22. Dezember 1943 ~ Und vielleicht bringt es uns Hoffnung

22. Dezember 1943

22. Dezember 1943

Schon 2 Tage ist Hans weg, morgen erwarte ich Post, aber bringt sie günstige Berichte, ob Guus und ihre Mutter wieder zu Hause sind? Ach, es wird wohl nicht so sein. Optimistisch Denken hat man verlernt, die bittere, harte Wirklichkeit zeigt es täglich wie streng die Herren sind. Ach, die armen Menschen! Hans und sein Mädchen sind mir nicht aus dem Sinn, im(m)er denke ich an sie. Warum hat man Haussuchung getan? Warum hat man den Rundfunk nicht weggetan oder wenigstens wie so viele gut verstopft?

So etwas ist Leichtsinn, und fast nicht gut zu sprechen; welch ein Drama spielte sich ab, da man die Frauen mitnahm? Wenn sie nur bald zurückkommen, der Mann bekommt sicher eine lange Strafe, Hans läuft nun einsam herum, ist die Anwesenheit seiner Liebsten täglich gewöhnt, sitzt in Sorge wie es ihr geht, ist gebunden, kann nicht helfen, kein Bericht kommt durch. Ach, ich habe so Mitleid.

Weinen kann ich nicht mehr, bloß als Hans weg war, weinte ich bitterlich, so unsagbar Leid tut mir alles, und noch muss man froh sein, dass er nicht an dem Abend dorten war, was doch gut möglich gewesen wäre. Alles ist Zufall. Aber Guus, die meinen Sohn lieb hat und die ich nicht persönlich kenne, ist mir doch ans Herz gewachsen, denn was sie tut ist so edel, obwohl an der anderen Seite so gefährlich, und tut mir die arme Mutter leid, die nun um Mann und vielleicht ums Kind mit ins Unglück gezogen ist. Aber es ist ja ein Glück, dass es solche mutige Menschen gibt, sonst bekämen all die Untergetauchten, Christen wie Juden keine Hilfe. Ein Kassenbuch hat mir das Töchterchen heute mitgebracht, das ich als Tagebuch benutze, andere Hefte sind nicht mehr so zu bekommen.

In Russland hat die Winteroffensive eingesetzt, an 5 Fronten wird heftig und schwer gekämpft, 20 -30.000 deutsche Soldaten hat es in der letzten Woche gekostet. Flieger bombardierten in den letzten Nächten Frankfurt, Mannheim. Nordwestdeutschland, Frankreich und in einigen Tagen ist das Heiligste Fest im Jahr, Weihnachten, das Friede auf Erden bringen soll. Friede! Welcher Klang! Ein Lied ohne Wert ist es geworden, die Menschen sind Tiere geworden, die sich ermorden, und die Welt geht zugrunde. In Russland hat man 4 Missetäter verurteilt, die tausende Menschen in Charkow töten ließen, vor 40.000 Zuschauer erhing man sie öffentlich am Galgen.

Mittelalterliche Zustände, aber darin leben wir, allein die Technik ist modern, und daher ist die Mordlust noch tausend Mal schlimmer.

Bestien sind die Völker unter einander. Wenn nur die Tage eher vergingen! Monat Dezember dauert so lange. Ach, das neue Jahr, was wird es bringen? Wenn wir nur gesund, und aus den Händen der Feinde bleiben! So schwer ist diese Isolierung, das erste Jahr ging, aber nun, wo wir übermorgen schon 16 Monate lang hier sind, ist es mir, als könnte ich es nicht mehr lange aushalten. Und doch muss es, der Wille vermag so viel, auch das Kind rebelliert oft, aber an Tagen, wo sie sich dem Schicksal unterwirft, tröstet sie sich mit Lesen, einer Arbeit, Zeichnen, etwas Sprachenunterricht.

So gehen die Tage vorbei, gestern war der kürzeste Tag, nun gehen wir wieder dem Vorjahr entgegen und vielleicht bringt es uns Hoffnung.

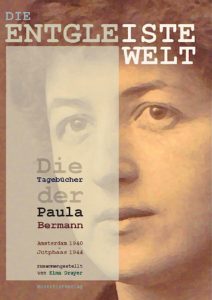

Paula Bermann – Die entgleiste Welt.Die Tagebücher. Amsterdam 1940 – Jutphaas 1944. Musketier-Verlag, Bremen. ISBN 9783946635673

Don’t Dismiss Marx. His Critique Of Colonialism Is More Relevant Than Ever

Marcello Mustro – Photo: York University

12-15-2023 Contrary to liberal misinterpretations, Marx was a fierce critic of colonialism, says Marxist scholar Marcello Musto.

During the last couple of decades, we have been witnessing a resurgence of interest in the thought and work of Karl Marx, author of major philosophical, historical, political and economic works — and of course, of The Communist Manifesto, which is perhaps the most popular political manifesto in the history of the world. This resurgence is largely due to the devastating consequences of neoliberalism around the world — unprecedented levels of economic inequality, social decay and popular discontent, as well as intensifying environmental degradation bringing the planet ever closer to a climate precipice — and the inability of the formal institutions of liberal democracy to solve this growing list of societal problems. But is Marx still relevant to the socio-economic and political landscape that characterizes today’s capitalist world? And what about the argument that Marx was Eurocentric and had little or nothing to say about colonialism?

Marcello Musto, a leading Marxist scholar, and professor of sociology at York University in Toronto, Canada, who has been a part of the revival of interest in Marx, contends in an exclusive interview for Truthout that Marx is still very much relevant today and debunks the claim that he was Eurocentric. In the interview that follows, Musto argues that Marx was, in fact, intensely critical of the impact of colonialism.

C.J. Polychroniou: In the last decade or so there has been renewed interest in Karl Marx’s critique of capitalism among leftist public intellectuals. Yet, capitalism has changed dramatically since Marx’s time and the idea that capitalism is fated to self-destruct because of contradictions that arise from the workings of its own logic no longer commands intellectual credibility. Moreover, the working class today is not only much more complex and diverse than the working class of the industrial revolution but has also not fulfilled the worldwide historical mission envisioned by Marx. In fact, it was such considerations that gave rise to post-Marxism, a fashionable intellectual posture from the 1970s to the 1990s, which attacks the Marxist notion of class analysis and underplays the material causes for radical political action. But now, it seems, there is a return once again to the fundamental ideas of Marx. How should we explain the renewed interest in Marx? Indeed, is Marx still relevant today?

Marcello Musto: The fall of the Berlin Wall was followed by two decades of conspiracy of silence on Marx’s work. In the 1990s and 2000s, the attention toward Marx was extremely scarce and the same can be said for the publication, and discussion, of his writing. Marx’s work — no longer identified with the odious function of instrumentum regni of the Soviet Union — became the focus of a renewed global interest in 2008, after one of the biggest economic crises in the history of capitalism. Prestigious newspapers, as well as journals with wide readerships, described the author of Capital as a farsighted theorist, whose topicality received confirmation one more time. Marx became, almost everywhere, the theme of university courses and international conferences. His writings reappeared on bookshop shelves, and his interpretation of capitalism gathered increasing momentum.

In the last few years, there has also been a reconsideration of Marx as a political theorist and many authors with progressive views maintain that his ideas continue to be indispensable for anyone who believes it is necessary to build an alternative to the society in which we live. The contemporary “Marx revival” is not confined only to Marx’s critique of political economy, but also open to rediscovering his political ideas and sociological interpretations. In the meantime, many post-Marxist theories have demonstrated all their fallacies and ended up accepting the foundations of the existing society — even though the inequalities that tear it apart and thoroughly undermine its democratic coexistence are growing in increasingly dramatic forms.

Certainly, Marx’s analysis of the working class needs to be reframed, as it was developed on the observation of a different form of capitalism. If the answers to many of our contemporary problems cannot be found in Marx, he does, however, center the essential questions. I think this is his greatest contribution today: he helps us to ask the right questions, to identify the main contradictions. That seems to me to be no small thing. Marx still has so much to teach us. His elaboration helps us better understand how indispensable he is in rethinking an alternative to capitalism — today, even more urgently than in his time.

Marx’s writings include discussions of issues, such as nature, migration and borders, which recently have received renewed attention. Can you briefly discuss Marx’s approach to nature and his take on migration and borders?

Marx studied many subjects — in the past often underestimated, or even ignored, by his scholars — which are of crucial importance for the political agenda of our times. The relevance that Marx assigned to the ecological question is the focus of some of the major studies devoted to his work over the past two decades. In contrast to interpretations that reduced Marx’s conception of socialism to the mere development of productive forces (labor, instruments and raw material), he displayed great interest in what we today call the ecological question. On repeated occasions, Marx argued that the expansion of the capitalist mode of production increases not only the exploitation of the working class, but also the pillage of natural resources. He denounced that “all progress in capitalist agriculture is a progress in the art, not only of robbing the worker but of robbing the soil.” In Capital, Marx observed that the private ownership of the earth by individuals is as absurd as the private ownership of one human being by another human being.

Marx was also very interested in migration and among his last studies are notes on the pogrom that occurred in San Francisco in 1877 against Chinese migrants. Marx railed against anti-Chinese demagogues who claimed that the migrants would starve the white proletarians, and against those who tried to persuade the working class to support xenophobic positions. On the contrary, Marx showed that the forced movement of labor generated by capitalism was a very important component of bourgeois exploitation and that the key to combating it was class solidarity among workers, regardless of their origins or any distinction between local and imported labor.

One of the most frequently heard objections to Marx is that he was Eurocentric and that he even justified colonialism as necessary for modernity. Yet, while Marx never developed his theory of colonialism as extensively as his critique of political economy, he condemned British rule in India in the most unequivocal terms, for instance, and criticized those who failed to see the destructive consequences of colonialism. How do you assess Marx on these matters?

The habit of using decontextualized quotations from Marx’s work dates much before Edward Said’s Orientalism, an influential book that contributed to the myth of Marx’s alleged Eurocentrism. Today, I often read reconstructions of Marx’s analyses of very complex historical processes that are outright fabrications.

Already in the early 1850s, in his articles (contested by Said) for the New-York Tribune — a newspaper with which he collaborated for more than a decade — Marx had been under no illusion about the basic characteristics of capitalism. He well knew that the bourgeoisie had never “effected a progress without dragging individuals and people through blood and dirt, through misery and degradation.” But he had also been convinced that, through world trade, development of the productive forces and the transformation of production into something scientifically capable of dominating the forces of nature, “bourgeois industry and commerce [would create] these material conditions of a new world.” These considerations reflected no more than a partial, ingenuous vision of colonialism held by a man writing a journalistic piece at barely 35 years of age.

Later, Marx undertook extensive investigations of non-European societies and his fierce anti-colonialism was even more evident. These considerations are all too obvious to anyone who has read Marx, despite skepticism in some academic circles that represent a bizarre form of decoloniality and assimilate Marx to liberal thinkers. When Marx wrote about the domination of England in India, he asserted that the British had only been able to “destroy native agriculture and double the number and intensity of famines.” For Marx, the suppression of communal landownership in India was nothing but an act of English vandalism, pushing the native people backwards, certainly not forwards.

Nowhere in Marx’s works is there the suggestion of an essentialist distinction between the societies of the East and the West. And, in fact, Marx’s anti-colonialism — particularly his ability to understand the true roots of this phenomenon — contributes to the new contemporary wave of interest in his theories, from Brazil to Asia. Read more

Myanmar’s Instability Deepens As The World Watches Silently

John P. Ruehl – Source: Independent Media Institute

12-13-2023 Militant groups are increasingly threatening Myanmar’s military government. But other non-state actors, as well as China, are playing powerful roles in the divided country.

Myanmar’s stability has eroded significantly since the 2021 military coup. But the coordinated attack by multiple separatist and pro-democracy groups in October and November 2023 has seen military outposts, villages, border crossings, and other infrastructure overrun. While the Tatmadaw, Myanmar’s military, clings to control in central and coastal regions populated by the country’s ethnic majority, much of the country’s border areas are increasingly slipping into anti-government control.

This current turbulence is not an aberration but deeply rooted in Myanmar’s history. Since gaining independence from British rule in 1948, the country has grappled with what is commonly described as the world’s longest-running civil war. Initial experiments with democracy witnessed limited clashes between Myanmar’s central government and Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs.) Following a military coup in 1962 that established the junta, more EAOs emerged to challenge government power.

Infighting and splintering among EAOs, coupled with their growing antagonism toward the Burma Communist Party (BCP), itself waging a war on the central government, allowed the junta to implement fragile ceasefires in exchange for limited autonomy. By the end of the Cold War, democratic protests in 1988, the collapse of the BCP in 1989, and free elections in 1990 all suggested Myanmar was cautiously embracing a peaceful future.

Despite losing the elections in 1990, however, the junta did not relinquish power, drawing international condemnation. EAOs and other groups like the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), which split from the BCP, then continued their struggle for two decades until the junta ceded some powers to a civilian administration in 2011. Elections in 2015 and 2020 saw landslide victories for the National League for Democracy (NLD), as well as some progress toward reconciliation.

But in 2021, the Tatmadaw reestablished the junta and plunged the country back into destabilization, culminating in the 2023 autumn offensive by anti-junta forces. In addition to EOAs and a reorganized BCP, the junta has also been forced to contend with People’s Defense Forces (PDFs), loose armed organizations backed by the National Unity Government (NUG), set up by lawmakers and politicians in the aftermath of the coup. Additionally, the role of the Burman ethnic majority and grassroots civil defense forces in opposing the junta has also complicated its response to unrest.

The junta has proven adept at managing its restive elements before, and can also rely on its Border Guard Forces (BGFs) and other pro-government militia groups. But the broad swathes of Myanmar’s society fighting against it have made the junta’s traditional policy of divide and rule far less effective. Myanmar’s Acting President Myint Swe has said the country could “split into various parts”, prompting Myanmar military officials to retreat to the capital, Naypyidaw, a planned city completed in 2012 that effectively serves as a fortress located near the most restive regions.

China’s role in Myanmar has undergone significant shifts since the latter’s independence. Despite Chinese support for the BCP and other communist groups, Myanmar grew closer to China after its isolation from the West in the 1990s. Beijing supported the junta to stabilize Myanmar and prevent adversaries from establishing a foothold on China’s southern border. Other interests included maintaining access to Myanmar’s raw materials and natural resources, as well as infrastructure development to turn Myanmar into a strategic gateway to the Bay of Bengal through the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC), part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

China maintained ties to the junta, democracy advocates, and ethnic groups from 2011 to 2021. However, the 2021 coup disrupted development projects and led to attacks on Chinese-run facilities by rebel groups, and the junta’s inability to protect infrastructure exacerbated historical tension between it and Beijing. Four Chinese civilians were killed in 2015 after a Myanmar military airstrike hit across the border into Yunnan, while the junta burned down a Chinese-owned factory and killed Chinese and Myanmar civilians in 2021.

China’s ongoing support to some militia groups, such as the United Wa State Army (UWSA) and MNDAA, provides Beijing leverage over the junta and a say in the ceasefire processes. Chinese firms also often work with armed groups in “special economic zones” near the border, and some of the anti-junta groups regularly cross the border to China to escape the junta and its proxy forces. Beijing’s tacit approval of their activities may also be partially fueled by wariness that rebel groups were becoming closer to the U.S. prior to the new offensive.

Beijing has nonetheless attempted to sustain a balancing act, arresting a UWSA deputy military chief in October 2023 and initially ignoring calls for assistance from the rebels after the launch of their offensive. But following the steady string of defeats suffered by the junta, China has since altered its outlook. China’s affiliates now form some of the most powerful groups operating in Myanmar, and China’s foreign ministry has called for a ceasefire.

Myanmar’s porous borders have not only allowed armed groups to flourish but also facilitated the expansion of organized crime networks. Increased cooperation between militant and criminal groups in recent decades, known as the terror-crime nexus, has elevated the power of these groups worldwide.

American efforts to counter communism inadvertently helped develop drug networks in Myanmar during the early Cold War, while transnational organized crime in Southeast Asia burgeoned in the 21st Century. The COVID-19 pandemic further established Myanmar as a hub of criminal activity, expanding the funding networks available to the country’s armed groups. Both local and international criminal networks operate in Myanmar’s special economic zones, engaging in human and wildlife trafficking, slavery, cybercrimes, money laundering, communication fraud, illegal casinos, and online gambling centers.

The relationships between these entities and governments are intricate, with shifting alliances commonplace. Beijing and transnational Chinese gangs play central roles in Myanmar’s heightened criminal activity. The junta has also had close ties to criminal networks for decades, and since the 2021 coup has become increasingly reliant on criminal activity to finance itself and offset international isolation.

China, while entangled in Myanmar’s criminal underworld, has grown steadily more concerned with rising illicit activity on its border with Myanmar and the willing and unwilling participation of Chinese citizens. China’s signals to the junta to address the forced-labor networks since May 2023 went unheeded, leading to China issuing arrest warrants for junta allies and the UWSA to raid online scam compounds and trafficked labor centers in border regions. Read more

Dubai Is A Fitting Host For The Climate Circus

Sonali Kolhatkar

12-12-2023 A host nation that promises progress but relies on regressive policies is revealing just how seriously fossil fuel interests have coopted UN climate talks.

In January 2023, nearly a year before the latest United Nations climate conference began, there was deep concern and alarm over the head of one of the world’s largest oil companies being appointed president of the COP28 summit. The climate talks taking place in December 2023 were hosted by the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and overseen by Sultan Al Jaber, a man who happens to be in charge of the UAE’s national oil company Abu Dhabi National Oil Company. It’s a fitting illustration of an old idiom that the fox is in charge of the hen house.

Al Jaber’s appointment was such a clear conflict of interest that a group of United States lawmakers, including House Representatives Barbara Lee, Rashida Tlaib, and Jamaal Bowman, and Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, sent a scathing letter on January 26th denouncing it. “Having a fossil fuel champion in charge of the world’s most important climate negotiations would be like having the CEO of a cigarette conglomerate in charge of global tobacco policy,” wrote the lawmakers.

Their warning fell on deaf ears and yet their fears proved to be correct months later when The Guardian newspaper published Al Jaber’s revealing remarks made at a November 2023 online climate meeting. Climate justice leader and former President of Ireland, Mary Robinson, rightly pointed out that the climate crisis was hurting women and children, and that Al Jaber had the power to do something about it. The oil company head angrily retorted that her comments were “alarmist,” and asserted that, “There is no science out there, or no scenario out there, that says that the phase-out of fossil fuel is what’s going to achieve 1.5C.”

He went on to say, “Show me the roadmap for a phase-out of fossil fuel that will allow for sustainable socioeconomic development, unless you want to take the world back into caves.” Sounding defensive and cornered, Al Jaber added, “Show me the solutions. Stop the pointing of fingers. Stop it.”

Adding (fossil) fuel to the fire, the BBC published an exposé days before COP28 began revealing that “The United Arab Emirates planned to use its role as the host of UN climate talks as an opportunity to strike oil and gas deals.” UAE authorities did not deny the reports and instead responded with shocking hubris that “private meetings are private.”

Such shenanigans reveal the futility of relying on the UN’s annual COP meetings to phase out fossil fuels in order to stave off catastrophic climate change. Whereas earlier COP meetings fixated on the goal of “net zero emissions”—a phrase that climate activists rightly denounced as greenwashing and propaganda—the favorite phrase at this year’s COP28 appeared to be a “phase down” of fossil fuels.

The idea is that oil and gas producers may consider, someday in the far future, to start producing fewer fossil fuels than they do now. “Phase down” is a clever dilution of “phase out.” It is a sleight of hand intended to assuage concern over the warming climate all while remaining on a path to climate destruction.

The first draft of the COP28 agreement spelled out the two terms as interchangeable, referring to a “phasedown/out.” Al Jaber reflected this equation of two different words even as he sought to maintain his credentials as head of COP28, saying that he has maintained “over and over that the phase-down and the phase-out of fossil fuel is inevitable.”

That Al Jaber would engage in trickery to protect fossil fuels is hardly surprising given his role as head of the Abu-Dhabi-based oil firm. In his leaked remarks to Robinson, he proclaimed that phasing out oil and gas was not feasible, “unless you want to take the world back into caves.”

But it is precisely the continued use of fossil fuels that may take us back to the stone age. We may all be living in caves someday, seeking high ground from the rising waters of the warming oceans, all while Al Jaber and his ilk are ensconced in the luxury bunkers of the wealthy.

It is an image that reflects the reality of Dubai, a gleaming, futuristic city where the Emirates pays lip service to climate progress as host of COP28, while simultaneously conspiring to secure oil and gas deals on the side. It’s a city that is defined by yet another idiom: trying to have your cake and eat it too.

I know, because I was born and raised in Dubai, a child of Indians who emigrated in 1970 to a land known as the Trucial Sheikhdoms—one year before they formally emerged as a single sovereign nation called the United Arab Emirates. My parents’ tenure in the UAE was older than the nation itself and while they toiled for more than 50 years as part of an immigrant workforce that outnumbers Emiratis 9 to 1, they were never afforded citizenship, as were none of their three children born there.

The Emirates, with the blessing of its former colonial master Britain, and its newer imperial partners, the U.S. and Israel, has presided over an oil-funded project fueled by exploited immigrant labor to emerge as one of the most important trading hubs in the world: a seductive tourist trap dotted by massive shopping malls and billboards beneath which teeming labor campsinvisibly keep the wheels of capitalism turning. It touts a liberalism that allows women to work, drive, and even hold limited leadership, all while suppressing the rights of low-wage female domestic workers. It pledges sustainability while marketing itself to global investors.

It is hypocrisy manifested; a pretty façade of a promising future built on an age-old model of serfdom, a nation that celebrates the freedom to consume, but clamps down on the freedom to speak. In other words, it is a capitalist’s wet dream. What better place for fossil fuel promoters to pretend they care about the future of the planet?

The COP meetings have been a disastrous distraction from the urgent need to end fossil fuel production and consumption. Even Christiana Figueres, former executive secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, who is considered the architect of the 2015 Paris climate accord, is so disgusted by the state of proceedings that she called the COP “a circus.”

Having Dubai host the largest annual international climate gathering is a desperate bid by a dying industry to maintain relevance. Energy forecasting predictions point to a grim future for petrostates like the UAE. It’s no wonder Al Jaber has publicly tied himself into knots of contradictions. His nation’s future depends on the continued flow of oil and gas, while our world’s future depends on an immediate termination of the poisonous fuels.

By Sonali Kolhatkar

Author Bio:

Sonali Kolhatkar is an award-winning multimedia journalist. She is the founder, host, and executive producer of “Rising Up With Sonali,” a weekly television and radio show that airs on Free Speech TV and Pacifica stations. Her most recent book is Rising Up: The Power of Narrative in Pursuing Racial Justice (City Lights Books, 2023). She is a writing fellow for the Economy for All project at the Independent Media Institute and the racial justice and civil liberties editor at Yes! Magazine. She serves as the co-director of the nonprofit solidarity organization the Afghan Women’s Mission and is a co-author of Bleeding Afghanistan. She also sits on the board of directors of Justice Action Center, an immigrant rights organization.

Source: Independent Media Institute

Credit Line: This article was produced by Economy for All, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

Will COP28 End Up As The Greatest Flop In Global Climate Diplomacy Thus Far?

James K. Boyce – Photo: jameskboyce.com

12-11-2023 Environmental economist James K. Boyce analyzes the roadblocks to climate action at the COP28 climate summit.

Global climate summits have rarely produced tangible results. More than anything, they have proven to be nothing less than platforms for verbose empty promises and extensive lobbying for the fossil fuel industry. COP28, currently underway in Dubai, may very well end up as the greatest flop so far in global climate diplomacy. Aside from the fact that it is presided over by the CEO of the United Arab Emirates’ state-run oil company, global leaders like Joe Biden and Xi Jinping have decided to skip the conference.

In the exclusive interview for Truthout that follows, leading environmental economist James K. Boyce discusses the main roadblocks to climate action facing COP28 and argues for the need to introduce global carbon pricing as an essential policy towards decarbonization. Boyce is emeritus professor of economics and senior fellow at the Political Economy Research Institute (PERI) at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. He is the author of numerous books, including The Political Economy of the Environment (1972), Economics for People and the Planet: Inequality in the Era of Climate Change (2019) and The Case for Carbon Dividends(2019).

C. J. Polychroniou: COP28 President and United Arab Emirates climate chief Sultan Al Jaber said there is “no science” behind demands for phasing out fossil fuels; in addition, he expressed doubts that there is a road map for the phase out of fossil fuels that would allow sustainable development, “unless [we] want to take the world back into caves.” Isn’t this already sufficient evidence that COP28 will be yet another global climate summit flop? Indeed, why would any country serious about tackling the climate crisis agree to a global climate summit that is hosted by a global leader in the oil and gas industry and whose vested interests are therefore in a product that puts the whole planet at risk? Be that as it may, what are the biggest roadblocks to climate action facing COP28?

James K. Boyce: Look, there is a reason these things are called negotiations. And there is something to be said for taking the fight to the heart of the beast.

There are powerful people who profit greatly from fossil fuel extraction. We’re talking here about big corporations as well as oil fiefdoms. But the vast majority of us, and the generations to come, will benefit far more by phasing them out. So there are opposing interests at play, and the issue is who will prevail.

It is ironic, of course, to see a climate summit happening in the Emirates. But the big roadblock isn’t where the summit is held. It is the vested interests worldwide who want to keep us hooked on fossil fuels as long as they can. This is a transnational alliance among people whose commitments to any particular place are weaker than what bonds them together: the pursuit of self-interest. Rising temperatures could make the Emirates uninhabitable in coming decades, but billionaires can buy safe landings in a more salubrious place. It is the people around the world who are more attached to the places they live and work, people who cannot easily move, who are at greatest risk.

It is important to realize that the climate crisis is not an all-or-nothing phenomenon. We have already entered an era of crisis, and this will intensify in the years ahead. The real question is how bad it will get. And that depends on what we do today. There is never a point where all is lost, because it can always get worse. Nothing could be more irresponsible than to throw up our hands and say, “Game over.”

The head of the International Monetary Fund said at the COP28 climate summit that decarbonization cannot proceed without carbon pricing. Could carbon pricing policies that incentivize reduced use of fossil fuels do enough to hold global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius? The projections say that fossil fuels — oil, coal and natural gas — will continue to provide the bulk of our energy needs for the foreseeable future. So, how effective can a carbon tax be in transforming pathways to reach zero emissions?

She did not say that decarbonization cannot proceed at all without carbon pricing. What she said was that it will not happen fast enough. She is right, but only partially right: We need a carbon price as part of the policy mix, but not just any carbon price. The price must be anchored to a hard emissions-reduction trajectory.

As I have written elsewhere (here, for example), there is a straightforward way to do this: Any country that is serious about tackling climate change could put a strict limit on the amount of fossil carbon — carbon embodied in oil, natural gas and coal — that is allowed to enter its economy. This limit would decline — the cap would tighten — year by year, on a path to net-zero emissions by a specific date, say 2050.

A hard limit is different from a carbon tax. A tax puts a price on carbon and lets the quantity of emissions adjust. A hard limit sets the quantity and lets the price of fossil fuels adjust. The carbon price that results from this limit drives a wedge between the price paid by fossil fuel users and the price received by fossil fuel producers. The first goes up as the supply of fossil fuels is curtailed, while the second goes down as the market contracts.

The higher price to consumers of fossil fuels is not a bug of the policy, it’s a feature: It helps steer the consumption and investment decisions of firms and individuals away from use of fossil fuels toward alternative fuels and energy efficiency. Like it or not, prices matter. They matter a lot. Most investment in the world economy — about three-quarters of the total — is private, not public. And private investment responds above all to price signals.

The problem, of course, is that higher fuel prices on their own would hit consumers, including working families who already struggle to make ends meet. For this reason, many politicians — even those who are not on the take from the fossil fuel lobby — have been reluctant to embrace carbon pricing in any form. But there is a straightforward way to solve this problem, too.

First, auction off the permits to bring fossil carbon into the economy. Don’t give them away, as often is done in “cap-and-trade” systems. For fossil fuel suppliers, the permit price becomes part of the cost of doing business. It’s passed on to final consumers in the prices of goods and services in proportion to the amount of fossil carbon used in their production and distribution. Read more

Why The World’s Most Popular Herbicide Is A Public Health Hazard

Caroline Cox – Photo: LinkedIn

Known by its brand name Roundup, glyphosate is a clear and present danger to human health.

Glyphosate, known by its famous brand name, Roundup, is a widely used herbicide (a pesticide designed to kill plants). It is a broad-spectrum herbicide that kills or damages all plant types: grasses, perennials, vines, shrubs, and trees. Glyphosate has been sold as an herbicide since 1974. Its use dramatically increased in the 21st century as its patents expired and genetically modified crop varieties that tolerated exposure to glyphosate became popular.

Experts now believe it is the “most heavily” used herbicide globally. In 2015, the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified glyphosate as a probable human carcinogen.

Glyphosate: Widespread Use and Exposure

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimated glyphosate usage in 2019—based on data collected between 2012 and 2016—and concluded that almost 300 million acres of farmland were treated with about 280 million pounds of glyphosate yearly. Another 24 million pounds of the herbicide is used every year in home yards, roadways, forestry, and turf, according to a 2020 analysis by the agency.

Given this enormous use of glyphosate in the United States, it is perhaps unsurprising that exposure to it is widespread. A unit of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention did the largest and most comprehensive study to determine glyphosate exposure using urine collected from a sample of Americans selected between 2013 and 2014 to accurately represent the entire population. Researchers found that more than 80 percent of participants, who were six years and older, had been exposed to glyphosate. In discussing the results, the CDC suggested that food was an important source of exposure to the chemical. “Participants who had not eaten for eight or more hours had lower levels of glyphosate in their urine.”

The Salinas Study: Liver Diseases and Diabetes

A growing number of studies link exposure to glyphosate with various human health problems other than the cancer hazard that IARC evaluated. Typically classified as epidemiology, this research does not formally determine cause and effect but is more realistic and often more compelling than research done using laboratory animals or cell cultures.

One example of an epidemiology study comes from the agricultural town of Salinas, California. Starting in 1999, the University of California, Berkeley, scientists recruited pregnant mothers and then their children as volunteer participants in a study called the Center for the Health Assessment of Mothers and Children of Salinas (CHAMACOS), which was conducted over a period of more than 20 years. These “480 mother-child duos” mostly belonged to farmworker families in the Salinas area. The mothers provided their blood and urine samples and other health information during pregnancy, while the samples from children were collected when they were 5, 14, and then 18 years old. All of this data was used to answer essential questions about glyphosate exposure.

The CHAMACOS study compared teens with higher-than-average exposure to glyphosate as children to those with lower exposure. Teens with higher exposure to glyphosate and its primary breakdown product, aminomethylphosphonic acid (AMPA), were more likely to show signs of liver inflammation, meaning they had a higher risk of developing liver disease. They were also more likely to have metabolic syndrome (high blood pressure, high blood sugar, low levels of “good” cholesterol, and several other health problems), which could make them more susceptible to serious health concerns such as liver cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes, later in life.

The study had several other interesting results. In the early years of the study (2000-2002), glyphosate exposures in children were infrequent and low. Most participants did not have glyphosate in their bodies. This changed dramatically as time went on. Glyphosate and AMPA were found in 80 to 90 percent of the 14-year-old participants. The researchers note that this mirrors the national and global increase in glyphosate use.

In addition, the Salinas study showed that glyphosate exposures in this agricultural farmworker community were similar to exposures across the country in people who were not farmworkers. According to the researchers, this suggests that the primary source of glyphosate exposure was food, concluding that “diet was a major source of glyphosate and AMPA exposure among… study participants… as indicated by higher urinary glyphosate or AMPA concentrations among those who ate more cereal, fruits, vegetables, bread, and in general, carbohydrates.”

American Women: Pregnancy Problems

Another example of epidemiology showing glyphosate hazards comes from a study of pregnant women living in California, Minnesota, New York, and Washington. This study found that more than 90 percent of these women were exposed to glyphosate and that higher exposures to glyphosate and AMPA during the second trimester were linked to shorter-than-normal pregnancies. The study participants represented all American pregnant women in terms of race, ethnicity, economic status, and urban versus suburban families. The report concluded that exposure to glyphosate “may impact reproductive health by shortening length of gestation.”

Canadian Study: Glyphosate in Food

A detailed evaluation of glyphosate exposure comes from a study of about 2,000 pregnant women in 10 cities across Canada between 2008 and 2011. Based on urine analysis and questionnaires, the researchers concluded that food was a more likely source of glyphosate exposure than household pesticide use or pesticide drift. The foods linked to higher glyphosate exposures were spinach, whole grain bread, soy and rice beverages, and pasta. The strongest link was “between consumption of whole grain bread and higher urinary glyphosate concentrations.” Read more