Punishment And Purpose ~ Penal Attitudes

3.1 Introduction

3.1 Introduction

In the previous chapter it has been argued that the practice of legal punishment in itself is morally problematic because it involves actions that would be considered wrong or evil in other contexts. The practice of legal punishment therefore demands a sound (moral) justification. Questions relating to the justification and subsequent goals of punishment have been considered in depth in a number of theoretical and philosophical approaches.

The gamut of theoretical perspectives concerning the justification and goals of punishment has been narrowed down to the general categories of Retributivism, Utilitarianism, Restorative Justice and mixed or hybrid theories. Paying due attention to the main controversies that (still) shape theoretical debate, Chapter 2 elaborated in some detail on the core arguments of these accounts of legal punishment. Radical theories were introduced, but not elaborated, since it was argued that they are of little relevance to the focus of this book, namely the study of attitudes of magistrates within the criminal justice system.

This chapter takes a more detailed look at the concept of penal attitude and its measurement. Penal attitudes are defined as attitudes towards the various purposes and functions of punishment. In turn, these purposes and functions of punishment are deduced from the philosophical theories discussed in the previous chapter. Section 3.2 elaborates in some more detail on the ‘attitude’ concept in general, and ‘penal attitudes’ in particular. A number of different approaches to the definition and use of the concept of penal attitudes is briefly presented. Section 3.3 explores and justifies the arguments of why it is important to try to measure such attitudes. It is argued that the measurement of penal attitudes is essential for any study that is directly or indirectly concerned with the link between moral theory and practice. Section 3.4 discusses various strategies that can be used for measuring penal attitudes including some of the practical and methodological issues. Research experiences in the Netherlands and abroad are introduced both for illustrative purposes and to highlight the pros and cons of the different approaches (and should not be viewed as an exhaustive review of such research).

3.2 What is a penal attitude?

In the previous section penal attitudes have been broadly defined as attitudes towards the various goals and functions of punishment. Although such a definition introduces the object of the attitudes, the actual meaning of the concept attitude remains unexplained. Before elaborating further on penal attitudes and their measurement, a somewhat more detailed discussion of the attitude concept is therefore merited. Read more

Punishment And Purpose ~ Development Of A Measurement Instrument

4.1 Introduction

4.1 Introduction

In Chapter 3, the concept of penal attitude was examined in some detail. Furthermore, the point was made that, while research on psychological characteristics of magistrates is quite common in some other countries (e.g. United States, England, Canada, Germany), in the Netherlands this type of research seems to be a ‘blank spot’ (Snel, 1969). The few (predominantly qualitative) studies that were carried out have led to rather inconclusive results concerning magistrates’ penal attitudes. Furthermore, no systematic quantitative study on this topic has been carried out in the Netherlands thus far. We consider this to be a serious deficiency in criminological and psychological research on the Dutch magistrature.

The present chapter therefore focuses on the systematic process of developing a theoretically informed measurement model of penal attitudes. Section 4.2 discusses the measurement approach that we have adopted. However, our approach, like any other, is accompanied by a number of methodological and practical concerns. Each of these will be given due attention. Section 4.3 elaborates on the process of translating the relevant theoretical concepts into measurable variables (i.e., operationalisation) resulting in an initial version of the measurement instrument. In Section 4.4, the procedure and results of the first application of the instrument with Dutch law students (N=266) are discussed. Implications of this study for subsequent refining or revising the measurement instrument are then considered in Section 4.5. Section 4.6 describes the further steps in the development of the measurement instrument. The procedure and results of a second empirical study with Dutch law students (N=296) are reported. The results of this second study are compared to those of the first study thus allowing a measure of reliability (i.e. replicability) to be obtained. Finally, in Section 4.7, results of the second study with law students are used as the foundation for a basic (structural) model of penal attitudes. To further validate the measurement instrument, to confirm results of the studies with law students and to explore the structure of penal attitudes, this model will be tested in Chapter 6 using data collected from judges in Dutch criminal courts. The position we adopt is that the development of a theoretically integrated model of penal attitudes contributes to a better understanding of how moral legal theory becomes translated into practice by criminal justice officials. Read more

Punishment And Purpose ~ Intermezzo: Legal Context Of The Study

5.1 Introduction

5.1 Introduction

This chapter provides a concise outline of the legal context of the empirical studies that are reported in the following chapters. As such, it aims at describing only those aspects of the Dutch legal system and some of the practical issues involved that are considered to be the most relevant for our purposes.[i]

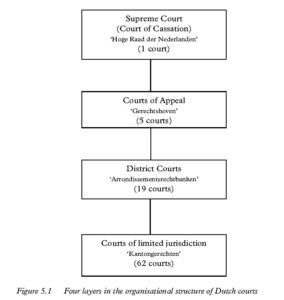

Section 5.2 first describes the organisational structure of Dutch criminal courts. The internal structure of the courts as well as hierarchy and competences amongst them are discussed. Subsequently, section 5.3 provides a brief outline of the Dutch sentencing system. A number of aspects of Dutch criminal procedure are described and the roles of the police, prosecutor, defence, probation service and judge(s) are discussed. Section 5.3 concludes with describing the main provisions in Dutch penal code (P.C.) pertaining to sanctions and sentencing. It will be demonstrated that Dutch penal code invests judges with wide discretionary powers in sentencing. Section 5.4 discusses these discretionary powers in more detail. The discretionary powers have prompted concerns for equality in sentencing. A number of (informal) aspects that influence and constrain judges’ discretion in sentencing are discussed as well as the main controversies that surround the issue of equality in sentencing.

5.2 Organisation of Dutch criminal courts[ii]

All cases in the Netherlands are tried by professional judges. Juries or layassessors are unknown. Candidate judges are appointed after completing six years of magistrate training (RAIO-training) subsequent to obtaining a law degree from a Dutch university. Aside from following a six year magistrate training, candidates with a law degree who have more than six years of experience in a legal profession may also be eligible for appointment. The organisational structure of the Dutch judiciary is regulated in the ‘Judicial Organisation Act’ (Wet op de Rechterlijke Organisatie). The court system is organised in four layers. Figure 5.1 shows the organisational structure of Dutch courts.[iii] Conventional Dutch terminology is printed in smaller typeface in Figure 5.1. The courts of limited jurisdiction form the lowest level in the hierarchy shown in Figure 5.1. In criminal cases these courts hear mostly misdemeanors (‘summary offences’).[iv] Cases in these courts are tried by judges sitting alone and are open for appeal to district courts by both the prosecution and the defence. The district courts will try the appeal cases de novo.

Felonies (serious cases) are tried by district courts.[v] The internal structure of a district court in criminal cases is such that a distinction can be made between judges sitting alone (unus iudex), panels of judges and judges of instruction (investigative judge). The most common types of judges sitting alone are judges handling juvenile cases (kinderrechter) and judges who hear cases in which the prosecution demands a penalty up to six months imprisonment. The latter type of judge bears the somewhat misleading name ‘police judge’ (politierechter), while they have nothing to do with the police. A special type of police judge is the economic police judge who hears cases involving the ‘Economic Offences Act’. Since by law (art. 369 C.C.P.) police judges cannot impose harsher sentences than six months of imprisonment, all more serious cases are brought before a chamber of the court which sits in panels of three judges. Read more

Punishment And Purpose ~ Penal Attitudes Among Dutch Magistrates

6.1 Introduction

6.1 Introduction

In previous sections a theoretically informed instrument and model for measuring penal attitudes has been developed. The instrument has first been applied to a sample of Dutch law students and then, after some revision, replicated with a second sample of law students. From both an empirical and theoretical point of view, analyses led to the conclusion that a six-dimensional structure is most appropriate and tenable for describing penal attitudes. Factor- and scale-analyses showed Deterrence, Incapacitation, Desert, Moral Balance, Rehabilitation and Restorative Justice to form internally consistent and readily interpretable dimensions and scales.

Results from the factor- and scale analyses on law students’ data have served as the foundation for a basic Structural Equation Model (SEM) of penal attitudes (the so-called baseline model). This baseline model was presented in Section 4.7. To further validate the measurement instrument and confirm results of the studies with law students, the baseline model is tested with data collected from judges in Dutch criminal courts. Such a sequence of analyses involving the use of data from different samples is believed to be effective for simplifying, refining and confirming a basic model (Bryant & Yarnold, 1995).

After testing the structural equation model we will proceed to construct corresponding summated rating scales. This will be carried out in a manner similar to that discussed in previous sections. The rating scales of penal attitudes will subsequently be used for more descriptive purposes. These rating scales will also re-appear in Chapter 8 where they will play an important role in analyses concerning magistrates’ views in concrete sentencing situations.

In Section 6.2 the process of data collection and some of the pitfalls involved are discussed. The organisation of Dutch criminal courts from which data were collected was described in the previous chapter. Section 6.3 describes response rates in some depth and Section 6.4 provides some background statistics of the sample of Dutch judges involved in this study. After these preparatory sections, the structural equation model is put to the test in Section 6.5. Subsequently definitive summated rating scales pertaining to the theoretical concepts are constructed and described in more detail in Sections 6.6 and 6.7. The chapter concludes with a concise discussion of the salience of penal attitudes among Dutch magistrates and their own perceptions of colleagues’ penal attitudes in Section 6.8.

6.2 Data collection

Data for our study have been collected from judges and justices in the criminal law divisions of the District Courts and the Courts of Appeal. Judges in Courts of Limited Jurisdiction were not of interest to this study since aside from civil cases, they hear mostly misdemeanours. Neither were justices in the Supreme Court of interest. These justices do not consider the facts of a case, but instead focus on issues of (formal) law. Therefore, only judges and justices from the 19 District Courts and the five Courts of appeal have been included in this study.[i] Read more

Punishment And Purpose ~ Punishment In Action: Development Of A Scenario Study

7.1 Introduction

7.1 Introduction

It has been argued that measurement of penal attitudes in a manner consistent with moral legal theory is a prerequisite for determining the relevance of moral theory in the actual practice of punishment. While Chapter 4 focused on developing and validating a theoretically integrated measurement instrument and model of penal attitudes, Chapter 6 involved the actual examination of Dutch judges’ attitudes towards the goals and functions of punishment. Results show that penal attitudes can be measured in a manner consistent with moral legal theory. The relevant (theoretical) concepts prove to be measurable and meaningful for Dutch judges. It has also been shown that the general structure of penal attitudes reveals a streamlined and pragmatic approach to punishment among Dutch judges. Although identifiably founded on the separate concepts drawn from moral theory, their approach appears to be dominated by two general perspectives: harsh treatment and social constructiveness. Since these were found to be uncorrelated, we expected particular characteristics of the offence and the offender to determine the balance between these perspectives in concrete cases.

Apart from measuring general penal attitudes and exploring the underlying structure, studying the relevance of moral legal theory for the practice of punishment involves yet another important aspect. A necessary further step is to explore the relevance and consistency of goals at sentencing (i.e. sentencing objectives) in concrete criminal cases. Judges’ decisions may be affected by the goals they pursue in general as well as in any particular sentence (Blumstein, Cohen, Martin, & Tonry, 1983). Thus having succesfully measured general penal attitudes, we now concentrate on preferred goals at sentencing in concrete cases. We believe that both types of findings (i.e., general penal attitudes and goals at sentencing) complement each other. Both types of data are necessary to acquire an overall and well-founded impression regarding the link between moral legal theory and the practice of punishment.

With this in mind, a scenario study was carried out. The study was designed to measure judges’ preferences for sentencing objectives in concrete cases and to determine the relevance and consistency of these preferences in the light of their sentencing decisions. Furthermore, judges’ preferences for sentencing objectives in concrete cases are compared to their general penal attitudes. Because the scenario study involves hypothetical criminal cases and requires judges to pass sentence, we refer to Chapter 5 for discussions on the Dutch sentencing system and Dutch judges’ discretionary powers in sentencing. In Section 7.2 the goals of the scenario study are discussed. Section 7.3 describes the method. In order to counterbalance unintentional and undesirable effects due to the method of research and manipulation of vignettes, a special experimental design of the scenario study proved necessary. Given its complexity, this design is discussed in Section 7.4. Section 7.5 describes the measures that were employed in the scenario study. The final section, Section 7.6, discusses the selection of suitable vignettes for the scenario study. Criteria and procedure for selecting, formulating and varying the scenarios are discussed in detail. Subsequently, in Chapter 8 results of the scenario study are presented. Read more

Punishment And Purpose ~ Punishment In Action: The Scenario Study

8.1 Introduction

8.1 Introduction

In the previous chapter the design and selection of vignettes for the scenario study were presented. This chapter reports on the results. Consistency and relevance of goals of punishment in the light of sentencing decisions are examined within and across vignettes. Due attention is given to differences in sentencing decisions within the framework of the criminal cases presented. Furthermore, the role of general penal attitudes in choosing preferred goals of punishment for the selected criminal cases is scrutinised.

The results will be presented in the following way. Following a description of data collection and sample characteristics in Section 8.2, undesirable framing effects of version are analysed in Section 8.3 using the full potential of the Graeco-Latin square design. In Section 8.4 judges’ preferences for goals of punishment are examined in detail within and across vignettes. The basic vignettes were designed to differ from each other in terms of pointers that are expected to evoke preferences for different sentencing goals (see Table 7.5 in Chapter 7). Given this manipulation, planned comparisons between the vignettes have been carried out to examine whether judges’ preferences for goals of punishment concur with our expectations. Subsequently, in Section 8.5, profiles of the basic vignettes in terms of sentencing decisions are presented. Within each criminal case variation in sentencing decisions is discussed. Once the goals of punishment and sentencing decisions have been examined independently, they are analysed simultaneously in Section 8.6. For the balanced vignette (A), the harsh treatment vignette (B), the rehabilitation vignette (C), and the reparation vignette (D), patterns of association between sentencing goals and sanctions are analysed and discussed. Finally, in Section 8.7, the relevance of judges’ general penal attitudes for choosing preferred goals of punishment in the presented criminal cases is examined and discussed.

8.2 Data collection and sample

At the end of the initial questionnaire examining judges’ general penal attitudes (see Chapter 6), respondents were asked whether they would be willing to co-operate in a follow-up study. If they agreed to do so, they were asked to write their name and address on a separate slip of paper. Of the 168 judges who responded in the penal attitude study of 1997, 106 (63%) stated their willingness to be involved in a follow-up study. This panel of 106 judges therefore formed the target group for the scenario study.

In order to minimise panel attrition due to any changes in respondents’ employment position or address, the courts’ registries were contacted in May 1998. The vast majority of the 106 judges still held the same position as they had one year earlier. In 1998, only 12 percent of the judges had either moved to another court or were working in another division within the same court (e.g. civil law division). The decision was made to include these judges.

In May 1998 a letter introducing the scenario study was sent to all 105 judges in the panel.[i] In this letter, judges were reminded of their co-operation in the first study and of their stated intention to co-operate in the follow-up study. Furthermore, the nature of the follow-up study was described and they were asked once more for their co-operation. At the end of May 1998 the questionnaires containing the vignettes as well as an accompanying letter were posted. Questionnaires were to be returned anonymously in pre-paid response envelopes. With two-week intervals, two reminders were sent restating the importance of response for external validity and again kindly requesting co-operation. Within two months, 84 judges had completed and returned the questionnaire, yielding a response rate of 80 percent. Since the scenario study only involved subjects who had previously stated their willingness to co-operate, such a high rate of response had been anticipated. These 84 respondents constitute 22 percent of the original population of 385 judges. Read more