New World, New Hope: The Struggle For A Free Western Sahara Continues

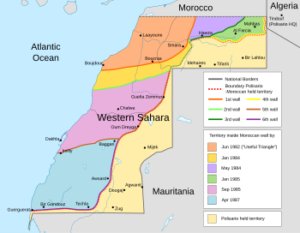

Western Sahara – Map: en.wikipedia.org

06-27-2024 ~ The Sahrawi freedom movement Polisario continues the armed struggle against Morocco, which uses Israeli spyware and lures the West with trade opportunities to turn a blind eye to the occupation of Western Sahara. Many Sahrawis see new hope in a new multipolar world order that is not dominated by the United States and the West.

Life under occupation is a constant struggle. This is continually expressed at the international media conference in a refugee camp in Western Sahara. The conference takes place from May 1–5 and is organized by the Sahrawi Union of Journalists and Writers (UPES).

Western Sahara is occupied by Morocco, a country where King Muhammad VI has full control over Morocco’s armed forces, judiciary, and all foreign policy.

In Western Sahara, the Moroccan monarchy violates the human rights of the Sahrawi people. Children suffer from malnutrition, journalists are thrown in prison, and international observers are denied access to the occupied territories.

Morocco’s colonization of Western Sahara has been going on since 1975; however, the occupation receives little attention from the international community. Through the occupation, Morocco offers trade opportunities to Western companies while the Moroccan intelligence service uses Israeli spyware to monitor the Sahrawis.

But the revolutionary Sahrawi freedom movement—Polisario Front—is not giving up: In 2020, Polisario resumed its armed struggle against Morocco. The Sahrawis hope that a new world order, not dominated by the West, will open up new possibilities in the fight for a free and independent Western Sahara.

Occupied Land

The media conference takes place in Wilayah of Bojador, one of five Sahrawi refugee camps located in Algeria on the border with Western Sahara. Algeria has given the area to Polisario, which administers the refugee camps.

Thus, you could say that Western Sahara is divided into three areas. There are the occupied territories of Western Sahara, where Morocco is in power. There are the liberated areas of Western Sahara, where Polisario is in power. And then there are the refugee camps in Algeria, where Polisario is also in power. Read more

Trix van Bennekom ~ Halte Hausdorff

06-24-2024 ~ Het leven van David Hausdorff. Jood, huisarts en Rotterdammer.

06-24-2024 ~ Het leven van David Hausdorff. Jood, huisarts en Rotterdammer.

‘Sint-Petersburg, zondagmiddag 13 maart 1881’. Dat Trix van Bennekom de biografie van David Hausdorff begint met deze regel, illustreert haar aanpak. Een aanpak die we kennen van haar boek Abraham. Kroniek van een politieke dynastie (2018). De combinatie van een persoonlijke geschiedenis en de grote geschiedenis levert ook nu weer een bijzonder boek op.

Op die dertiende maart in 1881 kwam tsaar Alexander II bij een aanslag om het leven. Al kwamen de daders uit een revolutionaire groepering, de Nihilisten, de Joodse gemeenschap in Rusland kreeg de schuld. Drie jaar lang werden Russische Joden door volksmassa’s mishandeld en vermoord. De eerste grote pogroms in de moderne tijd.

Vanuit Rusland en aangrenzende gebieden kwam een grote stroom vluchtelingen op gang. De meeste vluchtelingen wilden naar Amerika.

Rotterdam kreeg de bijnaam ‘Warschau aan de Maas’, zo veel mensen kwamen vanuit het Oosten in de hoop in te kunnen schepen naar het Gouden Land.

Tussen 1818 en 1914 verhuisden 2,5 miljoen Joden uit Oost-Europa naar de Verenigde Staten.

Ook een deel van de familie Hausdorff, woonachtig in Polen, dicht bij de Russische grens, besloot naar het Westen te gaan. Het geweld kwam steeds dichterbij.

Na eerst in Duitsland gewoond te hebben, gingen twee zonen Hausdorff in 1883 naar Rotterdam. Daar wordt op 2 november 1901 David Hausdorff geboren.

Het is verleidelijk om maar te blijven vertellen over geschiedenis die de achtergrond vormt voor het verhaal over deze huisarts. En dan moet je nog beginnen aan de verhalen over de Joodse gemeenschap in Rotterdam voor de oorlog, over de oorlogsjaren, over de onderduik van het gezin Hausdorff vanaf 1943, over de wederopbouw van diezelfde Joodse gemeenschap na de oorlog.

Wil je aan de hand van een citaat laten zien hoe Van Bennekom in één alinea de stemming in de Joodse gemeenschap vlak na de oorlog weet samen te vatten:

‘De Duitse bezetter had in Nederland niet alleen meer dan 100.000 Joden de dood ingejaagd, ook het eeuwenoude Joodse leven was weggevaagd. Synagogen, ziekenhuizen, scholen, weeshuizen, bejaardenhuizen, bedrijven, woonhuizen, winkels; alles was in beslaggenomen en geplunderd, religieuze, sociale en culturele organisaties waren opgeheven. Waar te beginnen? En had het nog wel zin de Joodse gemeenschap opnieuw op te bouwen? De anti-Joodse stemming die in de eerste maanden na de bevrijding in Nederland heerste, deed het ergste vrezen voor de toekomst: zouden Joden niet altijd tweederangsburgers blijven?’

Maar verstandiger is het om nu maar gewoon te stoppen en te zeggen: lezen!

Studio Rashkov, Rotterdam, 2024

ISBN 9789083320434

Modern (Mis)interpretations Of Clean Slates

Michael Hudson

06-19-2024 ~ Today’s creditor-oriented ideology depicts the archaic past as much like our own world, as if civilization was developed by individuals thinking in terms of modern orthodoxy.

Why were Clean Slates so important to Bronze Age societies? From the third millennium in Mesopotamia, people were aware that debt pressures, if left to accumulate unchecked, would distort normal fiscal and landholding patterns to the detriment of the community. They perceived that debts grow autonomously under their own dynamic by the exponential curves of compound interest rather than adjusting themselves to reflect the ability of debtors to pay. This idea never has been accepted by modern economic doctrine, which assumes that disturbances are cured by automatically self-correcting market mechanisms. That assumption blocks discussion of what governments can do to prevent the debt overhead from destabilizing economies.

The Cosmological Dimension of Clean Slates

Mesopotamia’s concept of divine kingship was key to the practice of declaring Clean Slates. The prefatory passages of Babylonian edicts cited the ruler’s commitment to serve his city-god by promoting equity in the land. Myth and ritual were integrated with economic relations and were viewed as forming the natural order that rulers were charged with overseeing; in this context, canceling debts helped fulfill their sacred obligation to their city-gods. Commemorated by their year-names and often by foundation deposits in temples, these amnesties appear to have been proclaimed at a major festival, replete with rituals such as Babylon’s ruler raising a sacred torch to signal the renewal of the social cosmos in good order—what the Romanian historian Mircea Eliade called “the eternal return,” the idea of circular time that formed the context in which rulers restored an idealized status quo ante. By integrating debt annulments with social cosmology, the image of rulers restoring economic order was central to the archaic idea of justice and equity.

(Mis)Interpreting the Meaning of ‘Freedom’

The Hebrew word used for the Jubilee Year in Leviticus 25 is dêror, but not until cuneiform texts could be read was it recognized as cognate to Akkadian andurarum. Before the early meaning was clarified, the King James Version translated the relevant phrase as: “Proclaim liberty throughout all the land, and to all the inhabitants thereof.” But the root meaning of andurarum is to move freely, as running water—or (for humans) as bondservants liberated to rejoin their families of origin.

The wide variety of modern interpretations of such key terms as Sumerianamargi, Akkadian andurarum and misharum, and Hurrian shudutu serve as an ideological Rorschach test reflecting the translator’s own beliefs. The earliest reading was by Francois Thureau-Dangin[1], who related the Sumerian term amargi to Akkadian andurarum and saw it as a debt cancellation. Ten years later Schorr (1915) related these acts to Solon’s seisachtheia, the “shedding of burdens” that annulled the debts of rural Athens in 594 BC. The Canadian scholar George Barton[2] translated Urukagina’s and Gudea’s use of the term amargi as “release,” although the Jesuit Anton Deimel[3] rendered it rather obscurely as “security.” Read more

A Historical Case For Why The EU Could Endure For More Than 1,000 Years

06-18-2024 ~ Empires historically possessed a unique ability to organize diversity and successfully rule over people quite different from one another. The national states that succeeded them in Europe were organized on the basis of nationality (real or imagined) where diversity in language, ethnicity, or religion was deemed a barrier to national unity. The negative consequences of celebrating unique national identities became clear after virulent nationalism led to the rise of Nazi Germany and World War II left Europe in ruins.

06-18-2024 ~ Empires historically possessed a unique ability to organize diversity and successfully rule over people quite different from one another. The national states that succeeded them in Europe were organized on the basis of nationality (real or imagined) where diversity in language, ethnicity, or religion was deemed a barrier to national unity. The negative consequences of celebrating unique national identities became clear after virulent nationalism led to the rise of Nazi Germany and World War II left Europe in ruins.

The European Union seeks to prevent this from happening again by restoring the cosmopolitanism, size, and economic clout of a multinational empire but without creating a unitary state in the process.

The EU is designed as a supranational polity where member states retain their national sovereignty and parochial identities but agree to be bound by its laws. They maintain their own armies, independent foreign policies, national parliaments and are free to leave if they so choose. The creation of such a chimeric political beast might appear unpreceded but it is not. The Holy Roman Empire successfully managed the affairs of central Europe by creating a similar composite political structure beginning in 962 under Otto I. In a bid to create unity in the German lands, where the Romans never ruled, the Holy Roman Empire proclaimed itself the successor to the long-dead Roman Empire as the defender of a Catholic Christian Europe. Lacking a single capital and imperial army, it did not seem to be much of an empire. However, its court system resolved disputes between member states, protecting the empire’s free cities and smaller estates (300+) against the more powerful ones. More unusually, it allowed individuals to seek redressals against local rulers who had violated their rights. Its Reichstag or Diet(legislature) met regularly to pass laws that were binding on all members and its emperorship was an elective position. That emperor’s power was limited because the estates within the empire remained responsible for governing their own territories. They were free to make alliances with outside powers as long as they were not detrimental to the empire or posed a danger to public peace.

That the Holy Roman Empire survived for 900 years suggests that it was on to something, and that the EU can be viewed as a secular reincarnation of it—minus only an emperor’s crown and Christian faith as symbols of its unity. However, other than making Charlemagne a symbol of European unity, it is a legacy that is largely unacknowledged and perhaps for good reason. Both the largely forgotten and derided Holy Roman Empire and the EU faced similar structural complexities and solved them in similar ways but the EU’s project was far more substantial—creating a polity that is now the world’s third-largest economy with a population of around 450 million people divided among 27 sovereign nations, which are spread across more than 4.2 million square kilometers. Read more

Migrating Workers Provide Wealth For The World

Vijay Prashad

06-18-2024 ~ Each year, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) releases its World Migration Report. Most of these reports are anodyne, pointing to a secular rise in migration during the period of neoliberalism. As states in the poorer parts of the world found themselves under assault from the Washington Consensus (cuts, privatization, and austerity), and as employment became more and more precarious, larger and larger numbers of people took to the road to find a way to sustain their families. That is why the IOM published its first World Migration Report in 2000, when it wrote that “it is estimated that there are more migrants in the world than ever before,” it was between 1985 and 1990, the IOM calculated, that the rate of growth of world migration (2.59 percent) outstripped the rate of growth of the world population (1.7 percent).

The neoliberal attack on government expenditure in poorer countries was a key driver of international migration. Even by 1990, it had become clear that the migrants had become an essential force in providing foreign exchange to their countries through increasing remittance payments to their families. By 2015, remittances—mostly by the international working class—outstripped the volume of Official Development Assistance (ODA) by three times and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). ODA is the aid money provided by states, whereas FDI is the investment money provided by private companies. For some countries, such as Mexico and the Philippines, remittance payments from working-class migrants prevented state bankruptcy. Read more

Can Teething Predict How Fast You Will Grow?

Brenna Hassett – Photo: en.wikipedia.org

06-17-2024 ~ We know that humans live relatively long lives, and we certainly know that we spend a larger proportion of those lives as children than other species. The question remains: how did we manage to extend this critical period of our growth? When and where did our ancestors start to stretch out the limits of physiology and build that long childhood? And where can we find evidence of this evolutionary process?

The very surprising answer is: in the mouths of babes—specifically, their teeth. But to understand how the timing of teeth tells us the story of, well, us, we need to first put teeth in context: as important milestones on the path to growth.

Different species grow at different rates. How fast you grow is determined by a complicated set of interlocking mechanisms that factor in everything from the mass of the animal to the stability of their environment and has led to the development of a branch of evolutionary biological theory that attempts to disentangle the factors that propel a species from one developmental milestone to the next: ‘life history.’ Understanding a species’ life history has major implications for biology: comparing the rate of growth between two species, for instance, gives us insight into different evolutionary strategies. For Homo sapiens, who have some of the slowest growth on the planet, looking at life history becomes a critical way to address why our species has moved our milestones so far from those of our nearest relatives. Read more