation in which the Surinamese society found itself during my research (1999, 2000). In brief, the country and a large part of its population suffered enormously by a severe economic crisis and a grinding poverty that, because of political and financial-monetary misgovernment, was becoming structural and most in line with Latin-America. At the edge of a new millennium Suriname had deteriorated into one of the worst functioning economies of the region. The process of marginalization hit many if not all my informants in the field, and caused a chasm between a small and privileged group of rich haves (gudusma, elite) and a growing mass of poor have-nots (tye poti). The latter increasingly lacked access to health care, suffered various sanitary inconveniences and subsequent diseases, and saw itself exposed to all kinds of life-threatening conditions, ‘new’ diseases and causes of death. Read more

Levende-Doden ~ Glossarium, Bijlagen I, II & Literatuurlijst

Glossarium – PDF

Bijlage I – Interviews – PDF

Bijlage II – Casussen, situatie-analyses & observaties[i] – PDF

i. Nota bene: het betreft hier volledig uitgewerkte casussen. Veldaantekeningen betreffende allerhande dagelijkse of frequente activiteiten, zoals begraafplaatsbezoek, ‘routinematig’ bijwonen van begrafenissen, mortuariumbezoek, rouwvisite en veel hanging around, zijn niet opgenomen in deze lijst.

Literatuur

Abbenhuis, M.F., 1966 Honderd jaar missiewerk in Suriname door de Redemptoristen, 1866-1966. Paramaribo: [s.n.].

Agerkop, T., 1982 Saramaka Music and Motion. Anales Del Caribe 2: 231-245. Read more

Carole McGranahan & Uzma Z. Rizvi (Eds,) ~ Decolonizing Anthropology

Just about 25 years ago Faye Harrison poignantly asked if “an authentic anthropology can emerge from the critical intellectual traditions and counter-hegemonic struggles of Third World peoples? Can a genuine study of humankind arise from dialogues, debates, and reconciliation amongst various non-Western and Western intellectuals — both those with formal credentials and those with other socially meaningful and appreciated qualifications?” (1991:1). In launching this series, we acknowledge the key role that Black anthropologists have played in thinking through how and why to decolonize anthropology, from the 1987 Association of Black Anthropologists’ roundtable at the AAAs that preceded the 1991 volume on Decolonizing Anthropology edited by Faye Harrison, to the World Anthropologies Network, to Jafari Sinclaire Allen and Ryan Cecil Jobson’s essay out this very month in Current Anthropology on“The Decolonizing Generation: (Race and) Theory in Anthropology since the Eighties.”

Just about 25 years ago Faye Harrison poignantly asked if “an authentic anthropology can emerge from the critical intellectual traditions and counter-hegemonic struggles of Third World peoples? Can a genuine study of humankind arise from dialogues, debates, and reconciliation amongst various non-Western and Western intellectuals — both those with formal credentials and those with other socially meaningful and appreciated qualifications?” (1991:1). In launching this series, we acknowledge the key role that Black anthropologists have played in thinking through how and why to decolonize anthropology, from the 1987 Association of Black Anthropologists’ roundtable at the AAAs that preceded the 1991 volume on Decolonizing Anthropology edited by Faye Harrison, to the World Anthropologies Network, to Jafari Sinclaire Allen and Ryan Cecil Jobson’s essay out this very month in Current Anthropology on“The Decolonizing Generation: (Race and) Theory in Anthropology since the Eighties.”

Read more: http://savageminds.org/series/decolonizing-anthropology/

Fountain Hughes ~ Voices From The Days Of Slavery

Fountain Hughes (age 101 at the time of this interview) recalls his younger years when he and his family lived as slaves as well as some good advice on how to spend money.

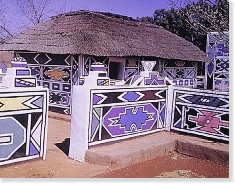

The Ndebele Nation

12-05-2015 ~ With an Introduction by Milton Keynes

The Ndebele of Zimbabwe, who today constitute about twenty percent of the population of the country, have a very rich and heroic history. It is partly this rich history that constitutes a resource that reinforces their memories and sense of a particularistic identity and distinctive nation within a predominantly Shona speaking country. It is also partly later developments ranging from the colonial violence of 1893-4 and 1896-7 (Imfazo 1 and Imfazo 2); Ndebele evictions from their land under the direction of the Rhodesian colonial settler state; recurring droughts in Matabeleland; ethnic forms taken by Zimbabwean nationalism; urban events happening around the city of Bulawayo; the state-orchestrated and ethnicised violence of the 1980s targeting the Ndebele community, which became known as Gukurahundi; and other factors like perceptions and realities of frustrated economic development in Matabeleland together with ever-present threats of repetition of Gukurahundi-style violence—that have contributed to the shaping and re-shaping of Ndebele identity within Zimbabwe.

The Ndebele history is traced from the Ndwandwe of Zwide and the Zulu of Shaka. The story of how the Ndebele ended up in Zimbabwe is explained in terms of the impact of the Mfecane—a nineteenth century revolution marked by the collapse of the earlier political formations of Mthethwa, Ndwandwe, and Ngwane kingdoms replaced by new ones of the Zulu under Shaka, the Sotho under Moshweshwe, and others built out of Mfecane refugees and asylum seekers. The revolution was also characterized by violence and migration that saw some Nguni and Sotho communities burst asunder and fragmenting into fleeing groups such as the Ndebele under Mzilikazi Khumalo, the Kololo under Sebetwane, the Shangaans under Soshangane, the Ngoni under Zwangendaba, and the Swazi under Queen Nyamazana. Out of these migrations emerged new political formations like the Ndebele state, that eventually inscribed itself by a combination of coercion and persuasion in the southwestern part of the Zimbabwean plateau in 1839-1840. The migration and eventual settlement of the Ndebele in Zimbabwe is also part of the historical drama that became intertwined with another dramatic event of the migration of the Boers from Cape Colony into the interior in what is generally referred to as the Great Trek, that began in 1835. It was military clashes with the Boers that forced Mzilikazi and his followers to migrate across the Limpopo River into Zimbabwe.

As a result of the Ndebele community’s dramatic history of nation construction, their association with such groups as the Zulu of South Africa renowned for their military prowess, their heroic migration across the Limpopo, their foundation of a nation out of Nguni, Sotho, Tswana, Kalanga, Rozvi and ‘Shona’ groups, and their practice of raiding that they attracted enormous interest from early white travellers, missionaries and early anthropologists. This interest in the life and history of the Ndebele produced different representations, ranging from the Ndebele as an indomitable ‘martial tribe’ ranking alongside the Zulu, Maasai and Kikuyu, who also attracted the attention of early white literary observers, as ‘warriors’ and militaristic groups. This resulted in a combination of exoticisation and demonization that culminated in the Ndebele earning many labels such as ‘bloodthirsty destroyers’ and ‘noble savages’ within Western colonial images of Africa.

Ndebele History

Ndebele History

With the passage of time, the Ndebele themselves played up to some of the earlier characterizations as they sought to build a particular identity within an environment in which they were surrounded by numerically superior ‘Shona’ communities. The warrior identity suited Ndebele hegemonic ideologies. Their Shona neighbours also contributed to the image of the Ndebele as the militaristic and aggressive ‘other’. Within this discourse, the Shona portrayed themselves as victims of Ndebele raiders who constantly went away with their livestock and women—disrupting their otherwise orderly and peaceful lives. A mythology thus permeates the whole spectrum of Ndebele history, fed by distortions and exaggerations of Ndebele military prowess, the nature of Ndebele governance institutions, and the general way of life.

My interest is primarily in unpacking and exploding the mythology within Ndebele historiography while at the same time making new sense of Ndebele hegemonic ideologies. My intention is to inform the broader debate on pre-colonial African systems of governance, the conduct of politics, social control, and conceptions of human security. Therefore, the book The Ndebele Nation (see: below) delves deeper into questions of how Ndebele power was constructed, how it was institutionalized and broadcast across people of different ethnic and linguistic backgrounds. These issues are examined across the pre-colonial times up to the mid-twentieth century, a time when power resided with the early Rhodesian colonial state. I touch lightly on the question of whether the violent transition from an Ndebele hegemony to a Rhodesia settler colonial hegemony was in reality a transition from one flawed and coercive regime to another. Broadly speaking this book is an intellectual enterprise in understanding political and social dynamics that made pre-colonial Ndebele states tick; in particular, how power and authority were broadcast and exercised, including the nature of state-society relations.

What emerges from the book is that while the pre-colonial Ndebele state began as an imposition on society of Khumalo and Zansi hegemony, the state simultaneously pursued peaceful and ideological ways of winning the consent of the governed. This became the impetus for the constant and ongoing drive for ‘democratization,’ so as contain and displace the destructive centripetal forces of rebellion and subversion. Within the Ndebele state, power was constructed around a small Khumalo clan ruling in alliance with some dominant Nguni (Zansi) houses over a heterogeneous nation on the Zimbabwean plateau. The key question is how this small Khumalo group in alliance with the Zansi managed to extend their power across a majority of people of non-Nguni stock. Earlier historians over-emphasized military coercion as though violence was ever enough as a pillar of nation-building. In this book I delve deeper into a historical interrogation of key dynamics of state formation and nation-building, hegemony construction and inscription, the style of governance, the creation of human rights spaces and openings, and human security provision, in search of those attributes that made the Ndebele state tick and made it survive until it was destroyed by the violent forces of Rhodesian settler colonialism.

The book takes a broad revisionist approach involving systematic revisiting of earlier scholarly works on the Ndebele experiences in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and critiquing them. A critical eye is cast on interpretation and making sense of key Ndebele political and social concepts and ideas that do not clearly emerge in existing literature. Throughout the book, the Ndebele historical experiences are consistently discussed in relation to a broad range of historiography and critical social theories of hegemony and human rights, and post-colonial discourses are used as tools of analysis.

Empirically and thematically, the book focuses on the complex historical processes involving the destruction of the autonomy of the decentralized Khumalo clans, their dispersal from their coastal homes in Nguniland, and the construction of Khumalo hegemony that happened in tandem with the formation of the Ndebele state in the midst of the Mfecane revolution. It further delves deeper into the examination of the expansion and maturing of the Ndebele State into a heterogeneous settled nation north of the Limpopo River. The colonial encounter with the Ndebele state dating back to the 1860s culminating in the imperialist violence of the 1890s and the subsequent colonization of the Ndebele in 1897 is also subjected to consistent analysis in this book.

What is evident is that the broad spectrum of Ndebele history was shot through with complex ambiguities and contradictions that have so far not been subjected to serious scholarly analysis. These ambiguities include tendencies and practices of domination versus resistance as the Ndebele rebelled against both pre-colonial African despots like Zwide and Shaka as well as against Rhodesian settler colonial conquest. The Ndebele fought to achieve domination, material security, political autonomy, cultural and political independence, social justice, human dignity, and tolerant governance even within their state in the face of a hegemonic Ndebele ruling elite that sought to maintain its political dominance and material privileges through a delicate combination of patronage, accountability, exploitation, and limited coercion.

The overarching analytical perspective is centred on the problem of the relation between coercion and consent during different phases of Ndebele history up to their encounter with colonialism. Major shifts from clan to state, migration to settlement, and single ethnic group to multi-ethnic society are systematically analyzed with the intention of revealing the concealed contradictions, conflict, tension, and social cleavages that permitted conquest, desertions, raiding, assimilation, domination, and exploitation, as well as social security, communalism, and tolerance. These ideologies, practices and values combined and co-existed uneasily, periodically and tendentiously within the Ndebele society. They were articulated in varied and changing idioms, languages and cultural traditions, and underpinned by complex institutions. Read more

Margot Leegwater ~ Sharing Scarcity: Land Access And Social Relations In Southeast Rwanda

Land is a crucial yet scarce resource in Rwanda, where about 90% of the population is engaged in subsistence farming, and access to land is increasingly becoming a source of conflict. This study examines the effects of land-access and land-tenure policies on local community relations, including ethnicity, and land conflicts in post-conflict rural Rwanda. Social relations have been characterized by (ethnic) tensions, mistrust, grief and frustration since the end of the 1990-1994 civil war and the 1994 genocide. Focusing on southeastern Rwanda, the study describes the negative consequences on social and inter-ethnic relations of a land-sharing agreement that was imposed on Tutsi returnees and the Hutu population in 1996-1997 and the villagization policy that was introduced at the same time. More recent land reforms, such as land registration and crop specialization, appear to have negatively affected land tenure and food security and have aggravated land conflicts. In addition, programmes and policies that the population have to comply with are leading to widespread poverty among peasants and aggravating communal tensions. Violence has historically often been linked to land, and the current growing resentment and fear surrounding these land-related policies and the ever-increasing land conflicts could jeopardize Rwanda’s recovery and stability.

Land is a crucial yet scarce resource in Rwanda, where about 90% of the population is engaged in subsistence farming, and access to land is increasingly becoming a source of conflict. This study examines the effects of land-access and land-tenure policies on local community relations, including ethnicity, and land conflicts in post-conflict rural Rwanda. Social relations have been characterized by (ethnic) tensions, mistrust, grief and frustration since the end of the 1990-1994 civil war and the 1994 genocide. Focusing on southeastern Rwanda, the study describes the negative consequences on social and inter-ethnic relations of a land-sharing agreement that was imposed on Tutsi returnees and the Hutu population in 1996-1997 and the villagization policy that was introduced at the same time. More recent land reforms, such as land registration and crop specialization, appear to have negatively affected land tenure and food security and have aggravated land conflicts. In addition, programmes and policies that the population have to comply with are leading to widespread poverty among peasants and aggravating communal tensions. Violence has historically often been linked to land, and the current growing resentment and fear surrounding these land-related policies and the ever-increasing land conflicts could jeopardize Rwanda’s recovery and stability.

Full text book: http://www.ascleiden.nl/news/sharing-scarcity