What Will Be The Long-Term Development Of The Population Of The German Reich After The First World War? – Introduction and Abstract

General Introduction

The 1920’s and 1930’s are among the most interesting periods in the history of modelling and forecasting. The continuous decline of Western birth rates in the inter-war period set alarm bells ringing. Concerns about the future size and growth of the populations of these nations were heightened by long-term extrapolations of time series, and by population projections and population forecasts. Concerns turned to acute anxiety after it became to appear that the leading Western European nations would not replace their populations. The imminent population decrease threatened to diminish the relative power of what were called in those days the ‘civilized’ nations and ultimaltely to result in ‘race suicide’ (the extinction of populations).

In some countries statisticians, demographers, or economists developed population projection methodology in order to free current debates on the population issue from emotional, subjective argument. In the two leading Fascist countries – but in other countries as well – population numbers were seen as the key to economic, political and military strenght. Read more

Wie wird sich die Bevölkerung des Deutschen Reiches langfristig nach dem Erstem Weltkrieg entwickeln?

Die ersten amtlichen Bevölkerungsvorausberechnungen in den 1920er Jahren.

Problemstellung

Nach dem Ende des Ersten Weltkriegs rückten die demografischen Veränderungen in den Kriegs- und Nachkriegsjahren in das Zentrum der öffentlichen Debatten. Gegenstand statistischer Analysen bildeten die Geburtenausfälle in den Jahren 1914 bis 1919, die Übersterblichkeit der männlichen Bevölkerung und die Entstehung des Frauenüberschusses, die den Altersaufbau der Reichsbevölkerung nach dem Weltkrieg prägten. Hinzu kamen die Bevölkerungsverluste, die aus der territorialen Neugliederung des Deutschen Reichs in Folge der Umsetzung des Friedensvertrages von Versailles entstanden.1 Das Statistische Reichsamt stellte sich zur Aufgabe, die Verwerfungen in der Alters- und Geschlechtsstruktur als auch die bereits vor dem Weltkrieg eintretenden Veränderungen im Geburtenverhalten zu untersuchen und deren langfristige Auswirkungen auf die Bevölkerungsdynamik zu berechnen. Binnen vier Jahren erstellte das Statistische Reichsamt zwei demografische Vorausberechnungen über die künftige Bevölkerungsentwicklung und -struktur für das Territorium des Deutschen Reiches nach 19192 (Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, 316, 1926 und Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, 401, II, 1930). Die Grundlage für diese ersten zwei amtlichen Vorausberechnungen boten die Ergebnisse der Volkszählungen der Jahre 1910, 1919 und 1925.

Es wurden weitere statistische Erhebungen und Ergebnisse zur natürlichen Bevölkerungsbewegung im Deutschen Reichsterritorium nach dem Erstem Weltkrieg hinzugenommen (Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, 276, 1922; Statistik des Deutschen Reiches, 316, 1926; Statistik des Deutschen Reiches, Sonderhefte zu Wirtschaft + Statistik, 5, 1929, Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, 360, 1930, Statistik des Deutschen Reiches, 401, I +II, 1930).

In der ersten 1926 erschienenen Vorausberechnung wurde die Entwicklung der Bevölkerungsdynamik und -struktur für einen Zeitraum von 50 Jahren (1925 bis 1975) und in der zweiten, 1930 erschienen, für einen Zeitraum von 75 Jahren (1930 bis 2000) und darüber hinaus erstellt.3 Nahe zeitgleich hier zu erarbeitete der Bevölkerungsstatistiker Friedrich Burgdörfer (1890-1967) eine weitere demografische Vorausberechnung.4 Read more

Terra Firma: Ashore in the Bay of Strangers

Friday, 25 August 1995 – “Bosun – topside!” The Captain’s command over the intercom aroused me from a deep sleep. Henri, jumping from his cot, rushed out to film the action on deck. Soon the muffled rattling of the anchor chain reverberated throughout the ship: we were dropping anchor. Slowly, I got up. Fleetingly, ever so fleetingly, a wave of revulsion suffused my body, and I tried not to think about what was outside: a fog-shrouded, ice-cold sea and a huge, empty island. I glanced at my watch: 7:15 a.m. Through the porthole I could see a calm sea, light blue under a low, grey sky. If this was Ivanov Bay, the grave search party would go ashore. If it wasn’t, only the Captain might know where on earth we may be. I got dressed and hurried outside. In the light, drizzly mist that engulfed the ship, Jerzy and Bas were siphoning gasoline into lemonade bottles from a big, rusty fuel barrel on the foredeck, using a rubber hose. Inside, the breakfast table had been set, but there was no time to eat. The landing of the grave-searchers was busily being prepared, as Boyarsky was threatening that the sea might soon get rough again. Only George, with aristocratic unconcern, sat sipping a cup of tea in the otherwise empty mess room. The corridors teemed with foot traffic. The hum of electric motors resonated through the steel vessel as the deck crane deposited a huge stack of wooden beams and planks from the hold into the landing craft. For protection against bears, the Ivanov Bay group would be constructing a hut for their stay. On deck, the atmosphere was frenzied and tension was palpable, with good-byes adding to the din of cargo handling.

Friday, 25 August 1995 – “Bosun – topside!” The Captain’s command over the intercom aroused me from a deep sleep. Henri, jumping from his cot, rushed out to film the action on deck. Soon the muffled rattling of the anchor chain reverberated throughout the ship: we were dropping anchor. Slowly, I got up. Fleetingly, ever so fleetingly, a wave of revulsion suffused my body, and I tried not to think about what was outside: a fog-shrouded, ice-cold sea and a huge, empty island. I glanced at my watch: 7:15 a.m. Through the porthole I could see a calm sea, light blue under a low, grey sky. If this was Ivanov Bay, the grave search party would go ashore. If it wasn’t, only the Captain might know where on earth we may be. I got dressed and hurried outside. In the light, drizzly mist that engulfed the ship, Jerzy and Bas were siphoning gasoline into lemonade bottles from a big, rusty fuel barrel on the foredeck, using a rubber hose. Inside, the breakfast table had been set, but there was no time to eat. The landing of the grave-searchers was busily being prepared, as Boyarsky was threatening that the sea might soon get rough again. Only George, with aristocratic unconcern, sat sipping a cup of tea in the otherwise empty mess room. The corridors teemed with foot traffic. The hum of electric motors resonated through the steel vessel as the deck crane deposited a huge stack of wooden beams and planks from the hold into the landing craft. For protection against bears, the Ivanov Bay group would be constructing a hut for their stay. On deck, the atmosphere was frenzied and tension was palpable, with good-byes adding to the din of cargo handling.

Freed from all its cables, our landing craft, a red steel barge five meters long, danced merrily atop the waves. Once the entire Ivanov gang had climbed down the rope ladders, the droning plashkot sailed rapidly into the haze. Bundled up in gear as if ready to go ashore myself, I stood in a light rain atop Kiriev’s bridge and followed the progress of the landing through binoculars. A trio of long, rustbrown walruses glided by the red craft through the pale blue sea. It was easy to distinguish their bristling snouts, which spit out a spray of condensation and water when the animals are surfacing. It was +4°C. Novaya Zemlya was just a dark strip of land, the elevations above ca. 100 m disappearing into the low clouds. There was little snow.

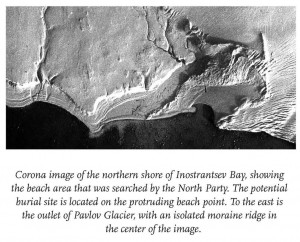

By 11:15 a.m., the Ivanov group was ashore. The landing craft delivered a second load and was hoisted aboard. Kiriev raised anchor, but would not sail towards Ice Harbor. It had been decided to seek shelter from a new storm in Inostrantsev Bay, on the west coast of the island. Excitement swept over the ship when, at noon, we saw the first unobtrusive iceberg float by: the entire oyage so far had not provided this many sights. The silent flotilla of blue sculptures grew by the hour, indicating the proximity of calving glaciers. Our arrival in Inostrantsev Bay was estimated for 3:00 p.m. The plan calls for a reconnaissance sortie with two groups along the beaches of the bay, to search for cairns. Boyarsky requests that we be specifically alert for objects indicating the presence of the ancient Pomors and the Nazis, who operated in greatest secrecy on these shores during their Arctic campaigns. The approaching landing put us back on the alert. Bas distributed ammunition for the rifles and reviewed the arms discipline. “Should a polar bear come after us and we decide to fire at him,” he instructed us, “we’ll follow our firing-range routine. The shooter kneels down and someone else counts the bear’s approach: fifty meters… forty meters… thirty meters… Don’t stare at the bear, but focus on his chest or on his shoulder. There will be three cartridges in the magazine. For reasons of safety, do not keep a cartridge in the chamber. Remember, the second man keeps additional ammo at the ready.”

Self-sufficiency is imperative for one venturing out in the Arctic, and it was high time to get my gear in order. (“Coming along?” Anton, our film director, would tell the viewer. Small kids start crying, young women turn off the TV.) What do I need? After polar bears, the unpredictable weather, which can change from quiet to severe in half an hour, is the greatest challenge. The land is barren and provides no shelter. There is no snow in which the stranded traveler could dig a shelter against the piercing winds. To be lightly equipped and able to move about swiftly, I packed the thin, reinforced Gore-Tex cover of the Navy-issue sleeping bag and a small stove, with a one-liter bottle of gasoline, enough for two weeks. High-grade gasoline is harder to come by in these parts of the world than diesel or kerosene but more practical because kerosene fuel oil has a flash point well above 40°C and won’t ignite easily in low-temperature environs. I took my down jacket, wrapped in a plastic bag, so I could leave my sleeping bag on board. I took wax for my boots, packages of instant soup, chocolate milk, and mashed potatoes. There would be sufficient meltwater on land, but just to be sure, I filled my canteen. On a waist belt, I carried the dagger and a pouch containing flare gun, GPS, a set of waterproof-packed batteries, a notebook with waterproof paper, and a pencil. I took some extra film and decided where to put everything: the rain gear fortunately has plenty of zippered pockets to stow away the many little items I need to keep track of.

The sea was calm: smooth as glass. The landing craft glided over in fifteen minutes and at 4:00 p.m. ground onto the steep, gravel beachfront. The sailors kept the engine running to maintain a solid lock while we disembarked. In clouds of smoke and steam, we climbed the steep ridge of loose gravel. Then, after reversing the propeller’s motion, the plashkot quickly retreated into the fog.

The Innovation of Population Forecasting Methodology in the Inter-war Period: The Case of the Netherlands

4.1 Introduction

4.1 Introduction

The foundations of the model of population dynamics that was to dominate population forecasting methodology throughout the greater part of the 20th century were laid by the English economist Edwin Cannan (1861-1935). By the end of the 1930s, it had become the new standard model for forecasting national populations. After the Second World War, the model became known as the Cohort-Component Projection Model (CCPM).[i]

However, this does not mean that the introduction and general acceptation of the new methodology was a matter of veni, vidi, vici. On the contrary, almost three decades passed between its emergence in 1895 and its reinvention and general application for national population forecasting purposes in the mid-1920s.

Read more

El Salvador en transición

El acuerdo de paz firmado el 16 de enero de 1992 entre el gobierno y el movimiento rebelde FMLN puso fin a más de diez años de guerra civil en El Salvador. En este capítulo trataré los antecedentes de esa guerra y el desarrollo y el proceso que llevaron al acuerdo de paz. El énfasis radica en los cambios entre el estado, los partidos políticos y las organizaciones de la sociedad civil. De esta manera surge una imagen del contexto social en que nacieron las organizaciones de ayuda para el desarrollo y del espacio donde estas organizaciones intervinieron. Para dar una imagen global del contexto histórico de la guerra civil, me adentraré primero en algunos importantes desarrollos políticos y económicos que tuvieron lugar entre 1870 y 1970. Trataré después a los principales actors en los decenios anteriores a la guerra civil. Estos eran, entre otros, los (nuevos) partidos políticos, los militares, las organizaciones paramilitares, la iglesia y los movimientos revolucionarios. Seguirá a continuación el tema de la guerra civil, en el que se prestará atención al papel desarrollado por el FMLN, los partidos políticos, el gobierno salvadoreño y los Estados Unidos. Para terminar, se tratará el acuerdo de paz. Esbozo allí los cambios principales que tuvieron lugar en base a la llamada ‘triple transición’ en El Salvador.

Una historia de exclusión

Para Torres Rivas y González Suárez (1994:12), la guerra civil fue el resultado de un largo período de exclusión social, económica y política a la que fueron sometidos grandes sectores de la población. Este proceso tuvo profundas raíces históricas y llevó en los años sesenta y setenta a la polarización y al agravamiento de la crisis en la sociedad salvadoreña. La crisis social que surgió en estos años no puede explicarse sólamente como el resultado de la influencia de los Estados Unidos o de la oposición de la poderosa oligarquía agraria a las reformas (Carrière y Karlen, 1996:368). Hubo una combinación de factores internos y externos que en los años anteriores a la guerra impidió una modernización a fondo de la política, la economía y la sociedad. La mayoría de los análisis de la guerra civil salvadoreña comienzan en la segunda mitad del siglo pasado. Este fue el período en el que se desarrollaron el cultivo y la exportación de café a gran escala. El café tuvo una influencia definitiva en las relaciones sociales salvadoreñas en gran parte de ese siglo. El cultivo y la exportación de este producto fueron la reacción ante la disminución de la demanda internacional de indigo, un colorante azul oscuro de textiles que constituía hasta entonces el principal producto de exportación de El Salvador. Las mejores condiciones para el cultivo del café se dan en suelos situados entre los 500 y los 1.500 metros sobre el nivel del mar. Una gran parte de los suelos adecuados para el cultivo del café eran propiedad comunal, entre otros de pueblos indígenas. El gobierno dirigido (desde 1871) por los liberales era partidario de la comercialización en el usufructo de los suelos y abolió la propiedad comunal de la tierra en las reformas de 1881 y 1882. Un número relativamente pequeño de familias (entre ellas las dedicadas antes al cultivo del indigo) compró grandes extensiones de tierra, dominando rápidamente la producción y el comercio del café. Read more

De werkvloer van het Koninkrijk. Over de samenwerking van Nederland met de Nederlandse Antillen en Aruba. Inhoudsopgave

In 1654 wordt door de vergadering van de Heren XIX, het bestuur van de West-Indische Compagnie, verzucht dat het behouden van Curaçao een te grote last betekent voor de Compagnie. De banden met Nederland blijven. Eeuwen later, in 1998, verschijnt een bundel opstellen Breekbare banden en in 2001 luidt de titel van een departementaal gedenkboek Knellende Koninkrijksbanden. In De werkvloer van het Koninkrijk wordt verslag gedaan van de samenwerking tussen Nederland en de ‘warme delen’ van het Koninkrijk in de periode dat min of meer vanzelfsprekend werd overeengekomen dat de Nederlandse Antillen en Aruba deel uit blijven maken van het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden.

In 1654 wordt door de vergadering van de Heren XIX, het bestuur van de West-Indische Compagnie, verzucht dat het behouden van Curaçao een te grote last betekent voor de Compagnie. De banden met Nederland blijven. Eeuwen later, in 1998, verschijnt een bundel opstellen Breekbare banden en in 2001 luidt de titel van een departementaal gedenkboek Knellende Koninkrijksbanden. In De werkvloer van het Koninkrijk wordt verslag gedaan van de samenwerking tussen Nederland en de ‘warme delen’ van het Koninkrijk in de periode dat min of meer vanzelfsprekend werd overeengekomen dat de Nederlandse Antillen en Aruba deel uit blijven maken van het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden.

Het eerder dominerende dekolonisatie perspectief van aanstaande onafhankelijkheid is daarmee van de baan. De teneur van de samenwerking in Koninkrijksverband verandert en wordt meer en meer aangestuurd onder het adagium ‘blijvend, niet vrijblijvend’. De geldstroom uit Nederland naar de Nederlandse Antillen en Aruba valt als ontwikkelingshulp niet te legitimeren en heeft averechtse gevolgen. De formeel verankerde gelijkwaardigheid van de partners manifesteert zich in de praktijk van de verhoudingen steeds vaker in een spagaat van ongelijkheid waarvan Nederland de maat bepaalt.

Toch is Nederland niet bij machte te voorkomen dat een ‘sociale kwestie’ op Curaçao onstaat die ‘overloopt’ naar ‘Antillen-gemeenten’ in Nederland. De moraal van het Koninkrijk is niet zo helder als voorheen. Wat zal het Koninkrijk voor de Caribische landen nog kunnen betekenen wanneer grenzen vervagen en Nederland steeds meer deel uitmaakt van Euroland?

Het boek De werkvloer van het Koninkrijk (Rozenberg Publishers, 2002) nu online:

De werkvloer van het Koninkrijk I: Inleiding

De werkvloer van het Koninkrijk II: Kernbegrippen

De werkvloer van het Koninkrijk III: Spagaat van ongelijkheid

De werkvloer van het Koninkrijk IV – Ontsporing van de samenwerking

De werkvloer van het Koninkrijk V – Formaat van de samenwerking

De werkvloer van het Koninkrijk VI – De vertegenwoordigheid van Nederland

De werkvloer van het Koninkrijk VII – Een doekje voor het bloeden

De werkvloer van het Koninkrijk VIII – De moraal van het koninkrijk

De werkvloer van het Koninkrijk IX – Edward Heerenveen – Epiloog

Plus: Video Antilliaans verhaal – Aflevering 1

Lammert de Jong (1942 – 2024) studeerde aan de Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam waar hij promoveerde. De titel van zijn proefschrift was Bestuur en publiek. Vanaf 1985-1998 was hij gedurende tal van jarenwerkzaam als Vertegenwoordiger van Nederland in de Nederlandse Antillen. Daarvoor werkte hij als wetenschappelijk medewerker bestuurskunde in Lusaka, Zambia (1972-1976). In de volksrepubliek Benin was hij directeur (veldleider) van de Ontwikkelingsorganisaties Stichting Nederlandse Vrijwilligers (1980-1984). Als adviseur Koninkrijksrelaties bij het ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties heeft hij 2000 zijn ambtelijke loopbaan afgesloten. Read more