Punishment And Purpose ~ Summary And Conclusions

The fact that a practice exists does not automatically imply that it is, or can be, consistently justified in its given form (even if this may have been the case in the past). The practice of punishment, it has been argued, is a morally problematic practice and therefore needs a consistent (moral) justification. The present study explored the justification of the Dutch practice of punishment from one particular perspective. The aim of the study was to determine whether or not a consistent legitimising framework, either founded in or derived from moral legal theory, underlies the institution and practice of legal punishment in the Netherlands.

The fact that a practice exists does not automatically imply that it is, or can be, consistently justified in its given form (even if this may have been the case in the past). The practice of punishment, it has been argued, is a morally problematic practice and therefore needs a consistent (moral) justification. The present study explored the justification of the Dutch practice of punishment from one particular perspective. The aim of the study was to determine whether or not a consistent legitimising framework, either founded in or derived from moral legal theory, underlies the institution and practice of legal punishment in the Netherlands.

In order to investigate the link between moral theory of punishment and the practice of punishment the first step was to explore whether concepts derived from moral legal theory have a meaning for criminal justice officials. Furthermore, it was necessary to explore how these concepts, as utilised by judges, interrelate. The gamut of perspectives concerning the justification and goals of punishment was narrowed down to three main categories: Retributivism, Utilitarianism and Restorative Justice. Retributivist theories are retrospective in orientation. The general justification for retributive punishment is found in a disturbed moral balance in society; a balance that was upset by a past criminal act. Infliction of suffering proportional to the harm done and the culpability of the offender (desert) is supposed to have an inherent moral value and to restore that balance.

Utilitarian theories are forward-looking. Legal punishment provides beneficial effects (utility) for the future that are supposed to outweigh the suffering inflicted on offenders. This utility may be achieved, through punishment, by individual and general deterrence, incapacitation, rehabilitation and resocialisation, and the affirmation of norms. Restorative justice emphasises the importance of conflict-resolution through the restitution of wrongs and losses by the offender. The victim of a crime and the harm suffered play a central role in restorative justice. The main objective is to repair or compensate the harm caused by the offence.

The central concepts of these three approaches to legal punishment were systematically operationalised as a pool of attitude statements to enable the measurement and modelling of penal attitudes. As a result of two extensive studies involving Dutch law students, this measurement instrument was refined, replicated, and validated. Based on the results of the second study with law students, a theoretically integrated (structural) model of penal attitudes was formulated. Following the two studies with law students, data were collected from judges in Dutch courts. Almost half of all judges working full-time in the criminal law divisions of the district courts and the courts of appeal cooperated with the study. Analyses revealed a number of interesting findings. Read more

Punishment And Purpose ~ References

Ajzen, I. (1988). Attitudes, personality and behavior. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Ajzen, I. (1988). Attitudes, personality and behavior. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Allport, G. W. (1935). Attitudes. In C. Murchison (Ed.), A handbook of social psychology (pp. 798–844). Worcester: Clark University Press.

Ashworth, A. (1992a). Deterrence. In A. von Hirsch & A. Ashworth (Eds.), Principled sentencing (pp. 53–61). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Ashworth, A. (1992b). Sentencing and criminal justice. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Bakker, I. (1996). Strafdoelen van rechters en Officieren van Justitie. Leiden: NISCALE.

Bazemore, G., & Feder, L. (1997). Judges in the punitive juvenile court: Organizational, career and ideological influences on sanctioning orientation. Justice Quarterly, 14, 87–114.

Bazemore, G., & Maloney, D. (1994). Rehabilitating community service: Toward restorative service sanctions in a balanced justice system. Federal Probation, 58, 24–35.

Beccaria, C. (1995). On crimes and punishments. In R. Bellamy (Ed.), On crimes and punishments and other writings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bentham, J. (1982). An introduction to the principles and morals of legislation. London: Menhuen & Co.

Bentler, P. M. (1986). Structural modelling and psychometrika: A historical perspective on growth and achievements. Psychometrica, 51, 35–51.

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological bulletin, 107, 238–246.

Bentler, P. M. (1992). EQS: Structural equations program manual. Los Angeles: BMDP Statistical Software.

Berger-Wiegerinck, M. F. M., Dooren-Berger, E. M. J., Nieuwenhuizen, W. A. P., Lever, A. B., de Vree, A. P., & Meijer, G. H. (Eds.). (1997). Gids voor de rechterlijke macht en het rechtswezen in het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden. Deventer: Noorduin.

Berghuis, A. C. (1992a). De harde en de zachte hand: Een statistische analyse van verschillen in sanctiebeleid. Trema, 84–93.

Berghuis, A. C. (1992b). Preventie. In C. Bouw, H. van de Bunt, & H. Franke (Eds.), Kernbegrippen in de criminologie (pp. 73–76). Arnhem: Gouda Quint.

Beyleveld, D. (1980). A bibliography on general deterrence research. Westmead: Saxon House.

Bianchi, H. (1986). Abolition: Assensus and sanctuary. In H. Bianchi & R. van Swaaningen (Eds.), Abolitionism: Towards a non-repressive approach to crime (pp. 113–126). Amsterdam: Free University Press.

Punishment And Purpose ~ Appendix 1~ 4

Appendix 1. Vignettes

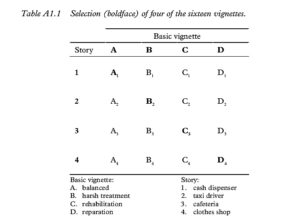

The boldface vignettes in Table A1.1 are included in this appendix

Table A1.1

A1. Robbery at a cash dispenser: balanced

Late in the evening, a man is taking money from a cash dispenser in the hall of a bank when he is suddenly grabbed and punched in the face. He sees before him a man with a black nylon stocking on his head and a gun in his hand. The offender tells the victim to take NLG 1,000 from the cash dispenser for him, otherwise he will shoot. The victim panics, and starts to shout and hit out wildly. This causes the offender, Johannes Cornelis Vrugink, such consternation that he takes from the machine the NLG 150 that the victim had already requested and runs away. In all the commotion he forgets to remove the nylon stocking from his head.

One street away, two police officers on their beat stop Vrugink, who is still wearing the stocking on his head. When Vrugink tries to run away, the officers grab hold of him and then search him. In his pocket the officers find a toy gun, which has been painted black, and NLG 150. Vrugink is taken back to the station and questioned. At first Vrugink denies any wrongdoing. Soon after the arrest, however, the victim arrives to report the offence. When Vrugink is confronted with the information provided by the victim, he finally admits to the offence. The toy gun, the nylon stocking and the NLG 150 are seized. Vrugink is kept in custody for another three days and then released.

The victim is a 40-year-old man. He is married with two children. Immediately after the offence he went to the hospital’s casualty ward. His nose was found to be broken and he received treatment. His glasses, worth NLG 600, were destroyed by the punch. The victim says that being threatened by the (toy) gun has traumatised him. He was on sick leave for two months after the offence. Now he is still fearful, particularly out of doors. He has trouble sleeping and finds it very difficult to concentrate at work. The victim is not party to the action, but is present at the trial.

Nineteen-year-old Johannes Cornelis Vrugink is unmarried and at the time of the trial has been living with his girlfriend, also 19 years old, for several months. Vrugink previously lived from the age of 16 with his uncle, after running away from home because of continuing problems with his stepfather. After primary school, Vrugink attended but did not complete the LTS (junior technical school). He has had a number of jobs through an employment agency but kept leaving them because he found the work too dull, had difficulty getting up on time in the morning, and usually argued with his employers. Vrugink has trouble dealing with conflict situations. He says that out of boredom he ‘smokes a lot of dope’ and gambles regularly. These activities cost a great deal of money. There are no further indications of addiction to hard drugs. Vrugink committed the offence because of a chronic lack of funds and in order to have money to impress his friends. Vrugink was unemployed at the time of the offence. He receives income support and is following a professional driving course. He is in the process of setting up his own transport business, with the help of his employment agency.

Vrugink is present at the trial. When allowed a final word, he says that he wants to dedicate himself fully to making a success of his business and keeping on the straight and narrow so that he can lead a normal life with his girlfriend. He tells the victim that he deeply regrets his acts and wants to change his lifestyle.

The judicial documentation shows that when Vrugink was 18 years old he received a magistrate’s fine of NLG 200 for assault. At 17 years old, Vrugink spent two months in a youth custody centre for robbery. He has also been involved with the law in connection with vandalism and shoplifting. No sentences were passed in these cases. Read more

Alison Flood ~ The 20 Most Influential Academic Books Of All Time: No Spoilers

The Guardian ~ Open Culture. Sometimes I’ll meet someone who mentions having written a book, and who then adds, “… well, an academic book, anyway,” as if that didn’t really count. True, academic books don’t tend to debut at the heights of the bestseller lists amid all the eating, praying, and loving, but sometimes lightning strikes; sometimes the subject of the author’s research happens to align with what the public believes they need to know. Other times, academic books succeed at a slower burn, and it takes readers generations to come around to the insights contained in them — a less favorable royalty situation for the long-dead writer, but at least they can take some satisfaction in the possibility.

The Guardian ~ Open Culture. Sometimes I’ll meet someone who mentions having written a book, and who then adds, “… well, an academic book, anyway,” as if that didn’t really count. True, academic books don’t tend to debut at the heights of the bestseller lists amid all the eating, praying, and loving, but sometimes lightning strikes; sometimes the subject of the author’s research happens to align with what the public believes they need to know. Other times, academic books succeed at a slower burn, and it takes readers generations to come around to the insights contained in them — a less favorable royalty situation for the long-dead writer, but at least they can take some satisfaction in the possibility.

The shortlist of these most important academic books of all time runs as follows (and you can read many of them free by following the links from our meta list of Free eBooks):

Amongst others:

Stephen Hawking ~ A Brief History of Time

Immanuel Kant ~ Critique of Pure Reason

Germaine Greer ~ The Female Eunuch

Niccolò Machiavelli ~ The Prince

Adam Smith ~ The Wealth of Nations

http://www.openculture.com/the-20-most-influential-academic-books

Combatting Climate Change Requires A Transition To New Economic Values: An Interview With Graciela Chichilnisky

Climate change represents the greatest threat facing humankind. Yet, not only is very little being done to combat the climate change threat, but there are still vocal climate change deniers around us, some of whom are even running for the presidency of the United States. Moreover, there seems to be confusion about the most effective ways to combat climate change. The latest effort by global leaders to address the problem of climate change, as reflected in the Paris Agreement of late 2015, falls short of implementing the necessary steps to save the planet.

Climate change represents the greatest threat facing humankind. Yet, not only is very little being done to combat the climate change threat, but there are still vocal climate change deniers around us, some of whom are even running for the presidency of the United States. Moreover, there seems to be confusion about the most effective ways to combat climate change. The latest effort by global leaders to address the problem of climate change, as reflected in the Paris Agreement of late 2015, falls short of implementing the necessary steps to save the planet.

But this begs the question. What are the necessary steps that need to be taken to prevent a catastrophic climate change scenario? In this exclusive interview for Rozenberg Quarterly, world renowned economist and climate change authority Graciela Chichilnisky discusses the nature of the problem of climate change, highlights what is at stake, and argues cogently what should be done to save the planet.

Professor Chichilnisky, it is widely known that climate change can be caused by both natural variations and human activity. Is the climate change being observed today due to natural variations or are its causes to be found in human activities and greenhouse gas emissions?

Scientists all over the world are in agreement that the climate variations we observe today are due to a global change in climate, and that increased greenhouse gases in the atmosphere from human activity, particularly the burning of fossil fuels since 1945, are responsible for climate change. This is not a gentle warming trend, it is the melting of the North and the South poles, and a confirmed rising level of the oceans worldwide that will engulf large areas of the planet, and include 43 island nations states.

In the United States, virtually all leading Republican figures, including Donald Trump, who has already wrapped up the Republican nomination, argue that climate change is based in pseudo-science. What’s going in here? Are Republicans so out of touch with reality, or are they simply interested in protecting vested interests in the fossil fuel economy?

The Republican party is conservative by nature and resists change, even the acknowledgment of the need for change. This is a natural human response. Denial is known to be the first psychological response to a traumatic event, and climate change is potentially catastrophic. Denial is a natural first response and can take the form of denouncing climate science as pseudo-science. However understandable the reaction may be, we cannot remain mired in the first response to a traumatic event, and need action. It is now possible to take action as there are technologies that can remove the carbon that is already in the atmosphere in an affordable way, and this is needed now to avert catastrophic climate change. But it requires moving from the stages of denial and anger to the stage of acceptance. Then we can take action and create global policy as needed.

However, there are some scientists and former astronauts who claim that NASA’s studies of climate change, for example, are based in highly complex models which have proven highly inadequate in the last. Any comments on this?

Indeed, climate models are recent scientific developments and they are complex. This is true. Nobody can predict the weather exactly for example. But the scientific evidence for the overall climate change trend is now overwhelming accepted by most scientific bodies, including the IPCC which is the UN scientific body consisting of thousands of scientists from all over the world, and nobody debates that. Read more

Wouter van Veenendaal ~ Politics And Democracy In Microstates. A Comparative Analysis Of The Effects Of Size On Contestation And Inclusiveness

What this Dissertation is About

What this Dissertation is About

According to several recent publications, small states or microstates are comparatively more likely to have democratic systems of government than larger states (Diamond and Tsalik 1999; Anckar 2002b; Srebrnik 2004). Based on the data of aggregate indices of democracy such as Freedom House, these large-N quantitative analyses have disclosed a statistically significant negative correlation between population size and democracy. Although a satisfactory explanation of this pattern has not yet been found, the argument that a limited population size fosters good governance, republicanism, and democracy was already formulated by the ancient Greek philosophers, and is therefore one of the most ancient debates in political science. The finding that microstates from around the globe are exceptionally likely to develop and maintain democratic systems of government therefore appears to validate centuries-old theories about the political consequences of size. In addition, not only has the average population size of countries continuously been decreasing since the late 19th century (Lake and O’Mahony 2004), but more and more states have initiated programs of decentralization and devolution of powers and competences to smaller, sub-national units. This unmistakable trend towards smaller polities and administrations is buttressed by academic publications that emphasize the virtues and advantages of smallness (cf. Schumacher 1973; Katzenstein 1985; Weldon 2006).

Full text (PDF): https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/bitstream/Veenendaal.pdf