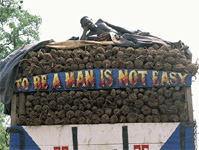

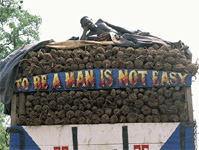

To Be A Man Is Not Easy ~ Education, Solidarity And Being Able To Say No. Interview With Matthew Essieh

Matt Essieh is my name, born in Sampa which is a village on the border with Ivory Coast. I loved school but had to stop at age twelve after completing middle school. My parents were very poor, even so that I had to live as an altar boy at the Catholic mission. My parent’s house was literally too small for all their children and you know that we Africans can improvise! So I grew up at the mission. After middle school I went across the border into Ivory Coast and stayed with an aunt. It was my own idea and the only way I knew to find money to further my education for which I have a passion. Yes so my plan was to do odd jobs and so raise enough money to support myself through secondary school. I decided on moving over the border into another country because in those days the economy over there was better. It was for example possible to earn money delivering loads at the local market with your wheel barrel and I also sold ice-cream with one of these bicycles with a cold box up front. I was willing to do everything. I cleaned tables in one of the hotels and many other ‘by-day’ jobs, whatever I could find.

Matt Essieh is my name, born in Sampa which is a village on the border with Ivory Coast. I loved school but had to stop at age twelve after completing middle school. My parents were very poor, even so that I had to live as an altar boy at the Catholic mission. My parent’s house was literally too small for all their children and you know that we Africans can improvise! So I grew up at the mission. After middle school I went across the border into Ivory Coast and stayed with an aunt. It was my own idea and the only way I knew to find money to further my education for which I have a passion. Yes so my plan was to do odd jobs and so raise enough money to support myself through secondary school. I decided on moving over the border into another country because in those days the economy over there was better. It was for example possible to earn money delivering loads at the local market with your wheel barrel and I also sold ice-cream with one of these bicycles with a cold box up front. I was willing to do everything. I cleaned tables in one of the hotels and many other ‘by-day’ jobs, whatever I could find.

This hotel had a restaurant where many of the Peace Corps volunteers used to come and have a drink after their work. The French language is hard for the Americans and I spoke English with them. Two Peace Corps volunteers took a special interest in me. They were maybe 21 years old and I was then 15. They really wanted to help me go through high school. So with the money I earned over these three years in Ivory Coast, and with their help, I found admission at secondary school in Brong Ahafo in Ghana. I was a little tiny skinny kid at that time so I looked as young as the other students. These volunteers helped me so much because they paid most of the tuition fees. I almost finished secondary school but during my last year one of the volunteers died. She had leukemia and died in Washington DC. I heard later that before this girl died she asked her parents to please look after ‘the boy in Ghana’. They then took such an interest in me that they helped me go to college in the States. I went to Oregon, Southern State Oregon University. When I left Ghana and entered college in The States I was probably 20 or 21.

Oregon is beautiful and quiet. It was the perfect place for me coming from a small rural town in Ghana. The atmosphere is nice that’s why I was specially grateful to be able to attend college over there on the West Coast. I graduated in computer business and then also got a Masters Degree in business studies.

Of course when you grow up here in Ghana you never forget your family. You feel strongly that you need to help your own country. So I studied hard and worked hard and was quite successful in both. I sought to get jobs which enabled me to best help my family in Ghana, like other Ghanaians do to their family. Read more

To Be A Man Is Not Easy ~ Caught Between Two Worlds. Interview With Samuel Oteng

Samuel Oteng is the name. In 1987 I went to Austria. After a few years I got the papers ready and my wife came to join me where I live, a small town called Graz. Our children were born in Austria. Two, a boy and a girl, both go to school. As a family we are settled in Graz and have no intention to move away, moving now would hurt my children’s education and their social life with their friends. My son Godfred, who is twelve, attends what they call the ‘Gymnasium’ over there and my girl Precious, who is eight, is at the primary school. Precious says she likes where she lives and she has a gang of white girlfriends with whom she feels free and happy. She also loves nature. Our part of the country is beautiful and she does not want to move to a big city. I am the same in that way, I love the natural beauty of where we live. No, we won’t move.

Samuel Oteng is the name. In 1987 I went to Austria. After a few years I got the papers ready and my wife came to join me where I live, a small town called Graz. Our children were born in Austria. Two, a boy and a girl, both go to school. As a family we are settled in Graz and have no intention to move away, moving now would hurt my children’s education and their social life with their friends. My son Godfred, who is twelve, attends what they call the ‘Gymnasium’ over there and my girl Precious, who is eight, is at the primary school. Precious says she likes where she lives and she has a gang of white girlfriends with whom she feels free and happy. She also loves nature. Our part of the country is beautiful and she does not want to move to a big city. I am the same in that way, I love the natural beauty of where we live. No, we won’t move.

Also, after all, I have my work and I’m much involved in the community. Specially our church. Apart from what I said about the children and their education I have been working in that factory all my years and I do not want to lose the benefits and start all over again in London. But otherwise, yes, sometimes we dream of moving to England!

The problem is that most of our Ghanaian friends move away from Austria to the UK. As soon as they have their Austrian passport you see them going, one by one. All the time we lose more friends. It is true that living circumstances for Africans are much better in England as compared to, especially, Austria. In Austria black people are isolated because Austrians stay away from us. It makes life difficult that way. People in England are used to Africans and all kind of other nationalities and they are friendly. Of course the language too plays a role. That’s why my people leave.

As I said I am not going to go to England like my friends. They challenge me: ‘you are an Austrian citizen and so you can freely move to anywhere in Europe’. But no, we stay in Graz.

What I don’t like is being the eternal outsider. The work also is hard. I get up early come back late, hardly see my children, my wife works too, so hardly see her at all. And now we face this exodus of Ghanaian friends leaving for Britain. Others are talking about it, some are packing. We stay where we are but it is sad to stay back here alone.

Do you think I could get a job as a bus-driver in Austria? Or any job where you get in touch with other people? No. Not in Austria and especially not in Graz where we live. I tell you, in the beginning people were afraid of me. When I would board a bus for example all other passengers would look at me. I sit in the front, they all move to the back. If I sit at the back they quietly stay in the front of the bus. All the same that was eighteen years ago and things are changing. When I came I was the only African in town and people would always look at me and sometimes point: ‘Schwartze’, which means ‘black-man’ and I would just feel bad. Anyway I was lucky because I got a job. I still have that same job after more than 15 years. I work in a factory and there at my workplace I feel at home and they like and respect me there. Read more

To Be A Man Is Not Easy ~ The Conference Participant. Interview With Osei Takyi

I was invited to a conference and that is how I arrived one early morning at the airport of Frankfort. Forty three years old, first time overseas, big airport and sleepless night. I tried not to show my anxiety and then I saw my friends Rudi and Susan and they hugged me ‘Welcome to Germany’. At once I felt good. But also cold and strange. I saw no leaves on the trees. They said you are lucky it is spring now, look at the first green leaves. But whereever I looked the trees looked bare and dead to me. I was in a dream. We drove to their house and then the sun came through, I brought it with me they said! After dinner it was still light outside.

I was invited to a conference and that is how I arrived one early morning at the airport of Frankfort. Forty three years old, first time overseas, big airport and sleepless night. I tried not to show my anxiety and then I saw my friends Rudi and Susan and they hugged me ‘Welcome to Germany’. At once I felt good. But also cold and strange. I saw no leaves on the trees. They said you are lucky it is spring now, look at the first green leaves. But whereever I looked the trees looked bare and dead to me. I was in a dream. We drove to their house and then the sun came through, I brought it with me they said! After dinner it was still light outside.

Here in Ghana sun-up 6, sun-down 6, but not over there. I was exhausted and wanted to sleep but sleep would not come because of the light and all the strangeness.

Next morning was Sunday and we went to Church. It was a huge building so I thought there will be thousands of people worshipping there but I saw only twenty-five or so grey haired people. Then we saw another church which they had turned it into a restaurant which I did not want to believe. But I saw it.

In the afternoon we drove to a restaurant with all the participants of the conference and we had pizza. My first time pizza and I had to chose between mushroom, fish, spinach, I don’t know how many choices and so finally we tasted them all and overate! That I enjoyed and that night I slept.

Next day the program started with a visit to a special school for mentally handicapped children. I was amazed to see all their equipment. The atmosphere was good, not much discipline like here in Ghana, no, a lot of liberty for the kids, I even saw some children smoking, the bigger ones, they would go out and have a smoke. In Ghana, never!

They were friendly and asked me so many questions that I was amazed how very free they were and how much they wanted to know about Ghana. They had made paintings and we were to unveil them. The week was wonderful, every day another program, discussions in small groups about development, a forum on globalization, more visits to schools and mostly meeting each other and the German people and looking around seeing the town. We were catching the European spirit. Their town was so serene and quiet, not at all like Ghana where we make noise playing our speakers and so on. I really liked that quiet, it marveled me. Even the train is quiet, straight and swift and well oiled. Two different worlds which I kept comparing. Hospitality is higher in Ghana but the noise level too. In Germany at times they are friendly and at times they just walk away from you when you ask a question. Sunday we closed the conference with a party and we all sang and danced and had fun. Then we left. I took the train to Austria to visit my in-laws there. The next ten days were like a visit to another Ghana, the Ghanaian society in Graz in Austria. The train ride was a new experience. It was cold in the train and at each station there was police who asked me for my passport and ticket. They take your passport and after some time, fifteen minutes or so, bring it back. I understand they look for illegal immigrants but I became very tired with it for I wanted to sleep and at least six times they woke me up because of papers. Then we reached Vienna and it was early morning of the next day. I asked for the train to Graz. The police came with dogs to inspect my bags and they took twenty minutes searching everything, even flipped my bible to see if nothing was hidden in it. Then I took a taxi to another station and found the train to Graz. I admired the landscape, high mountains capped with snow, so beautiful that all the way to Graz I made pictures instead of catching up with sleep. Three hours later I was in Graz and called Samuel’s wife to pick me up. She had to work so in a rush she showed me the kitchen and was gone and I was alone! I slept at once and in the evening I heard Samuel open the door and heaven broke loose! We made so much happy noises that even the neighbors came out to see if all was well. We are happy, we said. I was so happy to be united with Ghanaians again and on top of it they are my real family! While the parents worked their boy showed me all of Graz. He is twelve. He is the one who had time so after school he showed his town to his uncle! I was there for ten days and visited all the Ghanaians from Nkoranza who I all know well. Lunch, dinner, talking, dancing, music, catching up! It was small Nkoranza! In Graz we went to church with the Ghanaians, Samuel’s church, and that was great, that was real worship, a full church like here in Ghana! Like being home. The church is underground so the noise does not disturb other people. Read more

Bamanya: Un Livre Dans La Forêt

Si tu tires une croix diagonale sur une carte moderne du monde, tu verras que Mbandaka se trouve au centre. Stanley érigeait ici en 1883, un “outpost of progress” sous le nom d“Equator Station”. Maintenant, Mbandaka (Coquilhatville jusqu’en 1966) est une des plus grandes villes du Congo, avec entre l00.000 et 150.000 habitants. Le bourg à la rive de cette grande rivière, le Congo, est pauvre; il y a peu ou pas d’industrie.

Dans le centre, les traces de l’époque coloniale sont encore visibles. Le long des larges rues, on trouve les ruines, ou les restes des pillages successifs, des jolies maisons au style colonial.

Plus de quarante ans de déclin n’ont laissé rien d’entier.

La ville est la capitale de la Province de l’Equateur. Le territoire, deux, trois fois les Pays-Bas, évoque dans le reste du Congo un sentiment compatissant: c’est le pays des chasseurs et des pêcheurs.

Dix kilomètres de Mbandaka se trouve le village de la mission de Bamanya. La piste de sable qui y mène est caractérisée par les légendaires nids de poules qui mettent homme et véhicule à dure épreuve.

Le premier matin de mon séjour, je suis éveillé par des chansons. Une centaine de voix jubilantes d’enfants fait fonction de réveil. Ce sont les enfants de l’école de la Mission qui en guise de gymnastique marchent en galop vers la bourgade voisine. Il est sept heures et demi. Je prends une douche froide, et pendant que je m’habille, la sueur gicle de ma tête.

Les cent cinquante abonnées des Annales Aequatoria doivent patienter: Les plaques d’aluminium pour l’imprimerie à Kinshasa se trouvent depuis des mois à Matadi, la ville portuaire du Congo et attendent le dédouanement. C’est un des multiples problèmes contre lesquelles on a à se battre dans ce pays quand on veut entreprendre quelques chose. “C’est l’Afrique” est l’argument sans réplique.

L’annuaire est publié par le Centre Aequataria, Centre de recherches Culturelles Africanistes. Le Centre possède une bibliothèque avec environ 8.000 livres et 300 titres de périodiques. Des archives linguistiques et historiques (locales) complètent cette documentation spécialisée. Read more

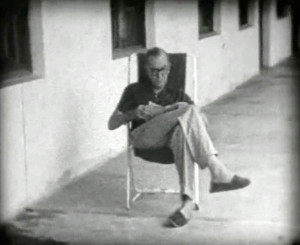

Tiny Bouts Of Contentment. Rare Film Footage Of Graham Greene In The Belgian Congo, March 1959

My purpose in this contribution is to present and contextualize the only film footage ever recorded of the novelist Graham Greene (1904-1991) in the Belgian Congo in 1959. The footage was filmed with an 8mm camera, which did not record sound. It belongs to Mrs. Édith Lechat (née Dasnoy;1932-) and her husband, the leprosy specialist Doctor (later Professor) Michel Lechat (1927-2014).

From 1953 through 1960, Dr. Lechat was head of the leper hospital and colony of Iyonda, a village and mission station some 15 kms south of the city of Coquilhatville (now, Mbandaka) in central-western Congo. Greene stayed a number of weeks in Iyonda and other mission stations in the region in search of inspiration, a setting, and material for a new novel. The novel, A Burnt-Out Case, appeared in 1960, and was dedicated to Dr. Lechat. Greene occupied a room in the house of the missionary fathers in Iyonda, but spent long parts of his days with the doctor and his family. The film reached me through the hands of Édith Lechat, who had it transposed to a DVD-playable format, and via my friend Hendrik (a.k.a., “Henri” or “Rik”) Vanderslaghmolen (1921-), who was a missionary in the region at the time. As he was one of the only Belgian missionaries there with some knowledge of English, he often accompanied Graham Greene during his trips from one mission station to another. Rik Vanderslaghmolen and the Lechats are still close friends today.

Much of the information I offer below stems from conversations I had with both Rik Vanderslaghmolen and Édith Lechat in July and August 2013. Regrettably, Dr. Michel Lechat’s poor health condition did not allow me to probe his memory, but an interview he gave for the Brussels-based weekly The Bulletin on the occasion of Greene’s death in 1991 is available (Lechat 1991), as well as a closely similar talk he gave at the 2006 Graham Greene Festival in Berkhamsted, published in the London Review of Books in August 2007 (Lechat 2007). Édith Lechat has given me the kind permission to share the film with the readership of Rozenberg Quarterly and to add the necessary contextual information on both the historical situation and the contents of the film.

From The Web – Enduring Voices

Nearly 80 percent of the world’s population speaks only one percent of its languages. When the last speaker of a language dies, the world loses the knowledge that was contained in that language. The goal of the Enduring Voices Project is to document endangered languages and prevent language extinction by identifying the most crucial areas where languages are endangered and embarking on expeditions to:

Understand the geographic dimensions of language distribution

Determine how linguistic diversity is linked to biodiversity

Bring wide attention to the issue of language loss

When invited, the Enduring Voices Project assists indigenous communities in their efforts to revitalize and maintain their threatened languages.

The Language Hotspots model was conceived and developed by Greg Anderson and David Harrison at the Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages. It is a new way to view the distribution of global linguistic diversity, to assess the threat of language extinction, and to prioritize research. Hotspots are those regions of the world having the greatest linguistic diversity, the greatest language endangerment, and the least-studied languages.

Read more: http://travel.nationalgeographic.com/travel/enduring-voices/