Isabella Marie Weber – The Peculiarities Of China’s Economic Model

Isabella Weber – PERI Research Associate and Research Leader in China Studies; Assistant Professor of Economics

This is part of PERI’s economist interview series, hosted by C.J. Polychroniou. The Series: https://www.peri.umass.edu/peri-economist-interview-series

Read Isabella Weber’s bio here.

C.J. Polychroniou: How did you get into economics?

Isabella Maria Weber: I got into economics through my interest in politics, in particular global questions. I realized that the political is inherently economic and the economic inherently political. If we want to understand how we can work towards positive change politically, we have to understand the material foundations of our society. If we want to make sense of the major shifts in our global political system, we have to understand the long-term economic dynamics. Coming from this angle, economics for me must take the form of political economy.

CJP: What do you consider to be the main issue in your research?

IMW: The broad question that motivates my research is how we can make sense of the major changes in the global economy that are unfolding in front of our eyes – at a dramatically accelerated pace since the COVID-19 pandemic. Since the Industrial Revolution in the late 18thcentury, we have lived in a world of a globalizing capitalist economic system, first under British than under U.S. hegemony. This phase is coming to a close with the gradual rise of China – not necessarily to one of dominance but to a more eye-level position. In my research, I pursue two related questions that aim to make a small contribution to this broad challenge: First, I have studied the intellectual foundations behind China’s economic reforms that set the country on the path of its current ascent. Second, I am leading a research project in which we examine the long-term evolution of global export patterns across the last and present era of globalization. The aim here is to understand path dependency and path defiance in the global division of labor. This theme grew out of earlier work on the US-China trade imbalance. In a third strand of my research, I have been investigating foundational questions of the nature of money and the driving forces of international trade for the purpose of placing my work on firmer theoretical grounds.

CJP: Why did you choose to specialize on the Chinese economy?

IMW: I am answering your questions as we watch the global economy collapse under the threat of COVID-19. There is no question that the political and economic power relations between the U.S. and China are changing. Many people in the U.S. and Europe alike are reacting to this uncertain dynamic with fear and, unfortunately, with increasingly racist, anti-Chinese sentiments. In order to work toward a peaceful navigation of the deep structural changes in the world economy, I believe that there is an urgent need for a better understanding of the logic of China’s political economy. Instead of measuring China’s system against the European or American experiences or some standard economics model, we need to study China’s path on its own grounds, while taking into account at the same time its global connectedness. I have specialized in the Chinese economy for the very purpose of making some kind of a contribution to this project.

CJP: How real is the so-called Chinese economic miracle?

IMW: The Oxford English Dictionary defines a “miracle” as a “marvelous event not ascribable to human power.” China’s economic development of the last four decades is certainly astonishing and as such marvelous. But it is by no means the result of some overnight wonder created by supernatural agency or luck. According to Maddison estimates of 2001, China accounted for about one third of the world’s GDP in 1850. Its share had fallen to below 5 percent in 1950, when China was one of the poorest countries in the world. Today China is responsible for about a fifth of the world’s GDP. These are rough measures, but the trend is obvious. China’s Communist revolution was about much higher aspirations than economic development. But it was clear from the beginning that industrialization and higher living standards were core requirements. Of course, China gave up long ago on Mao’s vision of revolution. But the pursuit of economic progress has continued across dramatically different political phases since 1949. China’s gradual return to a more prominent position in the world economy is not the result of a miracle, but of decades of hard work and heterodox economic policymaking. In a forthcoming book of mine, I argue that China’s economic leaders learned key lessons from the history of economic warfare in the 1930s and 1940s. At the heart of this strategy is the articulation of clear broad goals which are being pursued by flexibly utilizing prevailing economic dynamics and structures.

CJP: How did China manage to liberalize its economy while avoiding shock therapy, which is pretty much what happened in virtually all transition economies in Eastern Europe, Russia, and Latin America?

IMW: We often imagine of China’s gradual economic reforms as having been without an alternative. In fact, the 1980s marked a crossroads in the recent history of China and of global capitalism, as I show in my forthcoming book “How China Escaped Shock Therapy.” China too had very concrete plans for far-ranging overnight liberalizations. Had China implemented the policy of “shock therapy,” it would most likely have generated the same devastating results that we have observed elsewhere, but on a much larger scale. China would have mirrored Russia’s fall, but starting from a much lower level.

The basic premise of shock therapy is that all institutions of direct state control over the economy must be destroyed to make space for the market. Instead, China pursued a strategy of market creation that utilized the institutions of the planned economy. It kept the core of the planned industrial economy working, while transforming the old institutions into market players by first allowing for market activities on the margins. This strategy is manifested in the dual-track price system. Under this system, state-owned enterprises and farmers had to deliver the state-set quotas at a state-set price, but if they managed to produce more, they could market their surplus at market prices. In this way, China’s economy was gradually marketized under active bureaucratic guidance by reorienting its core economic institutions from the plan to the market. Non-essentials were liberalized first. Surpluses as well as sectors producing non-basic goods were non-essentials. They could be completely marketized without immediately endangering the stability of the whole system. Yet, the marketization of these non-essential areas unleashed a dynamic that fundamentally transformed the whole political economy, including its core.[1] As a result of this strategy, China kept much closer control over core sectors of the economy, such as energy, steel, finance and infrastructure. This has allowed China to respond in a fine-grained and targeted way to the 2008 global financial crisis, and to the current economic collapse in light of COVID-19.

CJP: Could/should the Chinese model be emulated by other developing countries?

IMW: China had a very different starting point from most other developing countries today. From a longue durée perspective, China could build on a very long history of bureaucratic market creation and participation. Tools derived from the statecraft of playing the market were utilized during the revolutionary struggles and again in the reform era. Considering the more immediate context, the Mao era had laid strong foundations for China’s take off in terms of education, literacy, public health and basic industrialization. Most developing countries do not have those preconditions. It would therefore not make sense to simply copy China’s model. But there is a deeper reason for not copying China’s model that emerges from China’s own experience. It is extremely important to realize that China, too, did not simply copy foreign models. Chinese researchers and officials, in collaboration with international partners, studied carefully the experience of various other countries and drew lessons for the country’s own specific situation, adapting the insights to its concrete conditions, often with major problems in the process. This approach of careful study of the prevailing local condition and adaptation of foreign experiences is what other developing countries can learn from China. But there is no panacea that works for all. The Beijing Model should not replace the Washington Consensus. The lesson is that there is no easy universal solution, no policy package that can fix it all.

CJP: What’s your view on Trump’s trade war with China? More generally, do you think the Chinese economy poses threats to the U.S. economy and other countries’ economies? If so, should they do anything about it?

IMW: I think that the trade war is an extremely dangerous policy. If any further proof was needed – and I don’t think there is, COVID-19 is demonstrating in a morbid fashion just how closely integrated the world is with China, and vice versa. In the 1980s China retreated from its revolutionary ambitions and embarked on a path of reform using its state capacity to reintegrate into the global market. Since the 1990s, we have been living through a second peak of globalization in modern times. The last globalization ended with the First World War. The present one is collapsing as I am writing. In such a situation, we need international collaboration, not war of any kind. I don’t think the Chinese economy, taken by itself, poses a threat to the U.S. or to other countries. Crises of this historical moment don’t have a nationality; they lie in the nature of the global system. The real threat results from the exploitation of this crisis by nationalists and racists. To confront this threat, we have to improve our understanding of China, instead of feeding into scapegoat narratives.

Reference:

[1] I spell this out in greater detail in this interview: https://www.peri.umass.edu/economists/isabella/item/1206-the-making-of-china-s-economic-reforms

Utopia en omstreken: imaginaire gebieden

Behalve fictieve personen, zoals Anton Steenwijk en Josef K., David Copperfield en Nathan Sid, heeft de literatuur ook fictieve steden en landen opgeleverd. Lewis Carroll liet Alice haar avonturen beleven in Wonderland, Jonathan Swift stuurde Lemuel Gulliver in Gulliver’s Travels (1726) onder meer naar Lilliput, Brobdingnag, Lagado, Glubbdubrib en Houyhnhnmland.

Behalve fictieve personen, zoals Anton Steenwijk en Josef K., David Copperfield en Nathan Sid, heeft de literatuur ook fictieve steden en landen opgeleverd. Lewis Carroll liet Alice haar avonturen beleven in Wonderland, Jonathan Swift stuurde Lemuel Gulliver in Gulliver’s Travels (1726) onder meer naar Lilliput, Brobdingnag, Lagado, Glubbdubrib en Houyhnhnmland.

J.R.R. Tolkien creëerde voor de In de ban van de ring-cyclus (1954-1955) zelfs een hele mythologie, inclusief landkaarten en taal, rond Middle-earth. Dat leverde welluidende namen op als Esgalduin, Nanduhirion, Angrenost en Nimrodel.

En zoals sommige fictieve personages, zoals de Jan en Erik in het werk van Wolkers, de Gerard in dat van Reve en de Maarten in dat van ‘t Hart, dicht in de buurt van het levende voorbeeld blijven, zo is in sommige van die fictieve gebieden zonder veel moeite de woonomgeving van de auteur te herkennen.

De Amerikaanse schrijver William Faulkner, geboren in de zuidelijke staat Mississippi, situeert een deel van zijn romans in het niet-bestaande Yoknapatawpha County, een streek in het noorden van Mississippi. En het Lahringen uit Vestdijks Anton Wachter-romans ligt wel erg dicht bij het Harlingen waar de schrijver geboren werd.

Maar een groot deel van die steden, streken en landen zijn speciaal voor het literaire werk bedacht en in het register van niet één atlas terug te vinden. Nou, drie dan: in de Amerikaanse Dictionary of Imaginary Places (1980), in Umberto Eco’s De geschiedenis van imaginaire landen en plaatsen (2013) en in de Atlas van imaginaire landen (2016) van Dominique Lanni.

Het aardige is dat die bedachte plaatsen soms een eigen leven zijn gaan leiden. Een mooi voorbeeld daarvan is Shangri-La, de lusthof in de roman Lost horizon (1933) van de Engelse schrijver James Hilton. Shangri-La, dat vermoedelijk ergens in Tibet ligt, is synoniem geworden met ‘paradijselijk oord’ en liet in die betekenis veel sporen na in de popmuziek. In de jaren vijftig ontstond in Amerika de meisjesgroep The Shangri-Las, die, behalve om hun suikerspinkapsels en zuurstokkleurige strechtbroeken, bekend werden met o.a. Remember (walking in the sand) en I can never go home anymore. The Kinks hadden in 1969 een hit met Shangri-La, de Nederlandse Elvis Presley, Jack Jersey, zette het bijna onuitspreekbare Sri Lanka, My Shangri-La op de plaat en in 1988 vertegenwoordigde Gerard Joling ons land op het Eurovisie Songfestival met Ik wil terug naar Shangri-La.

En om in de popmuziek te blijven: Xanadu, dat in 1968 de kleurrijke Britse groep Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick & Titch inspireerde tot The legend of Xanadu en in 1980 een hit opleverde voor Olivia Newton-John, stamt uit het (onvoltooid gebleven) gedicht ‘Kubla Khan’ van de Engelse poëet Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834), waarvan de eerste regels luiden: In Xanadu did Kubla Khan a stately pleasure-dome decree. Het moet waarschijnlijk in China gezocht worden, niet ver van Shangri-La. En ook het enorme landhuis van Charles Foster Kane in de film Citizen Kane (1941) van Orson Welles heet Xanadu.

Een vervolg van geheel andere orde kreeg Thule. Dat is de naam die in de klassieke oudheid gegeven werd aan een eiland dat zes dagen zeilen ten noorden van Schotland heette te liggen en dat als het einde van de wereld beschouwd werd. Sommige schrijvers zagen IJsland er voor aan, andere Shetland of zelfs de kust van Noorwegen. Het werd vooral bekend in de uitdrukking Ultima Thule – ‘het einde van de wereld’ – en komt in die zin al voor bij de Romeinse schrijvers Virgilius en Seneca.

In navolging van chemische elementen als berkelium en ytterbium, die hun naam kregen van de plaats waar ze gevormd werden (respectievelijk Berkeley in Californië en Ytterby in Zweden), dankt thulium zijn naam aan Thule. Het moet het enige chemische element zijn dat naar een niet-bestaande plaats vernoemd is, al gebiedt de volledigheid te wijzen op het element thorium, genoemd naar een fictieve figuur, de Germaanse dondergod Thor.

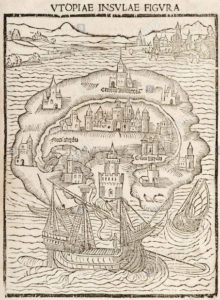

Het bekendste literaire land is waarschijnlijk Utopia (1516), het droomeiland uit het gelijknamige werk van Thomas More waar de ideale maatschappij zetelt. De naam is opgebouwd uit twee Griekse woorden, ou (niet) en topos (plaats), en kan dus vertaald worden met ‘Nergensland’. Het is niet alleen het bekendste, ook het invloedrijkste. Utopia komt ook voor in andere literaire werken – in Rabelais’ Gargantua en Pantagruel (1532-1564), bijvoorbeeld, waarin de laatste van deze twee reuzen het eiland bezoekt – en heeft een heuse utopische stroming in de literatuur op gang gebracht, met alle namen van dien. Daaronder valt Shangri-La, alsook het Oceana uit James Harringtons The Commonwealth of Oceana (1656) en het Macaria (letterlijk: Zaligland) van de Duitser Caspar Stiblinus.

Het bekendste literaire land is waarschijnlijk Utopia (1516), het droomeiland uit het gelijknamige werk van Thomas More waar de ideale maatschappij zetelt. De naam is opgebouwd uit twee Griekse woorden, ou (niet) en topos (plaats), en kan dus vertaald worden met ‘Nergensland’. Het is niet alleen het bekendste, ook het invloedrijkste. Utopia komt ook voor in andere literaire werken – in Rabelais’ Gargantua en Pantagruel (1532-1564), bijvoorbeeld, waarin de laatste van deze twee reuzen het eiland bezoekt – en heeft een heuse utopische stroming in de literatuur op gang gebracht, met alle namen van dien. Daaronder valt Shangri-La, alsook het Oceana uit James Harringtons The Commonwealth of Oceana (1656) en het Macaria (letterlijk: Zaligland) van de Duitser Caspar Stiblinus.

Maar er ontstond ook een stroming tegen al dat idealisme, en zo ontstond het begrip ‘distopia’.

Zo’n anti-utopia werd onder meer uitgewerkt door Samuel Butler, die zijn visie op de zorgenvrije gemeenschap geeft in Erewhon (1872), een anagram van nowhere. En ene E. Callenbach publiceerde in 1975 Ecotopia, waarin de overindustrialisatie van onze maatschappij wordt bekritiseerd (eco stamt van het Griekse oikos – ‘huis(gezin), familie’ – en komt tegenwoordig veel voor in samenstellingen die op het milieu betrekking hebben, zoals ecosysteem en ecotax).

Ook in de Nederlandse letteren zijn fictieve plaatsen geschapen. De Zwolse chirurgijn Hendrik Smeeks beschreef een imaginaire reis in Beschryvinge van het Magtig Koninkryk Krinke Kesmes (1708). Mooi zijn ook de twee namen in Simon Stijls toneelstuk De Torenbouw van het Vlek Brikkekiks in het landschap Batrachia (1787), een satire op de aanhouding van prinses Wilhelmina bij Goejanverwellesluis in dat jaar. Batrachia betekent ‘Kikkerland’ en in die context is Brikkekiks te interpreteren als kikkergekwaak.

De strijd tussen patriotten en orangisten speelde een rol in Reize door het Aapenland (1788), dat op naam staat van J.A. Schasz, M.D. Het is, net als bijvoorbeeld Gulliver’s Travels, een satirisch imaginair reisverhaal, een genre dat hem blijkbaar goed beviel, want hij schreef ook Reize door het Wonderland (1780) en Reize door het Land der Vrijwillige Slaaven (1790).

De strijd tussen patriotten en orangisten speelde een rol in Reize door het Aapenland (1788), dat op naam staat van J.A. Schasz, M.D. Het is, net als bijvoorbeeld Gulliver’s Travels, een satirisch imaginair reisverhaal, een genre dat hem blijkbaar goed beviel, want hij schreef ook Reize door het Wonderland (1780) en Reize door het Land der Vrijwillige Slaaven (1790).

Belcampo geeft een beeld van de wereld in het jaar 12.000 in zijn verhaal Voorland (1935), maar de aardigste in het Nederlands komen van de dichter Jean Pierre Rawie. Die woont in Groningen, maar hij wil daar in de datering van zijn brieven nog wel eens op variëren. In het door Boudewijn Buch samengestelde promotieboekje Buch Boeket 1 begint een brief van Rawie aan zijn uitgever met ‘Gromsk II IX MCMLXXXV’. Later verstuurde hij ook wel brieven vanuit Groomsbury, waarin behalve Groningen ook Bloomsbury doorklinkt, de kunstenaarswijk in Londen waaraan de Bloomsbury-groep rond Virginia en Leonard Woolf en Lytton Strachey haar naam ontleent.

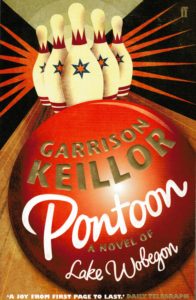

Mijn persoonlijke voorkeur gaat uit naar Lake Wobegon, het bescheiden plaatsje – smalltown in het Amerikaans – in de Amerikaanse staat Minnesota waar Garrison Keillor zijn Lake Wobegon Days (1985) gesitueerd heeft. Niet alleen omdat ik het persoonlijk bezocht heb (wat bij mijn weten de enige keer geweest is, dat ik in een fictief gebied liep), maar ook omdat er zo’n mooie vertaling van bestaat. In het Wobegon-meer waarnaar het dorp is genoemd, is zonder veel moeite de uitdrukking wo(e)begone te herkennen: treurig, somber, naargeestig, getroffen, bezocht.

Omdat Lake Wobegon niet ver onder de grens met het tweetalige Canada ligt, heeft het ook een Franse naam. Onder verwijzing naar Lac Majeur staat het neerslachtige oord ook bekend als Lac Malheur.

—

Robert-Henk Zuidinga (1949) studeerde Nederlandse en Engelse Moderne Letterkunde aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam. Hij schrijft over literatuur, taal- en bij uitzondering – over film.

De drie delen Dit staat er bevatten de, volgens zijn eigen omschrijving, journalistieke nalatenschap van Zuidinga. De boeken zijn in eigen beheer uitgegeven. Belangstelling? Stuur een berichtje naar: info@rozenbergquarterly.com– wij sturen uw bericht door naar de auteur.

Dit staat er 1. Columns over taal en literatuur. Haarlem 2016. ISBN 9789492563040

Dit staat er II, Artikelen en interviews over literatuur. Haarlem 2017. ISBN 9789492563248

Dit staat er III. Bijnamen en Nederlied. Buitenlied en film, Haarlem 2019. ISBN 97894925636637

Elif Shafak – Zo houd je moed in een tijd van verdeeldheid

Hoe kunnen we hoop, vertrouwen en geloof in een betere wereld voeden in een wereld die voelt alsof-ie op instorten staat, waar ontgoocheling en verbijstering heerst en we niet worden gehoord? Door de pandemie maken we nu een betekeniscrisis mee: fundamentele concepten moeten worden geherdefinieerd. De democratie is veel fragieler dan we dachten: ze is een delicaat ecosysteem van checks-and-balances dat voortdurend voeding en verzorging behoeft, aldus Elif Shafak.

Elif Shafak gelooft in de kracht van verhalen om te laten zien hoe democratie, tolerantie en vooruitgang door schrijven kunnen worden gevoed. Zij is geboren in Frankrijk, groeide op in Turkije, Spanje en de Verenigde Staten, en is nu staatsburger van het Verenigd Koninkrijk, maar leeft vooral in ‘Verhalenland’.

Als romanschrijfster voelt ze zich aangetrokken door verhalen en door stiltes. Haar aandacht is vooral gefocust op de ‘periferie’, de gemarginaliseerde, achtergestelde, rechteloze en gecensureerde stemmen. En op taboes: politieke, culturele en gendertaboes, want als we niet luisteren naar afwijkende meningen, stoppen we met leren.

Groepsdenken of sociale mediabubbels voeden en versterken de herhaling. Daarom moeten we blijven bewegen, intellectuele nomaden worden, tijd doorbrengen aan de randen van de samenleving.

De mensen zijn ontgoocheld doordat hun stem niet wordt gehoord, worden geconfronteerd met een politiek systeem dat bestaat uit marketingsteksten, een financiële markt die wordt gedreven door hebzucht en winst, recente gebeurtenissen die niet meer verlopen op de lineaire progressieve manier zoals eerder. Mensen zijn verbijsterd doordat kunstmatige intelligentie en data steeds meer invloed krijgen, zonder dat gewacht wordt totdat het menselijk verstand het kan bevatten. Wat rest is een grote leegte, een onzeker bestaan en een onbekend en onvoorspelbaar begin, waar we helemaal alleen zijn, zonder dat we deel uit maken van een collectief. We zijn ongerust over de toestand van de wereld, en onze plaats daarin, of juist gebrek aan een eigen plaats. We hebben een voortdurende onrust, een existentiële angst, we zijn kwetsbaar. We zijn bezorgd en boos. Hoe kunnen we die individuele en collectieve woede omzetten in een positieve kracht en betrokken zijn? En niet apathisch zijn waardoor we geïsoleerd raken.

Het staat voor Elif Shafak vast dat we niet kunnen terugkeren naar de situatie van voor de pandemie. We hebben de keuze tussen het nationalisme, de ‘eigen volk eerst’-benadering of de weg naar internationale communicatie en samenwerking. De keuze is afhankelijk van economische en politieke factoren, maar ook van het debat over identiteit. Hoe we onze identiteit benaderen zal onze volgende stappen bepalen, aldus Shafak. Zij definieert zichzelf als een wereldburger, een universele ziel, burger van de hele mensheid. We moeten allemaal geëngageerde, betrokken burgers worden. Verhalen kunnen ons daarbij helpen, ze leveren een genuanceerder, reflectievere manier om te beschouwen, ervaren, voelen en herinneren. Ze geven inzicht in de complexiteit en rijkdom van identiteiten, en van de schade die we aanrichten als we die proberen te reduceren tot één enkel definiërend kenmerk. Verhalen hebben een herscheppende kracht om ‘mensen samen te brengen, onze cognitieve horizon te verbreden, en langzaam maar zeker meer empathie en wijsheid te ontwikkelen’.

Elif Shafak – Zo houd je moed in een tijd van verdeeldheid. Uitgeverij Nieuw Amsterdam, 2020. 96 pag. ISBN9789046828151

Elif Shafak schrijft in het Engels en Turks. Haar werk is in vijftig talen vertaald en won diverse internationale prijzen.

Elif Shafak – The revolutionary power of diverse thought

“From populist demagogues, we will learn the indispensability of democracy,” says novelist Elif Shafak. “From isolationists, we will learn the need for global solidarity. And from tribalists, we will learn the beauty of cosmopolitanism” A native of Turkey, Shafak has experienced firsthand the devastation that a loss of diversity can bring — and she knows the revolutionary power of plurality in response to authoritarianism. In this passionate, personal talk, she reminds us that there are no binaries, in politics, emotions and our identities. “One should never, ever remain silent for fear of complexity,” Shafak says.

Check out more TED Talks: http://www.ted.com

Linda Bouws – St. Metropool Internationale Kunstprojecten

‘Limits’ Of Imagining The Pandemic Present

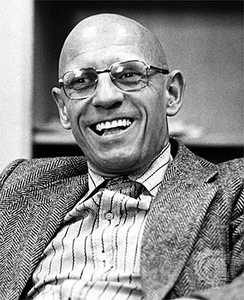

In 1984, Michel Foucault, the French historian (or) philosopher, associated with the structuralist (or) post-structuralist movement, extensively commented [i] on the German Philosopher Immanuel Kant’s ‘Was ist Aufklarung?’ (What is Enlightenment?). Thus, two hundred years hence, Foucault knocked at the limits of moments we live through. For him, Kant is responding in the Berlinische Monatsschrift (Berlin monthly, 1784- November), a late enlightenment mouthpiece, on what should be the attitude to present.

The moment we live in was, for Kant, neither a distinct era, not a transition, but rather a grand exit (Ausgang). For Kant majority of human beings, in the time he wrote in (1700s end or 1800s beginning as the case may be), carried on their everyday life with the church and monarchy setting the rhythms. The autonomy to break the rhythm or to think about the present, and thus make the exit, was difficult then, as it is now. For Foucault Kant was to work on the ‘limits’ of the rhythm and the everyday in order to ‘Ausgang’ and reflect on what he was part of.

With the coordinates of daily rhythms overwhelmingly set by the virus and its trajectories, it has become even tougher to separate ourselves from the contingent contexts we are thrown into everyday. The possibility of thinking separate from the frames we are set against, and reflecting on our ‘makes’, will determine not only how we reflect on the times we live in, but also the way we live out.

People across space and time have transformed to cyborgs – the sciences; technological artifacts; institutional orders; as well as disseminations of knowledge literally imbricate lived lives. Risk societies, urban informalities, everyday precarities, techno-social deployments, or surveillance and pastoral orders have scaled our skins and rewired our bodily rhythms. The cyborg identities in their everyday relationship with other cyborgs, with differential make-ups determine the truth orders that govern.

Foucault comes back to haunt the ‘pandemic orders in the making’ prompting an engagement with the limits. Nothing short of a critical ontology of the cyborgs we are, deployed and networked across space and time, by the political every day, can achieve this. Only this can translate into a possibility or impossibility to imagine the limits that are imposed on us by the political systems, exaggerated by the pandemic.

The possibility of knocking at the limits for instance, might come at best as a tragic reflection during the physical ejection of the urban migrant labourer in India from the metropolis. This is not quite an exit and neither does one see the space or time to reflect on the exploitative order that had appropriated him/her along with millions of others as urban cyborgs. A Lebanese Druze leader who has seen the end of a world war, been through a three month war, or the civil wars; still might only see at best an end of the world because the pandemic has only added on to the noise of everyday violence and earth shattering explosions. The fortified corona shelters that the bus bays have transformed into in a hyper vigilant South Korea or a health care regime that fell apart on the corporate altars in the United States also differentially reduce the space of reflection or eventual exit. A self righteous regime like the one in Brazil that would rather bank on military men than people of science; or the celebrations of self sufficiency (atmanirbhar in the Indian state context) when possibilities of social welfare gets precluded; also talk of the times that give no space for exit-thoughts or possibilities for reflection.

In order to critically reflect on the pandemic everyday and eventually for life to live itself out, there is no other way than exposing the conflicts and contradictions inherent to the orders people live in. There is no other way than to reflect on the ‘fixes’ put forward as part of the ‘presents’. Michel Foucault prompts us to knock at the limits once again. The task for the more privileged in places that still maintain social contracts with populations is to think with Foucauldian ‘dispositives’. These are the institutional, administrative, and knowledge structures that both maintain the systems in place and the homeostasis of the cyborg selves we all are. It is only by thinking through the links between practices, and institutional techniques deployed way before pandemics, but enhanced and perpetuated by the virus; that the cyborgs can get deconstructed across places readying for a political present that is yet to be lived into.

Note

[i] What is Enlightenment? in Rabinow (P.), ed., The Foucault Reader, New York, Pantheon Books, 1984:32-50.

Mathew A Varghese, SIRP, Mahatma Gandhi University [Previously Researcher at University of Bergen/ UKZN]

Ardhakathanak: A Commoner’s Discovery Of The Mughal Milieu

Abstract

The Ardhakathanak by Banarasidas is often considered the first autobiography in Hindi. Completed in the year 1641, the book provides us with a commoner’s understanding of the Mughal world. Often subjected an imperial bias, the book is a wildly neglected source of history. The study attempts to highlight various societal norms and ethics as evidenced by the Ardhakathanak. It undertakes a thematic division in understanding medieval Indian society, focusing on merchant practices, societal norms and Jain religion. Various aspects of a middle class man’s life are unraveled through the course of this study, including education, business decisions, wealth, family, domesticity, religious assimilation, rationality and self-discovery.

The study also embarks on an analysis of the Varanasiya sect of Jain religion briefly. Finally, emerging trends of individuality are highlighted. The study culminates with a brief account of how underutilized this primary source remains despite obvious merits to it.

Keywords: Banarasidas, Ardhkathanak, autobiography, merchant practices, religious pursuits, cultural history.

1. Introduction

The development of the literary genre of autobiography is a fairly ancient one, with St. Augustine’s autobiographical work ‘Confessions’ written in 399 CE. However, the understanding of the term autobiography to be a form of ‘self life writing’ is a recent phenomenon. The Oxford English Dictionary credits Robert Southy to be the progenitor of autobiography in the year 1809. However we find a reference to autobiography or self-biography being used by William Taylor in the Monthly Review of 1797.[i]The motivations for committing one’s life to writing are often religious in nature, to record stages in an individual’s life by which they lose their own identity to celebrate God’s divine power.[ii] Today, these works have become a prominent source of history and are extensively researched to arrive at a deeper understanding of the period it was written in. The earliest known biographical work that was produced in India is the Harshacharita written by Banabhatta in the 7 th century CE. However, truly autobiographical accounts only appear in India with the advent of Mughals. Among these, Baburnama was the earliest, and records Babur’s life between 1483 to 1530.[iii] The autobiographies written during this period were meant to preserve a person’s family history and good deeds for posterity. Thus, the representation of the subject is in light of the reader’s judgement. Therefore, we may conclude that these writings often lack a humanizing touch that can relate the subject to the reader.

One such piece in the ocean of Mughal writings is Banarasidas’s Ardhakathanak. It was first discovered by Nagari Pracharini Sabha and published by Dr. Mataprasad Gupta in 1943.[iv]

Banarasidas was a Jain merchant who lived during the Mughal Era in India. The title of his autobiography translates to ‘half a tale’. The book was completed in the winter of 1641 in the imperial capital of Agra, when Banarasi was 55 years of age. In Jain philosophy, a full life is considered to be of one hundred and ten years. Thus, the title of Banarasi’s book ‘Half a Tale.’ Although, the tale began to be the story of half a life, Banarasi met his demise only two years after the completion of his book, implying that the story covered his entire life. Written in the language of the Indian heartland, Braj Bhasha. Ardhakathanak is considered to be the first autobiography in Hindi.[v] Much to the contrary to other Mughal works, Banarasidas’s tone throughout the book is that of unabashed candor. Over the course of the book, Banarasi establishes a rapport with the reader and slowly but surely becomes a friend. By the time, we reach Banarasi’s close of life, a feeling of a long and fruitful companionship lingers on with the reader. We know Banarasi’s secrets, sorrows and soaring moments. Unlike other autobiographical works of the contemporary period the emphasis is not on making a perfect man devoid of any flaws, fit to govern the territory of India, but to lay bare before the reader the heart and soul of subject, good or bad.

It is evident from the content of the book and style of writing that Banarasi did not expect his autobiography to be read nearly 400 years later. In fact, there was an understanding that it would only be read by limited audience of friends and kinsmen.[vi] In Banarasi’s own words, the only reason he ventured into the business of recording his life, is ‘let me tell you all my story’.

A Jain from the noble Shrimal family,

That prince among men, that man called Banarasi,

He thought to himself, let me tell my story to all [vii]

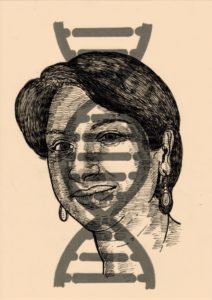

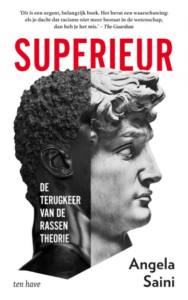

Angela Saini – Superieur. De terugkeer van de Rassentheorie

Superieur van de wetenschapsjournalist Angela Saini is een verslag van het uitgebreide onderzoek naar de biologische feiten rondom het begrip ras.

Bestaat er een verband tussen ras en IQ? Welk ras is het beste? Zijn wij één mensensoort of niet? Wat kan het moderne wetenschappelijke bewijsmateriaal ons echt vertellen over de menselijke verschillen, en wat betekenen die vervolgens?

Deze vragen zijn allerminst gedateerd. De rassentheorie beleeft een zorgwekkende comeback, in wetenschap en politiek. Angela Saini onderzoekt in Superieur pseudowetenschappelijk beweringen en theorieën over ras, en toont aan waarom ze onhoudbaar zijn. Angela Saini komt tot de conclusie dat de biologie deze vraag niet kan beantwoorden. Als we de betekenis van ras willen begrijpen, moeten wij begrijpen hoe macht werkt. Een onderzoek van de Verlichting via het negentiende-eeuwse imperialisme en de twintigste-eeuwse eugenetica naar de revival van de rassentheorie in de eenentwintigste eeuw.

Saini toont in Superieur aan hoe macht het idee van ras telkens weer opnieuw vormgeeft, hoe macht de wetenschappelijke feiten beïnvloedt. De betekenis houdt verband met de tijd.

Lang hebben witte mensen van Europese afkomst zich aan de top van de machtshiërarchie bevonden en bouwden hun wetenschappelijk verhaal over de menselijke soort rond dit geloof. Maar geen enkele regio of volk heeft recht op een claim op superioriteit.

‘Ras is het tegenargument. Ras komt in de kern van de zaak neer op het geloof dat we van geboorte anders zijn, diep in ons lichaam, misschien zelfs qua karakter en intellect, en in onze uiterlijke verschijning.’ Het is het idee dat bepaalde groepen mensen bepaalde aangeboren kwaliteiten hebben. Ras, gevormd door macht, heeft een eigen kracht verkregen. Witheid werd de zichtbare maatstaf van de menselijke moraliteit. Sinds de Verlichting hadden veel Europese denkers zich verenigd rond het idee dat de mensheid één was, dat we dezelfde gemeenschappelijke vermogens deelden. Ook al was er een rassenhiërarchie, ook al waren er mindere mensen en betere mensen, we waren allemaal nog steeds menselijk. In de volgende eeuw vroeg men zich weer af, of we echt wel tot hetzelfde soort behoorden: want waarom zagen wij er niet hetzelfde uit en gedroegen we ons niet op dezelfde manier? Het is geen toeval dat de moderne ideeën over ras zijn gevormd tijdens de hoogtijdagen van het Europese kolonialisme, toen de machthebbers overtuigd waren van hun eigen superioriteit. In de VS werd dezelfde verwrongen logica gebruikt om de slavernij te rechtvaardigen. En de wetenschap voorzag het racisme van intellectueel gezag.

De rassentheorie heeft zich altijd op het kruispunt van wetenschap en politiek opgehouden, en van wetenschap en economie. Ras was niet alleen een middel om fysieke verschillen te classificeren, het was ook een manier om de menselijke vooruitgang te meten, en om te kunnen oordelen over de capaciteiten en rechten van anderen, aldus Saini. Ook Hitlers ideologie van rassenhygiëne had geen kans van slagen zonder wetenschappers, zij zorgden voor het theoretisch kader en droegen bij aan het klaren van de klus zelf. Degenen wier ideeën het regime goed te pas kwamen werden gepromoot en gevierd.

In 1950 formuleerde UNESCO, vlak na de Tweede Wereldoorlog, zijn eerste verklaring over ras, waarin de eenheid tussen mensen werd benadrukt in een gezamenlijke inspanning om een einde te maken aan wat wordt gezien als het gevolg van een ‘fundamenteel anti-rationeel denksysteem.’ Alle mensen behoren tot dezelfde soort ‘Homo sapiens’. Het grootste deel van de zichtbare diversiteit is cultureel van aard. Een cruciaal moment in de geschiedenis. Racisme was niet langer aanvaardbaar. Wetenschappers en antropologen gingen grotendeels achter UNESCO staan.

We denken dat de verschrikkingen van de Holocaust en eerdere genocides, de slavernij en het kolonialisme tot een andere tijd behoren. Dat eugenetica een vies woord is. Saini definieert eugenetica als is een berekende manier van denken over het menselijk leven; mensen worden gereduceerd tot louter delen van een geheel, die hun ras omlaag- of omhoogtrekken. Bijna alles wat we zijn is al beslist voordat we geboren zijn. Maar er zijn weer nieuw wegen gevonden om raciale verschillen te onderzoeken, en dat sommige rassen iets beter waren dan de andere. Na de Tweede Wereldoorlog hebben intellectuele racisten nieuwe netwerken opgezet met het doel racisme weer respectabel te maken. De eugenetici en rassentheorie waren niet verdwenen met de ondergang van het naziregime. Ras werd herpositioneerd voor de eenentwintigste eeuw. Ze noemt als een van de voorbeelden de Indiase regering, die in 2018 een commissie in het leven had geroepen om de geschiedenis te herschrijven. Een mythische versie van de geschiedenis zou worden gepropageerd waar in Indiase dominante geloof, het hindoeïsme, in het hele Indiase verleden centraal zou worden gesteld.

We denken dat de verschrikkingen van de Holocaust en eerdere genocides, de slavernij en het kolonialisme tot een andere tijd behoren. Dat eugenetica een vies woord is. Saini definieert eugenetica als is een berekende manier van denken over het menselijk leven; mensen worden gereduceerd tot louter delen van een geheel, die hun ras omlaag- of omhoogtrekken. Bijna alles wat we zijn is al beslist voordat we geboren zijn. Maar er zijn weer nieuw wegen gevonden om raciale verschillen te onderzoeken, en dat sommige rassen iets beter waren dan de andere. Na de Tweede Wereldoorlog hebben intellectuele racisten nieuwe netwerken opgezet met het doel racisme weer respectabel te maken. De eugenetici en rassentheorie waren niet verdwenen met de ondergang van het naziregime. Ras werd herpositioneerd voor de eenentwintigste eeuw. Ze noemt als een van de voorbeelden de Indiase regering, die in 2018 een commissie in het leven had geroepen om de geschiedenis te herschrijven. Een mythische versie van de geschiedenis zou worden gepropageerd waar in Indiase dominante geloof, het hindoeïsme, in het hele Indiase verleden centraal zou worden gesteld.

De hindoe-superioriteit zou sommige Indiërs de kans bieden hun zelfrespect terug te winnen, collectieve trots te laten gelden, en een nieuw gevoel van nationale identiteit bouwen.

We blijven steeds maar terugkomen op ras omdat we er vertrouwd mee zijn. Onze moderne ideeën over ras zijn nauw verbonden met hoe we eruitzien. In biologische termen lijken echter de verschillen niet verder te gaan dan de huid. Het is een vergissing te denken dat de interne verschillen even groot zijn als de externe verschillen lijken. De opkomst van nationalisme en racisme heeft velen van ons verrast. Identiteitspolitiek heeft velen in de greep. Het doel is hetzelfde: het benadrukken van de verschillen ten bate van politiek gewin.

Zij doet geen beroep een gedeelde menselijkheid. Alles om maar ‘superieur’ te zijn.

Angela Saini – Superieur. De terugkeer van de Rassentheorie. Uitgeverij Ten Have, Amsterdam, 2020. ISBN 9789025907174

Angela Saini is wetenschapsjournalist voor BBC Radio. Haar werk is onder andere gepubliceerd in New Scientist en The Economist.

Eerder verscheen bij Uitgeverij Ten Have Ondergeschikt: Hoe kennis over vrouwen ons misleidt en wat we daaraan kunnen doen.

Linda Bouws – St. Metropool Internationale Kunstprojecten