When Congo Wants To Go To School – The Subject Matter

In the previous chapters, what was actually happening during lessons became dimly visible here and there. In this chapter this will be examined more closely. Learning in a class situation can be approached in many different ways. I assume in any case that a combination of various points of view is needed to achieve a picture of ‘reality’. What was taught? This can be deduced from the content of curricula tested by the commentary in inspection reports. It can also be partially deduced from the subject matter in the textbooks used. How was this taught? This is actually a question of the pedagogical principles the missionaries adhered to: did they talk about this? Did these principles even exist?

What was in the curriculum?

The curricula for subsidised missionary education have already been discussed in chapter two. By and large the period in question can be divided as follows, using the applicable curriculum guides: the period from 1929 to 1949, under the first curriculum (the Brochure Jaune), from 1949 to just after half-way through the 1950s, under the second (and third) curriculum and the second half of the 1950s, in which métropolisation was imposed (and, in principle, the Belgian syllabus should have been implemented). Apart from the fact that the transition between the different periods, especially between the second and third, is not very strictly defined, the first curriculum was noticeably enforced for the majority of the colonial period (taking the previously discussed proposal of 1938 into account). It did not seem worthwhile to analyse the changes in lesson content between the curricula of 1929 and 1948 in detail. After all it is almost certain that there is no general and direct concordance between what was required in the curriculum guides and what was actually taught. The curriculum guides only gave minimal norms, general guidelines and guiding principles. Obviously, it did not include the detailed contents of lessons. The third and final reason was that the curriculum was fragmented in the guide of 1948 through the introduction of the distinction between the normal and ‘selected’ second grade. This made an orderly comparison more difficult. The evolution of the two curricula in the area of subject content will only be touched upon very briefly.

However, it did seem worthwhile to make a summary comparison of colonial and Belgian curricula, especially to try to counter a certain representation. Otherwise it might be assumed too easily that the education in Belgian Congo was no more than a kind of occupational therapy. The researcher and the reader are faced here with a very subtle balancing exercise. On the one hand, the intention is to discover the reality, or at least to try: the ‘how’ and ‘what’ of school reality in the past. On the other hand, it is necessary to articulate what almost everyone will be thinking automatically when reading a story of the period: namely that ‘it wasn’t the way it is now’ and that the attitudes of a number of protagonists, namely the missionaries, were fairly ‘old-fashioned’, even ‘primitive’ or ‘backward’.

Of course such an opinion seems suspiciously similar to remarks made by the missionaries themselves about the Congolese (which partly causes them) but this does not mean they should not be mentioned. Nor should they necessarily be attacked with moral judgements but, on the other hand, they should be interpreted. In the first instance it is of course only human to distance oneself in one way or another from events that happened in other places at other times. We must, of course, avoid falling into an a-historical position but the reaction itself is not an historical aberration, in the sense of ‘very wrong at the time’. After all, in the same way the ideas of the missionaries are not to be considered as thoughts that ‘should not really have been thought’ and should have given rise to moral indignation. The foundations of the stance assumed in the colonial context are, after all, to be found in structures, positions and reactions in the home context of the colonisers. This can also be shown clearly in the context of the curricula. Read more

When Congo Wants To Go To School – Educational Practices

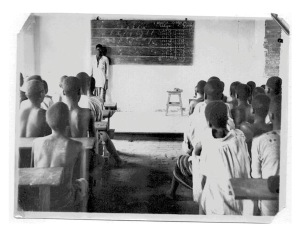

In this chapter the focus shifts slightly to didactic and educational practices, insofar as these can be known. This is used in the meaning of every day interaction between missionaries, moniteurs (teaching assistants) and pupils. The inspection reports give some insight here into what really happened, although in most cases from a distance. Although the reports and letters from inspectors may be said to be perfect examples of the normative, this does not mean that they make it possible to see clearly what practices were criticised and for which practices alternatives were offered. Two contrasts that were discussed earlier appear again and ‘mark’ distinctions between them. The first is the distinction between the centre and periphery, which, in this context coincides with the dichotomy mission school – rural school. In the previous chapters it was obvious that the material situation was very different depending on whether a school was situated at the central mission post school or a bush school. The second contrast between the two types of teachers, missionaries or moniteurs corresponds largely with the mission school – rural school situation. These distinctions are, in fact, situated almost entirely within the context of the central mission school, considering that, almost by definition, no missionaries taught in rural schools.

In this chapter the focus shifts slightly to didactic and educational practices, insofar as these can be known. This is used in the meaning of every day interaction between missionaries, moniteurs (teaching assistants) and pupils. The inspection reports give some insight here into what really happened, although in most cases from a distance. Although the reports and letters from inspectors may be said to be perfect examples of the normative, this does not mean that they make it possible to see clearly what practices were criticised and for which practices alternatives were offered. Two contrasts that were discussed earlier appear again and ‘mark’ distinctions between them. The first is the distinction between the centre and periphery, which, in this context coincides with the dichotomy mission school – rural school. In the previous chapters it was obvious that the material situation was very different depending on whether a school was situated at the central mission post school or a bush school. The second contrast between the two types of teachers, missionaries or moniteurs corresponds largely with the mission school – rural school situation. These distinctions are, in fact, situated almost entirely within the context of the central mission school, considering that, almost by definition, no missionaries taught in rural schools.

However, they do not correspond completely. Ideally, it should be possible to identify three different situations within the context of (Catholic) missionary education: A first situation in which pupils received education without any, or only sporadic, intervention from missionaries. This is what was found in rural schools; a second situation, in which a moniteur gave lessons in a central mission post, near to missionaries but not in their permanent presence; and a third situation in which the missionaries exercised permanent control over what happened in the class or gave lessons themselves. This third situation was, as should already be clear, quite unusual (except in the initial phase of a mission post). In a number of cases one subject was given systematically by missionaries. Usually that was religious education. In other cases one class, and usually the highest one, was entrusted to the care of a missionary. This occurred mostly from necessity because no native teacher could be found who was suitable for the job. In girls education there were, relatively speaking, more female religious who actually taught themselves. This must be explained by the fact that female education was way less developed because of the social context in which Congolese girls functioned and because of the position of the female religious workers themselves.

The organisation of this chapter is not, in fact, along these lines. The available sources were, after all, almost exclusively produced by the missionaries themselves. It also seems to me to be difficult to deal in an even-handed manner with situations in which the missionary staff were absent and to give them, quantitatively speaking, just as much space as the others. For this reason another approach was chosen. It starts from general observations or questions (“topics”). This is probably less structured but at the same time also ‘more honest’ towards the reality studied in the sense that it has been decided beforehand to start from one particular aspect, to collect information about this and to discuss it, but without causing the reality to ‘stop’ at a particular moment. In any event this approach is easier to grasp because in this way we avoid telling a too compartmentalised story, whereby for each of the three proposed hypotheses the same topics would need to be dealt with again and again.

Discipline

1.1. The school rules: theory…

In principle every school had to have school rules: “In every class there hangs a set of rules for the Colony: there is a lot on it, 20 numbers composed by the Father Director of the Colony himself. Get up … attend Holy mass… Work… school… eat… go to sleep… and so forth…“[i] The scope of the rules probably differed strongly according to the place and the congregation that was active there. A very interesting example for the study of classroom reality is the rather comprehensive rulebook of the Brothers of the Christian Schools, created for the Groupe Scolaire in Coquilhatville.[ii] In theory, the Brothers had been given responsibility for the pupils during school time but in practice their reach went further. The rulebook contained a mixture of instructions that was directed at the moniteurs and the pupils. It constitutes a very normative source, to the extent that we can expect it to effectively reflect reality for a large part. The book begins with a list of provisions that applied to the teaching staff. It applied to their behaviour and also to their tasks with respect to the pupils. Among these, a lot of attention is paid to religiously inspired themes. After a few indications for the maître chrétien himself (enough prayer, be punctual, make sure that the timetable is respected), there follows the first chapter “éducation chrétienne“. Reciting the correct number of prayers a day, the use of a rosary, going to mass and confession at set times: it was the task of the teaching staff to make sure that the pupils certainly did these. “Enseignement” was only mentioned in the second section. Here, a number of items were discussed in connection with the teaching method, from which not very much can be deduced about the reality. The teacher must follow the curriculum and make an effort to pass perfect knowledge on to the pupils: “He shall carefully prepare his lessons and give methodical and graduated education. He shall apply himself to cultivating the intelligence of his pupils as well as their memory and language.” Read more

When Congo Wants To Go To School – Part III – Acti Cesa

A few years ago Catherine Coquery-Vidrovitch wrote about the results of the educational system in the Belgian Congo that “(This) in depth work concerning mentalities was started to be felt from 1945. [i] We have tried to approach the issue of the effects of the missionary education from two angles. On the one hand, on the basis of the written testimonies that can be found, from which it is apparent how the Congolese reacted, how they acted and what they thought about that education. Publications in which the opinion of the Congolese pupils and former pupils can be found were sought as contemporary sources. Concrete, extensive and detailed research was carried out into one of those publications, La Voix du Congolais. On the other hand, it is possible to make use of memories. These are preferably the memories of the people themselves. A number of interviews with the Congolese helped complement the very sparse literature available in this regard.

A few years ago Catherine Coquery-Vidrovitch wrote about the results of the educational system in the Belgian Congo that “(This) in depth work concerning mentalities was started to be felt from 1945. [i] We have tried to approach the issue of the effects of the missionary education from two angles. On the one hand, on the basis of the written testimonies that can be found, from which it is apparent how the Congolese reacted, how they acted and what they thought about that education. Publications in which the opinion of the Congolese pupils and former pupils can be found were sought as contemporary sources. Concrete, extensive and detailed research was carried out into one of those publications, La Voix du Congolais. On the other hand, it is possible to make use of memories. These are preferably the memories of the people themselves. A number of interviews with the Congolese helped complement the very sparse literature available in this regard.

When considering this theme, the original boundaries of the research subject were slightly deviated from. The research subject was deviated from as regards the material, as the

interviews are situated both within but also partly outside the mission area of the MSC. The existing research results that were consulted and used also relate to areas outside the Tshuapa region. Moreover, the research subject was deviated from with regard to content due to the conclusion that research into the effects of education is inextricably connected to the “memory” of the colonial period. Consequently, it seemed interesting to us to take the memories of former pupils into account. That has the undeniable advantage that the image drawn may be confronted to a certain extent with the memories of the Congolese.

In the previous four chapters, written material was primarily collected that spoke about the events that took place in and around the school in the mission area of the MSC. The image created as a result is perhaps still not very clear but the outlines may be discerned. Naturally coloured by all the information I collected myself as a researcher and undoubtedly also coloured by the information I did not collect, I did not think it very useful to consider all that material again in a conclusive chapter and to attempt to distil a summarising image from that.

I will therefore restrict my conclusion to an indication of the image drawn and the formulation of a number of considerations regarding the way in which this past is handled and the role this research may hopefully play in it.

NOTE:

[i] Tshimanga, C. (2001). Jeunesse, formation et société au Congo/Kinshasa 1890-1960 . Paris: L’Harmattan. p. 5 (préface). [original quotation in French]

When Congo Wants To Go To School – The Short Term: Reactions

Effects on the colonists: initiation of an African science of education?

Effects on the colonists: initiation of an African science of education?

In 1957 Albert Gille, Director of Education at the Ministry for Colonies, wrote that the biggest problem of education at that time remained the lack of well-trained teachers. He claimed that the quality of the teaching staff remained low and that there would be no improvement over the next few years.[i] There was not much opportunity to climb the social ladder. There were very few signs that the educational principles had changed under the impulse of Buisserets policy, which indeed ‘broke open’ the educational system. In fact, education in the Congo then became ‘metropolised’,[ii] but the changes in the curriculum were not accompanied by a significantly different composition of the body of teachers. The impact of the changes was quantitatively too limited to be able to bring about a general change in the short term. Until after independence, education would still remain almost completely in the hands of the mission congregations.

The early Congolese universities did produce some scientific research on education, but this research did not break out of the familiar straightjacket either. At the University of Lovanium research results and opinions in the field of education were published in the Revue pédagogique, which has already been mentioned. At the Official University Paul Georis was particularly active in the area of educationalism, but the results of his investigations only appeared after independence.[iii] Georis was the head of a so-called “interracial” high school in Stanleyville for four years and studied the possibilities of developing educational theory adapted to African circumstances there. His colleagues did the same in Luluaburg and Lodja. The most important elements that came to the fore in the research on such new educational theories, which he published in 1962 (but had written before independence), were the community life of the Congolese, the uniqueness of Congolese culture and respect for foreign cultures. In addition, the importance of an improvement of the level of education was also emphasised. Georis also referred to the splitting of education into mass- and elite-education. That it was necessary to point out, even in this publication, which was written in rather ‘progressive’ milieus, that “the qualitative equality of the intelligence of the Black and the White can be proven” is telling of the zeitgeist. In that respect the author also argued for a uniformity and equivalence in the primary education system for all levels of the population.

However, there were a number of obstacles in the way of the development towards a balanced educational system. Besides the vast size of the country and – here too – the poor quality of the teaching body, Georis mentioned the Congolese attachment to their ancestral traditions and the influence of magic as primary elements. Generally speaking, he seemed to argue for blending the traditional African values with imported Western ideas, which naturally did not prevent him from arguing within a progressive or developmental paradigm. Despite all his good intentions, he regularly remained bogged down in the model of ‘civilisation versus primitivism’. The “black”, he concluded in his study, could free himself from his neuroses and his complexes. Apparently that was still necessary.

On the other hand, an 1958 editorial contribution in the Revue Pédagogique about the “programmes métropolitains” and the adaptation of education, stated that: “In the Congo, we have for a long time attempted clumsy and timid adaptations, which proved inoperative. Now we are turning away from this path and are increasingly adopting the metropolitan curricula from Belgium, following the example of France, which has applied the French curricula for a long time.” Consequently, at that time, there was some hard thinking going on in both university milieus concerning the direction of education. In both cases questions were being asked aloud about the manner in which things had been done in the past. It is not illogical that in university circles at that time more discerning and detailed analyses were being made. There was a great deal of political activism at that time: in 1956 the manifestos of Conscience Africaine and the ABAKO had already been published and in 1958 the MNC of Lumumba and Ileo was formed; local council elections were also organised in 1958. The predominant attitude, also applicable to the educationalists, was still very expectant, cautious and doubtful.[iv] Even the contribution mentioned above, after initially pleading pro métropolisation, stated that it was very unclear what the Africans really wanted. They longed for Western education, to be able to get Western diplomas, because that was the only way to be recognised as an equal. But at the same time they also wanted something else and the next step would then have to be recovering their own cultural identity. The periodical’s attitude was summed up well in the last sentence of the contribution: “These are the general and imprecise assertions that must nevertheless be taken into account.”

Effects on the colonised: the needle in the haystack

2.1. At a university level

If we want to judge the effects of education, we must necessarily search for the voices of the people involved and those are primarily the Congolese. In the case of the universities and the science of education itself, this voice did not ring out very loudly. The reasons for this are not hard to find: it was too late and there were too few of them. At the University of Lovanium the first seven Congolese students graduated in June 1955 from the first year of a bachelor in Educational Science. Of these only two graduated three years later in June 1958 with a master’s (these were two priests, Michel Karikunzura and Ildephonse Kamiya).[v] In Elisabethville, where the ‘Official’ University operated from 1956, a ‘School for Educational Sciences’ was set up from the beginning. During the academic year 1957-1958 five African students were enrolled in the first year of the bachelor’s degree at the school (there were a total of 17 African students enrolled at the University at that time). In Lovanium there were 110 African students, of which 18 studied educational sciences.[vi] Read more

When Congo Wants To Go To School – The Long Term: Memories

“We arrive, it is as though it is some amusement, the people are standing there, we left for school, my poor father stood on the road until I disappeared from view. And I occasionally saw him when I turned around. But, he did not enjoy it. But me, on the other hand, I was attracted as if it were a game …[i]

“We arrive, it is as though it is some amusement, the people are standing there, we left for school, my poor father stood on the road until I disappeared from view. And I occasionally saw him when I turned around. But, he did not enjoy it. But me, on the other hand, I was attracted as if it were a game …[i]

A final piece of the puzzle

After reading the Congolese comments in La Voix the question naturally arises of whether these points of view corresponded to reality. It has certainly been adequately shown that a rather large gap yawned between the picture the Belgians gave of the situation in the Congo on the one hand and the actual problems of the colonised population on the other. The “elite” of the time were considered in the previous chapter. However, their contributions are situated in a strongly opinion-oriented framework. How education was experienced in practice by the pupils cannot be discovered directly from that. It is a piece that is still missing in the picture I want to reproduce: what was the experience of those who really encountered it? A search into literature on the memories of the education of the colonial period is not very productive. The information is scarce and very scattered. For this reason I considered it useful, in addition to the relatively large amount of written sources available to me, to search for a few people who had been going to school in the period and the region concerned. What they remember, and the way in which they do that, forms a very interesting supplement to the written sources and at the same time clarifies them and also puts them into context. Parts of their testimony have appeared here and there in the previous chapters because they naturally gave information on classroom practices. In this last chapter I want to place the story and the memories of my main witnesses at the centre. What is left from these experiences, what remained and what is their attitude towards this period?

Within (and perhaps because of) the limitations and uniqueness that accompanies this source of information, it is indisputably very interesting to use it in the context of this study. The image of school practices and realities can certainly be supplemented and shown more sharply by listening to the people who experienced it all as pupils. Concerning oral history and the problems of memories in general there is a great deal of scientific literature and in the context of colonial historiography and anthropology (oral) testimony, interview or conversations are sources of information that are being used more and more frequently. My intention here is not to subject the precise nature of all sources to a thorough analysis but I do want to mention a couple of sensible ideas, in my opinion, on the way in which this sort of information can best be dealt with.

Working with memories

Bogumil Jewsiewicki puts what he calls récits de vie at the centre of his social and cultural historical research.[ii] He has even published a number of these life stories and on this occasion formulated some considerations about the nature of these stories. He states that this really relates to a mixed form, something in between social history and telling a story. He emphasised the shifting meaning of stories, which change their context continually between ‘I’ and ‘we’. Your own story simultaneously carries that of the family, the village, the people who share the experience with you. Strongly connected with this is the practice of speaking figuratively; this forms a sort of second layer beneath the facts and events used by the people telling the story or those interviewed. The images used really constitute the assignment of meaning given to the facts and events. On a more direct level Jewsiewicki noticed that in the stories of the Congolese a distinction is often made between ‘us’ and ‘them’. The ‘them’ was primarily the European, the coloniser.

A more personalised implementation of Jewsiewicki’s insights into the ‘I’ and the ‘we’ may be found in the study by Marie-Bénédicte Dembour, Recalling the Belgian Congo.[iii] Dembour pays a great deal of attention to the process of remembering, which seemed to form a central component of her research into the colonial past. From the start of her research she was confronted by the transforming effect of memories and the fact that people integrate their past into their lives and also adapt it. During her interviews Dembour discovered that the interlocutors often gave generally applicable answers and had difficulty in making a distinction between what they formerly thought and what they now thought: “Experiences do not get pigeonholed in one’s memory in a chronological order; rather they are amalgamated in what already exists, slightly changing the tone, adding a dimension, or completely ‘distorting’ the images of the past one keeps.” In the same sense Dembour described a whole series of ways in which memory works: forgetting distasteful things, the incorporation of new facts, striving for coherence and synthesis. Memory continues to modify occurrences with a particular connotation until they get another connotation. Read more

When Congo Wants To Go To School – As Justification And Conclusion

“It puzzled me that colonialism belonged to our recent past. Its legacy was bound to mark our present. I was eager to join in the current research on colonialism that was developing in anthropology. Having completed the study, I remain convinced the Congo was worthy of scholarly attention, although perhaps for different reasons. What strikes me now is that my research illuminates general human processes. I would say that its major significance lies less with either an understanding of the thoughts of Belgian former colonial officers (however these may be needed) or an implicit critique of the literature of the colonial discourse than with an acute perception of the difficulty of attaining knowledge in anthropology. In turn this should make us, as human beings, morally humble and wary of any claim whose legitimacy derives from an easy brand of political correctness. Such a conclusion is not specific of colonialism; it applies to all walks of life.”[i]

“It puzzled me that colonialism belonged to our recent past. Its legacy was bound to mark our present. I was eager to join in the current research on colonialism that was developing in anthropology. Having completed the study, I remain convinced the Congo was worthy of scholarly attention, although perhaps for different reasons. What strikes me now is that my research illuminates general human processes. I would say that its major significance lies less with either an understanding of the thoughts of Belgian former colonial officers (however these may be needed) or an implicit critique of the literature of the colonial discourse than with an acute perception of the difficulty of attaining knowledge in anthropology. In turn this should make us, as human beings, morally humble and wary of any claim whose legitimacy derives from an easy brand of political correctness. Such a conclusion is not specific of colonialism; it applies to all walks of life.”[i]

I have already tried to summarise the main points arising from the “descriptive” chapters in parts II and III in the considerations concluding these chapters. There is consequently little cause to do so again. Rather than repeating these conclusions in this section I would like to consider a number of elements that struck me while studying those realities and practices, and which seem important to me for a proper understanding of the past. It should allow me to formulate a number of considerations or questions concerning the meaning of that image and that past: what does it mean and how should we deal with it?

Colonial education: made in Belgium.

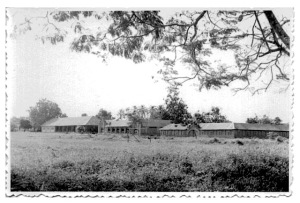

The image of the interaction between the missionaries and the pupils, the method of teaching used or which should have been used in the classroom, the material used – all this points in the same direction: the North. In the Belgian Congo a system was established that was not only loosely based on that implemented in the homeland but that was a very similar copy of it. It is true that a number of differences arose in the quantity of material taught and that a selection of that material was being made, ‘adapted’ to the local circumstances. That does not detract from the essential conclusion that in this case a western educational system was transplanted to the colony. With all its components: the framework, the buildings, the setting, the administrative body, the daily timetable, the teaching method and naturally also the discipline. The first reaction to this was undoubtedly: “But could it have been any different?” The fact that we find it hard to imagine anything else perhaps precisely indicates the importance of this conclusion. In any event it puts matters in the right perspective. In keeping with the quotation by Fabian which I cited in the introduction: we are used to looking back at colonial history and consequently also at the history of Belgian colonisation of the Congo from the perspective of the results achieved. As a result we often forget that it did not have to be like that. Our frameworks of reference restrict us and that is not any different with regard to colonial education.

Two major conclusions follow from this with regard to this study. Firstly, the discussion of the difference between adaptionism and assimilationism must first be brought back to its true proportions: discussions about differences in styles, about the way matters had to be approached. Both movements operated within a framework that remained western in essence. The question of whether indigenism, as a local variant of adaptionism, was also truly more progressive than assimilationism must be answered rather negatively. In the beliefs of the people who gave indigenism its name and who applied it themselves (Hulstaert, Boelaert and other MSC members) it may have been “progressive”. They wanted to defend the Congolese. That belief by Hulstaert and his followers may seem logical, insofar as they compared themselves to other people or groups of colonisers who were much less interested in the welfare of the Congolese. At the same time that is precisely where the shoe doesn’t fit. Hulstaert and his followers seem to act from a genuine conviction, often a type of moral indignation. However, in many cases that moral indignation of the MSC was aimed against modernity. They were truly concerned with the welfare of the Congolese but that primarily meant that they wanted to protect them from themselves and the modern world. However, the fact that at some times their assumptions contrasted sharply with those of the authorities or other players within colonial society gave the MSC an “alternative” aura. It is perhaps better not to say “progressive” because if we associate that with “emancipatory” we must conclude that the actions of the MSC show clear indications of the opposite. The way in which they handled the pupils in practice rather gives an image of a very paternalistic attitude.

A second conclusion is that there was a very great gap between the general, theoretical and fundamental beliefs on the one hand and the practice in the field on the other. At first sight this conclusion seems to fit well with the principle of the grammar of schooling, as formulated and explained by Depaepe and others. Expressed concisely, that principle claims that classroom practice is resistant to innovation to a relatively far-reaching extent. It claims that practice comprises a set of rules, habits, traditions, in which changes are imposed from above but are very hard to implement. The school practices in the Belgian Congo illustrate this very well but not necessarily because so many attempts at innovation were undertaken. This distance between theory and practice may be explained in more detail as a combination of a number of factors. Firstly, the existing (western) grammar had taken root to such an extent with the missionaries that it could literally be imported into an entirely different environment. The consequence thereof was that the missionaries automatically applied personal experiences in the new colonial context. That naturally also had a lot to do with the fact that the majority of missionaries also had a very limited, in some cases non-existent, theoretical background with regard to educational theory. The basis of colonial education was low on theory. Gustaaf Hulstaert is a telling example of this in the given context, precisely because he felt a need to improve his theoretical knowledge or at least to brush it up in the framework of the discussions (and the power struggle) he entered into with the Brothers of the Christian Schools. Read more