John G. Schermer ~ Bonaire families

Bonaireaanse families van 1700 tot 1900

Bonaireaanse families van 1700 tot 1900

Met de eerste versie van deze website wil ik met de Bonaireaanse gemeenschap het resultaat delen van een genealogisch onderzoek gedurende de jaren 1993 tot 2006. Hierna kunnen vernieuwde versies volgen, waarin interpretaties van anderen zijn opgenomen. Het is mijn wens dat deze site als een platform van ideeën over de Bonaireaan en zijn geschiedenis gebruikt zal worden en dat iedere volgende versie bijdraagt aan een meer objectieve benadering van de geschiedenis van Bonaire.

Deze publikatie bestaat uit 2 delen:

– De namen van alle bewoners tussen 1700 en 1900

– Ontwikkeling van Bonaireaanse families

Bij dit onderzoek is uitsluitend gebruik gemaakt van authentieke documenten van het Centraal Historisch Archief te Curaçao, het Nationaal Archief te Den Haag (voorheen Algemeen Rijksarchief) en het archief van de Burgerlijke Stand van Bonaire.

De gegevens over de slaven van de Westindische Compagnie (WIC) komen uit de inventarislijsten van de WIC in het Nationaal Archief te Den Haag.

Gegevens over vrije personen en over slaven die hun vrijheid verkregen zijn gehaald uit de registers van Geboorten, Huwelijken en Overlijden te Bonaire tussen 1830 en 1900.

Gegevens over gouvernementsslaven (katibu di Rei) en partikuliere slaven (katibu di Shon) zijn verkregen uit de correspondentie met het Ministerie van Kolonieën, bewaard in het Centraal Historisch Archief te Curaçao.

Er is geen gebruik gemaakt van bestaande studies, interpretaties en publikaties van Dr. J. Hartog, R.H. Nooijen o.p. en de vele publikaties van Bòi Antoin.

In de bijlagen is een lijst van aanbevolen literatuur opgenomen.

Namen van alle bewoners tussen 1700 en 1900

Dit deel toont de genealogie van het Bonaireaanse volk onderverdeeld in vier categorieën van families.

A. Slaven van de Westindische Compagnie (WIC) – 1700-1791

B. Gouvernementsslaven – 1800-1863

C. Partikuliere slaven – 1800-1863

D. Vrije personen – 1800-1900

A. De slaven van de WIC zijn nog onder te verdelen in vier groepen:

1. Slaven die gezinnen vormen en zo als de basis van de Bonaireaanse gemeenschap gelden.

2. Slaven die in deze periode gekocht zijn.

3. Slaven met een van oorsprong Afrikaanse naam.

4. Slaven met een kreoolse naam.

B. In 1791 toen de WIC ophield te bestaan zijn alle slaven overgenomen door het gouvernement en daarom vinden wij deze slaven tot 1863 voortaan op de inventarislijsten van het gouvernement.

C. De derde categorie zijn de particuliere slaven. In 1863 ontvingen alle slaveneigenaren van het gouvernement de som van 400 florin per slaaf. De borderellen (zie lijst 7) hielpen ons aan gegevens over deze groep slaven.

D. De laatste categorie zijn de vrije personen die na 1791 toestemming van de overheid hadden gekregen om zich op Bonaire te vestigen. Read more

Eleonore Merza ~ The Israeli Circassians: Non-Arab Arabs

Bulletin du Centre de recherche français à Jérusalem (2012) One day, I was at the tahana merkazit [central bus station] in Jerusalem with Mussa and we went through the metal detector. They let him go through but when it was my turn, they asked for my identity card. They saw that we kept talking together so they asked for his I.D. too. He is a redhead and has blue eyes so they thought he was Ashkenazi. But they saw his name ‘Musa’ – that sounds quite Arabic and they asked him if he was Arab, but then his family name doesn’t sound Arabic at all so he explained that he was Circassian. Then, they asked him what religion he was and he said ‘Muslim’. They were dumbfounded…

Bulletin du Centre de recherche français à Jérusalem (2012) One day, I was at the tahana merkazit [central bus station] in Jerusalem with Mussa and we went through the metal detector. They let him go through but when it was my turn, they asked for my identity card. They saw that we kept talking together so they asked for his I.D. too. He is a redhead and has blue eyes so they thought he was Ashkenazi. But they saw his name ‘Musa’ – that sounds quite Arabic and they asked him if he was Arab, but then his family name doesn’t sound Arabic at all so he explained that he was Circassian. Then, they asked him what religion he was and he said ‘Muslim’. They were dumbfounded…

The 4,500-odd Israeli Circassians, who arrived during the second half of the 20th century in what was then part of the Ottoman Empire, have an unusual identity: they are Israelis without being Jews and they are Muslims but aren’t Palestinian Arabs (they are Caucasians). Little known by the Israeli public, the members of this inconspicuous minority often experience situations like the one reported above; indeed, many of them have a fair complexion and light-colored eyes that don’t match the widely spread (and expected) clichés about Muslims’ physical traits. At the same time, many Circassians – men, in particular – bear a Muslim name, which immediately causes them to be classified as “Arabs.”

Until 1948, the Zionist project’s exclusive aim was the establishment of a Jewish state – not the establishment of a state where Jews could finally live far from the anti-Semitic threat. In The Jewish State, Theodor Herzl had already stated that “the nations in whose midst Jews live are all either covertly or openly Anti-Semitic”2 and the establishment of a Jewish state was the future as Zionism saw it. In fact, when the State of Israel was declared, it was defined as the state of the Jewish people, inheritor of the Biblical land of Israel and of the kingdom of Judah. This exclusive definition has made the creation of citizenship categories quite arduous. Actually, some figures of Zionism opposed Herzl’s political Zionism even before the creation of the state. One of them was Asher Hirsch Ginsberg, better known under his pen name Ahad Ha’am. Even though Ahadd Ha’am received the Zionist circles’ moral support, he was convinced that the future state could not ingather all the Jews and he fought Herzl’s political Zionism. After his visits in Palestine, the author wrote down his impressions and criticized the functioning of settlements. In his essay Emet me-Eretz Yisrael [A Truth from Eretz Yisrael], he denounced the myth of the virgin land conveyed by the Zionist leaders and reminded them that their analysis did not take into account the Arabs:

From abroad, we are accustomed to believe that Eretz Israel is presently almost totally desolate, an uncultivated desert, and that anyone wishing to buy a land there can come and buy all he wants. But in truth it is not so. In the entire land, it is hard to find tillable land that is not already tilled […] We are accustomed to believing that Arabs are all desert savages, like donkeys who do not see or understand what is going on around them. This is a serious mistake.

The complete essay: https://journals.openedition.org/bcrfj/7250

Référence électronique

Eleonor Merza,The Israeli Circassians: non-Arab Arabs, Bulletin du Centre de recherche français à Jérusalem [En ligne], 23 | 2012, mis en ligne le 20 février 2013, Consulté le 10 juin 2020.

Eleonore Merza is a political anthropologist; she completed her doctorate at the EHESS. She is an associate researcher in the Anthropology of Organizations and Social Institutions Research Unit at the Interdisciplinary Institute for the Anthropology of Contemporary Societies (IIAC-LAIOS: CNRS-EHESS). She currently pursues post-doctoral studies at the French Research Center in Jerusalem (CRFJ). Her doctoral thesis focused on the identity of the Circassian minority in Israel and her current research deals with non-Jewish citizens, minorities, and co-existence in today’s Israeli society. She taught at the School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences (EHESS) where she was a lecturer on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Träume ich von Israel

Träume ich von Israel

frag ich mich, was kann noch werden

ich will bessere Nachrichten in der Zeitung lesen

mein Arabisch aufbessern, mit ihm Frieden schließen

ich will in Gaza meine Gedichte lesen, dann in den Nahostzug steigen

in Haifa halten (‘n paar Kleider und Bücher nehm ich mit)

und zur Überraschungsparty meiner Großmutter fahren

in Bagdad

Denk ich an Israel,

an ihren Beitritt in die Nahostunion,

die, wie die europäische –

Israel, was lachst Du mich aus,

Wirklichkeit zeugt doch für das unsichtbare Ringen der Träume

Ich will dahingleiten, frei in der Luft, die sich zwischen Haifa und Beirut erstreckt

will, wie die Wandervögel, ganz Europa durchwandern, Asien und Afrika,

ohne Paß, ohne Nationalität wissen sie mehr über uns,

als wir je wissen werden

unsere Konflikte und Probleme kennen sie

und kommen doch jedes Jahr aufs Neue zurück

(muß leider gerade lesen sie werden weniger)

Träume über Israel, ganz gewöhnliche,

ich phantasiere über Möglichkeiten,

Dich neu zu dichten.

–

Mati Shemoelof – Bagdad, Haifa, Berlin. Gedichte. AphorismA Verlag, Berlin, 2019. ISBN 978 3 96575 076 1

Mati Shemoelof & Joseph Sassoon Semah ~ How to Explain Hare Hunting To A Dead German Artist

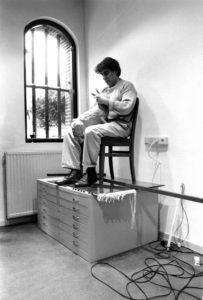

Joseph Sassoon Semah, How to Explain Hare Hunting to a Dead German Artist, February 24, 1986. Photography: Olaf Bergmann. Courtesy of Joseph Sassoon Semah

Tohu Magazine, February 6, 2019. Joseph Sassoon Semah, a Baghdad-born artist who now lives and works in Amsterdam, is about to embark on an extensive multi-site project, in Amsterdam, Jerusalem, and Baghdad. Berlin-based poet and author Mati Shemoelof talks with him about his years living as an artist in Israel versus being a Babylonian Jew and an artist in Europe. They discuss Judaism, diaspora, exclusion, and acts of concealment and building.

The artist Joseph Sassoon Semah has never before given an interview to an art publication in Israel. The Israeli art world has not adequately recognized his work. Although he showed in several important institutions in Israel and worked with key curators, it was negligible compared with the scope of his oeuvre, especially following his move from Israel to Europe. What would have happened had he stayed in Israel? Was he stumped by his diasporic state or was he ahead of his time in dealing with the Jewish component of his art? It is not merely an objective issue to be measured by the number of exhibitions, but rather the artist’s subjective sense of his position in the art field. I gather from Semah that he has remained on the outside, beyond the walls of Jerusalem. In Europe, too, and especially in the Netherlands, his work is not widely known yet. This interview stems from my own interest in Semah’s identity (we are both of a Jewish Iraqi descent) and his work, but also as an intra-European process of an artistic, inter-generational analysis attempting to formulate the role of Jewish culture in Europe.

Semah was born in Baghdad, Iraq, in 1948. His grandfather, Hacham Sassoon Kadoorie, was the chief rabbi of Baghdad’s Jewish community until his passing in 1971, even after they had all emigrated. In 1950, Semah and his family were uprooted from Iraq, and they moved to Israel. He grew up in Tel Aviv. Traumatized by his military service in the 1967 and 1973 wars, he chose exile and has been living in the Netherlands since 1981. The grandfather’s continued residence in Baghdad, along with some 20,000 more Jews, brings to mind Semah’s own position in Amsterdam (his grandfather did not immigrate to Israel, and Semah emigrated from Israel – both had chosen a diasporic existence as a Jewish minority under a Muslim/Christian majority), where he now lives with his partner, Linda Bouws. She runs the institute they co-founded, Metropool – Studio Meritis MaKOM: International Art Projects. My grandmother, Rachel Kazaz, had also been among the displaced Baghdadi Jews. My acquaintance with the pain and the uprooting enabled me to write about the mysterious affair that drove the Jews of Iraq to abandon their property, their culture, and their way of life within just a year; the affair that involved bombing Jewish centers in Baghdad, including the synagogue of Semah’s grandfather.[1]

Stijlcitaat of plagiaat? Een vergelijking tussen Godfried Bomans en andere auteurs in 2 delen

I.

Is men het, dan is men het ook – Onmiskenbare overeenkomsten tussen het werk van Dickens en van Bomans en ’t Hart

Wanneer is er nog sprake van inspiratie en wanneer van leentjebuur? Wanneer is iets een literair stijlcitaat en wanneer ouderwets jatwerk? De grens tussen je laten souffleren of je laten inspireren is zelden scherp.

Om een verhaal of roman te schrijven put een auteur behalve uit zijn fantasie ook uit zijn eigen ervaringen. Daaronder vallen ook zijn leeservaringen. Elke schrijver is beïnvloed door de werken die hij gelezen (en vooral herlezen) heeft. Die invloed blijkt doorgaans uit verwantschap in thematiek, symboliek en stijl. Veel lastiger is het passages te vinden waarin concrete overeenkomsten zijn aan te wijzen tussen het oorspronkelijke werk en dat van een schrijver die met dat werk bekend is. En nog lastiger – maar wel intrigerender – is de vraag die in het verlengde daarvan ligt: wanneer is er nog sprake van beïnvloeding en wanneer van kopieerlust of plagiaat?

Als we plagiaat niet beperkt definiëren – d.w.z. als het woordelijk overnemen van (fragmenten uit) werk van anderen, maar daaronder ook laten vallen het aantoonbaar van beelden gebruik maken en uit de sfeer lenen van andere auteurs, blijkt dat de grens tussen wat nog wel geplagieerd is en wat (nog net) niet, niet alleen vaag is ook maar subjectief.

Dat bleek mij toen ik twee fragmenten van Dickens vergeleek met de corresponderende fragmenten uit werk van twee Nederlandse auteurs, Maarten ‘t Hart en Godfried Bomans, beide erkende Dickens-kenners.

Bij ‘t Hart viel me een passage op die me sterk deed enken aan een scene in het tweede hoofdstuk van Great Expectations (1861):

My sister had a trenchant way of cutting our bread-and-butter for us, that never varied. First, with her left hand, she jammed the loaf hard and fast against her bib – where it sometimes got a pin into it, and sometimes a needle, which we afterwards got into our mouths. Then she took some butter (not too much) on a knife and spread it on the loaf, in an apothecary kind of way, as if she were making a plaister – using both sides of the knife with a slapping dexterity, and trimming and moulding the butter off round the crust. Then, she gave the knife a final smart wipe on the edge of the plaister, and then she sawed a very thick round off the loaf: which she finally, before separating from the loaf, hewed into two halves, of which Joe got one, and I the other.

Deze opmerkelijke manier om een boterham te smeren en af te snijden – in die volgorde – keert terug in Maarten ‘t Harts roman De droomkoningin (1980):

Zo zat ik even later met tante Riekie in de kleine huiskamer achter de winkel. Al dadelijk zag ik dat ze alles veel te woest deed. Bovendien smeerde ze het brood op een wonderlijke manier. Met het broodmes deed ze een woedende uitval naar de botervloot, zwaaide dan de van een grote geleklodder voorziene punt naar het brood toe en smeerde het brood op het snijvlak. Daarna pas sneed ze de boterham af.

Vol verbazing staarde ik naar deze ongebruikelijke gang van zaken. Toen ze opnieuw wilde beginnen,

merkte ik op: ’Je moet eerst de boterham eraf snijden.’

’Wel allemachtig, klein kreng, wat zal ik nou beleven? Zal ik niet weten hoe je brood moet klaarmaken? Ik heb al in duizenden gezinnen gebakerd, ik ben hier ook al geweest.’

’Wanneer?’ vroeg ik verbaasd.

’Toen jij geboren werd.’

‘Toen ik geboren werd?’

‘Ja.’

‘Heb je de engel gezien die mij gebracht heeft?’

’Engel? Engel? Allemachtig, moet je zo’n kleine snotneus horen! Hier, je boterham. Wat wil je erop?’

’Kaas.’

‘Kaas? Op je eerste boterham al kaas? Wat een verwennerij! Daar doe ik niet aan mee, jij eet maar netjes basterdsuiker op je eerste boterham. Het geld groeit hier niet op jouw vaders rug.’

‘Van mijn moeder mag ik wel kaas op m’n eerste boterham.’

‘Niks mee te maken, verwend kreng. Eerst bruine suiker.’

Met twee armen en handen tegelijk was ze in de weer om mijn boterham van bastaardsuiker te voorzien. Ze stampte zelfs met haar voet. De suikerpot vloog door de lucht alsof hij gevleugeld was; haar armen in de zwarte mouwen fladderden als roeken over de tafel en de kromme, gesnavelde vingers stortten de suiker op en vooral naast de boterham zodat het leek of alles werd omgekeerd: daar lag het sneeuwwitte tafellaken en nu daalde er bruine aarde op neer. Met het broodmes plette ze de suiker op de boterham tot een gladde bruine ijsbaan. Toen zette ze hem voor mij neer. Ik keek naar al die platgeslagen suiker en zei laconiek, terwijl ik het bord waarop het brood lag, wegduwde: ‘Dan hoef ik niet.’

Tamar Morad, Dennis Shasha & Robert Shasha ~ Iraq’s Last Jews: Stories Of Daily Life, Upheaval, And Escape From Modern Babylon

Palgrave Studies In Oral History- 2008 – Series Editors’ Foreword

Palgrave Studies In Oral History- 2008 – Series Editors’ Foreword

In another book in the Palgrave Studies in Oral History series, Soldiers and Citizens, an Assyrian Christian explains how his group in the Iraqi town of Dora was threatened with death if they didn’t convert to Islam or pay a special tax or abandon their homes and leave within 24 hours. He remarked, “I heard there was talk of doing to the Christians what they did to the Jewish in the 1940s.”1 The year 1941 witnessed the Farhoud, a Nazi-inspired pogrom, which began a series of events that propelled a Jewish exodus from Iraq. Of the approximately 137,000 who resided in Iraq during the early 1940s, 124,000 had fled, most to Israel, by 1952. The relatively few left behind suffered as a result of the Six Day War in 1967 when Iraq restricted their movement, jobs, and opportunity to communicate in and outside of the country. Some suffered imprisonment and torture. Hence, the once vital and vibrant Iraqi Jewish community had all but disappeared from its homeland by the 1970s. Oral histories have widely documented the Holocaust, but the stories recounted in this volume are less well-known and serve to expand our knowledge of Middle Eastern Jews outside of Israel. Oral history is particularly well suited to capture the drama and trials of this historical experience and to humanize the past condition of a community that exists in exile. With American attention focused upon Iraq as a consequence of two recent wars, public curiosity about that nation will benefit from these accounts. Iraq’s Last Jews joins a number of other volumes in this series that consider issues of world-historical significance. Whether it be the contemporary Iraq War or the decades-past Chinese Cultural Revolution, or any number of other topics, the series encourages the employment of oral history to investigate the memories of ordinary and extraordinary people in order to make sense of past and present.

Bruce M. Stave University of Connecticut – Linda Shopes Carlisle, Pennsylvania

Preface

Some 2,500 years after the first Jews established roots in Babylon, the once-vibrant and prosperous Jewish community of Iraq has disappeared. A community that numbered close to 140,000 in the late 1940s—and comprised fully one-third of Baghdad’s population—consisted of a mere 20 when U.S. tanks rolled into the Iraqi capital in 2003. Today, fewer than ten Jews remain in Iraq. Yet as late as the 1920s and 1930s, Iraqi Jews felt the heady potential of full equality in a secular society for the first time in their long history of subordination to Muslim rulers. From music to politics to commerce, Jews played a major role in Iraqi society and culture. For centuries after the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem, Babylon was the world’s epicenter of Jewish life and religion—the place where the Babylonian Talmud was written and where rabbis from across the region and Europe came to learn from the most scholarly sages. But the community dissolved in the middle of the 20th century when pro-Nazi forces, Arab nationalism, and the formation of Israel led to violence against and a general sense of insecurity among Iraqi Jews, causing them to flee, mostly over the course of about a year and a half. This book tells the story of that last generation, people who in many cases grew up with strong patriotic feelings but were always prepared for a future beyond Iraq’s borders—just in case. The storytellers of these first-person accounts vary as widely as any group of Jews does, reflecting the breadth and texture of the community: wealthy businessmen and Communists, popular musicians and reformist writers, Iraqi patriots and early Zionists. Many had close friends among the Muslims and Christians of Iraq of whom they speak warmly. They tell the tales of a people with a love for their birth country that persisted even as they were forced to leave their homes. The story of the final decades of the Jewish community in Iraq divides into three periods. First is the period before 1939 when the Jews in Iraq saw themselves as part of the Iraqi national fiber in government, commerce, and the arts. That ended verbally with the rise of Nazi influences and violently with the Farhoud, a pogrom against the Jews, in 1941. Second is the period between then and 1953 when Arab hostility toward the new state of Israel turned most Jews into Zionists and the vast majority of the community left. The final period records an Iraq that drifted towards increasingly autocratic leadership, culminating in the sadistic dictatorship of Saddam Hussein, with the Jews often playing the role of scapegoat. Finally, the book closes with several moving retrospectives of the community. These stories are sometimes funny, often tragic, touching, and insightful. Readers will find that the editors, in addition to recording descriptions of daily life, have also uncovered acts of heroism, adventure, and intrigue: from the undercover Israeli agents who helped orchestrate the mass emigration of Iraqi Jews to the young Jewish state at mid-century, to those who argued for the lives of their loved ones in the brutal prisons of Saddam Hussein. What has been compiled here, ultimately, is a book about quiet bravery in times of distress and a celebration of the possibility of peace.

Copyright © Tamar Morad, Dennis Shasha, and Robert Shasha, 2008. All rights reserved. First published in 2008 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN® in the United States—a division of St. Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

The complete book: https://epdf.pub/iraqs-last-jews-stories-of-daily-life-upheaval-and-escape-from-modern-babylon-pa.html