How Elite Infighting Made The Magna Carta

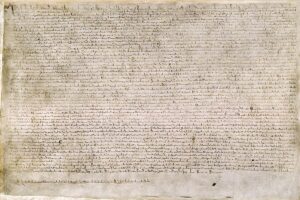

Magna Carta Libertatum 1215 – British Library

04-06-2024 ~ Although the Magna Carta typically is depicted as the birth of England’s fight to create democracy, the 13th-century struggle was to establish what would become the House of Lords, not the House of Commons.

The papacy’s role as organizer of the Crusades empowered it to ask for—indeed, to demand—tithes from churches and royal tax assessments from realms ruled by the warlord dynasties it had installed and protected. England’s nobility and clergy pressed for parliamentary reform to block King John and his son Edward III from submitting to Rome’s demands to take on debts to finance its crusading and fights against Germany’s kings. Popes responded by excommunicating reformers and nullifying the Magna Carta again and again during the 13th century.

The Burdensome Reign of King John

John I (1199-1216) was dubbed “Lackland” because, as Henry II’s fourth and youngest son, he was not expected to inherit any land. On becoming his father’s favorite, he was assigned land in Ireland and France, which led to ongoing warfare after his brother Richard I died in 1199. This conflict was financed by loans that John paid by raising taxes on England’s barons, churches, and monasteries. John fought the French for land in 1202, but lost Normandy in 1204. He prepared for renewed war in France by imposing a tallage in 1207; as S.K. Mitchell details in his book on the subject, this was the first such tax for a purpose other than a crusade.

By the 13th century, royal taxes to pay debts were becoming regular, while the papacy made regular demands on European churches for tithes to pay for the Crusades. These levies created rising opposition throughout Christendom, from churches as well as the baronage and the population at large. In 1210, when John imposed an even steeper tallage, many landholders were forced into debt.

John opened a political war on two fronts by insisting on his power of investiture to appoint bishops. When the Archbishop of Canterbury died in 1205, the king sought to appoint his successor. Innocent III consecrated Stephen Langdon as his own candidate, but John barred Stephen from landing in England and started confiscating papal estates. In 1211 the pope sent his envoy, Pandulf Verraccio, to threaten John with excommunication. John backed down and allowed Stephen to take his position, but then collected an estimated 14 percent of church income for his royal budget over the next two years—£100,000, including Peter’s Pence.

Innocent sent Pandulf back to England in May 1213 to insist that John reimburse Rome for the revenue that he had withheld. John capitulated at a ceremony at the Templar church at Dover and reaffirmed the royal tradition of fealty to the pope. As William Lunt details in Financial Relations of the Papacy with England to 1327, John received England and Ireland back in his fiefdom by promising to render one thousand marks annually to Rome over and above the payment of Peter’s Pence, and permitted the pope to deal directly with the principal local collectors without royal intervention.

John soon stopped payments, but Innocent didn’t protest, satisfied with having reinforced the principle of papal rights over his vassal king. In 1220, however, the new pope “Honorius III instructed Pandulf to send the proceeds of the [tallage of a] twentieth, the census [penny poll tax] and Peter’s Pence to Paris for deposit with the Templars and Hospitallers.”[1] Royal control of church revenue was lost for good. The contributions that earlier Norman kings had sent to Rome were treated as having set a precedent that the papacy refused to relinquish. The clergy itself balked at complying with papal demands, and churches paid no more in 1273 than they had in 1192.

The barons were less able to engage in such resistance. Historian David Carpenter calculates that their indebtedness to John for unpaid taxes, tallages, and fines rose by 380 percent from 1199 to 1208. And John became notorious for imposing fines on barons who opposed him. That caused rising opposition from landholders—the fight that Richard had sought to avoid. The Exchequer’s records enabled John to find the individuals who owed money and to use royal fiscal claims as a political lever, by either calling in the debts or agreeing to “postpone or pardon them as a form of favor” for barons who did not oppose him.

John’s most unpopular imposition was the scutage fee for knights to buy exemption from military service. Even when there was no actual war, John levied scutage charges eleven times during his 17-year reign, forcing many knights into debt. Rising hostility to John’s campaign in 1214 to reconquer his former holdings in Normandy triggered the First Barons’ War (1215-1217) demanding the Magna Carta in 1215.

Opposition was strongest in the north of England, where barons owed heavy tax debts. As described in J.C. Holt’s classic study The Northeners, they led a march on London, assembling on the banks of the Thames at Runnymede on June 15, 1215. Although the Archbishop of Canterbury, Stephen Langdon, helped negotiate a truce based on a “charter of liberties,” a plan for reform between John and the barons that became the Magna Carta, the “rebellion of the king’s debtors” led to a decade-long fight, with the Magna Carta being given its final version under the teenaged Henry III in 1225.

Proto-Democratic Elements of the Magna Carta

There were proto-democratic elements in the Charter, most significantly the attempt to limit the king’s authority to levy taxes without the consent of a committee selected by the barons. The concept of “no taxation without representation” appears in the original Chapter 12: “No scutage or aid is to be levied in our kingdom, save by the common counsel of our kingdom,” and even then, only to ransom the king or for specified family occasions.

The linkage between debt, interest accruals, and land tenure was central to the Charter. Chapter 9 stated that debts should be paid out of movable property (chattels), not land. “Neither we [the king] nor our bailiffs are to seize any land or rent for any debt, for as long as the chattels of the debtor suffice to pay the debt.” Land would be forfeited only as a last resort, when sureties had their own lands threatened with foreclosure. And under the initial version of the Charter, debts were only to be paid after appropriate living expenses had been met, and no interest would accrue until the debtor’s heirs reached maturity.

Elite Interests in the Charter

The Magna Carta typically is depicted as the birth of England’s fight to create democracy. It was indeed an attempt to establish parliamentary restraint on royal spending, but the barons were acting strictly in their own interest. The Charter dealt with breaches by the king, but “no procedure was laid down for dealing with breaches by the barons.” In Chapter 39 they designated themselves as Freemen, meaning anyone who owned land, but that excluded rural villeins and cottagers. Local administration remained corrupt, and the Charter had no provisions to prevent lords from exploiting their sub-tenants, who had no voice in consenting to royal demands for scutages or other aids.

The 13th-century fight was to establish what would become the House of Lords, not the House of Commons. Empowering the nobility against the state was the opposite of the 19th-century drive against the landlord class and its claims for hereditary land rent. What was deemed democratic in Britain’s 1909/10 constitutional crisis was the ruling that the Lords never again could reject a House of Commons revenue act. The Commons had passed a land tax, which the House of Lords blocked. That fight against landlords was the opposite of the barons’ fight against King John.

Note:

1. William Lunt, “Financial Relations of the Papacy with England to 1327. (Studies in Anglo-Papal Relations during the Middle Ages, I.),” (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Mediaeval Academy of America, 1939) pp. 597-598 and pp. 58-59.

By Michael Hudson

Author Bio:

Michael Hudson is an American economist, a professor of economics at the University of Missouri–Kansas City, and a researcher at the Levy Economics Institute at Bard College. He is a former Wall Street analyst, political consultant, commentator, and journalist. You can read more of Hudson’s economic history on the Observatory.

Source: Human Bridges

Credit Line: This article was produced by Human Bridges.

The Unremarkable Death Of Migrants In The Sahara Desert

Vijay Prashad

04-06-2024 ~ Sabah, Libya, is an oasis town at the northern edge of the Sahara Desert. To stand at the edge of the town and look southward into the desert toward Niger is forbidding. The sand stretches past infinity, and if there is a wind, it lifts the sand to cover the sky. Cars come down the road past the al-Baraka Mosque into the town. Some of these cars come from Algeria (although the border is often closed) or from Djebel al-Akakus, the mountains that run along the western edge of Libya. Occasionally, a white Toyota truck filled with men from the Sahel region of Africa and from western Africa makes its way into Sabah. Miraculously, these men have made it across the desert, which is why many of them clamber out of their truck and fall to the ground in desperate prayer. Sabah means “morning” or “promise” in Arabic, which is a fitting word for this town that grips the edge of the massive, growing, and dangerous Sahara.

For the past decade, the United Nations International Organization of Migration (IOM) has collected data on the deaths of migrants. This Missing Migrants Project publishes its numbers each year, and so this April, it has released its latest figures. For the past ten years, the IOM says that 64,371 women, men, and children have died while on the move (half of them have died in the Mediterranean Sea). On average, each year since 2014, 4,000 people have died. However, in 2023, the number rose to 8,000. One in three migrants who flee a conflict zone die on the way to safety. These numbers, however, are grossly deflated, since the IOM simply cannot keep track of what they call “irregular migration.” For instance, the IOM admits, “[S]ome experts believe that more migrants die while crossing the Sahara Desert than in the Mediterranean Sea.”

Sandstorms and Gunmen

Abdel Salam, who runs a small business in the town, pointed out into the distance and said, “In that direction is Toummo,” the Libyan border town with Niger. He sweeps his hands across the landscape and says that in the region between Niger and Algeria is the Salvador Pass, and it is through that gap that drugs, migrants, and weapons move back and forth, a trade that enriches many of the small towns in the area, such as Ubari. With the erosion of the Libyan state since the NATO war in 2011, the border is largely porous and dangerous. It was from here that the al-Qaeda leader Mokhtar Belmokhtar moved his troops from northern Mali into the Fezzan region of Libya in 2013 (he was said to have been killed in Libya in 2015). It is also the area dominated by the al-Qaeda cigarette smugglers, who cart millions of Albanian-made Cleopatra cigarettes across the Sahara into the Sahel (Belmokhtar, for instance, was known as the “Marlboro Man” for his role in this trade). An occasional Toyota truck makes its way toward the city. But many of them vanish into the desert, a victim of the terrifying sandstorms or of kidnappers and thieves. No one can keep track of these disappearances, since no one even knows that they have happened.

Matteo Garrone’s Oscar-nominated Io Capitano (2023) tells the story of two Senegalese boys—Seydou and Moussa—who go from Senegal to Italy through Mali, Niger, and then Libya, where they are incarcerated before they flee across the Mediterranean to Italy in an old boat. Garrone built the story around the accounts of several migrants, including Kouassi Pli Adama Mamadou (from Côte d’Ivoire, now an activist who lives in Caserta, Italy). The film does not shy away from the harsh beauty of the Sahara, which claims the lives of migrants who are not yet seen as migrants by Europe. The focus of the film is on the journey to Europe, although most Africans migrate within the continent (21 million Africans live in countries in which they were not born). Io Capitano ends with a helicopter flying above the ship as it nears the Italian coastline; it has already been pointed out that the film does not acknowledge racist policies that will greet Seydou and Moussa. What is not shown in the film is how European countries have tried to build a fortress in the Sahel region to prevent migration northwards.

Open-Air Tomb

More and more migrants have sought the Niger-Libya route after the fall of the Libyan state in 2011 and the crackdown on the Moroccan-Spanish border at Melilla and Ceuta. A decade ago, the European states turned their attention to this route, trying to build a European “wall” in the Sahara against the migrants. The point was to stop the migrants before they get to the Mediterranean Sea, where they become an embarrassment to Europe. France, leading the way, brought together five of the Sahel states (Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger) in 2014 to create the G5 Sahel. In 2015, under French pressure, the government of Niger passed Law 2015-36 that criminalized migration through the country. G5 Sahel and the law in Niger came alongside European Union funding to provide surveillance technologies—illegal in Europe—to be used in this band of countries against migrants. In 2016, the United States built the world’s largest drone base in Agadez, Niger, as part of this anti-migrant program. In May 2023, Border Forensics studied the paths of the migrants and found that due to the law in Niger and these other mechanisms the Sahara had become an “open-air tomb.”

Over the past few years, however, all of this has begun to unravel. The coup d’états in Guinea (2021), Mali (2021), Burkina Faso (2022), and Niger (2023) have resulted in the dismantling of G5 Sahel as well as the demand for the removal of French and U.S. troops. In November 2023, the government of Niger revoked Law 2015-36 and freed those who had been accused of being smugglers.

Abdourahamane, a local grandee, stood beside the Grand Mosque in Agadez and talked about the migrants. “The people who come here are our brothers and sisters,” he said. “They come. They rest. They leave. They do not bring us problems.” The mosque, built of clay, bears within it the marks of the desert, but it is not transient. Abdourahamane told me that it goes back to the 16th century, long before modern Europe was born. Many of the migrants come here to get their blessings before they buy sunglasses and head across the desert, hoping that they make it through the sands and find their destiny somewhere across the horizon.

By Vijay Prashad

Author Bio: This article was produced by Globetrotter.

Vijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor, and journalist. He is a writing fellow and chief correspondent at Globetrotter. He is an editor of LeftWord Books and the director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. He has written more than 20 books, including The Darker Nations and The Poorer Nations. His latest books are Struggle Makes Us Human: Learning from Movements for Socialism and (with Noam Chomsky) The Withdrawal: Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan, and the Fragility of U.S. Power.

Source: Globetrotter

Widening The ‘We’

04-03-2024 ~ Political polarization—the inability of groups such as political parties, religious sects, and cultural identity groups to cooperate even in basic, essential matters—has been a worry and a threat since American democracy began, and for many centuries before. James Madison called it “faction,” and in The Federalist, No. 10, he wrote, “The friend of popular governments never finds himself so much alarmed for their character and fate as when he contemplates their propensity to this dangerous vice.”

04-03-2024 ~ Political polarization—the inability of groups such as political parties, religious sects, and cultural identity groups to cooperate even in basic, essential matters—has been a worry and a threat since American democracy began, and for many centuries before. James Madison called it “faction,” and in The Federalist, No. 10, he wrote, “The friend of popular governments never finds himself so much alarmed for their character and fate as when he contemplates their propensity to this dangerous vice.”

Madison had good reason to be concerned. Seventy-four years after he wrote this, polarization turned toxic as the United States plunged into a bloody Civil War over slavery that has sent shock waves through American politics ever since. Some of those reverberations—over racial and social justice—have contributed to making the first half of the 21st century one of the most polarized periods in U.S. history, raising fears for the future of democracy and deeper concerns that our society could sink into tribal violence. A 2022 poll found that 28 percent of Americans considered “political extremism or polarization” to be “one of the most important issues facing the country, trailing only ‘inflation or increasing costs’ and ‘crime or gun violence.’”

Polarization is not simple. At the most basic level, it is produced by rigid differences of outlook and opinion that make reaching a consensus on social aims difficult. Every issue appears to crystallize into an insoluble opposition: Black versus white, market efficiency versus social justice, unemployment versus inflation, and social security versus accumulating debt. Polarization turns toxic when discussion, let alone consensus, becomes impossible and violence seems inevitable, ending with the elevation of popular movements into tyrannies and the consignment of opposing groups to prison or the guillotine. This is the outcome many fear is becoming possible today.

Toxic polarization is the product of three factors in individual and social development, all of which can be traced back to the beginnings of human society: malignant bonding, the scarcity mind, and historical and trans-historical trauma. Each factor develops independently, but they reinforce each other to produce a society that is prone to intractable and violent divisions.

Malignant Bonding

Bonding is a fundamental aspect of human culture. We bond in intimate relationships, as families, but also, and less obviously, in the multitude of associations—friendships, working partnerships, institutional and citizenship ties—that form a society. This promotes understanding and cooperation in the interest of building a community that addresses individuals’ and groups’ needs and aspirations. At its best, bonding is built on goodwill: an inclination in favor of empathy, good-faith communication, mutual aid, and an openness to finding common ground that is inclusive and widely beneficial to change.

But bonding can also be malignant, solidifying communities built on resentment, bigotry, and a desire to exclude those who are “different.” The “longing to belong” can easily lead us to think that the only way to be “in” is not to be left out. The result is a narrowing of the “we”—the larger community’s shared identity—as the powerful assert themselves and the fear of being excluded makes some types of identities and associations dangerous. The narrowing of the “we” reduces our ability to discuss urgent common problems such as climate change, social and economic inequality, and the upsurge in mass migration and displacement, let alone permit a consensus on policies to address these issues.

The absence of goodwill marks the difference between constructive and malignant bonding, and hence, between polarization and toxic polarization. When goodwill is present, it is possible to disrupt the perceptions at the root of toxic polarization and malignant bonding and open up space for the consideration of inclusive change. When goodwill is frozen out, this alternate course is almost impossible to perceive. Read more

Rising Talk Of School Closures Fuels Expansion Of The Community Schools Movement

04-03-2024 ~ “Instead of seizing the chance to close schools… communities across the country are pushing their districts to think about schools differently and the possibilities this moment gives us.”

04-03-2024 ~ “Instead of seizing the chance to close schools… communities across the country are pushing their districts to think about schools differently and the possibilities this moment gives us.”

Judging by a rash of news reports beginning in late 2023, communities across the country may be gearing up for a massive wave of school closures in 2024. “A school closure cliff is coming,” warned an article in the Hechinger Report in August 2023. The headline of a January 2024 article in the 74 read, “Exclusive Data: Thousands of Schools at Risk of Closing Due to Enrollment Loss.” Also in January, an article in Education Week with the headline, “Pressure to Close Schools Is Ramping Up. What Districts Need to Know,” highlighted potential or confirmed closures in Boston, Memphis, Tennessee, Wichita, Kansas, Jackson, Mississippi, Missouri, and Indiana.

The standard narrative in these reports is that the COVID-19 pandemic pushed families into online learning in 2020 and emptied school buildings. This was such a massive disruption that parents turned to alternative education options such as charter schools, private schools, microschools, and homeschooling. That transfer of students, along with the drying up of emergency relief funds that the federal government gave to schools to address the impact of the pandemic, have stressed state and local education budgets to the point of having to cut costs, including closing school buildings.

Both education reporters and policy experts tend to frame stories about school closures as “difficult” but “inevitable.” Justifications for closures are steeped in the language of business and economics with words like “efficiency” and “rightsizing” dominating the discourse. District leaders tend to be portrayed as pragmatic realists doing what’s best for children, while efforts to include parents and teachers in decisions over how many schools to close and where are often cast as “placating the adults.”

At the end of the typically torturous process of closing schools almost no one is pleased, especially in low-income Black and brown communities where closures most often occur.

Students, both those whose schools were closed and those in schools receiving an influx of students from the closed schools, are often negatively impacted by closures. And numerous studies about school closures for financial reasons have found that the promised savings from closing school buildings generally never materialize.

Because of the mostly negative results of closing schools, educators and public school advocates that Our Schools recently spoke with want school and policy leaders to rethink why and how they decide to close schools.

Many question the narrative about the need to close schools. They call for district and policy leaders to take steps to ensure families and community members are more involved in closure decisions. They also believe that school district leaders should be more proactive in avoiding school closures by implementing policies and programs that are more likely to attract and hold onto families.

Moreover, school closure skeptics are calling for policy leaders to change their thinking about schools and to regard them as permanent community assets rather than fleeting enterprises that come and go. Their strategy of choice for transitioning to an education system with long-term sustainability is for districts to adopt what’s called the community schools approach.

It’s a big ask, but one that might be perfectly positioned for a moment when policy leaders and government officials are faced with decisions over how to ensure every student has access to a high-quality neighborhood school. Read more

The EU Is Marching Toward An Independent And Integrated Military

John P. Ruehl – Source: Independent Media Institute

04-02-2024 ~ The EU’s evolving common defense network is decades in the making, yet remains hindered by its inability to match NATO and apprehension by some member states.

At the European Defense Agency’s annual conference in November 2023, President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen warned member states from buying too much equipment from abroad and called for a European Defense Union. While the defense union is yet to materialize, the first-ever European Defense Industrial Strategy signed in early March 2024 marked another significant step toward achieving European Union (EU) military autonomy by focusing on improving European weapons manufacturing.

The EU’s collective military spending reached almost $300 billion in 2023, more than China’s official defense budget. Yet its collective weapons stocks remain low, its aircraft, ships, and tanks aren’t ready for combat, and its member states lack logistical and coordination experience. With these shortcomings, debate continues over whether the military policies of EU member states are determined in their capitals, Brussels, or Washington, D.C.

Public support in EU states for a common defense and security policy has nonetheless remained above 70 percent in the 21st century. Washington has maintained a balancing strategy of encouraging dependency among European NATO/EU states, while ensuring they remain capable military allies. But fluctuating attitudes by U.S. administrations toward European defense initiatives have exacerbated uncertainty regarding their autonomy, and integration efforts have continued to evolve since Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

France’s 1951 proposal for a European Defense Community (EDC) among itself, West Germany, Italy, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands found significant support in Washington. Seeking to create a complementary to NATO to collectively face the Soviet Union, U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles threatened an “agonizing reappraisal” during a 1953 NATO summit of Washington’s role in NATO if the EDC failed to materialize.

Despite the rejection of the EDC French parliament, the Western European Union (WEU) military alliance was established in 1954 as a viable alternative. It included the UK and West Germany, paving way for the latter’s entry into NATO in 1955. France’s dissatisfaction with the dominance of British and American interests in NATO saw it reduce its participation and integration in NATO during the 1960s, later emphasizing the WEU for greater European military integration.

However, French attempts to position the WEU as a credible alternative faltered. Even after the end of the Cold War and Soviet collapse, Europe continued to rely heavily on U.S.-led NATO, particularly evident during the 1990s Yugoslav Wars.

Yet U.S. policymakers viewed the establishment of the EU in 1993 as a challenger to NATO and capable of competing in defense contracts. In 1998, France and the historically euroskeptic UK signed the Saint Malo declaration, committing to create a European Security and Defense Policy (ESDP) and envisaging a still-unrealized 60,000 strong European force. The Clinton administration expressed concern about potential discrimination against non-EU states, duplicating the role of NATO, and delinking it from the EU. Undeterred, the EU established the ESDP framework in 1999, and the WEU was transferred to the EU in 2000.

The burgeoning NATO-EU military rivalry was somewhat tempered by efforts to bolster cooperation and coordination, including the 2001 NATO-EU Framework Agreement and 2003 Berlin Plus Agreement. The creation of NATO’s rapid reaction force in 2003 also blunted the EU’s ambitions, while Eastern European states sought NATO assurances, not the EU’s, because of concerns over Russia.

However, 2003 also marked the debut of the Eurofighter Typhoon fighter jet, a joint EU project involving Germany, the UK, Italy, and Spain through the Eurofighter GmbH consortium. Originating in the 1980s, this venture marked a major milestone in European defense collaboration, and today European defense firms such as Airbus, BAE Systems, Leonardo S.p.A., and Dassault, can compete with U.S. weapons exports globally.

Nurturing Europe’s dependency on U.S. power has historically been an effective strategy for Washington to maintain control of the alliance. During the NATO-led intervention in the Libyan Civil War, the Obama administration urged European allies to assume a leading role, but they faced challenges due to limited weapons stocks and coordination. France, which rejoined NATO military command in 2009, was then provided significant U.S. assistance in Africa from 2014, including air-refueling flights and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, aligning with broader U.S. initiatives in Africa. Read more

Thailand Leads Southeast Asia: Parliament Approves Landmark Same-Sex Marriage Bill

03-31-2024 ~ Thailand’s lower house endorses historic same-sex marriage bill, paving the way for southeast Asia’s first marriage equality law amid evolving LGBTQ+ rights landscape.

03-31-2024 ~ Thailand’s lower house endorses historic same-sex marriage bill, paving the way for southeast Asia’s first marriage equality law amid evolving LGBTQ+ rights landscape.

Legislators in Thailand’s lower house of Parliament have decisively endorsed a marriage equality bill, marking a historic step towards becoming the first Southeast Asian nation to legalize equal marriage rights for all people. On March 27, 2024, 400 out of 415 attending lawmakers voted in favor of the bill.

“This is the beginning of equality. It’s not a universal cure for every problem. Still, it’s the first step towards equality,” Danuphorn Punnakanta, an MP and chairman of the lower house’s committee on marriage equality, told Parliament while presenting a draft of the bill.

The bill must undergo approval by the Senate and receive endorsement from the Thai king. Following this endorsement, it would be published in the Royal Gazette and become law after 60 days. If it happens, Thailand will join Taiwan and Nepal as one of the few countries in Asia to legalize same-sex marriage.

The National Assembly has debated different versions of the legislation since December last year. Subsequently, the cabinet of Prime Minister Srettha Thavisin sent the bill to Parliament. Initially, four draft bills on same-sex marriage were proposed by various political parties, which were later consolidated into one. In 2020, the constitutional court upheld the constitutionality of the country’s marriage law, which only recognized heterosexual couples. However, it recommended expanding the law to ensure the rights of other types of couples.

The law, which redefines marriage as a partnership between two individuals rather than solely between a man and a woman, grants LGBTQ+ couples equal rights. These rights include marital tax savings, inheritance entitlements, and the ability to give medical treatment consent for ill partners. Additionally, under the law, married same-sex couples can adopt children.

However, the lower house did not adopt the committee’s suggestion to replace the terms “fathers and mothers” with “parents.” A government survey conducted late last year indicated overwhelming support for the bill, with 96.6 percent of respondents in favor.

The rights to marry and form a family are fundamental rights acknowledged in Article 23 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), a treaty ratified by Thailand. Currently, 37 countries have included same-sex marriage in their national laws. Taiwan set a precedent in 2019 by becoming the first Asian country to recognize same-sex marriage. Meanwhile, Nepal acknowledged a nontraditional marriage in 2023 under an interim order from the Supreme Court, awaiting a final judgment.

In 2015, Thailand enacted the Gender Equality Act to offer legal safeguards against gender-based discrimination, particularly targeting unfair treatment of LGBTQ+ individuals. Nonetheless, the law retains provisions that permit the justification of discrimination against LGBTQ+ individuals on grounds of religion or national security. Furthermore, legal gender recognition remains absent, depriving transgender and non-binary individuals of the ability to officially alter their surname or gender on official records.

Same-Sex Marriage in Asia

In Asia, the legal landscape regarding same-sex marriage is evolving, with only Taiwan and Nepal currently recognizing such unions. Taiwan made history on 24 May 2019, becoming the first country in the region to legalize same-sex marriage nationwide. This milestone followed a landmark ruling by the Constitutional Court and subsequent legislative reforms. Meanwhile, Nepal has been a pioneer in LGBTQ+ rights, with the Supreme Court granting permission for same-sex marriage as early as 2008. This progressive stance was further solidified by the 2015 constitution, which explicitly prohibits discrimination based on sexual orientation.

Despite strides towards equality, Nepal continues to navigate the legal intricacies of recognizing same-sex unions. In a significant move on June 28, 2023, Supreme Court Justice Til Prasad Shrestha directed the government to establish a dedicated register for sexual minorities and nontraditional couples, allowing for their temporary registration. However, a definitive verdict from the Supreme Court on the broader recognition of same-sex marriage is still awaited, underscoring the ongoing legal debate surrounding LGBTQ+ rights in the country.

Against this backdrop, November 2023 marked a historic moment in Nepal’s LGBTQ+ journey. In Dordi Rural Municipality in western Nepal, Maya Gurung, a 35-year-old transgender woman, and Surendra Pandey, a 27-year-old gay man, legally formalized their union.

Meanwhile in India, the journey towards obtaining legal recognition for same-sex relationships has been rife with legal and societal challenges. A significant breakthrough occurred in 2018 when the Supreme Court of India took a groundbreaking step by decriminalizing consensual same-sex relations, marking a pivotal moment of progress for the LGBTQ+ community.

However, in a notable turn of events in 2023, the Supreme Court bench led by Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud unanimously rejected the legalization of same-sex marriage. Moreover, the court voted 3 to 2 against acknowledging civil unions for non-heterosexual couples. This ruling dealt a blow to activists who had campaigned for equal rights within the realm of marriage.

This decision underscored the crucial role of legislative action in shaping the fate of same-sex marriage. The court abstained from interpreting the Special Marriage Act (SMA) 1954 to encompass same-sex unions, emphasizing that such matters lie within the purview of Parliament and state legislatures. Despite this setback, the court reiterated the fluid nature of the institution of marriage and affirmed the equal right of queer individuals to form unions, i.e., to stay as a live-in couple or have a relationship short of marriage.

The SMA is a piece of Indian legislation that allows individuals of different religions, nationalities, castes, or communities to solemnize their marriage through a civil ceremony. It provides a legal framework for interfaith and inter-caste marriages and offers provisions for the registration and validation of such unions.

Meanwhile, other prominent countries in Asia are also grappling with the complexities surrounding same-sex marriage. In China, there is no nationwide recognition of same-sex marriage. In countries such as Cambodia and Japan, partnership certificates are available only in specific cities or prefectures. In contrast, Hong Kong provides spousal visas and benefits to same-sex partners, highlighting stark differences from countries such as Afghanistan, Brunei, Iran, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, where homosexuality can result in the death penalty.

The level of social acceptance towards LGBT individuals varies considerably, with evolving public attitudes and ongoing discussions influencing the trajectory of same-sex marriage rights across the region. Advocacy efforts and legal battles persist as communities strive for equality and acknowledgment in a continent marked by complex social dynamics.

By Pranjal Pandey

Author Bio: This article was produced by Globetrotter.

Pranjal Pandey, a journalist and editor located in Delhi, has edited seven books covering a range of issues available at LeftWord. You can explore his journalistic contributions on NewsClick.in.

Source: Globetrotter

- Page 4 of 4

- previous page

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4