When Congo Wants To Go To School – Catholic Missions in the Tshuapa Region

To give a more coherent picture of the development of education in the region studied, it is necessary to start with a brief explanation of the development of the church hierarchy in the region and the way in which this was concretized by the religious orders that would become responsible for education. This subject will be covered in this chapter in two parts. The first part handles the evolution of the church hierarchy in a strict sense and the delineation of what would eventually become the mission area of the MSC. The presence and missionary work of the Trappists in the area will be discussed first. Chronologically, this history only begins once this congregation had decided to leave the Congo, but it is useful to consider a number of events from the preceding period in order to understand the activities of the MSC properly. The identity and presence of the other religious orders in the mission region and their involvement in education will then be outlined. Finally, the second part will describe a quantitative development of the schools in the vicariate on the basis of a number of statistical data. This will enable us to give the direct context of the reality in the classroom that will be considered in more detail in the second part.

1. The missionary presence

1.1. How the missionaries of the Sacred Heart obtained a vicariate in the Congo

In the church hierarchy, the area around Mbandaka and the Tshuapa was originally a part of the apostolic vicariate of the Belgian Congo, founded in 1888. It was put under the leadership of the congregation of Scheut, which was the first Belgian congregation to send missionaries to the Congo.[i] Naturally, in subsequent years the evangelisation of the Congo Free State as a whole expanded further, the number of congregations active in the Congo greatly increased and the administrative church structure was repeatedly adapted.

1.1.1. The Trappists of Westmalle on the Equator[ii]

Chronologically, the protestant Livingstone Inland Mission was the first to establish itself at the mouth of the Ruki in the Congo River. That was in Wangata in 1883. In the same year and in the same place, Stanley, together with the officers Coquilhat and Vangele,[iii] founded the state post Equateurville, which was clearly separated from the mission that had been set up earlier.[iv] In 1895 the monopoly of the Protestants in the region ended with the arrival of the first Trappists.[v] The original intention of this contemplative order was the establishment of a closed monastic community in Bamanya, about eight kilometres from Equateurville, “following the example of the monks in the middle ages.“[vi]

Thanks to its strategic situation at the confluence of two important rivers, Equateurville, renamed Coquilhatville from 1892, developed rather quickly to become a so-called circonscription urbaine.[vii]Nevertheless, it would take until 1902 before the Trappists, at the request of the colonial administration, set up the parish of Boloko wa Nsimba, still “forty minutes away from the state post of Coquilhatville“.[viii] Meanwhile, the developing state post was abandoned by the Protestants. The post of Wangata was moved to Bolenge (about ten kilometres outside Coquilhatville) and the Livingstone Inland Mission was replaced by the Disciples of Christ Congo Mission.[ix] Even before the First World War, the Trappists built a church in Coquilhatville and provided evangelical teaching there. Even so, their activities in this urban environment remained very limited. Marchal says in this regard: “The trappists, simple people from the rural Kempen region, had an aversion to great centres.”[x] In the twenties the General Chapter in Rome decided that the Trappists of Westmalle had to leave the Congo and return to their monastic way of life, which was considered irreconcilable with the missionary work in the Congo.[xi] In 1926 the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart of Issoudun (hereafter referred to by their official abbreviation “MSC”) took over their area. Read more

When Congo Wants To Go To School – Part II – Realities

In the following chapters I will try to reconstruct the educational reality in the schools of the MSC based primarily on the written sources available. More specifically, this relates to the reconstruction of classroom life and the educational relationship between missionaries and pupils. The closer one gets to the so-called ‘micro level’, the more apparent it becomes that it is almost impossible to make a true reconstruction in the sense of a true representation, “wie es eigentlich gewesen ist”, of the educational relationship between missionaries and Congolese. Naturally, the source material available is important here and defines the boundaries within which the research can be carried out.

In the following chapters I will try to reconstruct the educational reality in the schools of the MSC based primarily on the written sources available. More specifically, this relates to the reconstruction of classroom life and the educational relationship between missionaries and pupils. The closer one gets to the so-called ‘micro level’, the more apparent it becomes that it is almost impossible to make a true reconstruction in the sense of a true representation, “wie es eigentlich gewesen ist”, of the educational relationship between missionaries and Congolese. Naturally, the source material available is important here and defines the boundaries within which the research can be carried out.

A second important matter is that the teaching was not given by the missionaries in the first place, but by the Congolese. This is not unique to the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart, it is more generally true for the entire colony. From the beginning an appeal was made to native assistance, to carry out the huge quantity of work caused by the evangelisation project. A decision was already made in 1907 by the bishops in the Congo to establish a central teacher-training course for each church province. The reason for this was of course the unbalance between the personnel available and the population to be reached. The fact that evangelisation was much more important to the missionaries than the educational activity meant that it was “sufficient” initially to train the Congolese as catechists and that it was not necessary in the strict sense to train teachers. This was also emphasised in those first plans: the candidates for training had to be young (maximum 12 years old) and it was explicitly stated that the intention was not to train educationalists but catechists as assistants to the missionaries.[i] According to Antoine Dibalu there were 11 central teacher-training colleges in 1922, of which those closest to the Equator province were situated in Nouvel Anvers (North of Coquilhatstad) and in Tumba (by Lake Tumba, South of Coquilhatstad).[ii] However, it is likely that not everybody who became teaching assistant had actually attended a teacher training college. That was certainly true in the mission region of the MSC.[iii] One example of this can be found in the Annals from 1929: “On Tuesday there is a school inspection. Notwithstanding all kinds of unfavourable circumstances satisfactory results have been achieved. The head teaching assistant, Georges Lobombe, although he has not had any professional training, was given an honorary mention in the inspector’s report.”[iv][v]

From a statistical summary from 1934 it is apparent that a little over 120 “white” religious workers were working in the vicariate Coquilhatstad, together with 90 teachers and 357 catechists. It was also stated that there were another eighty pupils or so at the teacher training college at that time. Consequently, an attempt was made to have trained teachers but that was clearly not always the case. Moreover, the same was true for the missionaries themselves. They had, barring a few exceptions, no educational training. The missionaries’ role was often limited to supervising the teaching assistants and to giving religious education. One of the many testimonies in this regard was given in the Annals by Sister Godfrieda, a Sister of the Sacred Heart, who worked in the newly established mission post in Bolima from 1934: “Here you will find Sr. M. Godfrieda, who tries to keep order with two black helpers among the three hundred and fifty rascals and to drum the first concepts of discipline, prayer and the catechism into them and to teach them some letters and arithmetic.”[vi] Relatively speaking, more people with educational training could be found among the sisters than at the MSC. The MSC were not a teaching order by nature. Consequently, it should not be surprising that when a large school had to be established in a central place, as in Coquilhatville, the Brothers of the Christian Schools were appealed to, being traditionally considered an educational congregation. Read more

When Congo Wants To Go To School – The Educational Climate

Moral foundation and worldview

The clear moralising impact of the curricular was indicated in the previous chapter. This moralising also seems a very good reflection of the climate in which missionary intervention and education took place. This fact was very clearly brought to the fore in the mission periodical of the MSC. It was repeatedly pointed out that, as far as the missionaries were concerned, Christianisation was the most important concern. This remained the same throughout the colonial period, although it levelled off towards the end and was concealed by other, more worldly-oriented educational objectives. In 1926, one of the MSC pioneers, Father Es, wrote about the settlement in Boende: “We are situated on a small plateau in the middle of the tropical forest, far from the state outpost and every native village, so as to reduce the influence of the heathens and the whites to a minimum. The purer the Christian atmosphere, the better the Christians.“[i] The same Father Es wrote about the lessons themselves: “Those classes, as dull and monotonous as they are – we know from our own experience of taking them as children – do not bore them. They constantly ask for more. And together with these reading, writing, drawing and maths lessons, the Christian spirit penetrates their heart drop-by-drop. Everything on the mission breathes this exalted spirit which will only make them more human. Our goal is after all not only to form developed Negroes, but also developed Christians.“[ii]

The statements made in the Annals sound disarming to contemporary ears, sometimes even shockingly naïve. For this reason they are a good indicator of the state of affairs. The opinions in the metropolis were not so different or more ‘elevated’ that they needed to mince words. In the end of year edition of the Annals in 1931 the following could be read: “Why mission expansion? Because we need money, our beautiful mission territory around the equator forest, which is six times bigger than Belgium, needs to be provided with more priests, more Brothers, more churches, more schools. Why mission expansion? Because otherwise the Protestants will take advantage! Because otherwise the Protestants, with all their gold, will stack the best part of the harvest in their own stores. (…) Why expansion? Because the need for souls is so great that the waves engulf the ship of the church.”[iii] That there was a need for souls was obvious to all missionaries and to the home front. That something needed to be done about it was at least as obvious to the missionaries. And the competitive element towards other religious convictions naturally became a part of this.[iv]

Petrus Vertenten, who was an abbot and known as a very cultivated man,[v] wrote in 1930, without mincing his words, that: “Our principal work is the salvation of souls, and it is going well, very well. Here at the station we regularly have about 500 people who come to the catechetic lessons. They stay here a year and then we have to chase them away to make room for others.“[vi] Later he also wrote that Congolese children were interested in the mission station: “To obtain wisdom and knowledge, that is an investment which stays, knowledge to read and write and so many other things and especially to become a Christian.“[vii] This statement reveals much more about the intentions of the author than of the children. Other missionaries also stated the same motivation: “It remains noble work, making decent Christians of the black heathen children. That is for a large part the task of the mission Sisters.“[viii] About the heathens in the bush, in the fifties he wrote: “Through education and prayer exercises they have more contact with God and they hope to become good Christians.”[ix]

This was not only propaganda language, reserved for publications intended to promote the missionary cause to the general public. Although some things were worded in attractive language, these sorts of statements are representative of what the missionaries thought. The ‘pure Christian culture’ element played a big role, which, for example, finds great expression in the writings of Gustaaf Hulstaert. When the influence of the proposed curriculum reform of 1938 filtered through into the region, he was thoroughly annoyed. In a letter to the governor general he lamented the fact that the primary schools of the Brothers of the Christian Schools in Coquilhatville all operated in preparation of secondary education. He was clearly and thoroughly opposed to the proposed ‘two track system’, under which education had to function both as preparatory and as final education:[x] “Through the application of your new directives, all the young men from Coq and its surroundings will be isolated because of the broken lives they would lead. Of course, on the one hand you intend an education without any connection with indigenous life which fatally produces semi-intellectuals and classless people; while on the other hand you advocate sending back to the mass of indigenous population, the greater majority of these pupils for whom the education will be completely inappropriate.” Read more

When Congo Wants To Go To School – Educational Comfort

This chapter is primarily concerned with the development of the ‘educational comfort’ in the region of the MSC. This term must be further explained. ‘Educational comfort’ was used by Marc Depaepe to describe a larger body of elements that, taken together, contribute to the ‘comfort’ of education and of being taught. In the first instance I will be concerned here with the material organisation of the educational activity. As was set out in chapter 3, the missionaries built up a network of schools. This building must also be taken in the literal sense of the word. The material aspect of education is often the best documented, in the form of archives and other sources. The schools at the larger mission posts are mainly those referred to in the different articles and reports. This implies that the general picture is unavoidably a little distorted, even here, because the mission posts were much better equipped than the little schools in the bush.[i] ‘Educational comfort’ is naturally not only the material equipment, it is also everything that goes with or is connected with the existence of a building in which education is undertaken. By this I do not mean that I am primarily concerned with everything that is used in teaching in the colonial classroom, although that does contribute to the full picture. ‘Comfort’ includes the integration of the schools in the society as much as in the mission posts and also the upkeep, the material aspect of living. Or, to put it another way, the ‘material management’ of education. Other aspects of the reality of classes, such as discipline and timetabling, will only be considered later.

Appearance of the classroom

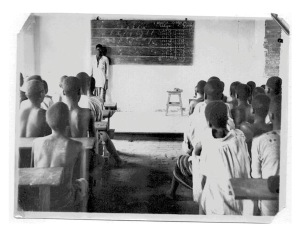

Before moving to information that comes from the written sources, I wish to present on a few photographs of ‘classroom life’. Such pictures are rather scarce, certainly within the boundaries of the MSC mission region. They are naturally interesting because they visually present a particular aspect of reality. It is true that this relates more to the material environment than the behaviour, considering that the ‘life’ shown is posed in many cases. Everything naturally depends on what one allows the photographs to tell. The descriptions that follow here give a vague idea of what it was like then, although they raise as many questions as they answer.

The photographs in image 15 show a school in Nsona Mbata (in the neighbourhood of Matadi) in 1922. The pupils are in a building, in any case they are more or less closed off from the environment and they have some protection against the vicissitudes of the climate. It is difficult to say whether this is a room that is specifically meant for education. What is noticeable in the photograph is that there is certainly more than one teacher operating in the same room. The children are evidently divided into groups. At first sight there are four groups of children, on closer inspection five can be distinguished (on the right-hand photograph they can all be seen, three at the back, two at the front). The first teacher stands at the blackboard and teaches something about a text written on the board. It is not clear what the topic is. In an enlargement of the photograph it seems to be about syllables, which could indicate that this was a reading lesson. The second teacher is sitting at a table as are the pupils who are clearly forming his class. There is a pile of papers on his table (exercise books or textbooks?) and there is also a clock (an alarm) and there is something lying there that looks like coins. The second teacher also has a blackboard that (perhaps because of the photographer) is pushed completely to the side. In total there must be between fifty and seventy children sitting together in this room. The group at the back, who are sitting on school desks, clearly have slates and slate pens, which they are using. With the groups at the front these instruments cannot be seen and a few pupils seem to be holding something (an exercise book?).

The photograph in image 16 is a picture of a class in the MSC missionary region from around 1950. The material environment in which the lesson is given is very sober but shows more specific characteristics that are commonly associated with the concept of ‘school’ in comparison to the previous photographs. The teacher – who poses stiffly – stands on a platform before the class. On the large blackboard that is fixed to the wall there are a number of letters on the left, which indicate a writing lesson. A number of arithmetic sums can be seen on the right. The school desks are narrow and more than two pupils sit at them at a time. As far as can be seen, the room being used as a classroom is built in stone and the walls are more or less plastered. On the floor there is also some sort of stone or paving. The school is clearly built from some sort of durable material. Still, this is supposed to be a rural school, going by the clothing of the pupils and above all the assistant. He is wearing a pagne, which would not have been permitted at the mission posts.[ii] Finally, the photographs in figure 17 are taken at a central mission school. The classrooms have glass windows. On the photograph on the left a sort of overhang can be seen behind the frame, probably a barza, which makes one suppose that the classroom is part of a larger school building.[iii] The school desks have a better finish, the pupils sit in pairs. They are not wearing uniforms but it is clear that there is a sort of dress code. On the left there is a map of the Belgian Congo on the wall together with a few other undoubtedly didactical pictures. On the right, pictures are also on display and a cupboard with didactical material (probably measuring vessels). These classes undoubtedly look the most ‘European’. Read more

When Congo Wants To Go To School – The Subject Matter

In the previous chapters, what was actually happening during lessons became dimly visible here and there. In this chapter this will be examined more closely. Learning in a class situation can be approached in many different ways. I assume in any case that a combination of various points of view is needed to achieve a picture of ‘reality’. What was taught? This can be deduced from the content of curricula tested by the commentary in inspection reports. It can also be partially deduced from the subject matter in the textbooks used. How was this taught? This is actually a question of the pedagogical principles the missionaries adhered to: did they talk about this? Did these principles even exist?

What was in the curriculum?

The curricula for subsidised missionary education have already been discussed in chapter two. By and large the period in question can be divided as follows, using the applicable curriculum guides: the period from 1929 to 1949, under the first curriculum (the Brochure Jaune), from 1949 to just after half-way through the 1950s, under the second (and third) curriculum and the second half of the 1950s, in which métropolisation was imposed (and, in principle, the Belgian syllabus should have been implemented). Apart from the fact that the transition between the different periods, especially between the second and third, is not very strictly defined, the first curriculum was noticeably enforced for the majority of the colonial period (taking the previously discussed proposal of 1938 into account). It did not seem worthwhile to analyse the changes in lesson content between the curricula of 1929 and 1948 in detail. After all it is almost certain that there is no general and direct concordance between what was required in the curriculum guides and what was actually taught. The curriculum guides only gave minimal norms, general guidelines and guiding principles. Obviously, it did not include the detailed contents of lessons. The third and final reason was that the curriculum was fragmented in the guide of 1948 through the introduction of the distinction between the normal and ‘selected’ second grade. This made an orderly comparison more difficult. The evolution of the two curricula in the area of subject content will only be touched upon very briefly.

However, it did seem worthwhile to make a summary comparison of colonial and Belgian curricula, especially to try to counter a certain representation. Otherwise it might be assumed too easily that the education in Belgian Congo was no more than a kind of occupational therapy. The researcher and the reader are faced here with a very subtle balancing exercise. On the one hand, the intention is to discover the reality, or at least to try: the ‘how’ and ‘what’ of school reality in the past. On the other hand, it is necessary to articulate what almost everyone will be thinking automatically when reading a story of the period: namely that ‘it wasn’t the way it is now’ and that the attitudes of a number of protagonists, namely the missionaries, were fairly ‘old-fashioned’, even ‘primitive’ or ‘backward’.

Of course such an opinion seems suspiciously similar to remarks made by the missionaries themselves about the Congolese (which partly causes them) but this does not mean they should not be mentioned. Nor should they necessarily be attacked with moral judgements but, on the other hand, they should be interpreted. In the first instance it is of course only human to distance oneself in one way or another from events that happened in other places at other times. We must, of course, avoid falling into an a-historical position but the reaction itself is not an historical aberration, in the sense of ‘very wrong at the time’. After all, in the same way the ideas of the missionaries are not to be considered as thoughts that ‘should not really have been thought’ and should have given rise to moral indignation. The foundations of the stance assumed in the colonial context are, after all, to be found in structures, positions and reactions in the home context of the colonisers. This can also be shown clearly in the context of the curricula. Read more

When Congo Wants To Go To School – Educational Practices

In this chapter the focus shifts slightly to didactic and educational practices, insofar as these can be known. This is used in the meaning of every day interaction between missionaries, moniteurs (teaching assistants) and pupils. The inspection reports give some insight here into what really happened, although in most cases from a distance. Although the reports and letters from inspectors may be said to be perfect examples of the normative, this does not mean that they make it possible to see clearly what practices were criticised and for which practices alternatives were offered. Two contrasts that were discussed earlier appear again and ‘mark’ distinctions between them. The first is the distinction between the centre and periphery, which, in this context coincides with the dichotomy mission school – rural school. In the previous chapters it was obvious that the material situation was very different depending on whether a school was situated at the central mission post school or a bush school. The second contrast between the two types of teachers, missionaries or moniteurs corresponds largely with the mission school – rural school situation. These distinctions are, in fact, situated almost entirely within the context of the central mission school, considering that, almost by definition, no missionaries taught in rural schools.

In this chapter the focus shifts slightly to didactic and educational practices, insofar as these can be known. This is used in the meaning of every day interaction between missionaries, moniteurs (teaching assistants) and pupils. The inspection reports give some insight here into what really happened, although in most cases from a distance. Although the reports and letters from inspectors may be said to be perfect examples of the normative, this does not mean that they make it possible to see clearly what practices were criticised and for which practices alternatives were offered. Two contrasts that were discussed earlier appear again and ‘mark’ distinctions between them. The first is the distinction between the centre and periphery, which, in this context coincides with the dichotomy mission school – rural school. In the previous chapters it was obvious that the material situation was very different depending on whether a school was situated at the central mission post school or a bush school. The second contrast between the two types of teachers, missionaries or moniteurs corresponds largely with the mission school – rural school situation. These distinctions are, in fact, situated almost entirely within the context of the central mission school, considering that, almost by definition, no missionaries taught in rural schools.

However, they do not correspond completely. Ideally, it should be possible to identify three different situations within the context of (Catholic) missionary education: A first situation in which pupils received education without any, or only sporadic, intervention from missionaries. This is what was found in rural schools; a second situation, in which a moniteur gave lessons in a central mission post, near to missionaries but not in their permanent presence; and a third situation in which the missionaries exercised permanent control over what happened in the class or gave lessons themselves. This third situation was, as should already be clear, quite unusual (except in the initial phase of a mission post). In a number of cases one subject was given systematically by missionaries. Usually that was religious education. In other cases one class, and usually the highest one, was entrusted to the care of a missionary. This occurred mostly from necessity because no native teacher could be found who was suitable for the job. In girls education there were, relatively speaking, more female religious who actually taught themselves. This must be explained by the fact that female education was way less developed because of the social context in which Congolese girls functioned and because of the position of the female religious workers themselves.

The organisation of this chapter is not, in fact, along these lines. The available sources were, after all, almost exclusively produced by the missionaries themselves. It also seems to me to be difficult to deal in an even-handed manner with situations in which the missionary staff were absent and to give them, quantitatively speaking, just as much space as the others. For this reason another approach was chosen. It starts from general observations or questions (“topics”). This is probably less structured but at the same time also ‘more honest’ towards the reality studied in the sense that it has been decided beforehand to start from one particular aspect, to collect information about this and to discuss it, but without causing the reality to ‘stop’ at a particular moment. In any event this approach is easier to grasp because in this way we avoid telling a too compartmentalised story, whereby for each of the three proposed hypotheses the same topics would need to be dealt with again and again.

Discipline

1.1. The school rules: theory…

In principle every school had to have school rules: “In every class there hangs a set of rules for the Colony: there is a lot on it, 20 numbers composed by the Father Director of the Colony himself. Get up … attend Holy mass… Work… school… eat… go to sleep… and so forth…“[i] The scope of the rules probably differed strongly according to the place and the congregation that was active there. A very interesting example for the study of classroom reality is the rather comprehensive rulebook of the Brothers of the Christian Schools, created for the Groupe Scolaire in Coquilhatville.[ii] In theory, the Brothers had been given responsibility for the pupils during school time but in practice their reach went further. The rulebook contained a mixture of instructions that was directed at the moniteurs and the pupils. It constitutes a very normative source, to the extent that we can expect it to effectively reflect reality for a large part. The book begins with a list of provisions that applied to the teaching staff. It applied to their behaviour and also to their tasks with respect to the pupils. Among these, a lot of attention is paid to religiously inspired themes. After a few indications for the maître chrétien himself (enough prayer, be punctual, make sure that the timetable is respected), there follows the first chapter “éducation chrétienne“. Reciting the correct number of prayers a day, the use of a rosary, going to mass and confession at set times: it was the task of the teaching staff to make sure that the pupils certainly did these. “Enseignement” was only mentioned in the second section. Here, a number of items were discussed in connection with the teaching method, from which not very much can be deduced about the reality. The teacher must follow the curriculum and make an effort to pass perfect knowledge on to the pupils: “He shall carefully prepare his lessons and give methodical and graduated education. He shall apply himself to cultivating the intelligence of his pupils as well as their memory and language.” Read more