Where Did Vladimir Putin’s Dream Of A ‘Russian World’ Come From?

Source: Independent Media Institute

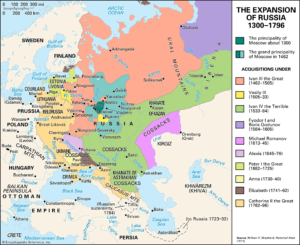

04-15-2024 ~ Russian President Vladimir Putin justified the 2022 invasion of Ukraine by asserting the existence of a singular “Russian world” that needs protection and reunification. He set aside the secular socialist ideological rationales that the Soviet Union used to justify its expansion favoring the Tsarist Russia, rooted in religion and culture. But the history of political orders in the northern European forest zone, which stretches back 1,200 years, is not one of a unified Russian world.

Instead, there were a series of competing orders with rival power centers in Kyiv, Vilnius, and Moscow as well as powerful nomadic steppe polities like those of the Khazar Khaganate, the Mongol Golden Horde, and the Crimean Khanate to the south. Only at the end of the 18th century would they all be forcibly annexed into a single state by Tsarist Russia’s Romanov dynasty. That unified state continued under its Soviet Union successor until it dissolved into 12 independent countries in 1991.

Ukraine and Lithuania in particular had been the centers of their own imperial polities with histories older than Russia itself and were instrumental in creating the Russian culture Putin is now so keen on defending. They achieved this in ways that did not require the protection of an autocrat.

Empires in The Forest Zone

The forest zone spanning the Dniester River in the west and the Volga River in the east historically constituted a vast (more than 2 million square kilometers) but sparsely populated region. It would become the home of three long-lived empires: Kievan Rus’ (862-1242), the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (1251-1795), and the Grand Duchy (later Tsardom) of Muscovy (1283-1721). The surplus wealth that supported these empires came from international transit trade and the export of high-value furs, wax, honey, and slaves, often supplemented by raiding. After expanding beyond its forest zone home, Tsarist Russia declared itself the Russian Empire in 1721 during the reign of Peter the Great (1682-1725), but it took the rest of the century for it to gain control over its neighbors to the south and west, which was achieved during the reign of Catherine the Great (1762-1796).

States of any kind, let alone empires, were absent from the northern forest zone before the 9th century because it was then inhabited only by small and dispersed communities with little urbanization or political centralization. Engaged in subsistence farming, foraging, hunting, and animal husbandry, these communities interacted only with others like themselves or with foreign traders using its rivers to pass through the region. Dense forests and extensive marshlands presented serious obstacles to potential invaders, which were already few because the region had no precious metals to plunder or towns to occupy. This changed when the forest zone was drawn into the high-value commercial network that exchanged a flood of silver coins for furs and slaves, which were traded through a series of intermediaries. The demand for these goods and the silver to pay for them lay in the lands of the distant Islamic Caliphate and the Byzantine Empire, but it was the nomadic Khazar Khaganate (650-850), rulers of the entire steppe zone to the south, who dominated the trade routes. The Khazars exploited that position by projecting their power north into the forest zone where they imposed tribute payments in furs or silver on the communities residing there, creating a class of wealthy local leaders living in towns who were responsible for collecting the payments. They also established trading emporiums on the Volga River that attracted foreign merchants who paid a 10 percent transit tax on the goods they took in or out of the Khazar territory.

Kievan Rus’

The flow of silver resulting from the fur trade attracted the attention of Scandinavian maritime merchant/warrior groups known as the Varangians or Rus’, whose shallow draft boats were easily portaged from one watershed to another. Initially seeking only local trading opportunities, they established their political authority in the north but soon expanded southward through the Dnieper and Volga river systems to reach the Black and Caspian seas where they engaged in raiding and trading. The Varangians replaced the Khazars as the dominant power in the forest region in the 860s. By the 880s, they had moved their center south to Kyiv where they established an empire, Kievan Rus’, which encompassed 2 million square kilometers by the early 11th century. It was an empire that lasted almost four centuries and ended only after the Mongols conquered the entire region and destroyed Kyiv in 1240.

Although Kievan Rus’ is seen as the foundation of later Russian culture, it did not assume its classic form until a century and a half after it was established when Vladimir the Great (r. 980-1015), a pagan polytheist, converted to Eastern Orthodox Christianity in 988 and made it the state religion after marrying a Byzantine princess. He was also responsible for turning Kyiv into a true city with a population of around 40,000 people, erecting Byzantine-style churches there and supporting trade. It was a multiethnic state that developed its own common culture by drawing on a variety of sources. Eastern Orthodox Christianity brought with it a tradition of literacy and the Cyrillic alphabet, a hierarchical clerical establishment, and a Byzantine tradition of governance where state authority was based on laws and institutions. Rus’ rulers also respected the authority of existing Slavic political institutions at the local level that included decision-making councils in towns and regions (veche), Indigenous local rulers (kniaz), and a class of aristocratic military commanders (voevoda). Although only the direct descendants of the Rus’ founder Rurik could hold the top position of the grand prince and other high ranks, this ruling lineage intermarried with its Slavic subjects (Vladimir’s mother was one of the offsprings of this kind of intermarriage), and eventually adopted their language.

Perhaps most significantly, Kievan grand princes did not wield absolute power. After the empire reached its zenith under Vladimir and his son Yaroslav the Wise (r. 1016–1054), constant wars of succession among the Rurikid elite weakened the central government to such an extent that by the mid-12th century it had devolved into a looser federation of autonomous regional polities (with Kyiv, Novgorod, and Suzdalia being the most prominent) whose leaders agreed among themselves on who would become the grand prince. The government survived because it was a jellyfish-like state that absorbed enough resources to sustain itself without requiring either a strong imperial center or autocratic leadership, and where no single part was critical to the survival of the whole.

Lacking a brain, jellyfish depend on a distributed neural network composed of integrated nodes that together create a highly responsive nervous system. As a result, jellyfish can survive the loss of body parts and regenerate them quickly. Similarly, Kiev and its grand prince was only the biggest node in a system of nodes rather than an exclusive one. And because jellyfish regeneration is designed to restore damaged symmetry rather than simply replace the lost parts, a jellyfish cut in half becomes two new jellyfish as each half regenerates what is missing. Following this pattern as well, two rival empires eventually emerged in the lands of the old Kievan Rus’ after the Mongol occupation finally ended: the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the west and the Grand Duchy of Muscovy in the east. Read more

A Class Analysis Of The Trump-Biden Rerun

Richard D. Wolff

04-15-2024 ~ By “class system” we mean the basic workplace organizations—the human relationships or “social relations”—that accomplish the production and distribution of goods and services. Some examples include the master/slave, communal village, and lord/serf organizations. Another example, the distinctive capitalist class system, entails the employer/employee organization. In the United States and in much of the world, it is now the dominant class system. Employers—a tiny minority of the population—direct and control the enterprises and employees that produce and distribute goods and services. Employers buy the labor power of employees—the population’s vast majority—and set it to work in their enterprises. Each enterprise’s output belongs to its employer who decides whether to sell it, sets the price, and receives and distributes the resulting revenue.

In the United States, the employee class is badly split ideologically and politically. Most employees have probably stayed connected—with declining enthusiasm or commitment—to the Democratic Party. A sizable and growing minority within the class has some hope in Trump. Many have lost interest and participated less in electoral politics. Perhaps the most splintered are various “progressive” or “left” employees: some in the progressive wing of the Democratic Party, some in various socialist, Green, independent, and related small parties, and some even drawn hesitatingly to Trump. Left-leaning employees were perhaps more likely to join and activate social movements (ecological, anti-racist, anti-sexist, and anti-war) rather than electoral campaigns.

The U.S. employee class broadly feels victimized by the last half-century’s neoliberal globalization. Waves of manufacturing (and also service) job exports, coupled with waves of automation (computers, robots, and now artificial intelligence), have mostly brought that class bad news. Loss of jobs, income, and job security, diminished future work prospects, and reduced social standing are chief among them. In contrast, the extraordinary profits that drove employers’ export and technology decisions accrued to them. Resulting redistributions of wealth and income likewise favored employers. Employees increasingly watched and felt a parallel social redistribution of political power and cultural riches moving beyond their reach.

Employees’ class feelings were well grounded in U.S. history. The post-1945 development of U.S. capitalism smashed the extraordinary employee class unity that had been formed during the Great Depression of the 1930s. After the 1929 economic crash and the 1932 election, a reform-minded “New Deal” coalition of labor union leaders and strong socialist and communist parties gathered supportively around the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration that governed until 1945. That coalition won huge, historically unprecedented gains for the employee class including Social Security, unemployment compensation, the first federal minimum wage, and a large public jobs program. It built an immense following for the Democratic Party in the employee class.

As World War II ended in 1945, every other major capitalist economy (the UK, Germany, Japan, France, and Russia) was badly damaged. In sharp contrast, the war had strengthened U.S. capitalism. It reconstructed global capitalism and centered it around U.S. exports, capital investments, and the dollar as world currency. A new, distinctly American empire emerged, stressing informal imperialism, or “neo-colonialism,” against the formal, older imperialisms of Europe and Japan. The United States secured its new empire with an unprecedented global military program and presence. Private investment plus government spending on both the military and popular public services marked a transition from the Depression and war (with its rationing of consumer goods) to a dramatically different relative prosperity from the later 1940s to the 1970s.

Cold War ideology clothed post-1945 policies at home and abroad. Thus the government’s mission globally was to spread democracy and defeat godless socialism. That mission justified both increasingly heavy military spending and McCarthyism’s effective destruction of socialist, communist, and labor organizations. The Cold War atmosphere facilitated undoing and then reversing the Great Depression’s leftward surge of U.S. politics. Purging the left within unions plus the relentless demonization of left parties and social movements as foreign-based communist projects split the New Deal coalition. It separated left organizations from social movements and both of them from the employee class as a whole. Read more

The Decline Of Extreme Poverty

Saurav Sarkar – Source: Globetrotter Media

04-15-2024 ~ One of the foremost accomplishments of the industrial age is the “immense progress against extreme poverty.”

“Extreme poverty” is defined by the World Bank as a person living on less than $2.15 per day using 2017 prices. This figure has seen a sharp decline over the last two centuries—from almost 80 percent of the world’s population living in extreme poverty in 1820 to only about 10 percent living in these conditions by 2019. This is all the more astounding given that the population of the world is about 750 percent higher.

The causes of economic progress are clear. The laborers of past generations around the world—often against their will—gave us industrial revolutions. These industrial economies rely on, and generate, machinery, technology, and other capital goods. These are then deployed in an economy that requires less sacrifice of human labor and can generate more goods and services for the populations of the world, even as populations continue to grow.

Some ideologies, such as socialism, were most effective in fighting extreme poverty. Socialism is defined here as the state control of a national economy with an eye toward the welfare of the masses. Socialist regimes serve to counter and remove extreme poverty. Two regions illustrate this point well and account for billions of people who moved out of extreme poverty in the last century—all of them influenced by or under the rubric of socialism.

In the USSR and Eastern Europe, extreme poverty declined from about 60 percent in 1930 to almost zero in 1970. In China too, extreme poverty has been eliminated to virtually zero today, though there are debates over exactly what produced those gains. Some argue that these gains are the product of capitalist reforms; but even if this were the case, those reforms took advantage of the groundwork laid by the post-1949 socialist economy.

There is also a certain logic to why socialist economies in the 20th century were able to eventually generate massive gains for those at the very bottom of their societies. While not the only ideology that can do so, socialism is particularly good at the kind of state control and support of economies that is required for successful industrialization. Moreover, because socialism sets itself up to be politically evaluated by what it delivers to those at the very bottom, the politics of socialist countries tend to moderate some of the inequality that comes with industrialization in a capitalist world. This makes it markedly different from other varieties of state control like colonialism, imperialism, state capitalism, and fascism.

Socialism’s existence also seems to have pushed forward reductions in poverty in the capitalist sections of the world. The presence of the Soviet Union and internal left movements across the capitalist world put pressure on capitalist regimes to offer more goods and services to their working classes and underclasses. This is evident from several instances throughout the world, such as the role of communists in fighting for civil rights for Black people in the United States.

While there might have been an immense reduction in extreme poverty over the decades, a series of setbacks brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic and various ongoing wars across the world have recently made a dire situation worse for those already struggling to make ends meet. According to a 2022 World Bank report, “the pandemic pushed about 70 million people into extreme poverty in 2020, the largest one-year increase since global poverty monitoring began in 1990. As a result, an estimated 719 million people subsisted on less than $2.15 a day by the end of 2020.”

This means that the world is “unlikely” to achieve the UN target of eradicating extreme poverty by 2030. Consider what it looks like to live on less than $2.15 per day. It means that you cannot even “afford a tiny space to live, some minimum heating capacity, and food” that will prevent “malnutrition.” As we struggle to meet our goals, the majority of the world population has been forced to live on under $10 a day, while 1.5 percent of the population receives $100 a day or more.

Moreover, a racial analysis is also important to include given that extreme poverty is increasingly concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa and parts of South Asia. Poorer countries (which are home to the vast majority of Black and brown populations) are “encouraged” to produce the cheapest and simplest goods for trade rather than developing self-sustaining economies or upgrading their economies and workforces. In fact, they are often pushed to destroy existing economies.

The final rub in any discussion of poverty is that the preexisting solutions to it— industrialization—may not be feasible with the limitations of a warming planet. If sub-Saharan Africa needs to industrialize to eliminate extreme poverty in that region, who will pay for that carbon footprint? Presumably, the countries of the Global North that have the most historical carbon debt ought to, but it is hard to imagine a world in which they will voluntarily do so. After all, they have yet to make reparations for the stolen labor with which their wealth was built in the first place.

By Saurav Sarkar

Author Bio: This article was produced by Globetrotter.

Saurav Sarkar is a freelance movement writer, editor, and activist living in Long Island, New York. Follow them on Twitter @sauravthewriter and at sauravsarkar.com.

Source: Globetrotter

Why Culture Is Not The Only Tool For Defining Homo Sapiens In Relation To Other Hominins

Deborah Barsky

04-12-2004 ~ We need a broad comparative lens to produce useful explanations and narratives of our origins across time.

While the circumstances that led to the emergence of anatomically modern humans (AMH) remain a topic of debate, the species-centric idea that modern humans inevitably came to dominate the world because they were culturally and behaviorally superior to other hominins is still largely accepted. The global spread of Homo sapiens was often hypothesized to have taken place as a rapid takeover linked mainly to two factors: technological supremacy and unmatched complex symbolic communication. These factors combined to define the concept of “modern behavior” that was initially allocated exclusively to H. sapiens.

Up until the 1990s, and even into the early 21st century, many assumed that the demographic success experienced by H. sapiens was consequential to these two distinctive attributes. As a result, humans “behaving in a modern way” experienced unprecedented demographic success, spreading out of their African homeland and “colonizing” Europe and Asia. Following this, interpopulation contacts multiplied, operating as a stimulus for a cumulative culture that climaxed in the impressive technological and artistic feats, which defined the European Upper Paleolithic. Establishing a link between increased population density and greater innovation offered an explanation for how H. sapiens replaced the Neandertals in Eurasia and achieved superiority to become the last survivor of the genus Homo.

The exodus of modern humans from Africa was often depicted by a map of the Old World showing an arrow pointing northward out of the African continent and then splitting into two smaller arrows: one directed toward the west, into Europe, and the other toward the east, into Asia. As the story goes, AMHs continued their progression thanks to their advanced technological and cerebral capacities (and their presumed thirst for exploration), eventually reaching the Americas by way of land bridges exposed toward the end of the last major glacial event, sometime after 20,000 years ago. Curiosity and innovation were put forward as the faculties that would eventually allow them to master seafaring, and to occupy even the most isolated territories of Oceania.

It was proposed that early modern humans took the most likely land route out of Africa through the Levantine corridor, eventually encountering and “replacing” the Neandertal peoples that had been thriving in these lands over many millennia. There has been much debate about the dating of this event and whether it took place in multiple phases (or waves) or as a single episode. The timing of the incursion of H. sapiens into Western Europe was estimated at around 40,000 years ago; a period roughly concurrent with the disappearance of the Neandertal peoples.

This scenario also matched the chrono-cultural sequence for the European Upper Paleolithic as that was defined since the late 19th century from eponymous French archeological sites, namely: Aurignacian (from Aurignac), Gravettian (from La Gravette), Solutrean (from Solutré), and Magdalenian(from la Madeleine). Taking advantage of the stratigraphic sequences provided by these key sites that contained rich artifact records, prehistorians chronicled and defined the typological features that still serve to distinguish each of the Upper Paleolithic cultures. Progressively acknowledged as a reality attributed to modern humans, this evolutionary sequencing was extrapolated over much of Eurasia, where it fits more or less snugly with the archeological realities of each region.

Each of these cultural complexes denotes a geographically and chronologically constrained cultural unit that is formally defined by a specific set of artifacts (tools, structures, art, etc.). In turn, these remnants provide us with information about the behaviors and lifestyles of the peoples that made and used them. The Aurignacian cultural complex that appeared approximately 40,000 years ago (presumably in Eastern Europe) heralded the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic period that ended with the disappearance of the last Magdalenian peoples some 30,000 years later—at the beginning of the interglacial phase marking the onset of the (actual) Holocene epoch.

The conditions under which the transition from the Middle to the Upper Paleolithic took place in Eurasia remains a topic of hot debate. Some argue that the chronological situation and features of Châtelperronian toolkits identified in parts of France and Spain and the Uluzzian culture in Italy, should be considered intermediate between the Middle and Upper Paleolithic, while for others, it remains unclear whether Neandertals or modern humans were the authors of these assemblages. This is not unusual, since the thresholds separating the most significant phases marking cultural change in the nearly 3 million-year-long Paleolithic record are mostly invisible in the archeological register, where time has masked the subtleties of their nature, making them seem to appear abruptly. Read more

Armenia’s Escape From Isolation Lies Through Georgia

John P. Ruehl Independent Media Institute

04-11-2024 ~ Surrounded to its east and west by hostile neighbors and devoid of allies, Armenia’s geopolitical situation faces severe challenges. A growing partnership with Georgia could help the small, landlocked country to expand its options.

For the second time this year, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan met with his Georgian counterpart on March 24. The meeting, held in Armenia’s capital of Yerevan, saw both leaders reaffirming their growing commitment to enhancing already positive relations. Armenia has placed greater emphasis on recognizing the untapped potential of Georgia in recent years, given Yerevan’s increasingly challenging geopolitical circumstances.

Armenia underwent a significant foreign policy shift away from Russia and towards Europe following the 2018 Velvet Revolution and the election of Pashinyan. However, this shift exposed the country’s security vulnerabilities. In 2020, neighboring Azerbaijan decisively defeated Armenian forces defending the Armenian-majority enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh in 2020, followed by subsequent clashes in 2022 and 2023, leading to the dissolution of the enclave. With its current military advantage, Azerbaijan’s forces are instigating border confrontations on Armenian territory and demanding the return of several small Azerbaijani villages in Armenia.

Azerbaijan has refused to participate in EU or U.S.-initiated peace talks in recent months. Meanwhile, Russia has largely ignored Armenia’s plight amid its struggles in Ukraine to punish Yerevan. Instead, Russia has sought closer ties with Azerbaijan, as evidenced by Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev’s visit to Moscow immediately after Russia recognized the independence of the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics in Ukraine. During the 2022 visit, pledges were made to increase military and diplomatic cooperation between Russia and Azerbaijan and to resolve remaining border issues.

Russia maintains a military base in Armenia, controls parts of its border, and wields significant economic influence in the country. Despite this, Armenia opposes Moscow’s mediation in peace talks and continues to seek closer ties to the West. While Western countries have shown sympathy to Armenia’s plight and criticized Azerbaijan, Armenia has received little tangible assistance. Azerbaijan’s emergence as a vital transport corridor and source of natural resources, combined with the limited ability of the West to project power in the Caucasus region, has prevented the West from taking harsher measures against it.

The small American military force sent for a joint military exercise with Armenia, for example, concluded on the day of the 2023 war which marked the end of Nagorno-Karabakh’s existence. Despite its presence, the force was powerless to dissuade Azerbaijan. Additionally, while U.S. President Joe Biden initially declared his intention to withhold U.S. military aid to Azerbaijan due to its actions against Armenia in 2020, he later reversed this decision—a pattern consistent with previous U.S. administrations since the early 1990s. The decision is currently pending ratification despite domestic opposition in the U.S. Read more

The Myth That India’s Freedom Was Won Nonviolently Is Holding Back Progress

Justin Podur – Source: York University – podur.org

04-10-2024 ~ Some struggles can be kept nonviolent, but decolonization never has been—certainly not in India.

If there is a single false claim to “nonviolent” struggle that has most powerfully captured the imagination of the world, it is the claim that India, under Gandhi’s leadership, defeated the mighty British Empire and won her independence through the nonviolent method.

India’s independence struggle was a process replete with violence. The nonviolent myth was imposed afterward. It is time to get back to reality. Using recent works on the role of violence in the Indian freedom struggle, it’s possible to compile a chronology of the independence movement in which armed struggle played a decisive role. Some of these sources: Palagummi Sainath’s The Last Heroes, Kama Maclean’s A Revolutionary History of Interwar India, Durba Ghosh’s Gentlemanly Terrorists, Pramod Kapoor’s 1946 Royal Indian Navy Mutiny: Last War of Independence, Vijay Prashad’s edited book, The 1921 Uprising in Malabar, and Anita Anand’s The Patient Assassin.

Nonviolence could never defeat a colonial power that had conquered the subcontinent through nearly unimaginable levels of violence. India was conquered step by step by the British East India Company in a series of wars. While the British East India Company had incorporated in 1599, the tide turned against India’s independence in 1757 at the battle of Plassey. A century of encroaching Company rule followed—covered in William Dalrymple’s book The Anarchy—with Company policy and enforced famines murdering tens of millions of people.

In 1857, Indian soldiers working for the Company rose up with some of the few remaining independent Indian rulers who had not yet been dispossessed—to try to oust the British. In response, the British murdered an estimated (by Amaresh Mishra, in the book War of Civilisations) 10 million people.

The British government took over from the Company and proceeded to rule India directly for another 90 years.

From 1757 to 1947, in addition to the ten million killed in the 1857 war alone, another 30-plus million were killed in enforced famines, per figures presented by Indian politician Shashi Tharoor in the 2016 book Inglorious Empire: What the British Did to India.

A 2022 study estimated another 100 million excess deaths in India due to British imperialism from 1880 to 1920 alone. Doctors like Mubin Syed believe that these famines were so great and over such a long period of time that they exerted selective pressure on the genes of South Asian populations, increasing their risk of diabetes, heart disease, and other diseases that arise when abundant calories are available because South Asian bodies have become famine-adapted.

By the end, the independence struggle against the British included all of the methods characteristic of armed struggle: clandestine organization, punishment of collaborators, assassinations, sabotage, attacks on police stations, military mutinies, and even the development of autonomous zones and a parallel government apparatus.

A Chronology of India’s Violent Independence Struggle

In his 2006 article, “India, Armed Struggle in the Independence Movement,” scholar Kunal Chattopadhyay broke the struggle down into a series of phases:

1905-1911: Revolutionary Terrorism. A period of “revolutionary terrorism” started with the assassination of a British official of the Bombay presidency in 1897 by Damodar and Balkrishna Chapekar, who were both hanged. From 1905 to 1907, independence fighters (deemed “terrorists” by the British) attacked railway ticket offices, post offices, and banks, and threw bombs, all to fight the partition of Bengal in 1905. In 1908, Khudiram Bose was executed by the imperialists for “terrorism.”

These “terrorists” of Bengal were a source of great worry to the British. In 1911, the British repealed the partition of Bengal, removing the main grievance of the terrorists. They also passed the Criminal Tribes Act, combining their anxieties over their continued rule with their ever-present racial anxieties. The Home Secretary of the Government of India is quoted in Durba Ghosh’s book Gentlemanly Terrorists:

“There is a serious risk, unless the movement in Bengal is checked, that political dacoits and professional dacoits in other provinces may join hands and that the bad example set by these men in an unwarlike province like Bengal may, if it continues, lead to imitation in provinces inhabited by fighting races where the results would be even more disastrous.” Read more