Recht en Opleiding

Aanvankelijk was het Molengraaff Instituut gevestigd aan de Nieuwegracht 60 van 1958 tot 1991, vervolgens aan de Nobelstraat 2 van 1991 tot 2012, zie foto. Nu is het instituut gevestigd op Janskerkhof 12.

Inleiding

Universiteiten geven aan een stad status en aanzien. Zij zijn van groot belang voor de economische, culturele en intellectuele ontwikkeling van een stedelijke gemeenschap. De universiteit is altijd zichtbaar aanwezig in en rondom een stad. Dit geldt ook voor Utrecht, met als prachtig middelpunt het Academiegebouw op het Domplein en de studentensociëteit ‘PHRM’ op het Janskerkhof. De Utrechtse universiteit kent vanaf de stichting in 1636 een rechtenfaculteit. Het recht is een bepalende factor in de Europese cultuur en samenleving, vandaag meer dan ooit. Daarom is het gerechtvaardigd dat Corjo Jansen bijzondere aandacht besteedt aan de ontwikkeling van de Utrechtse juridische faculteit gedurende de afgelopen vier eeuwen.

Het was 07.00 uur in de ochtend, 17 juni 1634. De zon brak langzaam door, toen de hoogwaardigheids bekleders van de stad Utrecht zich vol trots verzamelden op het stadhuis, in de panden Lichtenberg en Hasenberg, gelegen aan de Oudegracht, nog steeds de plek van het huidige stadhuis en het beginpunt van onze wandeling. Bij hen hadden zich de reeds in toga gehulde hoogleraren gevoegd die waren benoemd aan de fonkelnieuwe Illustre School van de stad. Iedereen maakte zich op voor twee lange dagen. De plechtigheden ter gelegenheid van de opening zouden over een uur, enkele honderden meters verderop, een aanvang nemen in het kapittelhuis bij het Domplein, thans het Academiegebouw van de Utrechtse universiteit, eenvoudig te bereiken via een korte tocht over de huidige Vismarkt, daarna linksaf onder de Domtoren door.

Een opleiding aan de ‘illustere school’ was te plaatsen tussen die aan het gymnasium en de academie. De oprichting van een dergelijke onderwijsinstelling was voor veel stadsbesturen met pretenties de eerste stap op weg naar een volwaardige universiteit. Hetzelfde gold voor de Utrechtse vroede vaderen. Zij hadden daarvoor de steun nodig van de Staten van het gewest Utrecht. De stichting van een universiteit of school was staatsrechtelijk gezien voorbehouden aan de soeverein, de persoon of de instelling die was belast met het oppergezag over de onderdanen. Na de afzwering van Philips II als landsheer in 1581 werd de officiële leer in de Republiek dat de soevereiniteit bij de afzonderlijke Staten van elke provincie berustte. Het recht om een universiteit te stichten kwam, evenals bijvoorbeeld het recht om een vredesverdrag te sluiten en de bevoegdheid om wetten te maken, aan de Staten toe. Het Utrechtse stadsbestuur wist dat het daarom met hen moest onderhandelen om zijn School tot de status van universiteit te verheffen. De steun van de Utrechtse Staten was echter niet eenvoudig te krijgen, omdat de concurrentie tussen de steden binnen de provincie groot was. Het was (en is) aantrekkelijk voor een stad om een universiteit binnen de stadspoorten te hebben. Zij fungeert vaak als een van de motoren van de plaatselijke economie. Amersfoort gunde bijvoorbeeld in het Stichtse Utrecht het licht niet in de ogen en omgekeerd was dat ook het geval. Utrecht heeft uiteindelijk, zoals we weten, de strijd gewonnen.

Het Utrechtse stadsbestuur liet bij de opening van de Illustre School op 17 juni 1634 weinig na om indruk te maken op de leden van de Utrechtse Staten. Om acht uur vertrokken in grote grandeur de burgemeesters, de schout, de overige notabelen en de hoogleraren naar de voormalige kapittelzaal in het kapittelhuis bij het Domplein. De zaal was in tweeën gedeeld. Het grootste vertrek was bestemd voor de colleges van de theologische en de juridische faculteit en kreeg de aanduiding auditorium theologicum. Het was de bedoeling van het stadsbestuur dat vier van de vijf nieuw benoemde hoogleraren gedurende die twee dagen hun ambt zouden aanvaarden. Het publiek bestond volledig uit genodigden: de Statenleden, de raadsheren uit het Utrechtse gerechtshof (de hoogste rechterlijke instelling in de provincie), de predikanten en de Utrechtse notabelen. De twee dagen in de harde banken van het auditorium gingen heen met het luisteren naar de in het Latijn gestelde redes en muzikale intermezzo’s van onder meer de stadstrompetters en een a-cappellakoor. Aan het einde van de tweede dag was er een uitgelezen banket, in calvinistische traditie niet al te copieus. Read more

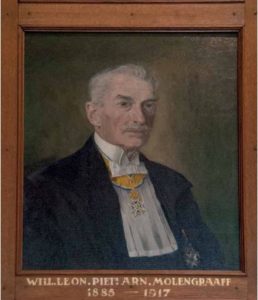

Uitgelicht ~ Willem Molengraaff (1858-1931)

Nijmegen was Molengraaffs geboorteplaats. Na het doorlopen van de Latijnsche School begon hij in 1875 aan de rechtenstudie in Leiden. Hij rondde die in 1880 af met een proefschrift, getiteld Internationale Averij-Grosse Regeling. Zoals zo veel jonge juristen viel hij voor de bekoring van de hoofdstedelijke advocatuur. Dit nobele beroep verhinderde hem niet stevig aan de weg te timmeren. Samen met zijn confrères Hendrik Lodewijk Drucker (1857-1917) en Samuel Katz (1845-1890) richtte hij in 1882 het Rechtsgeleerd Magazijn op. Het tijdschrift had tot doel de ramen open te zetten in het muffe huis van de Nederlandse rechtsgeleerdheid. Molengraaff, Drucker en Katz stonden een actieve rol van de staat in het maatschappelijk leven voor. Het recht moest in overeenstemming worden gebracht met de sociale behoeften van de samenleving. Moraal en fatsoen zagen zij als richtsnoer voor de wetgever en de rechter.

Molengraaffs faam in juridisch Nederland groeide snel. In 1883 preadviseerde hij – nog geen 25 – voor de Nederlands(ch)e Juristen-Vereniging (NJV) over de noodzakelijkheid en wenselijkheid van het onderscheid tussen het burgerlijk recht en het handelsrecht. De slotsom van zijn uitvoerige historisch rechtsvergelijkende tournee was dat er geen sprake kon zijn van een handelsrecht, dat gelijkwaardig was aan het burgerlijk recht. Het handelsrecht was aan het burgerlijk recht ondergeschikt. Het regelde een aantal voor de handel belangrijke onderwerpen, die in beginsel door de dogmatiek van het burgerlijk recht werden beheerst. Na het preadvies van Molengraaff is de overbodigheid van een afzonderlijk handelsrecht nauwelijks meer betwijfeld. Het heeft toch nog een halve eeuw geduurd, voordat het onderscheid tussen burgerlijk recht en handelsrecht bij wet van 2 juli 1934 (Stb. nr. 347) werd opgeheven.

Een week na de succesvolle verdediging van het preadvies op de NJV-vergadering van 31 augustus 1883 trad Molengraaff als adjunct-secretaris toe tot de in 1879 ingestelde Staatscommissie tot herziening van het Wetboek van Koophandel. Molengraaff kreeg de taak toebedeeld ‘het faillietenrecht te behandelen’. Hij toog aan het werk. Zeven maanden later (!), in november 1884, had hij het ontwerp voor een nieuwe faillissementswet af. In 1885 werd hij secretaris van de Staatscommissie.

Op ongeveer hetzelfde moment, op 24 januari 1885, volgde Molengraaffs benoeming tot hoogleraar handelsrecht en burgerlijke rechtsvordering in Utrecht. Hij ging wonen op de Maliebaan, nr. 43b. Zijn oratie droeg de titel: Het verkeersrecht in wetgeving en wetenschap. Het thema van zijn beschouwing was het noodlottige dualisme tussen het recht uit de wetboeken en het feitelijke, in de maatschappij levende recht, met name op het gebied van het handelsrecht.

Molengraaff ontpopte zich snel tot een van de gezaghebbendste beoefenaren van het handels- én burgerlijk recht in Nederland. Het artikel, waarmee hij zijn naam definitief vestigde, lag op het snijvlak van beide rechtsgebieden: “De ‘oneerlijke concurrentie’ voor het Forum van den Nederlandschen Rechter”. Het verscheen in het Rechtsgeleerd Magazijn van 1887 (p. 373-435). In Molengraaffs tijd van opkomende industriële activiteit was de repressie van de oneerlijke mededinging een actueel thema. Hij suggereerde een later befaamd geworden criterium om dit euvel te bestrijden:

Hij die anders handelt dan in het maatschappelijk verkeer den eenen mensch tegenover den ander betaamt, anders dan men met het oog op zijne medeburgers behoort te handelen, is verplicht de schade te vergoeden, die derden daardoor lijden.

De Hoge Raad heeft Molengraaffs criterium overgenomen in zijn beroemde arrest Lindenbaum/Cohen van 31 januari 1919 (NJ 1919, p. 161).

Vanaf 1889 verscheen zijn omvangrijke Leid(d)raad bij de beoefening van het Nederlandsche Handelsrecht. Het boek domineerde na verschijning meer dan een halve eeuw dit rechtsgebied. Molengraafff schreef een baanbrekend NJV-preadvies op het gebied van het verzekeringsrecht. Daarnaast werkte hij gestaag door aan de voltooiing van de nieuwe Faillissementswet. Het wetsontwerp werd uiteindelijk op 30 september 1893 (Stb. nr. 140) wet. Zij trad op 1 september 1896 in werking. Molengraaff liet onmiddellijk daarna een handboek over de wet verschijnen: De Faillissementswet verklaard (1896).

De werkkracht van Molengraaff ging die van een normaal mens ver te boven. Naast zijn universitaire werk aanvaardde hij allerlei functies in het bedrijfsleven. Hij werd commissaris bij een aantal bedrijven (waaronder De Nederlandsche Bank). Daarnaast ontplooide hij zich politiek. Molengraaff werd in 1897 voorzitter van de Liberale Unie, het verband van de progressieve liberalen. Hij was in 1901 een van de oprichters van de Vrijzinnig-Democratische Bond (VDB) en korte tijd eerste voorzitter. Van 1900 tot 1918 was hij lid van de Provinciale Staten van Utrecht voor de VDB. Hij ijverde voor de invoering van het algemeen kiesrecht. Dit achtte hij noodzakelijk voor de verwezenlijking van sociale wetgeving in Nederland. Molengraaff stond bekend als een voorvechter van vrouwenrechten. Hij was lid van het Comité tot Verbetering van den Maatschappelijken en den Rechtstoestand der Vrouw.

Aan de vooravond van de 20e eeuw was Molengraaff optimistisch gestemd over de vooruitgang en de voorspoed in de tijden die kwamen. Hij had visioenen van het ontstaan van een wereldrecht, dat hij verbond met de eenwording van de mensheid. De nieuwe eeuw bracht hem in 1902 het rectoraat van de universiteit. Als wetgever zette hij zich in 1905 aan het ontwerp van een nieuwe zeewet. Het ontwerp kwam in 1907 af, maar verdween in een bureaula van het Ministerie van Justitie.

Molengraaffs afscheid als hoogleraar kwam voor de buitenwacht onverwacht. Hij nam in 1917 ontslag. De belangrijkste reden hield vermoedelijk verband met het feit dat het huis aan de Maliestaat 1A, dat hij vanaf 1891 bewoonde, hem deed herinneren aan zijn vrouw, die op 28 oktober 1915 was overleden. Daarnaast was hij diep teleurgesteld over het onvermogen van de Nederlandse wetgever. Hij sprak op 8 juni 1917 in zijn afscheidsrede, ‘Een Terugblik’, bitter over de hopeloze, onherstelbare veroudering van de Nederlandse wetboeken, in het bijzonder van het Wetboek van Koophandel.

In april 1917 kreeg Molengraaff een aanstelling als commissaris-adviseur bij de Rotterdamse Bank Vereniging. Deze betrekking liet hem voldoende ruimte voor het werk aan nieuwe wetgeving. Hij was de motor achter de oprichting van de Vereeniging Handelsrecht. Haar doel was “het verkrijgen van eene handelswetgeving, welke aan de eischen der tegenwoordige samenleving voldoet”. Molengraaff werd in 1919 benoemd tot lid van de Staatscommissie Burgerlijke Wetgeving en voorzitter van de subcommissie Handelswetgeving. Hij nam onmiddellijk het politiek verweesde zeerecht ter hand. Dankzij zijn optreden werd het ontwerp in 1924 eindelijk wet. In 1927 verscheen het eerste gedeelte van zijn Kort Begrip van het Nieuwe Nederlandsche Zeerecht. Molengraaff heeft zich daarnaast met andere handelsrechtelijke wetgeving beziggehouden, zoals het recht met betrekking tot de koopmansboeken, de makelaardij en het wisselrecht.

Molengraaff was in 1925 naar Den Haag verhuisd. De nabijheid van de wetgever joeg hem op. In de lente van 1931 werd hij ziek. Molengraaff overleed op 7 juli in zijn woonplaats Den Haag. Twee dagen later werd hij begraven op de Tweede Algemene Begraafplaats te Utrecht.

The University of Chicago Press ~ The History Of Cartography

The first volume of the History of Cartography was published in 1987 and the three books that constitute Volume Two appeared over the following eleven years. In 1987 the worldwide web did not exist, and since 1998 book publishing has gone through a revolution in the production and dissemination of work. Although the large format and high quality image reproduction of the printed books (see right column) are still well-suited to the requirements for the publishing of maps, the online availability of material is a boon to scholars and map enthusiasts.

The first volume of the History of Cartography was published in 1987 and the three books that constitute Volume Two appeared over the following eleven years. In 1987 the worldwide web did not exist, and since 1998 book publishing has gone through a revolution in the production and dissemination of work. Although the large format and high quality image reproduction of the printed books (see right column) are still well-suited to the requirements for the publishing of maps, the online availability of material is a boon to scholars and map enthusiasts.

On this site the University of Chicago Press is pleased to present the first three volumes of the History of Cartography in PDF format. Navigate to the PDFs from the left column. Each chapter of each book is a single PDF. The search box on the left allows searching across the content of all the PDFs that make up the first six books.

“An important scholarly enterprise, the History of Cartography … is the most ambitious overview of map making ever undertaken …. People come to know the world the way they come to map it—through their perceptions of how its elements are connected and of how they should move among them. This is precisely what the series is attempting by situating the map at the heart of cultural life and revealing its relationship to society, science, and religion…. It is trying to define a new set of relationships between maps and the physical world that involve more than geometric correspondence. It is in essence a new map of human attempts to chart the world.”—Edward Rothstein, New York Times

“It is permitted to few scholars both to extend the boundaries of their field of study and to redefine it as a discipline. Yet that is precisely what The History as a whole is doing.”—Paul Wheatley, Imago Mundi

“A major scholarly publishing achievement.… We will learn much not only about maps, but about how and why and with what consequences civilizations have apprehended, expanded, and utilized the potential of maps.”—Josef W. Konvitz, Isis

Go to: http://www.press.uchicago.edu/books/HOC/index.html

Allison Meier ~ The Revolution Has Been Digitized: Explore The Oldest Archive Of Radical Posters

The oldest public collection of radical history completed a digital archive of over 2,000 posters. The Joseph A. Labadie Collection at the University of Michigan Library announced this month that its posters on anarchism, civil liberties, feminism, labor, and other political movements are online for the first time.

“It’s not enough for us to preserve the artifact if people cannot see it,” Julie Herrada, Labadie Collection curator, told Hyperallergic. “Posters are a difficult format because they are fragile and can only withstand so much physical handling, so providing access to these materials while keeping them safe is a complicated process, or it was, until the technology and resources became more readily available to us.”

Read more: http://hyperallergic.com/the-revolution

Political Capitalism, Overseas Trade And Ethnic Diversity

The aim of this paper is to remind modern researchers studying modern, post-Soeharto Indonesia of the research on the history of political capitalism in Asia, including the Indonesian Archipelago done by the Dutch scholar Van Leur. While preparing his well known thesis on the Asian Trade system, he concluded that the Indonesian island group has a bipartite geopolitical structure. This structure consists of a maritime zone of sea routes and coastal urban centres dominated by local and interregional political capitalism, and a peripheral part that stands partly on its own and is in part connected to the first zone. The question he asked was why the Asian type of political trade capitalism had been able to survive for such a long time and had even had been continued by the V.O.C., while in Europe this form of capitalism had long disappeared.

The aim of this paper is to remind modern researchers studying modern, post-Soeharto Indonesia of the research on the history of political capitalism in Asia, including the Indonesian Archipelago done by the Dutch scholar Van Leur. While preparing his well known thesis on the Asian Trade system, he concluded that the Indonesian island group has a bipartite geopolitical structure. This structure consists of a maritime zone of sea routes and coastal urban centres dominated by local and interregional political capitalism, and a peripheral part that stands partly on its own and is in part connected to the first zone. The question he asked was why the Asian type of political trade capitalism had been able to survive for such a long time and had even had been continued by the V.O.C., while in Europe this form of capitalism had long disappeared.

Today these questions once again become interesting as we become progressively aware that, on both the national and the regional level, the Soeharto regime that fell in 1998 was fuelled by a type of political capitalism that came close to what had existed during pre-colonial and early colonial times. And thus the question of the continuity of political capitalism returns to the agenda of modern Asia research.

In the introduction I pointed out that Indonesia’s recent ethnic tensions occurred especially in the coastal cities and coastal areas where Indonesia’s strategic resources are located, and not to any great degree in the interiors of the major islands. In the course of Indonesia’s long history, many ethnic groups have evidently settled in and around the coastal cities, where they live together. This geographical curiosity has its roots in Indonesia’s past as an international emporium and trade port in the overseas trade between India en China, as well as at certain times between Asia and Europe. This trade needed ports of call [i] under the control and protection of local rulers. These rulers allowed foreigners [ii] that contributed to the settlement’s trade to settle in their own wards with their own heads and courts. These wards had a certain measure of diplomatic immunity, turning the ports of call into places with an international population. In this context, foreign businessmen and traders became the driving force behind maritime Asia’s coastal economy. The geographical position of the urban settlements in the archipelago and their mixed populations has not fundamentally changed in the past two thousand years, as is evident from maps 1 through 2.

The question that arises from this historical continuity is whether the underlying political and economic systems have remained unchanged as well. The answer is partly yes and partly not. Partly yes, because, as will become clear in this chapter, the central organizing factor behind the distribution of coastal cities and ethnic communities has been political capitalism, both then and now[iii]. Partly not, because the modern form of political capitalism in Asia, to wit the nationalistic side of the modern nation-state, subjects everything within its borders to its authority and mistrusts foreign businesses and capital because of their excessive power in the world-markets and their danger to the domestic market. Read more

On Islamic Historiography

By Islamic Historiography I mean written material concerning the events of the early period of Islam written by Muslim historians. This material is essential for any major research on Islam but has been continuously discredited by predominantly Western scholars. Therefore, before the study of these texts, an outline of their characteristics and a short discussion about the criticisms of these texts and their authors is indispensable.

By Islamic Historiography I mean written material concerning the events of the early period of Islam written by Muslim historians. This material is essential for any major research on Islam but has been continuously discredited by predominantly Western scholars. Therefore, before the study of these texts, an outline of their characteristics and a short discussion about the criticisms of these texts and their authors is indispensable.

Among the problems proclaimed in the criticisms are: the gap between the historical events and their recording, the fact that early historical compilations have not survived and have been paraphrased or summarized in later digests, the problem of the oral origin of many reports, the task of the historian, the incompatibility of non-Islamic sources, forged reports, political influences on historiography, the purpose of historiography and the originality of the historian.

In this paper the criticisms concerning the Islamic historiography and the answers of the some historians to these criticisms will be surveyed.

The origin, the terminology and the form of the early Islamic historiography

According to Robinson, Arabs produced very little written material before Islam and relied instead on orality.[1]

It seems logical to conclude that the enormous volume of written work which was produced after Islam[2] must be ascribed primarily to the emphasis in various Qur´ānic verses on writing and the stories in this book about the previous peoples and prophets, which encouraged the Muslims to narrate, and reflect and investigate about the origins of those narrations, examples are, the next two verses:

…By the pen and what they write with it…. (Qur’ān 68:1)

Relate these allegorical stories (to the people) perhaps they might think. (Qur’ān 7:176).3

The second important impetus seems to have been the traditions of the Prophet of Islam which were to be preserved for the future generations. Islamic Tradition informs us that the Prophet of Islam discouraged his followers, in the initial stages of his mission, to write about him in order to prevent any confusion between his sayings and the Qur´ān.[4]

However the reports about the alteration of this attitude in a later stadium encouraged the biographers to write Sīra or biographical collections at the end of the first and beginning of the second Islamic century. The campaigns of the Prophet (Maġāzī) and the conquests (Futūḫ) [5] were the other historical works, produced in the period between the first works and the later great compilations.

The collections with the modern name for history, Ta’riḥ, appeared in the 2nd/9th century.[6]

Their source material consisted of Aḥbār which according to Rosenthal means both information and the events and corresponds to history in the sense of story, anecdote (ḫekāyat). Later, when the term was used together with āthār, it became synonymous to hadīth.[7]

The other sources were the above mentioned Sīra, Maġāzī and Futūḫ works, the books of aḥbāriyyūn and genealogical works and oral accounts.[8]

Thus, the first historical works, as the ordered record of the events of the past, began as a mixture of the above mentioned genres. This is the same multi-faceted character that Robinson says history used to have:

“…coming via Latin from the Greek historia, generally meant ´inquiry´; it earlier described a variety of genres, including geography, folklore and ethnography, in addition to what we would commonly understand to be history.”[9]

And the way Rosenthal defines history:

History in the narrow sense.., should be defined as the literary description of any sustained human activity either of groups or individuals which is reflected in, or has influence upon the development of a given group or individual….for the modern mind, the general concept of history may, in theory, be extended to include all animate or inanimate matters. [10]

While he also mentions that:

Muslim historiography includes those works which Muslims, at a given moment of their literary history, considered historical works and which, at the same time, contain a reasonable amount of material which can be classified ashistorical according to our definition of history, as given above. [11]

Thus, history is made up of many elements which together have certain meaning for certain people. This is by no means the denial of general definitions of or theories about history, rather, the emphasis is on the meaning of a certain concept, object or idea in a specific context.

Not only the combination of aḥbār and āthār became synonymous to ḫadīth, but also the form of historical narratives took the form of ḫadīth. According to Dūrī two perspectives existed among the early compilers: the ḫadīth perspective and the tribal perspective. Very soon, the first perspective prevailed which explains why the Islamic historiography has maintained the form of ḫadīth, thus, beginning with an isnād or chain of transmitters, continued by the report (ḥabar).[12]

The problems concerning the Islamic historiography

Islamic history books and Muslim historians have been the subject of both praise and critique. There are problems concerning the historical texts and those concerning the narrators both historians and their transmitters.

One problem ascribed to Islamic historiography is the fact that there is a gap between the time of the events of the early period of Islam and their historiography. Is this gap so long that it can in fact disqualify the whole historiography? It seems that this gap was not considered to be very important when the Western scholars first came into contact with the Islamic sources of the second and third century of Islamic era.[13] Perhaps this was caused by their earlier experiences with other historiographies. The later recording of the events in Islam had its precedents in other historiographies. For example, according to Robinson: The gap between event and record in early Islam is relatively narrow compared with our source material for the ancient Israelites, which usually dates from several centuries after the facts they purport to relate.[14]

Thus the problem of late compilation does not seem to be restricted to Islamic historiography. Read more