Levende-Doden ~ Summary

‘Living-Dead: African-Surinamese perceptions, practices and rituals surrounding death and mourning’ describes and interprets the death culture of the descendants of African slaves, Creoles and Maroons, in Suriname. The book offers an integrated approach in which a wide range of attitudes comes to the fore, and uncommon (supernatural, bad or tragic) and common (natural, good) death are studied together. In this way, the study presents a comparative and reflexive perspective that reconciles ethnographic detail with middle range theories.

‘Living-Dead: African-Surinamese perceptions, practices and rituals surrounding death and mourning’ describes and interprets the death culture of the descendants of African slaves, Creoles and Maroons, in Suriname. The book offers an integrated approach in which a wide range of attitudes comes to the fore, and uncommon (supernatural, bad or tragic) and common (natural, good) death are studied together. In this way, the study presents a comparative and reflexive perspective that reconciles ethnographic detail with middle range theories.

The book is guided by two leitmotifs. The first concerning the coexistence of tradition and modernity or the phenomenon of multitemporal heterogeneity, arguing that African-Surinamese actors always live, on the one hand, in terms of conflicting demands, desires and expectations associated with voices of authority and, on the other, with the idiosyncratic aspirations of the individual. Processes like creolization, syncretization/anti-syncretization and de-/retraditionalization play a prominent role in this dialectic and, consequently, in the construction of African-Surinamese death culture as well as people’s changing attitudes towards dying, death and mourning.

Despite this dynamic nature, African-Surinamese culture is characterized by an inevitable constant that forms the second leitmotif of this study: the living-dead. Throughout this study it appears that within the African-Surinamese worldview and spiritual-religious orientation, (biological) death does not necessarily mean the end of life. Death rather implies a continuation of life in another form, in which contacts between the living and the deceased (or their spirits) are still possible. The dead are not dead: they are the living-dead who might interfere in people’s lives – as spiritual entities or simply as a lasting remembrance. Living-dead have therefore to be handled with utmost care and respect, while the rituals regarding death, burial and mourning are considered as the most important rites de passage of African-Surinamese culture.

Because of the enormous significance of the living-dead and the subsequent transitional rituals, an important part of this book consists of the description, analysis and interpretation of the ritual process that starts at the deathbed or even before the dying hour. In the conceptualization of death as a process and transition, I draw heavily on Van Gennep’s model of rites of passage, Hertz’s study of liminal rituals as well as his insights into the relationship between corpse, soul and mourners, and several contemporary followers of these founding fathers. In order to grasp all the different ritual stages that surround the process of dying, death and mourning, one first needs an understanding of the sociocultural and religiousspiritual perceptions behind the ritual practices as well as an outline of the social-economic and political context in which people live, die, bury, grief and mourn.

The introductory chapter of this book discusses therefore not only some key concepts and approaches that molded my notion of conducting ethnographic fieldwork on African-Surinamese death culture, but portrays also the precarious situation in which the Surinamese society found itself during my research (1999, 2000). In brief, the country and a large part of its population suffered enormously by a severe economic crisis and a grinding poverty that, because of political and financial-monetary misgovernment, was becoming structural and most in line with Latin-America. At the edge of a new millennium Suriname had deteriorated into one of the worst functioning economies of the region. The process of marginalization hit many if not all my informants in the field, and caused a chasm between a small and privileged group of rich haves (gudusma, elite) and a growing mass of poor have-nots (tye poti). The latter increasingly lacked access to health care, suffered various sanitary inconveniences and subsequent diseases, and saw itself exposed to all kinds of life-threatening conditions, ‘new’ diseases and causes of death. Read more

Levende-Doden ~ Glossarium, Bijlagen I, II & Literatuurlijst

Glossarium – PDF

Bijlage I – Interviews – PDF

Bijlage II – Casussen, situatie-analyses & observaties[i] – PDF

i. Nota bene: het betreft hier volledig uitgewerkte casussen. Veldaantekeningen betreffende allerhande dagelijkse of frequente activiteiten, zoals begraafplaatsbezoek, ‘routinematig’ bijwonen van begrafenissen, mortuariumbezoek, rouwvisite en veel hanging around, zijn niet opgenomen in deze lijst.

Literatuur

Abbenhuis, M.F., 1966 Honderd jaar missiewerk in Suriname door de Redemptoristen, 1866-1966. Paramaribo: [s.n.].

Agerkop, T., 1982 Saramaka Music and Motion. Anales Del Caribe 2: 231-245. Read more

Carole McGranahan & Uzma Z. Rizvi (Eds,) ~ Decolonizing Anthropology

Just about 25 years ago Faye Harrison poignantly asked if “an authentic anthropology can emerge from the critical intellectual traditions and counter-hegemonic struggles of Third World peoples? Can a genuine study of humankind arise from dialogues, debates, and reconciliation amongst various non-Western and Western intellectuals — both those with formal credentials and those with other socially meaningful and appreciated qualifications?” (1991:1). In launching this series, we acknowledge the key role that Black anthropologists have played in thinking through how and why to decolonize anthropology, from the 1987 Association of Black Anthropologists’ roundtable at the AAAs that preceded the 1991 volume on Decolonizing Anthropology edited by Faye Harrison, to the World Anthropologies Network, to Jafari Sinclaire Allen and Ryan Cecil Jobson’s essay out this very month in Current Anthropology on“The Decolonizing Generation: (Race and) Theory in Anthropology since the Eighties.”

Just about 25 years ago Faye Harrison poignantly asked if “an authentic anthropology can emerge from the critical intellectual traditions and counter-hegemonic struggles of Third World peoples? Can a genuine study of humankind arise from dialogues, debates, and reconciliation amongst various non-Western and Western intellectuals — both those with formal credentials and those with other socially meaningful and appreciated qualifications?” (1991:1). In launching this series, we acknowledge the key role that Black anthropologists have played in thinking through how and why to decolonize anthropology, from the 1987 Association of Black Anthropologists’ roundtable at the AAAs that preceded the 1991 volume on Decolonizing Anthropology edited by Faye Harrison, to the World Anthropologies Network, to Jafari Sinclaire Allen and Ryan Cecil Jobson’s essay out this very month in Current Anthropology on“The Decolonizing Generation: (Race and) Theory in Anthropology since the Eighties.”

Read more: http://savageminds.org/series/decolonizing-anthropology/

Fountain Hughes ~ Voices From The Days Of Slavery

Fountain Hughes (age 101 at the time of this interview) recalls his younger years when he and his family lived as slaves as well as some good advice on how to spend money.

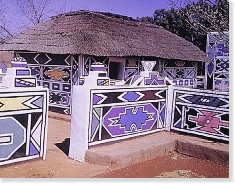

The Ndebele Nation

12-05-2015 ~ With an Introduction by Milton Keynes

The Ndebele of Zimbabwe, who today constitute about twenty percent of the population of the country, have a very rich and heroic history. It is partly this rich history that constitutes a resource that reinforces their memories and sense of a particularistic identity and distinctive nation within a predominantly Shona speaking country. It is also partly later developments ranging from the colonial violence of 1893-4 and 1896-7 (Imfazo 1 and Imfazo 2); Ndebele evictions from their land under the direction of the Rhodesian colonial settler state; recurring droughts in Matabeleland; ethnic forms taken by Zimbabwean nationalism; urban events happening around the city of Bulawayo; the state-orchestrated and ethnicised violence of the 1980s targeting the Ndebele community, which became known as Gukurahundi; and other factors like perceptions and realities of frustrated economic development in Matabeleland together with ever-present threats of repetition of Gukurahundi-style violence—that have contributed to the shaping and re-shaping of Ndebele identity within Zimbabwe.

The Ndebele history is traced from the Ndwandwe of Zwide and the Zulu of Shaka. The story of how the Ndebele ended up in Zimbabwe is explained in terms of the impact of the Mfecane—a nineteenth century revolution marked by the collapse of the earlier political formations of Mthethwa, Ndwandwe, and Ngwane kingdoms replaced by new ones of the Zulu under Shaka, the Sotho under Moshweshwe, and others built out of Mfecane refugees and asylum seekers. The revolution was also characterized by violence and migration that saw some Nguni and Sotho communities burst asunder and fragmenting into fleeing groups such as the Ndebele under Mzilikazi Khumalo, the Kololo under Sebetwane, the Shangaans under Soshangane, the Ngoni under Zwangendaba, and the Swazi under Queen Nyamazana. Out of these migrations emerged new political formations like the Ndebele state, that eventually inscribed itself by a combination of coercion and persuasion in the southwestern part of the Zimbabwean plateau in 1839-1840. The migration and eventual settlement of the Ndebele in Zimbabwe is also part of the historical drama that became intertwined with another dramatic event of the migration of the Boers from Cape Colony into the interior in what is generally referred to as the Great Trek, that began in 1835. It was military clashes with the Boers that forced Mzilikazi and his followers to migrate across the Limpopo River into Zimbabwe. Read more

Margot Leegwater ~ Sharing Scarcity: Land Access And Social Relations In Southeast Rwanda

Land is a crucial yet scarce resource in Rwanda, where about 90% of the population is engaged in subsistence farming, and access to land is increasingly becoming a source of conflict. This study examines the effects of land-access and land-tenure policies on local community relations, including ethnicity, and land conflicts in post-conflict rural Rwanda. Social relations have been characterized by (ethnic) tensions, mistrust, grief and frustration since the end of the 1990-1994 civil war and the 1994 genocide. Focusing on southeastern Rwanda, the study describes the negative consequences on social and inter-ethnic relations of a land-sharing agreement that was imposed on Tutsi returnees and the Hutu population in 1996-1997 and the villagization policy that was introduced at the same time. More recent land reforms, such as land registration and crop specialization, appear to have negatively affected land tenure and food security and have aggravated land conflicts. In addition, programmes and policies that the population have to comply with are leading to widespread poverty among peasants and aggravating communal tensions. Violence has historically often been linked to land, and the current growing resentment and fear surrounding these land-related policies and the ever-increasing land conflicts could jeopardize Rwanda’s recovery and stability.

Land is a crucial yet scarce resource in Rwanda, where about 90% of the population is engaged in subsistence farming, and access to land is increasingly becoming a source of conflict. This study examines the effects of land-access and land-tenure policies on local community relations, including ethnicity, and land conflicts in post-conflict rural Rwanda. Social relations have been characterized by (ethnic) tensions, mistrust, grief and frustration since the end of the 1990-1994 civil war and the 1994 genocide. Focusing on southeastern Rwanda, the study describes the negative consequences on social and inter-ethnic relations of a land-sharing agreement that was imposed on Tutsi returnees and the Hutu population in 1996-1997 and the villagization policy that was introduced at the same time. More recent land reforms, such as land registration and crop specialization, appear to have negatively affected land tenure and food security and have aggravated land conflicts. In addition, programmes and policies that the population have to comply with are leading to widespread poverty among peasants and aggravating communal tensions. Violence has historically often been linked to land, and the current growing resentment and fear surrounding these land-related policies and the ever-increasing land conflicts could jeopardize Rwanda’s recovery and stability.

Full text book: http://www.ascleiden.nl/news/sharing-scarcity