Jan Briffaerts – When Congo Wants To Go To School. Educational Realities In A Colonial Context

Rozenberg Quarterly will publish on paper and online:

Jan Briffaerts – When Congo wants to go to school. Educational realities in a colonial context. An investigation into educational practices in primary education in the Belgian Congo (1925-1960) – Pb – 420 pag. – € 39,50 – ISBN 978 90 3610 144 8 – 2014

The education system in the Congo was widely considered to be one of the best in colonial Africa, in particular because of its broad reach among the Congolese youth. At independence however, the wake-up call was brutal as soon it became clear that the colonial educational system had neglected to form an educated class of people able to cope with administrating one of Africa’s biggest and economically most important countries. To be able to understand the mechanisms and effects of missionary education it is most enlightening to go back to the classroom and investigate the everyday reality of school. What did missionary education do exactly, how did it work, what did it teach, and how did it relate to its subjects, the children of the Congo?

This study gives clear insights into the everyday realities of colonial education. It is the result of historical research into educational practices and realities in catholic missionary schools in the Tshuapa region, located in the south of the Congolese province of Equateur. It is based on a rich array of historical source material, ranging from missionary archives and mission periodicals through to contemporary literature and interviews with missionnaries and former pupils who experienced colonial education themselves. The title, “When Congo wants to go to school… ” refers to one of many articles published in Belgian mission periodicals on the subject of the education and civilisation work carried out by missionaries in the Belgian colony.

The complete book now online:

Introduction & A Few Preliminary Remarks

Educational Organisation In The Belgian Congo (1908-1958)

The Missionaries And The Belgian Congo: Preparation, Ideas And Conceptions Of The Missionaries

Catholic Missions In The Tshuapa Region

Part II – Realities

The Educational Climate

Educational Comfort

The Subject Matter

Educational Practices

Part III – Acti Cesa

The Short Term: Reactions

The Long Term: Memories

As Justification And Conclusion

Appendices & Bibliography

When Congo Wants To Go To School – Introduction & A Few Preliminary Remarks

The research project that formed the foundation for this study grew from a few existing lines of research. On the one hand it relates to research on the so-called Belgian civilisation project in the Congo, on the other to research into the micro-history of education in Belgium. Both my promoter and I have some experience in research into colonial education. Marc Depaepe’s work on the colonial phenomenon grew out of a representative, personal connection to it. As with many Flemish people, the colonial past was a part of his family history. The letters from his great aunt, Sister Maria Adonia Depaepe, a missionary in the Congo between 1909 and 1961, which he later published, are a testimony to this.[1] Her personal documents were published as part of a project on the history of education, more specifically the missionary action of the Belgians in the former colony. The result was a general study at a macro level based on the theory of historical education, focussing in on the educational policy and institutional development of colonial education.[2] At about the time this book was published I was writing an extended paper in the framework of the “Historische kritiek” (tr. Historical criticism) lectures in the history department at the Vrije Universiteit Brussels. The subject of my paper was the “school struggle” in the nineteen fifties in the Belgian Congo. This paper really related to a part of political history and the political players behind colonial education, particularly in Belgium and to a limited extent the Belgian Congo.[3] Some years later the content of the paper was presented at a colloquium on 50 years of the school pact (2nd and 3rd December 1998, V.U.B.) and published in the resulting conference notes.[4] Read more

The research project that formed the foundation for this study grew from a few existing lines of research. On the one hand it relates to research on the so-called Belgian civilisation project in the Congo, on the other to research into the micro-history of education in Belgium. Both my promoter and I have some experience in research into colonial education. Marc Depaepe’s work on the colonial phenomenon grew out of a representative, personal connection to it. As with many Flemish people, the colonial past was a part of his family history. The letters from his great aunt, Sister Maria Adonia Depaepe, a missionary in the Congo between 1909 and 1961, which he later published, are a testimony to this.[1] Her personal documents were published as part of a project on the history of education, more specifically the missionary action of the Belgians in the former colony. The result was a general study at a macro level based on the theory of historical education, focussing in on the educational policy and institutional development of colonial education.[2] At about the time this book was published I was writing an extended paper in the framework of the “Historische kritiek” (tr. Historical criticism) lectures in the history department at the Vrije Universiteit Brussels. The subject of my paper was the “school struggle” in the nineteen fifties in the Belgian Congo. This paper really related to a part of political history and the political players behind colonial education, particularly in Belgium and to a limited extent the Belgian Congo.[3] Some years later the content of the paper was presented at a colloquium on 50 years of the school pact (2nd and 3rd December 1998, V.U.B.) and published in the resulting conference notes.[4] Read more

Ben Petersen ~ A Story About The Garifuna

A rich Central American culture is fast disappearing in the wake of immigration and integration. This film chronicles the challenges and struggles of the Garifuna people to preserve their identity. The story serves as a microcosmic example of the loss of time-honored customs in a world that is increasingly becoming one homogenous international culture.

A Ben Petersen Film

A Brigham Young University Communications Department Production

Produced, directed, and edited by Ben Petersen

Additional footage provided by: Jared Johnson, Dale Green and Jorge Zuniga.

Funding Provided by the BYU Office of Research and Creative Activities, BYU Communications Department and the B&A Trust Fund.

Music by Michael Bahnmiller. “Ba-ba” by Aziatic.

Kyrgyzstan ~ A Country Remarkably Unknown

Kyrgyzstan is a remarkably unknown country to most world citizens. Since its conception in the 1920s, outside observers have usually treated it as a backwater of the impenetrable Soviet Union.

Kyrgyzstan is a remarkably unknown country to most world citizens. Since its conception in the 1920s, outside observers have usually treated it as a backwater of the impenetrable Soviet Union.

There was little interest and even less opportunity to gather information on this particular Soviet republic. But even within the Soviet Union, Kyrgyzstan was relatively unknown. It is as likely to meet a person from Russia or the Ukraine who has never heard of Kyrgyzstan as someone from the Netherlands or the USA. As one of my informants who has a Kyrgyz father and a Russian mother said:

I was raised in Kazan in Russia and went to school when the Soviet Union still existed. The kids in school did not understand that I was Kyrgyz. I sometimes explained, but they still thought I was Tatar, or from the Caucasus. We were taught some facts and figures about Kyrgyzstan in school, but that was it.

Kyrgyzstan briefly became world news in March 2005, when it was the third in a row of velvet revolutions among former Soviet Union countries. President Akayev, who had been the president since 1990 (one year before Kyrgyzstan’s independence) was ousted, to be replaced by opposition leaders who had until recently taken part in Akayev’s government.

A few years before that, Kyrgyzstan had become a focus of interest in the War on Terrorism, because of its majority Muslim population and its vicinity to Afghanistan. The country opened its main airport Manas for the Coalition Forces, who all stationed troops there.

The lack of a solid general base of background information gives the study of Kyrgyzstan a special dimension. Researchers and audience do not share images of the country that are based on a large number of impressions from different sources. Thus, every morsel of new information becomes disproportionally important in the creation of new images, and may be taken out of perspective. It also means that the researcher does not have an extensive body of knowledge to fall back on. Questions that are raised can often not be answered, as there is no corpus of data and general consensus. This can give the researcher a sense of walking on quick sand, but it also keeps the researcher, and hopefully her audience as well, focused and unable to take anything for granted.

In this paper I will give an overview of images of Kyrgyzstan as it is portrayed in journalist reports, travel guides, and works of social scientists. This will provide the reader unfamiliar with Kyrgyzstan with a framework of background information that cannot be presupposed.

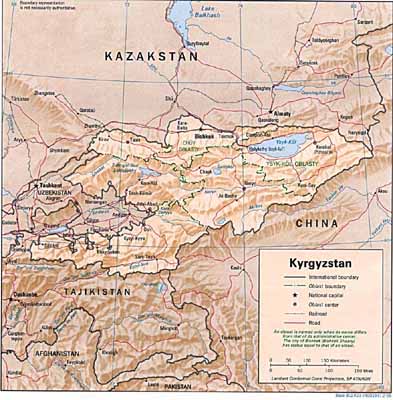

Kyrgyzstan Located

Kyrgyzstan, a country of 198,500 square km, is about the size of Great Britain. Its population of 5 million is considerably less than that of the UK, however, because of the mountains that cover the larger part of the country. Kyrgyzstan’s impressive mountain ranges, known as the Tien Shan, Ala Too and Alay ranges, are extensions of the Himalayas. Ninety per cent of Kyrgyzstan’s territory is above 1,500 metres and forty-one per cent is above 3,000 metres. Perpetual snow covers about a third of the country’s surface. Large amounts of water, in the form of mountain lakes and wild rivers, are a consequence of this landscape.

Kyrgyzstan is landlocked and bordered by four countries, three of which are former Soviet Union republics. Kazakhstan lies to the North, Uzbekistan to the West and Tajikistan to the South. The Eastern border is shared with China, or more precisely: with the Chinese province Xinjiang, home of many Turkic and Muslim peoples.

Administratively, Kyrgyzstan is divided into seven provinces (oblus, from Russian oblast) and two cities (shaar). The two cities are Osh city and the country’s capital Bishkek. Bishkek was known as Frunze during Soviet times, named after Red Army hero Mikhael Frunze. In 1991, four months before independence, the city was renamed Bishkek (Prior, 1994:42).

Kyrgyzstan is commonly divided in the North and South. The South consist of three provinces: Jalal-Abad, Osh and Batken. Batken was separated from Osh after the invasion of Islamic guerrillas in August 1999. The North consists of the Chüy, Talas, Ïssïkköl and Narïn provinces. Looking at the map, it is clear that ‘North’ and ‘South’ are not so much geographical indications, as Ïssïkköl and Narïn are at the same latitude as Jalal-Abad. A mountain ridge with very few passages, however, separates the North from the South, making them far apart in people’s experience. If one travels from Osh to Narïn, for instance, one usually takes a triangle route through Bishkek. There is a road that traverses the mountain ridge that separates them, but snow often renders it impassable. Until 1962, there was not even a road between Osh and Bishkek (then: Frunze), the railway that connected the two cities ran by way of Tashkent.

The term ‘Kyrgyzstan’ is a choice out of a number of names for the country. Presently, the official name in the Kyrgyz language is Kïrgïz Respublikasï. In English, it is ‘the Kyrgyz Republic’, after the ‘h’ in Kyrghyz was dropped in 1999. One year before independence, shortly after Akayev’s appointment as president, the Republic of Kyrgyzstan became the official name for the republic after it announced its sovereignty (Rashid, 1994:147). In May 1993, this was changed to the Kyrghyz Republic. Another often-heard name for the country is Kirgizia, which is based on Russian, who substituted the ï (usually transliterated as y) by an i to fit Russian grammatical rules. Popular in the country itself is the word ‘Kyrgyzstan’. This term is not new, but was already in use in the early days of the Soviet Union. In this dissertation, I will join with popular habit and refer to the country as Kyrgyzstan. Read more

University Of Pennsylvania Museum Of Archaeology And Anthropology Films

![]() In its 120-year history, the University of Pennsylvania Museum has collected nearly one million objects, many obtained directly through its own field excavations or anthropological research. Three gallery floors feature materials from ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, the Bible Lands, Mesoamerica, Asia and the ancient Mediterranean World, as well as artifacts from native peoples of the Americas, Africa and Polynesia. This collection on the Internet Archive represents a portion of the motion picture film collection housed at the Museum. Please note that cataloging and identification of subjects will progress over a period of time

In its 120-year history, the University of Pennsylvania Museum has collected nearly one million objects, many obtained directly through its own field excavations or anthropological research. Three gallery floors feature materials from ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, the Bible Lands, Mesoamerica, Asia and the ancient Mediterranean World, as well as artifacts from native peoples of the Americas, Africa and Polynesia. This collection on the Internet Archive represents a portion of the motion picture film collection housed at the Museum. Please note that cataloging and identification of subjects will progress over a period of time

The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology holds copyright to these films. Please contact the Penn Museum Archives at 215-898-8304 or at photos@pennmuseum.org to request permission to reproduce this footage.

Enjoy: https://archive.org/details/UPMAA_films

Savage Minds | Notes and Queries in Anthropology

Savage Minds is a group blog devoted to ‘doing anthropology in public’ — providing well-written relevant discussion of sociocultural anthropology that everyone will find accessible. Our authors range from graduate students to tenured professors to anthropologists working outside the academy.

Savage Minds is a group blog devoted to ‘doing anthropology in public’ — providing well-written relevant discussion of sociocultural anthropology that everyone will find accessible. Our authors range from graduate students to tenured professors to anthropologists working outside the academy.

Savage Minds was founded in 2005. In 2006 Nature ranked Savage Minds 17th out of the 50 top science blogs across all scientific disciplines. In 2010, American Anthropologist called Savage Minds “the central online site of the North American anthropological community” whose “value is found in the quality of the posts by the site’s central contributors, a cadre of bright, engaged, young anthropology professors.” In 2014 we hope to have our blog deposited into the National Anthropological Archives at the Smithsonian.

The title of our blog comes from French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss’s book The Savage Mind, published in 1966. The original title of the book in French, Pensée Sauvage, was meant to be a pun, since it could mean both ‘wild thought’ or ‘wild pansies,’ and he put pansies on the cover of the book, just to make sure readers got the pun. Lévi-Strauss was unhappy with the English title of his book, which he thought ought to have been “Pansies for Thought” (a reference to a speech by Ophelia in Hamlet). We liked the phrase “savage minds” because it captured the intellectual and unruly nature of academic blogging. As a result, the pansy has become our mascot as well.

Go to: http://savageminds.org/