Chomsky: Biden’s “Radical” Proposals Are Minimum Measures To Avoid Catastrophe

Looking at the state of the world, one is struck by the stark contradiction of progress being made on some fronts even as we are facing massive disruptions, tremendous inequalities and existential threats to humanity and nature.

In this context, how do we evaluate the qualities of progress and decline? How significant is political activism to progress?

In this exclusive interview, Noam Chomsky, one of the world’s greatest scholars and leading activists, shares his insights on the state of the world and the conundrum of activism and change, including the significance of the Black Lives Matter movement, the movement for Palestinian rights, the urgency of the climate crisis and the threat of nuclear weapons.

C.J. Polychroniou: It’s been said by far too many, including myself, that we live in dark times. And for good reasons. We live in an era where the rich get richer and the poor get poorer, authoritarianism is a global political phenomenon, and life on Earth is entering a state of collapse. From that perspective, human civilization is on an inexorable course of decline and nothing but a radical overhaul of the way humans conduct themselves will save us from a return to barbarism. Yet, there are at the same time signs of progress on numerous fronts, which are hard to overlook. Societies are becoming increasingly multicultural and also more aware of and sensitive to patterns of racism and discrimination. In the light of all this, do we see the glass half empty or half full? Moreover, is it possible to evaluate the qualities of decline and progress scientifically, or do we have to rely purely on normative evaluations and value judgments?

Noam Chomsky: There are attempts to measure the contents of the glass. The best-known is the Doomsday Clock of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, with the hands placed a certain distance from midnight: the end. Each year that Trump was in office, the minute hand was moved closer to midnight, soon reaching the closest it had ever been, then going beyond. The analysts finally abandoned minutes and turned to seconds: 100 seconds to midnight, where the Clock now stands. That seems to me a fair assessment.

The analysts identify three major crises: nuclear war, environmental destruction and the deterioration of rational discourse. As we’ve often discussed, Trump has made a signal contribution to each, and the party he now owns is carrying his legacy forward. They are also currently hard at work to regain power by overcoming the dread danger of a government of the people, with plenty of far right big money at hand. If the project succeeds, emptying of the glass will be accelerated.

There has indeed been progress on many fronts. It is startling to look back and see what was regarded as proper behavior and acceptable attitudes not many years ago, even written into law. While substantial, the progress has not, however, been sufficient to contain and reverse the continuing assault on the social order, the natural world and the climate of rational discourse.

Without disparaging the great activist achievements, it’s hard sometimes to suppress memory of an ironic slogan of the ‘60s: They may win the battles, but we have all the best songs.

The glass that is before our eyes is not an encouraging sight, to put it mildly. Take the state of the three major crises identified in the setting of the Clock.

The major nuclear powers are obligated by the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty “to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament, and on a treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control.”

They are pursuing the opposite course.

In its latest annual survey, the prime monitor of global armament, the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, reports that “The growth in total spending in 2020 was largely influenced by expenditure patterns in the United States and China. The USA increased its military spending for the third straight year to reach $778 billion in 2020,” as compared with China’s increase to $252 billion. In fourth place, below India, is the second U.S. adversary, Russia: $61.7 billion.

The figures are instructive, but misleading. The U.S. is alone in facing no credible security threats. The threats that are invoked in the calls for even more military spending are at the borders of adversaries, which are ringed with U.S. nuclear-armed missiles in some of the 800 U.S. military bases around the world (China has one, Djibouti).

Further threats, in this case quite real, are the development of new and more dangerous weapons systems. They could be banned by treaties, which were effective, until they were mostly dismantled by Bush II and Trump.

With Earth On Edge, Climate Crisis Must Be Treated Like Outbreak Of A World War

Humanity and the environment are under massive assault by global warming caused by human activities.

The new Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report released today, August 9, 2021—the first of four that make up the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment report—reiterates in scientific language (it deals with the physical science basis of global warming) what we have already known for quite some time from scores of previous studies: humanity faces a climate emergency, global warming is human driven, major climate changes are irreversible, and time is running out to avoid a catastrophe of unimaginable proportions.

It is, nonetheless, an extremely valuable report because a damning indictment of humanity’s wholly destructive actions towards all life on Earth now carries the stamp of approval by the world’s most authoritative voice on climate science. And, ironically enough, the new IPCC’s 6th Assessment climate report is also approved by the very same entities—195 member governments—largely responsible, although surely not all to the same extent, for the looming global climate catastrophe.

United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres described the report as “a code red for humanity.” U.S. Special Presidential Envoy for Climate, John Kerry said the report made clear the “overwhelming urgency of this moment.” And U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson said the report is “sobering reading” and should serve as a “wake-up call” for global leaders ahead of the COP26 summit, which will be held in Glasgow from 31 October—12 November 2021.

The planet is expected to warm by at least 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2040, according to the IPCC’s latest findings. But the report also underscores the key point that, without “immediate, rapid and large-scale reductions in greenhouse gas emissions,” even limiting warming to even 2 degrees “will be beyond reach.”

The IPCC’s latest report points to temperatures rising faster than previously thought. In fact, on current trends the world is moving fast towards 3 degrees Celsius.

Coincidentally, once the average global temperature rises 1.5 degrees Celsius above the pre-industrial level, the planet will experience a surge in climatic tipping points, resulting in fiercer heatwaves, melting ice, rising sea levels, and severe droughts.

Yet, the scientists behind the writing of the latest IPCC report say that the worse can be avoided if the world acts fast. In other words, rescuing the planet comes down to politics—and economics. And to human nature, one might add.

There is no doubt that the task ahead is exceedingly difficult, to say the least. A global existential crisis must be addressed in a world occupied by primarily egoistic and highly imperfect creatures; where the nation-state remains the primary political unit; and with an economic system in place that is destructive and unsustainable. Nonetheless, the odds can be overcome because it’s either survival or extinction. Reason must prevail, international cooperation needs to replace national antagonisms, and sustainability take priority over short-term profits.

All of the above are realizable goals through a political decision to move away from the fossil fuel economy and, in turn, to implement a green new deal on a global scale.

World War II was won through economic breakthroughs, technological cooperation, and the formation of a primary alliance against the Axis powers.

The climate crisis must be treated like a world war—World War III. Humanity and the environment are under massive assault by global warming caused by human activities. The biggest polluters on the planet—U.S., China, India, Russia, Japan, Germany—must form an alliance to lead the global economy away from fossil fuels as quickly as possible. The rich countries, which are responsible for the climate crisis, also have a responsibility to finance the bulk of the transition to a global green economy. Moreover, various studies have shown that financing the Global Green New Deal is not a particularly challenging task. UMass-Amherst economist Robert Pollin, for example, has argued that there are several large-scale funding sources for the greening of the global economy, and they include things such as carbon tax, the transfer of funds out of military budgets, lending programs introduced by Central Banks, and the elimination of all fossil fuel subsidies. He has also estimated, a figure corroborated by other similar studies, that the cost of the clean energy transformation would require an average spending of about $4.5 trillion per year between 2024 and 2050 (which is when most countries have committed to reaching zero emissions.

In sum, all is not yet lost, which is also the conclusion of the ICPP’s latest report. Of course, whether we can overcome the institutional, structural, and even intrinsic obstacles to designing a long-term, truly sustainable world economy remains to be seen. But if we convince ourselves that combatting the climate crisis is equivalent to fighting a world war, we do have a realistic chance of rescuing planet Earth.

Source: https://www.commondreams.org/earth-edge-climate-crisis-must-be-treated-outbreak-world-war

Our work is licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0). Feel free to republish and share widely.

C.J. Polychroniou is a political economist/political scientist who has taught and worked in numerous universities and research centers in Europe and the United States. His latest books are Optimism Over Despair: Noam Chomsky On Capitalism, Empire, and Social Change” and “Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet” (with Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin as primary authors).

Wat is lang? Een onderzoek naar lange filmtitels

Ach, wat is lang? Dat is relatief.

Ach, wat is lang? Dat is relatief.

Night of the day of the dawn of the son of the bride of the return of the revenge of the terror of the attack of the evil, mutant, crawling, alien, flesh-eating, hellbound, subhumanoid , zombiefied living dead part 2: in shocking 2-D (2011), bijvoorbeeld, wordt met zijn 40 woorden in vakkringen beschouwd als langste filmtitel.

Het is een parodie op The night of the living dead (1968), de titel van de film waarmee George A. Romero zijn regiedebuut maakte met een budget van slechts $ 150.000,-, een film die nog altijd een van de best gewaardeerde griezelfilms is.

De grap is dat in die ellenlange titel de namen van tal van andere films zijn verwerkt. Om te beginnen die van Romero, maar voorts ook bijvoorbeeld The revenge of the dead (1960), The bride of the monster (1955) of The attack of the killer-tomatoes (1980). Om een idee te geven. En er wordt ook nog een lijst met cliché-monsters bij geleverd, van mutant tot flesh-eating aan toe.

Als uitgangspunt voor hun selectie beperkten de vakkringen zich tot speelfilms – dus geen documentair of educatief werk – van Engelstalige – lees: Amerikaanse – makelij. Niet dat in het Frans – Chacun son cinéma ou Ce petit coup au coeur quand la lumière s’éteint et que le film commence (2007, 18 woorden) -, Duits – Die Antigone des Sophokles nach der Hölderlinschen Übertragung für die Bühne bearbeitet von Brecht 1948 (Suhrkamp Verlag) (1992, 17 woorden) -, Spaans – Mil nubes de paz cercan el cielo, amor, jamás acabarás de ser amor (2003, 13 wooorden) – of Italiaans – Film d’amore e d’anarchia, ovvero ‘stamattina alle 10 in via dei Fiori nella nota casa di tolleranza… (1973, 17 woorden) – geen lange titels bestaan, maar Amerika ziet zichzelf graag als het centrum van de cinematografische industrie en dat is, eerlijk gezegd, niet eens helemaal ten onrechte.

Pseudo-humor

Mocht u niettemin de indruk hebben dat overdreven lange titels zich bij uitstek lenen voor slechte horror – Oh Snap! I’m trapped in the house with a crazy lunatic serial killer! (2008, 13 woorden) – of voor de pseudo-humor van films op het bedenkelijke niveau van I could never have sex with any man who has so little regard for my husband (1973, 16 woorden), dan wordt het tegendeel bewezen door de verfilming van The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum at Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade (1967, 25 woorden). Die is gebaseerd op Marat/Sade, het van oorsprong Duitse toneelstuk van Peter Weiss, zoals gespeeld door de Royal Shakespeare Company. Het geheel draait om een toneelstuk – de moord op de Franse filosoof Marat – in de versie van de bewoners van het krankzinnigeninstituut Asile de Charenton in Noord-Frankrijk onder de regie van Marquis de Sade, die daar zelf lang heeft verbleven en er ook zou sterven.

Kort

Kort

De vraag naar de langste titel brengt automatisch ook de zoektocht naar de kortste mee. Om die eer strijden drie films, een Amerikaanse en twee Europese. Q (1982) heette oorspronkelijk The winged serpent, De gevleugelde slang, en dat zou al genoeg moeten zeggen. Een prehistorisch Azteeks afgodsbeeld komt tot leven in zijn nest bovenop een New Yorkse wolkenkrabber en zaait dood en verderf onder de betere kringen in Manhattan.

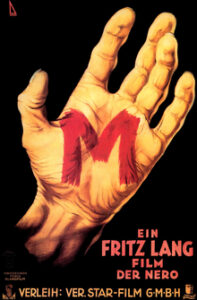

M (1931) van regisseur Fritz Lang is, in contrastrijk zwart-wit gefilmd, een klassiek voorbeeld van Duits expressionisme. Maar M (de afkorting voor Mörder) is vooral nog steeds de moeite waard om de angstaanjagende rol van Peter Lorre als kindermoordenaar.

Er werd in 1951 door Joseph Losey een remake van gemaakt, maar dat bleek een slap aftreksel. Het was ook de inspiratie voor Shadows and fog (1992), een van de betere Woody Allen films.

De tweede niet-Amerikaanse productie is Z (1969), het portret van Griekenland onder het kolonelsregime waarvoor regisseur Constantin Costa-Gavras de Oscar voor beste buitenlandse film werd toegekend. De film heette aanvankelijk The anatomy of a political murder, Z – Grieks voor “Hij leeft” – is het protestsymbool voor het slachtoffer van die moord.

Wim en Pim

Wim en Pim

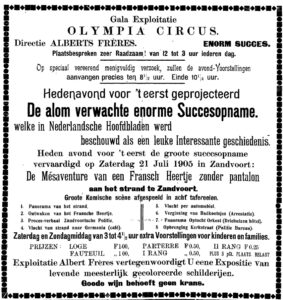

Wie onder Nederlandse films naar lange titels wil zoeken, heeft een indrukwekkende geschiedenis tot zijn beschikking. Opmerkelijke voorbeelden van ver vóór het digitale tijdperk zijn De mesaventure van een Fransch heertje zonder pantalon aan het strand te Zandvoort (1905, 13 woorden) en Het gestolen kind, door de trouwe Nero teruggevonden (1905, 8 woorden).

Maar echt op zoek naar lange Nederlandse filmtitels komt men al snel terecht bij het subsidieverslindende duo Wim Verstappen en Pim de la Parra, in de filmwereld bekend als “Wim en Pim”. Zij schonken ons films met namen als De minder gelukkige terugkeer van Joszef Katús naar het land van Rembrandt (1966, 12 woorden).

De intrigerendste is Mijn nachten met Susan, Olga, Julie, Piet en Sandra (1975, 9 woorden), die in de voorpubliciteit werd gepresenteerd als een “sex-psycho, suspense mystery thriller”, maar die in de praktijk, dat wil zeggen in de woorden van Ab van Ieperen in het NRC, werd getypeerd als “het werk van een niet onbegaafde filmamateur die op een landerige namiddag een ideetje heeft gekregen en dat onmiddellijk ten uitvoer heeft gebracht, zonder zich af te vragen of het eigenlijk wel zo’n goed idee was.”

Dat Pim de la Parra het ook alleen af kon, bewees hij met Paul Chevrolet en de Ultieme Hallucinatie (1985, 6 woorden). In Hollands Hollywood, dat een overzicht biedt van “Alle Nederlandse speelfilms van de afgelopen zestig jaar” (Amsterdam, 1995), doet Henk van Gelder een poging de chaos te schetsen te midden waarvan de film moest ontstaan.

Het is “het verhaaltje van een succesvolle, maar gescheiden thrillerschrijver, die doende is zijn relatie tot vrouwen te onderzoeken – of zoiets, want De la Parra was er de man niet naar om een strakke, glasheldere plot te ontwerpen.

Het is “het verhaaltje van een succesvolle, maar gescheiden thrillerschrijver, die doende is zijn relatie tot vrouwen te onderzoeken – of zoiets, want De la Parra was er de man niet naar om een strakke, glasheldere plot te ontwerpen.

Met de voornaamste acteurs werd een week gerepeteerd, waarbij iedereen naar hartenlust dialogen kon improviseren binnen de opzet. Karin Loomans noteerde die dialogen dan en stelde iets samen dat op een uitgewerkt draaiboek leek. Maar ook tijdens de opnamen was improvisatie nog mogelijk.”

Na de première is nooit meer iets van de film gehoord.

Is A Return To Barbarism Unavoidable?

A cursory glance at the state of today’s world will give pause to anyone wishing to celebrate humanity’s progress. In fact, evidence abounds that the possibility of a reversion to barbarism should not be rejected as too far-fetched.

We live in a period of great global complexity, confusion and uncertainty. We are in the midst of a whirlpool of events and developments that are eroding our capability to manage human affairs in a way that is conducive to the attainment of a political and economic order based on stability, justice and sustainability. Indeed, the contemporary world is fraught with perils and challenges that will test severely humanity’s ability to maintain a steady course towards anything resembling a civilized life.

For starters, we have been witnessing the gradual erosion of socio-economic gains in much of the advanced industrialized world since the late 1970, along with the rollback of the social state, while a tiny percentage of the population is wealthy beyond imagination that compromises democracy, subverts the “common good” and promotes a culture of dog-eat-dog world. The pitfalls of massive economic inequality were identified even by ancient scholars, such as Aristotle, and yet we are still allowing the rich and powerful not only to dictate the nature of society we live in but also to impose conditions that make it seem as if there is no alternative to the dominance of a system in which the interests of the rich have primacy over social needs.

In this context, the political system known as representative democracy has fallen completely into the hands of a moneyed oligarchy which controls humanity’s future. Democracy no longer exists in any meaningful sense. The main function of the citizenry in so-called “democratic” societies is to elect periodically the officials who are going to manage a system designed to serve the interests of a plutocracy and of global capitalism. The “common good” is dead, and in its place we have atomized, segmented societies in which the weak, the poor and powerless are left at the mercy of the gods.

The above features capture rather accurately, in my view, the socio-economic landscape and political culture of “late capitalism.” Nonetheless, the prospects for radical social change do not appear highly promising. Darkening times, strangely enough, have never favored the Left. And today’s Left appears preoccupied with identity politics and culture, while unified ideological gestalts guiding social and political action towards the building of a new socio-economic social order are sorely missing. What we may see then emerge in the years ahead is an even harsher and more authoritarian form of capitalism.

Then, there is the global warming phenomenon, which threatens to lead to the collapse of much of civilized life if it continues unabated. The extent to which the contemporary world is capable of addressing the effects of the climate crisis— heatwaves, frequent wildfires, longer periods of drought, rising sea levels, waves of mass migration — is indeed very much in doubt. Moreover, it is also unclear if a transition to clean energy sources, which is slow to emerge, even suffices at this point in order to contain the further rising of temperatures. To be sure, the global climate crisis will produce in the not-too-distant future major economic disasters, social upheavals and political instability.

If the climate change crisis is not enough to make one convinced that we live in ominously dangerous times, add to the above picture the ever-present threat of nuclear weapons. In fact, the threat of a nuclear war or the possibility of nuclear attacks is probably more pronounced in today’s global environment than any other time since the dawn of the atomic age. A multi-polar world with nuclear weapons is a far more unstable environment than a bipolar world with nuclear weapons, particularly if we take into account the growing presence and influence of non-state actors, such as extreme terrorist organizations, and the spread of irrational and/or fundamentalist thinking, which has emerged as the new plague in many countries around the world, including first and foremost the United States.

The above reflections are not intended to cause despair, or even to suggest that there hasn’t been improvement on some fronts, but only to show that human progress is not linear and that societal regression can easily take place under a socio-economic order designed to enhance the power of a few at the expense of society as a whole, which is indeed the trademark of neoliberal capitalism. Nations rise and fall, and even our ability to use reason does not necessarily increase with time and with the further advance of science.

As a matter of fact, a good argument can be made that we live today in a new age of unreason.

Science is still rejected by many people, objectivity and truth have become contested terms, and we are delaying the end of the fossil fuel age because we are accustomed to doing things in a particular way. Economics, politics, and psychology are all at work behind humanity’s apparent inability or unwillingness to alter course with regard to energy production and consumption even though we know that fossil fuels are destroying the environment by producing large amounts of greenhouse gases which trap hear and raise temperature across the globe.

Of course, capitalism itself is a highly irrational system for meeting human needs and wants; yet it’s been around for more than 500 years and predictions of a post-capitalist future knocking on our door should be taken with a grain of salt. Capitalism has demonstrated an uncanny ability to evolve, and can easily co-exist with different types of regimes, ranging from social-democracy to dictatorship. But now it is ruining the Earth, and unless we can this irrational economic system and, above all else, do away with its addiction to fossil fuels, the collapse of civilized social order is a near certainty. Then the floodgates of barbarism will be wide open.

–

C.J. Polychroniou is a political economist/political scientist who has taught and worked in numerous universities and research centers in Europe and the United States. Currently, his main research interests are in European economic integration, globalization, climate change, the political economy of the United States, and the deconstruction of neoliberalism’s politico-economic project. He has published scores of books, and his articles have appeared in a variety of journals, magazines, newspapers and popular news websites. Many of his publications have been translated into several foreign languages, including Arabic, Croatian, Dutch, French, Greek, Italian, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish and Turkish. His latest books are Optimism Over Despair: Noam Chomsky On Capitalism, Empire, and Social Change, an anthology of interviews with Chomsky originally published at Truthout and collected by Haymarket Books; Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (with Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin as primary authors); and The Precipice: Neoliberalism, the Pandemic, and the Urgent Need for Radical Change, an anthology of interviews with Chomsky originally published at Truthout and collected by Haymarket Books (scheduled for publication in June 2021).

- Page 2 of 2

- previous page

- 1

- 2