Will Trump’s Policies Wreak Havoc On The US And Global Economies?

Gerald Epstein is Professor of Economics and a founding Co-Director of the Political Economy Research Institute (PERI) at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst

With the midterm elections rapidly approaching, many Americans will start thinking more and more about the economy before they decide how to cast their votes. In this context, Trump’s claim that the US economy under his administration is the “greatest in history” needs to be thoroughly and critically examined in order to separate facts from myths. How much of the ongoing “recovery” is being felt by average American workers? And what about Trump’s escalating trade war with China, which is already beginning to impact American consumers and various US manufacturers, while making European firms nervous? In this exclusive interview, Gerald Epstein, professor of economics and co-director of the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, clears the air on several myths and misconceptions about the developments that Trump has tried to frame as an “economic miracle.”

C.J. Polychroniou: Trump likes to boast about an economic revival of historic proportions under his administration, which includes a strong labor market, a robust stock market, and a 4 percent GDP rate. What are the facts and myths about Trump’s alleged economic miracle? Give us the full story.

Gerald Epstein:Trump is a gross exaggerator who loves to construct stories. When it comes to his claims about an economic miracle under way during his administration, I think my friend and colleague John Miller in the economics department at Wheaton College put it best in a September 30 presentation at the University of Massachusetts Amherst: “Compared to the standard of U.S. economic performance since 1948, we have been living through an economic expansion that has been historically long, historically slow, and that has done historically little to improve the lot of most people.”

It is safe to say, as Miller and many other economists show, slashing corporate taxes has not generated an investment boom or a stock market boom. Data show that during the second quarter of 2018, housing investment continued to go down, and spending on new equipment, the largest component of investment, grew only half as quickly as it had at the end of 2017, prior to the tax cut. As the data discussed by Josh Bivens of the Economic Policy Institute show, business investment in structures such as office buildings and factories did increase far more quickly than before the tax cut, but most of that went into oil and gas drilling which resulted from higher world energy prices.

What’s the explanation for S&P 500 and Dow setting all-time records under Trump, and what impact do stock market trends have on the life and well-being of average Americans?

It is true that the stock market has increased since Trump was elected, but it has been on an upswing since the recession bottomed out in 2009. In fact, stock prices (the S&P 500 adjusted for inflation) increased just 2.1 percent from Jan. 1 to Sept. 1, 2018 — far slower than earlier in the expansion, and the near double-digit increase during the 1990s expansion.

Only in the third week of September did the S&P 500 Stock Index and the Dow Jones Index finally top their January 2018 highs.

Still, it is clear that since Trump was elected, financial investors have been quite happy and optimistic. The Republican agenda of tax cuts and deregulation have significantly increased corporate profits and the expectations of further corporate profits, and these drive up stock prices.

But most stocks are owned by the very wealthy. According to Edward Wolff, the richest 10 percent of the population own close to 90 percent of all stocks. So when the stock market goes up in value, it is the already very rich that mostly benefit. Read more

De verborgen heimwee van Léo Malet. Een speurtocht in Parijs

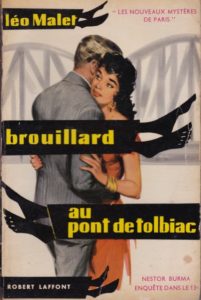

De Franse schrijver Léo Malet (1909-1996) schreef in de jaren veertig, vijftig en zestig tientallen detectiveromans. Na Georges Simenon was hij de best verkochte detectiveschrijver in Frankrijk. Voor de Tweede Wereldoorlog was hij actief als anarchist en betrokken bij de surrealistische beweging rond André Breton. Zijn bekendste boek is Brouillard au Pont de Tolbiac (1956), wat zich afspeelt in het 13e Arrondissement in Parijs. Wie in het voetspoor van Malet de wijk wil doorkruisen, treft een stadswijk aan die in ruim een halve eeuw tijd enorm van karakter is veranderd. De vraag is of dat allemaal ten goede is.

Een warme zomerse dag in Parijs, een aantal jaren geleden. Ik sta op de plek waar de Rue de Tolbiac overgaat in de Pont de Tolbiac, in het 13e Arrondissement, aan de oostkant van Parijs, langs de Seine. Het eerste gedeelte van de brug overspant een aantal treinsporen en na de kruising met de Port de la Gare, volgt het tweede gedeelte over de Seine. Helaas is de oorspronkelijke gietijzeren brug in de jaren tachtig van de vorige eeuw vervangen door een moderne betonnen constructie.

Op deze plaats zouden in 1936 een aantal anarchisten een geldloper van het nabij gelegen koelhuis Entrepôts Frigorifiques beroofd hebben. Van de geldloper, het geld of de daders is nooit een spoor terug gevonden. Pas twintig jaar later zou de zaak opgelost worden. Dat is althans het gegeven in de roman Brouillard au Pont de Tolbiac (1956) van Léo Malet.

In deze roman wordt privédetective Nestor Burma – voormalig anarchist – twintig jaar later door een oude kameraad getipt over de zaak van de beroofde geldloper. Burma verdiept zich in de zaak en wordt vervolgens geconfronteerd met zijn anarchistische verleden, met personen en gebeurtenissen die hij al lang had verdrongen.

Geweld

In 1936 is de jonge Burma een krantenverkoper in het 13e Arrondissement en logeert hij in het Foyer Végétalien – wat werkelijk bestaan heeft: 182 Rue de Tolbiac – waar veganisten, anarchisten en andere wereldverbeteraars een goedkoop onderkomen kunnen vinden. Op de slaapzaal wordt onder de anarchisten gediscussieerd over het gebruik van geweld tegen de maatschappij en tegen personen. De namen vallen van Callemin, Soudy en Garnier, enkele van de zogenaamde Autobandieten. Deze groep anarchisten, ook bekend als de Bende van Bonnot, zorgde in 1911 en 1912 voor onrust en paniek in Parijs en omstreken, vanwege enkele gewelddadige overvallen. Het geld was bestemd voor de anarchistische beweging.

Burma is tegen het gebruik van geweld, maar anderen menen dat geweld niet kan worden uitgesloten. De overval op de geldloper bij de Pont de Tolbiac is het gevolg. Wanneer Burma zich twintig jaar later op de oude zaak stort, lijkt een confrontatie met vroegere kameraden onvermijdelijk.

Idealen

In het boek worden anarchisten niet stereotiep, karikaturaal neergezet als harteloze fanatici met cape, hoed en bom. Het zijn gewone figuren met idealen, sappelend om de kost te verdienen. Maar bij sommigen speelt de geldzucht op. Anarchistische idealen worden opzij gezet en wellicht komt hun ware karakter boven. Brouillard au Pont de Tolbiac is in de eerste plaats bedoeld als een spannend boek, maar het heeft een tweede laag. De wijze waarop Malet de gebeurtenissen laat ontrollen en de ontknoping van het verhaal, zijn een afrekening van Burma met de handelswijze van vroegere kameraden. Dat Burma daarbij geen geweld hoeft te gebruiken, komt niet alleen goed uit, maar geeft de opvattingen van Burma – maar ook die van Malet zelf – weer.

Julia Wouters ~ De zijkant van de macht – Waarom de politiek te belangrijk is om alleen aan mannen over te laten

De politiek is te belangrijk om alleen aan mannen over te laten – Els Borst zei het al in 1998 -, maar vreemd genoeg neemt het aantal vrouwen in de politiek juist af. Terwijl de maatschappelijke betrokkenheid en het activisme onder vrouwen de laatste jaren sterk is gegroeid, hebben weinigen de ambitie om de politiek in te gaan. “Vrouwen houden niet van een slangenkuil.” Zo hadden van de 28 partijen die meededen aan de landelijke verkiezingen van 2017 er slechts vier een vrouwelijke lijsttrekker. Hoe komt dat?

In ‘De zijkant van de macht’ zoekt Julia Wouters naar een verklaring, waarbij zij put uit haar eigen kennis en ervaringen, (internationale) onderzoeken en de ervaringen van politici zelf. Zij analyseert op welke manieren vrouwen worden benadeeld en geeft veel praktische tips in een wereld die mannen en mannelijkheid als maatstaf neemt. Wouters meest effectieve strategie: Handhaaf je als vrouw binnen de (mannelijke) politiek arena en gebruik je invloed om voor de lange termijn die arena zo te veranderen dat vrouwen zich er ook thuis voelen.

In het eerste hoofdstuk geeft Wouters een uitgebreid overzicht van hoe de positie van vrouwen in de politiek zich sinds de invoering van het vrouwenkiesrecht heeft ontwikkeld. Anna de Waal, Joke Smit, Neelie Kroes, Jeltje van Nieuwenhoven, Elske ter Veld, Annemarie Jorritsma, Eveline Herfkens, Hedy d’Ancona zijn van de generatie waarbij het van belang was gemeenschappelijke belangen te hebben en onderling solidair te zijn. Vrouwen die vanaf de negentiger jaren in de politiek gingen zoals Femke Halsema, Marianne Thieme en Sadet Karabulut hadden niet langer een specifieke vrouwenagenda, maar veel eerder een partij-ideologische en individualistische agenda: zij wilden vooral hun eigen kracht bewijzen.

Maar er is nog veel te doen om vrouwen een gelijkwaardige positie te geven. Er is nog steeds sprake van alledaags seksisme en hardnekkige vooroordelen. In de politieke arena is het nodig dat meer vrouwen zich inzetten om de positie van vrouwen te verbeteren.

Want de traditionele politiek heeft aan geloofwaardigheid verloren; een nieuwe generatie politici moet verandering en vernieuwing creëren en vanzelfsprekend kunnen vrouwen hierin een belangrijke rol spelen, aldus Wouters. Read more

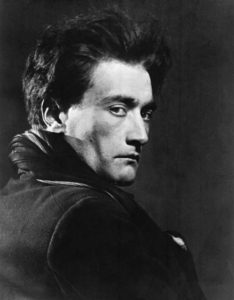

Islamic State & The Artaudian Theatre Of Cruelty

Abstract

Intrigued by the idea that the Islamic State’s media is performing Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty, we questioned in this article whether Islamic State’s use of media does indeed compare to the hellish visions of the notorious French dramaturge, and consequently ask ourselves, if so, how we should interpret and give meaning to the eventual connection between two subjects that seem so far apart, and yet so close to each other: the Theatre of Cruelty and the gruesome religiously inspired videos of Islamic State.[i] The results of our analysis confirm significant parallels between the Theatre of Cruelty and the cruel videos of Islamic State. Considering the fact that the message of cruelty is central to many of their videos, we conclude that ‘Islamic State’s media productions indeed implement the characteristics underlying Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty.’ But what does all this mean? Cruelty and violence are indeed elements of human being’s nature. Humankind has to embody it in one way or the other, and from that perspective, it is much better to incorporate these darker sides of men in the metaphysical sphere. We are deliberately speaking here of humankind, irrespective of religious or ethnic background, because there are Westerners and Easterners that have learnt this dear lesson: acknowledging the dark side of men and expressing it in art.

Key words: # Islamic State # Artaud # Theatre # Propaganda # Cruelty # Hermeneutics # Interpretation

1 Introduction

‘Artaud, a sickly child twisted further by the shock of World War I, wanted his actors to “assault the senses” of the audience, shocking parts of the psyche that other theatrical methods had failed to reach. Well, IS has read the book. It’s been obvious since September 11 that we’re living in an age of vicious political theatre. That’s what ‘terrorism’ is: the manipulation of large populations by shock and awe and ‘liberating unconscious emotions’’ (to quote Artaud).’[ii]

‘If the attacks on the Twin Towers used the iconography of the Hollywood action blockbuster, the beheadings in the desert evoke drama far more ancient – Old Testament strife, Hellenic legend. [..]It may sound unlikely, but ISIS is carrying out in extremis the program of the ‘Theatre of cruelty’ of the influential French dramaturgedemiurge Antonin Artaud.’[iii]

In the summer of 2014, the geopolitical stage was shaken by the Islamic State videos. Starting off a series of terrifying communiqués with a video of the beheading of journalist James Foley in A message to America, Islamic State quickly set a new standard for extremists’ use of media as a propaganda tool. Now that the extreme display of violence has become the hallmark of Islamic State terror, certain journalists have suggested a link between these brutal videos and dramatist Antonin Artaud (1896-1948) and his ‘Theatre of Cruelty’. We were intrigued by the idea that the correspondence between Islamic State’s media outlets and Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty might actually go beyond the shared predominance of cruelty and have taken the suggestion made by Sakurai as a cue to research whether Islamic State’s use of media does indeed compare to Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty on a more fundamental level. And consequently ask ourselves how, if so, we should interpret and give meaning to the eventual connection between two subjects that seem so far apart, and yet so close to each other: the Theatre of Cruelty and the gruesome religiously inspired videos of Islamic State.

The research done is comparative in nature. By comparing and contrasting the principal underlying ideas, the audience/performance relation, and the performance itself of Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty and Islamic State’s video productions, we hope to arrive at a detailed and nuanced understanding if and if yes, how Islamic State and Artaudian theatre relate to each other. The possible connection between both being eventually confirmed, we will consequently dwell on the meaning of such connection. Read more

Mati Shemoelof ~ …reisst die Mauern ein zwischen ‘uns’ und ‘ihnen’

Onlangs verscheen van dichter, auteur, uitgever, en bekende stem in de Arabisch-joodse Mizrahi-Beweging Mati Shemoelof …reisst die Mauern ein zwischen ‘uns’ und ‘ihnen’. Tekst en gedichten wisselen elkaar af.

Het heeft Mati Shemolof enige tijd gekost om te begrijpen dat de geschiedenis van zijn familie uit de geschiedenisboeken is verwijderd en in de Israëlische samenleving is gemarginaliseerd. Je komt in een soort van diaspora terecht als je van Arabische afkomst bent, terwijl Israël een thuis zou moeten zijn voor joden die naar een joodse staat emigreerden, aldus Shemoelof. Hij nam in 2007 dan ook het initiatief om Echoing Identies: Young Mizrahi Anthology uit te geven met teksten van de derde generatie Mizrachi. Door al zijn ervaringen is Mati Shemoelof zich bewust geworden van de diaspora van anderen, of het nu Syriërs zijn in Berlijn, Afghanen, Libiërs of Oost-Europeanen; maar vooral de diaspora van de Palestijnen uit de periode 1948 en 1967 raakt hem.

Shemoelof’s Perzische grootvader werd in het begin van de 20e eeuw gedwongen uit Mashhad (Iran) naar Haifa te emigreren, dat toen nog bij Palestina hoorde. Haifa van voor 1948 was een moderne stad, waar verschillende culturen vreedzaam naast elkaar leefden, waar zijn opa goed zaken kon doen en vrij was. Maar deze Palestijnse geschiedenis van Haifa is niet meer bekend.

De geschiedenis van zijn moeder is kenmerkend voor een familie van Mizrachim, voor joden met een Arabische cultuur en taal. Ze waren goed geïntegreerd in Irak en over het algemeen seculier. Zij werden echter in 1951 gedwongen van Bagdad naar Israël te emigreren, net als zo’n 120.000 andere Iraakse-joodse burgers, met achterlating van al hun bezit. Dat was onderdeel van de deal tussen Irak en Israël: de zionistische beweging kreeg arbeidskrachten en Irak bezit. Maar eerder had al de Farhud in Irak plaatsgevonden: op 1 en 2 juni 1941 vond een Pogrom plaats tegen joden in Bagdad, waarbij tussen de 150 en 200 doden vielen en van velen hun bezit werd afgenomen.

Nu zijn in Israël muren rondom Palestijnen, maar ook om de Arabische joden is een muur geplaatst. En toch zijn vele Mizrachi, die in armoede leven, niet solidair met de Palestijnen.

Om je te verhouden tot al die muren in Israël, in – en extern, is moeilijk en maakte Mati Shemoelof tot activist van de Mizrachi-Beweging, die strijdt voor sociale rechtvaardigheid en erkenning van identiteit. De Mizrachi-Beweging onderzoekt met name de verwantschap tussen hun identiteit en die van de Palestijnen en de Arabische wereld. Read more

Human Rights, State Sovereignty, And International Law

We live in an era where virtually every government on the planet claims to pay allegiance to human rights and respect for international law. Yet, violations of human rights and plain human decency continue to occur with disturbing frequency in many parts of the world, including many allegedly “democratic” countries such as the United States, Russia, and Israel. Indeed, Donald Trump’s immigration policy, Putin’s systematic repression of dissidents, and Israel’s abominable treatment of Palestinians seem to make a mockery of the principle of human rights. Is this because “faulty” forms of government or because of some Inherent tension between state sovereignty and human rights? And what about the international regime of human rights? How effective is it in protecting human rights? Richard Falk, a world renowned scholar of International Relations and International Law sheds light into these questions in the exclusive interview below with C. J. Polychroniou.

Richard Falk is Alfred G. Milbank Emeritus Professor of International Law, Politics, and International Affairs at Princeton University and the author of some 40 books and hundreds of academic articles and essays. Among his most recent books are A New Geopolitics (to be published in December 2018); Palestines’s Horizon: Toward a Just Peace (2017); Humanitarian Intervention and Legitimacy Wars: Seeking Justice in the 21st Century (2015); Chaos and Counterrevolution: After the Arab Spring (2014); and Path to Zero: Dialogues on Nuclear Dangers (2012).

C. J. Polychroniou: Richard, you taught International Law and International Affairs at Princeton University for nearly half a century. How has international law changed from the time you started out as a young scholar to the present?

Richard Falk: You pose an interesting question that I have not previously thought about, yet just asking it makes me realize that this was a serious oversight on my part. When I started thinking on my own about the role and relevance of international law during my early teaching experience in the mid-1950s, I was naively optimistic about the future, and without being very self-aware, I now understand that I assumed that moral trajectory that made the future work out to be an improvement on the past and present, that there was moral progress in collective behavior, including at the level of relations among sovereign states. I thought of the expanding role of international law as a major instrument for advancing progress toward a peaceful and equitable world, and endeavored in my writing to encourage the U.S. Government to align its foreign policy with international law, arguing, I suppose in a liberal vein, that such alignment would promote a better future for all while at the same time being beneficial of the United States, especially given the overriding interest in avoiding World War III.

My views gradually evolved in more critical and nuanced directions. As my interests turned toward the dynamics of decolonization, I came to appreciate that international law had legitimized European colonialism, and the exploitative arrangements that were imposed on the countries of the global south. I realized that the idealistic identification of international law with peace and justice was misleading, and at best only half of the story. International law was generated by the powerful to serve their interests, and was respected only so long as vital interests of these dominant states were not threatened.

The Vietnam War further influenced me to adopt a more cautious view of international law, and even more so, of the United Nations. I opposed the war from the outset from the perspective of international law, citing the most basic prohibitions on intervention in the internal affairs of sovereign states and the core prohibition of the UIN Charter against all recourses to aggressive force. I did find it useful to put the debate on Vietnam policy in a legal format as the country was then under the sway of liberal leadership, although tinged with Cold War geopolitics and ideology. The defenders of Vietnam policy, motivated by Cold War considerations, relied on legal apologetics as well as claims that it was important for world order to contain the expansion of Communist influence, and that the adversary in Vietnam was China rather than North Vietnam. The legal debate to which I devoted energy for ten years convinced me that international law on war/peace issues was subordinated to geopolitics including by the Western democracies, and that even so, legal counter-arguments were always available to governments eager to disguise their reliance on geopolitical priorities. International law remains useful and even necessary for the routine transnational activities of people and governments, stabilizing trade and investment relations, but often in ways that favor the rich, and issues pertaining to questions of safety, communications, and tourism exhibit a consistent adherence to an international law framework. Read more