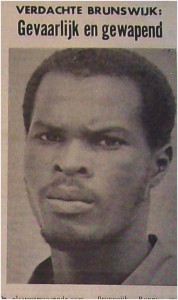

The making of Ronnie Brunswijk in Nederlandse media

‘De binnenlandse oorlog in Suriname was als oorlogsverslaggever een van mijn mooiste reizen. Het was een bijna zwart-wit verhouding. The good guy tegen de bad guy’, zei Arnold Karskens, doorgewinterd oorlogsjournalist, tijdens de presentatie van zijn boek Rebellen met een reden eind oktober 2009 tegen de Wereldomroep. In die Binnenlandse Oorlog (1986-1992) – zoals de strijd tussen Ronnie Brunswijk en voormalig bevelhebber van het Nationaal Leger Desi Bouterse genoemd wordt – was Bouterse in de ogen van Karskens the bad guy. ‘Want Desi Bouterse was natuurlijk verantwoordelijk voor veel doden in Suriname.’ De strijd van Brunswijk was wat Karskens betreft ‘een rechtmatige strijd tegen de dictatuur’ [i] En vóór terugkeer van de democratie. Niet iedereen zal het met Karskens eens zijn geweest. Sommigen – ook buiten de kring van Bouterse-getrouwen – menen dat de Binnenlandse Oorlog het democratiseringsproces dat kort daarvoor in gang was gezet, juist verstoorde![ii]

Met zijn uitspraak bevestigde Karskens het beeld dat er bestaat van partijdigheid van het Nederlandse journaille bij de Binnenlandse Oorlog. Tijdens de gesprekken die ik voerde voor mijn boek Suriname na de Binnenlandse Oorlog kreeg ik het verwijt vaak te horen. Zo wilde ex-commandant Henk Roy Matui – Mato – wel praten over de reden waarom de Tucayana Amazones zich mengden in de strijd tussen Bouterse en Brunswijk, maar niet voordat hij zijn hart had gelucht. Hij vond: de Nederlandse media maakten Brunswijk ‘groter’ dan hij was (De Vries 2005:133).

When Congo Wants To Go To School – Part III – Acti Cesa

A few years ago Catherine Coquery-Vidrovitch wrote about the results of the educational system in the Belgian Congo that “(This) in depth work concerning mentalities was started to be felt from 1945. [i] We have tried to approach the issue of the effects of the missionary education from two angles. On the one hand, on the basis of the written testimonies that can be found, from which it is apparent how the Congolese reacted, how they acted and what they thought about that education. Publications in which the opinion of the Congolese pupils and former pupils can be found were sought as contemporary sources. Concrete, extensive and detailed research was carried out into one of those publications, La Voix du Congolais. On the other hand, it is possible to make use of memories. These are preferably the memories of the people themselves. A number of interviews with the Congolese helped complement the very sparse literature available in this regard.

A few years ago Catherine Coquery-Vidrovitch wrote about the results of the educational system in the Belgian Congo that “(This) in depth work concerning mentalities was started to be felt from 1945. [i] We have tried to approach the issue of the effects of the missionary education from two angles. On the one hand, on the basis of the written testimonies that can be found, from which it is apparent how the Congolese reacted, how they acted and what they thought about that education. Publications in which the opinion of the Congolese pupils and former pupils can be found were sought as contemporary sources. Concrete, extensive and detailed research was carried out into one of those publications, La Voix du Congolais. On the other hand, it is possible to make use of memories. These are preferably the memories of the people themselves. A number of interviews with the Congolese helped complement the very sparse literature available in this regard.

When considering this theme, the original boundaries of the research subject were slightly deviated from. The research subject was deviated from as regards the material, as the

interviews are situated both within but also partly outside the mission area of the MSC. The existing research results that were consulted and used also relate to areas outside the Tshuapa region. Moreover, the research subject was deviated from with regard to content due to the conclusion that research into the effects of education is inextricably connected to the “memory” of the colonial period. Consequently, it seemed interesting to us to take the memories of former pupils into account. That has the undeniable advantage that the image drawn may be confronted to a certain extent with the memories of the Congolese.

In the previous four chapters, written material was primarily collected that spoke about the events that took place in and around the school in the mission area of the MSC. The image created as a result is perhaps still not very clear but the outlines may be discerned. Naturally coloured by all the information I collected myself as a researcher and undoubtedly also coloured by the information I did not collect, I did not think it very useful to consider all that material again in a conclusive chapter and to attempt to distil a summarising image from that.

I will therefore restrict my conclusion to an indication of the image drawn and the formulation of a number of considerations regarding the way in which this past is handled and the role this research may hopefully play in it.

NOTE:

[i] Tshimanga, C. (2001). Jeunesse, formation et société au Congo/Kinshasa 1890-1960 . Paris: L’Harmattan. p. 5 (préface). [original quotation in French]

When Congo Wants To Go To School – The Short Term: Reactions

Effects on the colonists: initiation of an African science of education?

Effects on the colonists: initiation of an African science of education?

In 1957 Albert Gille, Director of Education at the Ministry for Colonies, wrote that the biggest problem of education at that time remained the lack of well-trained teachers. He claimed that the quality of the teaching staff remained low and that there would be no improvement over the next few years.[i] There was not much opportunity to climb the social ladder. There were very few signs that the educational principles had changed under the impulse of Buisserets policy, which indeed ‘broke open’ the educational system. In fact, education in the Congo then became ‘metropolised’,[ii] but the changes in the curriculum were not accompanied by a significantly different composition of the body of teachers. The impact of the changes was quantitatively too limited to be able to bring about a general change in the short term. Until after independence, education would still remain almost completely in the hands of the mission congregations.

The early Congolese universities did produce some scientific research on education, but this research did not break out of the familiar straightjacket either. At the University of Lovanium research results and opinions in the field of education were published in the Revue pédagogique, which has already been mentioned. At the Official University Paul Georis was particularly active in the area of educationalism, but the results of his investigations only appeared after independence.[iii] Georis was the head of a so-called “interracial” high school in Stanleyville for four years and studied the possibilities of developing educational theory adapted to African circumstances there. His colleagues did the same in Luluaburg and Lodja. The most important elements that came to the fore in the research on such new educational theories, which he published in 1962 (but had written before independence), were the community life of the Congolese, the uniqueness of Congolese culture and respect for foreign cultures. In addition, the importance of an improvement of the level of education was also emphasised. Georis also referred to the splitting of education into mass- and elite-education. That it was necessary to point out, even in this publication, which was written in rather ‘progressive’ milieus, that “the qualitative equality of the intelligence of the Black and the White can be proven” is telling of the zeitgeist. In that respect the author also argued for a uniformity and equivalence in the primary education system for all levels of the population.

However, there were a number of obstacles in the way of the development towards a balanced educational system. Besides the vast size of the country and – here too – the poor quality of the teaching body, Georis mentioned the Congolese attachment to their ancestral traditions and the influence of magic as primary elements. Generally speaking, he seemed to argue for blending the traditional African values with imported Western ideas, which naturally did not prevent him from arguing within a progressive or developmental paradigm. Despite all his good intentions, he regularly remained bogged down in the model of ‘civilisation versus primitivism’. The “black”, he concluded in his study, could free himself from his neuroses and his complexes. Apparently that was still necessary.

On the other hand, an 1958 editorial contribution in the Revue Pédagogique about the “programmes métropolitains” and the adaptation of education, stated that: “In the Congo, we have for a long time attempted clumsy and timid adaptations, which proved inoperative. Now we are turning away from this path and are increasingly adopting the metropolitan curricula from Belgium, following the example of France, which has applied the French curricula for a long time.” Consequently, at that time, there was some hard thinking going on in both university milieus concerning the direction of education. In both cases questions were being asked aloud about the manner in which things had been done in the past. It is not illogical that in university circles at that time more discerning and detailed analyses were being made. There was a great deal of political activism at that time: in 1956 the manifestos of Conscience Africaine and the ABAKO had already been published and in 1958 the MNC of Lumumba and Ileo was formed; local council elections were also organised in 1958. The predominant attitude, also applicable to the educationalists, was still very expectant, cautious and doubtful.[iv] Even the contribution mentioned above, after initially pleading pro métropolisation, stated that it was very unclear what the Africans really wanted. They longed for Western education, to be able to get Western diplomas, because that was the only way to be recognised as an equal. But at the same time they also wanted something else and the next step would then have to be recovering their own cultural identity. The periodical’s attitude was summed up well in the last sentence of the contribution: “These are the general and imprecise assertions that must nevertheless be taken into account.”

Effects on the colonised: the needle in the haystack

2.1. At a university level

If we want to judge the effects of education, we must necessarily search for the voices of the people involved and those are primarily the Congolese. In the case of the universities and the science of education itself, this voice did not ring out very loudly. The reasons for this are not hard to find: it was too late and there were too few of them. At the University of Lovanium the first seven Congolese students graduated in June 1955 from the first year of a bachelor in Educational Science. Of these only two graduated three years later in June 1958 with a master’s (these were two priests, Michel Karikunzura and Ildephonse Kamiya).[v] In Elisabethville, where the ‘Official’ University operated from 1956, a ‘School for Educational Sciences’ was set up from the beginning. During the academic year 1957-1958 five African students were enrolled in the first year of the bachelor’s degree at the school (there were a total of 17 African students enrolled at the University at that time). In Lovanium there were 110 African students, of which 18 studied educational sciences.[vi] Read more

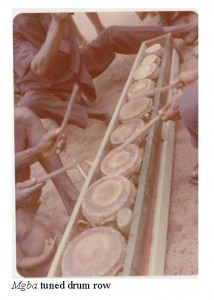

The Igbo Concept Of Mother Musicianship

Music is a ‘woman’, and intuitive creative management of life is more of a feminine attribute. Music is a communion, a social communion that nourishes spirituality, and manages socialisation during public events. These are some of the philosophical and concrete rationalizations that guided the indigenous categorization of an extraordinary performance-composer irrespective of gender or age as a mother musician as per indigenous terminological evidence in Africa. A composer gestates and gives birth to sonic phenomena.

Music is a ‘woman’, and intuitive creative management of life is more of a feminine attribute. Music is a communion, a social communion that nourishes spirituality, and manages socialisation during public events. These are some of the philosophical and concrete rationalizations that guided the indigenous categorization of an extraordinary performance-composer irrespective of gender or age as a mother musician as per indigenous terminological evidence in Africa. A composer gestates and gives birth to sonic phenomena.

Musical meaning has been discussed from the indigenous perspective as being based on the factors of musical sense, psychical tolerance and musical intention. The practice of performance-composition has also been identified as processing the realisation and approval of musical meaning as per context. Central to the philosophy of musical meaning as a society’s conceptualization of creative genius are the creative personalities who interpret and extend the musical factors as well as the musical facts of a culture. Such specialists are sensitive to the socio-musical factors contingent on a musical context at the same time as they are the repositories of the theory of composition in a musical arts tradition. Socio-musical factors here categorize those non-musical circumstances of a music-making situation that inform the architecture of a performance-composition; while musical facts are the essential elements of creative configurations that furnish musical arts theory.

Generatiewandelingen in Doorn en andere onderwijs- en beleidsprojecten

Levensgeschiedenissen

Toelichting

Heel wat leerlingen in het VWO en studenten in het HBO houden zich in hun onderwijs met generaties bezig. Zij schrijven er werkstukken over en komen steeds vaker in aanvulling hierop ook met videoreportages. Vooral vakken zoals maatschappijleer, geschiedenis, economie en management lenen zich goed voor scripties en afstudeerwerkstukken over generaties.

Hierbij werken de leerlingen veelal met levensgeschiedenissen van leden van generaties. Daarbij gaat het om een aanpak, die als de ‘life histories approach’ bekend staat.

De ‘life histories approach’ wordt veelvuldig in de geschiedwetenschappen en de sociologie toegepast. Meerdere hoofdstukken in dit boek bevatten voorbeelden van deze toepassing.

Omdat te verwachten is dat het boek Generaties van geluksvogels en pechvogels veel leerlingen tot het toepassen van generaties in hun onderwijs zal inspireren, komen nu enkele voorbeelden aan de orde. Als eerste voorbeeld zijn interviews te noemen met senioren, die tot de Vooroorlogse en Stille generatie behoren. Hoe zijn hun jeugdjaren verlopen en welke effecten heeft hun formatieve periode op hun verdere levensloop gehad? Welke indrukken zijn hen bijgebleven van de ‘Culturele Revolutie’ van het eind van de jaren zestig en het begin van de jaren zeventig? Hoe hebben zij van de economisch gunstige jaren negentig geprofiteerd en hoe hebben zij zich voorbereid op de jaren na ingang van hun pensioen?

From The Web – openculture.com

Open Culture brings together high-quality cultural & educational media for the worldwide lifelong learning community. Web 2.0 has given us great amounts of intelligent audio and video. It’s all free. It’s all enriching. But it’s also scattered across the web, and not easy to find. Our whole mission is to centralize this content, curate it, and give you access to this high quality content whenever and wherever you want it. Free audio books, free online courses, free movies, free language lessons, free ebooks and other enriching content — it’s all here. Open Culture was founded in 2006.

Open Culture brings together high-quality cultural & educational media for the worldwide lifelong learning community. Web 2.0 has given us great amounts of intelligent audio and video. It’s all free. It’s all enriching. But it’s also scattered across the web, and not easy to find. Our whole mission is to centralize this content, curate it, and give you access to this high quality content whenever and wherever you want it. Free audio books, free online courses, free movies, free language lessons, free ebooks and other enriching content — it’s all here. Open Culture was founded in 2006.

Enjoy: http://www.openculture.com