A New Leader’s Big Banking Opportunity To Improve Global Development

Will the New Development Bank and the Contingent Reserve Arrangement be able to fulfill their original mission with the arrival of the new bank president Dilma Rousseff?

The first event of President Lula da Silva’s long-awaited visit to China in mid-April 2023 is the official swearing-in ceremony of Dilma Rousseff as president of the New Development Bank (popularly known as the BRICS Bank) on April 13. The appointment of the former president of Brazil to the post demonstrates the priority that Lula will give to the BRICS countries (Brazil, China, India, Russia, and South Africa) in his government. In recent years, BRICS has been losing some of its dynamism. One of the reasons was the retreat of Brazil—which had always been one of the engines of the group—in a choice made by its right-wing and far-right governments (2016-2022) to align with the United States.

A New Momentum for BRICS?

After the last summit meeting in 2022, hosted by Beijing and held online, the idea of expanding the group was strengthened and more countries are expected to join BRICS this year. Three countries have already officially applied to join the group (Argentina, Algeria, and Iran), and several others are already publicly considering doing so, including Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Egypt, Nigeria, and Mexico.

The BRICS countries occupy an increasingly important place in the world economy. In GDP PPP, China is the largest economy, India is third, Russia sixth, and Brazil eighth. BRICS now represents 31.5 percent of the global GDP PPP, while the G7 share has fallen to 30 percent. They are expected to contribute over 50 percent of global GDP by 2030, with the proposed enlargement almost certainly bringing that forward.

Bilateral trade between BRICS countries has also grown robustly: trade between Brazil and China has been breaking records every year and reached $150 billion in 2022; between Brazil and India, there was a 63 percent increase from 2020 to 2021, reaching more than $11 billion; Russia tripled exports to India from April to December 2022 compared to the same period the preceding year, expanding to $32.8 billion; while trade between China and Russia jumped from $147 billion in 2021 to $190 billion in 2022, an increase of about 30 percent.

The conflict in Ukraine has brought them closer together politically. China and Russia have never been more aligned, with a “no limits partnership,” as visible from President Xi Jinping’s recent visit to Moscow. South Africa and India have not only refused to yield to NATO pressure to condemn Russia for the conflict or impose sanctions on it, but they have moved even closer to Moscow. India, which in recent years has been closer to the United States, seems to be increasingly committed to the Global South’s strategy of cooperation.

The NDB, the CRA, and the Alternatives to the Dollar

The two most important instruments created by BRICS are the New Development Bank (NDB) and the Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA). The first has the objective of financing several development projects—with an emphasis on sustainability—and is regarded as a possible alternative to the World Bank. The second could become an alternative fund to the IMF, but the lack of strong leadership since its inauguration in 2015 and the absence of a solid strategy from the five member countries has prevented the CRA from taking off.

Currently, one of the major strategic battles for the Global South is the creation of alternatives to the hegemony of the dollar. As the Republican U.S. Senator Marco Rubio confessed in late March, the United States will increasingly lose its ability to sanction countries if they decrease their use of dollars. Almost once every week, there is a new agreement between countries to bypass the dollar, like the one recently announced by Brazil and China. The latter already has similar deals with 25 countries and regions.

Right now, there is a working group within BRICS whose task it is to propose its own reserve currency for the five countries that could be based on gold and other commodities. The project is called R5 due to the coincidence that all the currencies of BRICS countries start with R: renminbi, rubles, reais, rupees, and rands. This would allow these countries to slowly increase their growing mutual trade without using the dollar and also decrease the share of their international dollar reserves.

Another untapped potential so far is the use of the Contingent Reserve Arrangement (totaling $100 billion) to rescue insolvent countries. When a country’s international reserves run out of dollars (and it can no longer trade abroad or pay its foreign debts), it is forced to ask for a bailout from the IMF, which takes advantage of the country’s desperation and lack of options to impose austerity packages with cuts in state budgets and public services, privatizations, and other neoliberal austerity measures. For decades, this has been one of the weapons of the United States and the EU to ensure the implementation of neoliberalism in the countries of the Global South.

Right now, the five BRICS members have no issues at all with international reserves, but countries like Argentina, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Ghana, and Bangladesh find themselves in a bad situation. If they could access the CRA, with better conditions for repaying the loans, this would mean a political breakthrough for BRICS, which would begin to demonstrate their ability to build alternatives to the financial hegemony of Washington and Brussels.

The NDB would also need to start de-dollarizing itself, having more operations with the currencies of its five members. For instance, from the $32.8 billion of projects approved so far at NDB, around $20 billion was in dollars, and around the equivalent of $3 billion was in Euros. Only $5 billion was in RMB and very little was in other currencies.

To reorganize and expand the NDB and the CRA will be a huge challenge. The leaderships of the five countries will need to be aligned on a common strategy that ensures that both instruments fulfill their original missions, which won’t be easy. Dilma Rousseff, an experienced and globally respected leader, brings hope for a new beginning. Rousseff fought against Brazil’s civil-military dictatorship in the 1960s and 1970s and spent three years in prison for it. She became one of President Lula’s key ministers in the 2000s, and she was elected Brazil’s first female president and then won reelection (2010 and 2014). She was in office until she was overthrown by a coup based on fraudulent grounds by Congress (2016)—which has already admitted the fraud. She just returned to political life to run one of the most promising institutions in the Global South. After all, President Dilma Rousseff has never shied away from huge challenges.

Author Bio:

This article was produced by Globetrotter.

Marco Fernandes is a researcher at Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. He is the co-editor of Dongsheng. He is a member of the No Cold War collective. He lives in Beijing.

Source: Globetrotter

Fifty Years After Chile’s Coup, The First Year Of Popular Unity

Ten days after the 1973 coup against the Popular Unity (UP) government of President Salvador Allende, the military opened the Río Chico concentration camp on Dawson Island, located in the Strait of Magellan, near the southern tip of Chile. The island had served as an extermination camp by a Catholic order between 1891 and 1911 to confine the Selk’nam and Kawésqar peoples, who died due to overcrowding, the spread of disease, and the cold.

The coup regime sent 38 officials of the UP government to the Compañía de Ingenieros del Cuerpo de Infantería Marina (COMPINGIM) naval base and then to the Río Chico camp. It also sent hundreds of political prisoners to Punta Arenas, near Dawson Island. The officials were interrogated, tortured, and forced to work on the island’s infrastructure. The Río Chico camp was dismantled in 1974.

One of the prisoners at the camp was Miguel Lawner, an architect who led the government’s Urban Improvement Corporation (CORMU). During his imprisonment, Lawner walked around the prison to calculate the size of his room, the buildings at the camp, and the camp itself. He drew the layout for the camp but then destroyed it for fear of discovery by the guards. When he was in exile in Denmark in 1976, Lawner redrew the plans from memory. “The function creates the organ,” he said. “I developed an organ: the drawing, capable of fulfilling the function of leaving testimony of our captivity.”

During his imprisonment, Lawner told me, he worried that the military might accuse him of corruption for his leadership of CORMU. “I was trying to calculate how many millions of dollars had been [spent] in my name,” he recalled. “I calculated it to be between $150 million and $180 million. Later, I learned that the military spent six months investigating me and came to the conclusion that they owed me a per diem!”

The UP government (1970-1973) felt that the ministries of Housing and Public Works should be the engine of the economy, as “the two easiest institutions to mobilize,” Lawner said. Other areas, such as industrialization, “required more prolonged prior studies.” “In housing,” Lawner told me, “if you have a vacant lot, the next day you can be building.” In addition, there was a huge need for housing. The CORMU management decided to speed up the bureaucratic procedures and authorize the immediate disbursement of funds through an official, who was Lawner. “Our first year of government was a year of marvelous irresponsibility,” Lawner told me with a smile on his face.

Never Deviate From the Fundamentals

During the 1970 campaign for the presidency, Lawner accompanied Allende to a camp on the banks of the Mapocho River, where the people lived “outside the walls of society.” As they left the camp, Allende said to Lawner, “Even if things go badly for us, to get these comrades out of the mud—for that, it would be worthwhile for them to elect me president.” One year into the government, Lawner said, “We delivered the first houses of Villa San Luis. In April ’72 we had this project completely delivered: a thousand houses, the great majority of which corresponded to these two camps, el encanto and el ejemplo, which sat on the banks of the Mapocho River.” The main task of the UP government, he said, was “to resolve the fundamental demands of the sectors that had always been dispossessed.”

Under Lawner’s leadership, the CORMU officials—not all of them part of the UP project—postponed vacations and worked without overtime pay. “We gave all these officials the conviction that they were operating for the benefit of the common good and not, obviously, for the enrichment of a private company or the banks. In other words, they knew that they were working so that people could live better.” Also, he said, the objective of “making things beautiful” was imposed, arguing “that in social housing, beauty does not have to be the birthright only of the rich.”

The Explosion of the Countryside

Lawner recalled his great pride at the UP government’s nationalization of copper, its delivery of houses, and its role in the “explosion of the agrarian world.” The agrarian reform and the law for peasant unionization were passed in 1962, before the UP government. However, agrarian workers “continued to exist like serfs from feudal times,” Lawner noted. A week into his presidency, Allende was invited by the peasants of Araucanía to a meeting to which he brought his minister of agriculture, Jacques Chonchol. When an Indigenous leader spoke, Allende leaned over to Chonchol and said, “Listen, minister, I think you should remain here.” The minister, who “had to send for even his toothbrush,” remained there for three months, beginning his term installed in the countryside. Half a million hectares were transferred to the landless in the first year of the government.

The UP’s first year, Lawner recalled, was a “year of unbridled aspirations.” “For a person like me who was never a public official, the feeling of power is infinite, and the conviction that you are capable of doing anything is equally infinite… we promised more than we were capable of doing [having done three or four times more than the most that had ever been done in the history of the housing ministry], but everything we could do was done because of what is now lacking: the commitment of the officials. You have to have good leadership, it is true, but if you don’t have the commitment of the base, there is nothing you can do.”

Generations Contaminated by the Model

When we talked about the differences between the experiences at the end of the first year of the UP and the first year of Chile’s current President Gabriel Boric’s progressive government, Lawner pointed out that, in Chile “we have effectively been fed for 50 years the neoliberal doctrine of a formation contradictory to what you require in a progressive government. Imperceptibly, generations were formed that are, in my opinion, corrupted by the model. It is incomprehensible to them any other way.”

The current president of Chile’s Senate is Juan Antonio Coloma, a man of the extreme right. “When the 50th anniversary of the coup comes this September,” Lawner told me, “Coloma will be the country’s second most important political official.” Fascism’s rise, he said, is a global phenomenon, not only taking place in Chile. But Lawner does not despair. “You cannot determine when there is a spark that lights the fire again, but there is no doubt that it is going to happen.”

Author Bio:

Globetrotter

Taroa Zúñiga Silva is a writing fellow and the Spanish media coordinator for Globetrotter. She is the co-editor with Giordana García Sojo of Venezuela, Vórtice de la Guerra del Siglo XXI (2020). She is a member of the coordinating committee of Argos: International Observatory on Migration and Human Rights and is a member of the Mecha Cooperativa, a project of the Ejército Comunicacional de Liberación.

Source: Globetrotter

The World Bank And The BRICS Bank Have New Leaders And Different Outlooks

In late February 2023, U.S. President Joe Biden announced that the United States had placed the nomination of Ajay Banga to be the next head of the World Bank, established in 1944. There will be no other official candidates for this job since—by convention—the U.S. nominee is automatically selected for the post. This has been the case for the 13 previous presidents of the World Bank—the one exception was the acting president Kristalina Georgieva of Bulgaria, who held the post for two months in 2019. In the official history of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), J. Keith Horsefield wrote that U.S. authorities “considered that the Bank would have to be headed by a U.S. citizen in order to win the confidence of the banking community, and that it would be impracticable to appoint U.S. citizens to head both the Bank and the Fund.” By an undemocratic convention, therefore, the World Bank head was to be a U.S. citizen and the head of the IMF was to be a European national (Georgieva is currently the managing director of the IMF). Therefore, Biden’s nomination of Banga guarantees his ascension to the post.

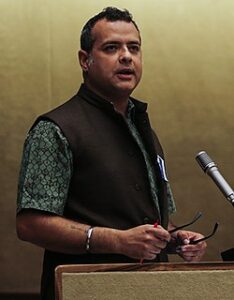

A month later, the New Development Bank’s Board of Governors—which includes representatives from Brazil, China, India, Russia, and South Africa (the BRICS countries) as well as one person to represent Bangladesh, Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates—elected Brazil’s former president Dilma Rousseff to head the NDB, popularly known as the BRICS Bank. The BRICS Bank, which was first discussed in 2012, began to operate in 2016 when it issued its first green financial bonds. There have only been three managing directors of the BRICS Bank—the first from India (K.V. Kamath) and then the next two from Brazil (Marcos Prado Troyjo and now Rousseff to finish Troyjo’s term). The president of the BRICS Bank will be elected from its members, not from just one country.

Banga will come to the World Bank, whose office is in Washington, D.C., from the world of international corporations. He spent his entire career in these multinational corporations, from his early days in India at Nestlé to his later international career at Citigroup and Mastercard. Most recently, Banga was the head of the International Chamber of Commerce, an “executive” of multinational corporations that was founded in 1919 and is based in Paris, France. As Banga says, during his time at Citigroup, he ran its microfinance division, and, during his time at Mastercard, he made various pledges regarding the environment. Nonetheless, he has no experience in the world of development finance and investment. He told the Financial Times that he would turn to the private sector for funds and ideas. His resume is not unlike that of most U.S. appointees to head the World Bank. The first president of the World Bank was Eugene Meyer, who built the chemical multinational Allied Chemical and Dye Corporation (later Honeywell) and who owned the Washington Post. He too had no direct experience working on eradicating poverty or building public infrastructure. It was through the World Bank that the United States pushed an agenda to privatize public institutions. Men such as Banga have been integral to the fulfillment of that agenda.

Dilma Rousseff, meanwhile, comes to the BRICS Bank with a different resume. Her political career began in the democratic fight against the 21-year military dictatorship (1964-1985) that was inflicted on Brazil by the United States and its allies. During Lula da Silva’s two terms as president (2003-2011), Dilma Rousseff was a cabinet minister and his chief of staff. She took charge of the Programa de Aceleração do Crescimento (Growth Acceleration Program) or PAC, which organized the anti-poverty work of the government. Because of her work in poverty eradication, Dilma became known popularly as the “mãe do PAC” (mother of PAC). A World Bank study from 2015 showed that Brazil had “succeeded in significantly reducing poverty in the last decade”; extreme poverty fell from 10 percent in 2001 to 4 percent in 2013. “[A]pproximately 25 million Brazilians escaped extreme or moderate poverty,” the report said. This poverty reduction was not a result of privatization, but of two government schemes developed and established by Lula and Dilma: Bolsa Família (the family allowance scheme) and Brasil sem Misería (the Brazil Without Extreme Poverty plan, which helped families with employment and built infrastructure such as schools, running water, and sewer systems in low-income areas). Dilma Rousseff brings her experience in these programs, the benefits of which were reversed under her successors (Michel Temer and Jair Bolsonaro).

Banga, who comes from the international capital markets, will manage the World Bank’s net investment portfolio of $82.1 billion as of June 2022. There will be considerable attention to the work of the World Bank, whose power is leveraged by Washington’s authority and by its work with the International Monetary Fund’s debt-austerity lending practices. In response to the debt-austerity practices of the IMF and the World Bank, the BRICS countries—when Dilma was president of Brazil (2011-2016)—set up institutions such as the Contingent Reserve Arrangement (as an alternative to the IMF with a $100 billion corpus) and the New Development Bank (as an alternative to the World Bank, with another $100 billion as its initial authorized capital). These new institutions seek to provide development finance through a new development policy that does not enforce austerity on the poorer nations but is driven by the principle of poverty eradication. The BRICS Bank is a young institution compared to the World Bank, but it has considerable financial resources and will need to be innovative in providing assistance that does not lead to endemic debt. Whether the new BRICS Think Tank Network for Finance will be able to break with the IMF’s orthodoxy is yet to be seen.

Rousseff chaired her first BRICS Bank meeting on March 28. Banga will likely be appointed at the World Bank-IMF meeting in mid-April.

Author Bio:

This article was produced by Globetrotter.

Vijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor, and journalist. He is a writing fellow and chief correspondent at Globetrotter. He is an editor of LeftWord Books and the director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. He is a senior non-resident fellow at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China. He has written more than 20 books, including The Darker Nations and The Poorer Nations. His latest books are Struggle Makes Us Human: Learning from Movements for Socialism and (with Noam Chomsky) The Withdrawal: Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan, and the Fragility of U.S. Power.

Source: Globetrotter

The Fear Of AI Is Overblown—And Here’s Why

The unprecedented popularity of ChatGPT has turbocharged the AI hype machine. We are being bombarded daily by news articles announcing humankind’s greatest invention—Artificial Intelligence (AI).

AI is “qualitatively different,” “transformational,” “revolutionary,” “will change everything,”—they say. OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT, announced a major upgrade of the technology behind ChatGPT called GPT4.

Already, Microsoft researchers are claiming that GPT4 shows “sparks of Artificial General Intelligence” or human-like intelligence – the Holy grail of AI research. Fantastic claims are made about reaching the point of “AI Singularity” of machines equalling and then surpassing human intelligence.

The business press talks about hundreds of millions of job losses as AI would replace humans in a whole host of professions. Others worry about a sci-fi-like near future where super-intelligent AI goes rogue and destroys or enslaves humankind. Are these predictions grounded in reality, or is this just over-the-board hype that the Tech industry and the VC hype machine are so good at selling?

The current breed of AI Models are based on things called “Neural Networks.” While the term “neural” conjures up images of an artificial brain simulated using computer chips, the reality of AI is that neural networks are nothing like how the human brain actually works. These so-called neural networks have no similarity with the network of neurons in the brain. This terminology was, however, a major reason for the artificial “neural networks” to become popular and widely adopted despite its serious limitations and flaws.

“Machine Learning” algorithms currently used are an extension of statistical methods that lack theoretical justification for extending them this way. Traditional statistical methods have the virtue of simplicity. It is easy to understand what they do, when and why they work. They come with mathematical assurances that the results of their analysis are meaningful, assuming very specific conditions. Since the real world is complicated, those conditions never hold, and as a result, statistical predictions are seldom accurate. Economists, epidemiologists and statisticians acknowledge this and then use intuition to apply statistics to get approximate guidance for specific purposes in specific contexts. These caveats are often overlooked, leading to the misuse of traditional statistical methods with sometimes catastrophic consequences, as in the 2008 Great Financial Crisis or the LTCM blowup in 1998, which almost brought down the global financial system. Remember Mark Twain’s famous quote, “Lies, damned lies and Statistics.”

Machine learning relies on the complete abandonment of the caution which should be associated with the judicious use of statistical methods. The real world is messy and chaotic and hence impossible to model using traditional statistical methods. So the answer from the world of AI is to drop any pretense at theoretical justification on why and how these AI models, which are many orders of magnitude more complicated than traditional statistical methods, should work. Freedom from these principled constraints makes the AI Model “more powerful.” They are effectively elaborate and complicated curve-fitting exercises which empirically fit observed data without us understanding the underlying relationships.

But it’s also true that these AI Models can sometimes do things that no other technology can do at all. Some outputs are astonishing, such as the passages ChatGPT can generate or the images that DALL-E can create. This is fantastic at wowing people and creating hype. The reason they work “so well” is the mind-boggling quantities of training data—enough to cover almost all text and images created by humans. Even with this scale of training data and billions of parameters, the AI Models don’t work spontaneously but require kludgy ad-hoc workarounds to produce desirable results.

Even with all the hacks, the models often develop spurious correlations, i.e., they work for the wrong reasons. For example, it has been reported that many vision models work by exploiting correlations pertaining to image texture, background, angle of the photograph and specific features. These vision AI Models then give bad results in uncontrolled situations. For example, a leopard print sofa would be identified as a leopard; the models don’t work when a tiny amount of fixed pattern noise undetectable by humans is added to the images or the images are rotated, say in the case of a post-accident upside down car. ChatGPT, for all its impressive prose, poetry and essays, is unable to do simple multiplication of two large numbers, which a calculator from the 1970s can do easily.

The AI Models do not have any level of human-like understanding but are great at mimicry and fooling people into believing they are intelligent by parroting the vast trove of text they have ingested. For this reason, computational linguist Emily Bender called the Large Language Models such as ChatGPT and Google’s BART and BERT “Stochastic Parrots” in a 2021 paper. Her Google co-authors—Timnit Gebru and Margaret Mitchell—were asked to take their names off the paper. When they refused, they were fired by Google.

This criticism is not just directed at the current large language models but at the entire paradigm of trying to develop artificial intelligence. We don’t get good at things just by reading about them, that comes from practice, of seeing what works and what doesn’t. This is true even for purely intellectual tasks such as reading and writing. Even for formal disciplines such as Maths, one can’t get good at Maths without practicing it. These AI Models have no purpose of their own. They, therefore, can’t understand meaning or produce meaningful text or images. Many AI critics have argued that real intelligence requires social “situatedness.”

Doing physical things in the real world requires dealing with complexity, non-linearly and chaos. It also involves practice in actually doing those things. It is for this reason that progress has been exceedingly slow in Robotics: current Robots can only handle fixed repetitive tasks involving identical rigid objects, such as in an assembly line. Even after years of hype about driverless cars and vast amounts of funding for its research, fully automated driving still doesn’t appear feasible in the near future.

Current AI development based on detecting statistical correlations using “neural networks,” which are treated as black-boxes, promotes a pseudoscience-based myth of creating intelligence at the cost of developing a scientific understanding of how and why these networks work. Instead, they emphasize spectacles such as creating impressive demos and scoring in standardized tests based on memorized data.

The only significant commercial use cases of the current versions of AI are advertisements: targeting buyers for social media and video streaming platforms. This does not require the high degree of reliability demanded from other engineering solutions; they just need to be “good enough.” And bad outputs, such as the propagation of fake news and the creation of hate-filled filter bubbles, largely go unpunished.

Perhaps a silver lining in all this is, given the bleak prospects of AI singularity, the fear of super-intelligent malicious AIs destroying humankind is overblown. However, that is of little comfort for those at the receiving end of “AI decision systems.” We already have numerous examples of AI decision systems the world over denying people legitimate insurance claims, medical and hospitalization benefits and state welfare benefits. AI systems in the United States have been implicated in imprisoning minorities to longer prison terms. There have even been reports of withdrawal of parental rights to minority parents based on spurious statistical correlations, which often boil down to them not having enough money to properly feed and take care of their children. And, of course, on fostering hate speech on social media. As noted linguist Noam Chomsky wrote in a recent article, “ChatGPT exhibits something like the banality of evil: plagiarism and apathy and obviation.”

Author Bio:

Bappa Sinha is a veteran technologist interested in the impact of technology on society and politics.

Source: Globetrotter

Credit Line: This article was produced by Globetrotter

We Are Living Through A Paradigm Shift in Our Understanding Of Human Evolution

An interview with Professor Chris Stringer, one of the leading experts on human evolution.

There’s a paradigm shift underway in our understanding of the past 4 million years of human evolution: ours is a story that includes combinations with other Homo species, spread unevenly across today’s populations—not a neat and linear evolutionary progression.

Technological advances and a growing body of archaeological evidence have allowed experts in the study of human origins and prehistory to offer an increasingly clear, though complex, outline of the bio-historical process that produced today’s human population and cultures.

For the most part, the public is presented with new findings as interesting novelty items in the news and science coverage. The fuller picture, and the notion that this information has valuable implications for society and our political arrangements, doesn’t usually percolate into public consciousness, or in centers of influence.

But there is an emerging realization in the expert community that humanity can greatly benefit from making this material a pillar of human education—and gradually grow accustomed to an evidence-based understanding of our history, behavior, biology, and capacities. There’s every indication that a better understanding of ourselves strengthens humanity as a whole and makes connection and cooperation more possible.

The process will realistically take decades to take root, and it seems the best way at this point to accelerate that process is in articulating the big picture, and giving people key footholds and scientific reference points for understanding.

I reached out to discuss some of the bigger conclusions that are emerging from the research with Professor Chris Stringer, who has been at the forefront of human evolutionary understanding for decades. Stringer helped formulate the “Out of Africa” model of our species’ origins and continues to pursue pioneering projects at the UK Natural History Museum in London as research leader in human origins in the Department of Earth Sciences.

Jan Ritch-Frel: A good place to start is that we know that today’s humans produced fertile offspring with relative Homo species that had separated from us hundreds of thousands of years ago, and this went on with ancestor species for as far back as scientists are able to trace. This is against a backdrop that for primate species it was possible to produce fertile offspring with other species sharing a common ancestor as far back as 2 million years—with a generally decreasing chance of success across the passage of time and divergence between Homo species.

Chris Stringer: We know that our species produced some fertile offspring with Neanderthals, and with Denisovans. We also have negative evidence that there were limits on infertility between some of the Homo species because we don’t find a lot more evidence of it in our genomes (at least at the level at which we can detect it)—thus matings between more distantly related species either didn’t occur, were not fertile, or we can’t detect them at the level of our current technology.

There are barriers, and we know that in our genomes today, there are areas of deserts where there’s zero Neanderthal and Denisovan DNA. And we know that some of those deserts are in areas that influence things like speech and vocalization, and how the brain works. There are also suggestions that male children may have been less fertile or infertile compared with the female children of those hybrid matings. At the level we can detect it, there is no strong evidence so far of infertility between Homo sapiens and our more distant relatives such as Homo floresiensis or Homo naledi.

So we don’t yet know all of the Homo species which could have hybridized or did hybridize during the last 2 million years, but certainly some of them would have been interfertile. We know that we, Neanderthals, and Denisovans were interfertile, for example.

Ritch-Frel: Unpacking what you’ve said here, it changes the coordinates of how we explain human evolution to ourselves—not a linear progression, but a series of combinations, of different groups that occasionally produced advantages for survival. In some cases, survival for a migrating Homo population could be assisted by hybridizing with a resident species that had survived in a region for hundreds of thousands of years or more, picking up their adaptions—to the immune system, to the ability to process oxygen, or other traits—not to mention the informational exchange of culture and lifestyle.

The more one learns about this, the easier it is to see that the passage of time is better thought of as just an ingredient in the human evolutionary story. With this in mind, it’s easier to grasp how far astray the concept of “primitive” can take us in understanding ourselves and our evolutionary process.

As the world begins to put this information at the center of human education, it’s so important to get the root words right as best we can.

Stringer: “Archaic” and “modern,” “human” and “non-human”—they’re all loaded terms. What’s a human? And there are many different definitions of what a species is.

There are some people who only use “human” for sapiens, and then the Neanderthals even wouldn’t be human. I don’t agree with that, because it means that we mated with “non-humans” in the last 50,000 years, which I think makes the conversation very difficult.

In my view, the term “human” equates to being a member of the genus Homo. So I regard the Neanderthals, rhodesiensis, and erectus as all being human.

And the terms “modern” and “archaic”—these are difficult terms. And I’ve tried to move away from them now because on the one hand, the term “modern” is used for modern behavior, and it’s also used for modern anatomy, so these terms get confused. For example, some ancient human fossil findings have been described as “anatomically modern” but not “behaviorally modern”—I think that’s just too confusing to be useful.

When we look at the early members of a Homo species, instead of having the term “archaic,” as in having “archaic traits,” I think it’s clearer if we use the term “basal.” Basal puts us on a path without the confusion and baggage that can come with terms like “archaic,” “primitive,” and “modern.” In this usage, “basal” is a relative term, but at least one where we can come up with criteria (such as skeletal traits) to delineate it.

It helps here to consider the evolutionary process outside of Homo sapiens. Neanderthals had a process of evolution as well from the period they split off with our common ancestor. Neanderthals at the end of their time were very derived, quite different from how they started potentially 600,000 years ago, and yet under conventional thinking they are called “archaic” (compared with us “moderns”). Over the period of hundreds of thousands of years, they developed a number of new physical features that were not there in the common ancestor with Homo sapiens. For example, they developed a face that was pulled forward at the middle, a spherical cranial shape in rear view—even some of the ear bones were a different shape. And like us, they evolved a bigger brain. The derived Homo neanderthalensis looked quite different from their ancestors 300,000 years earlier.

So let’s scrap the verbal framework of “primitive” and “archaic” and “modern” and go with “basal” and “derived” along both our and the Neanderthal lineage. Read more

Inside The Fight For LGBTQ+ Rights In Africa

The National Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission (NGLHRC) gained a historic win at the Kenyan Supreme Court on February 24, 2023. It was finally able to register as an official nongovernmental organization (NGO), after a 10-year legal battle in a country where homosexuality is outlawed.

However, the LGBTQ+ community’s celebrations were cut short by a wave of backlash.

A day later, local organizations reported an immediate increase in “verbal and physical attacks,” and in coastal cities, large anti-LGBTQ+ demonstrations were held.

Similar battles are currently being waged across Africa over what count as legitimate ways of loving and whose persecution is justified. Queerphobic rhetoric is used by politicians for narrow political gain. Ghanaian anti-LGTBQ+ campaigner Sam George said that “Ghanaian culture forbids homosexuality” and Kenyan MP Farah Maalim characterized existing as a person who is LGTBTQ+ as being “worse than murder.”

Old colonial laws that criminalized same-sex activity and gender variance were left intact after countries gained independence. Many Africans remained ignorant about precolonial Africa where queerness was present and regularly celebrated, because those histories were maligned. Today these colonial-era laws are still used to oppress LGBTQ+ Africans, who receive no state support and also find their attempts to support each other hindered by bigotry.

In the 21st century, Western influence has intensified state-sponsored homophobia in Africa. This form of neocolonialism mimics the initial colonization of Africa through Christian missionaries. Since 2007, at least $54 million from right-wing U.S. churches has flooded the continent to fight “against LGBT rights and access to safe abortion, contraceptives, and comprehensive sexuality education.” Prominent anti-LGBTQ+ politicians such as Ugandan Minister of State for Trade, Industry, and Cooperatives David Bahati have received $20 million to campaign heavily for more draconian legislation. It is perhaps no surprise then that in Uganda on March 21, 2023, a new law was passed that will “make homosexual acts punishable by death.”

Other sources of money are being levied positively to support LGBTQ+ people. The Trans and Queer Fund (TQF) is a hopeful example of grassroots organizing grounded in socialist and abolitionist values in Nairobi, Kenya. The fund was founded in March 2020 by Mumbi Makena, a feminist writer and organizer whom I spoke to two days after the NGLHRC win. She formed TQF with her friends during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Among left working-class movements in Nairobi, some TQF team members noticed many viewed “queerness as a distraction” from other socioeconomic issues and there was repeated hostility toward queer and women organizers. While weakening economic growth in Africa affects everyone, mainstream organizations were not ready to grapple with how LGBTQ+ identity further marginalized some Kenyans, nor reach out to them specifically.

However, TQF was committed, and it initially set up a mutual aid system to provide relief funds for LGBTQ+ people whose livelihoods disappeared due to mandated lockdowns. Makena explained that many queer and transgender Kenyans work in the service and hospitality industries, which are more accepting of them. During the pandemic, LGBTQ+-friendly NGOs were constrained by donors and could not repurpose previously allocated funds to COVID-19 relief. However, TQF was able to be agile and responsive from the start, working in an unbureaucratic, nonhierarchical way. TQF works on a volunteer basis online through Twitter and Instagram accounts and distributes funds through mobile money.

Over three years, TQF has raised and disbursed an impressive $50,000 and assisted over 1,000 individuals. It supports its community in inventive ways—covering bus fares for people to attend marches and managing furniture donations for those creating transgender safe houses. The ease of accessing the Trans and Queer Fund means LGBTQ+ people have somewhere to turn if they get disowned by their families or need money for medical treatment after experiencing homophobic violence. The mutual aid relies on contributions coming largely from individuals within Kenya, but also from Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom. It describes its initiative as “working toward a future where all people are free from imperialism, capitalism, cisheteropatriarchy and ethnonationalism.” It encourages everyone who comes into contact with TQF to try to understand it as a commons, a collective resource. The next step for the group, Makena says, is political education, so both fundraisers and beneficiaries can “start to form radical analyses of what is happening in the world.”

NGOs have been instrumental in achieving some successes on behalf of LGBTQ+ Africans. For example, they spearheaded advocacy that led to the decriminalization of homosexuality in Botswana and Angola, in 2019 and 2021, respectively. But the law has its limitations. Without a shift in social attitudes, societies like South Africa, home to what is described as “the most progressive constitution in the world,” still suffer from homophobic violence and discrimination. In 2019, NGOs tried to get the Kenyan Supreme Court to rule that sections 162 and 165 of the Penal Code, which criminalize homosexuality, were unconstitutional, but the legal petition was unsuccessful.

As Makena points out, solely changing the law doesn’t automatically make LGBTQ+ people safer. She warns against narrowing queer liberation to a liberal rights framework that does not address the everyday realities faced by working-class LGBTQ+ people. Makena remarks, “We must forge greater solidarities within left movements in Kenya but also with LGBTQ+ people overseas who are often notably silent on the intersections between anti-imperialism and our fight for queer dignity and safety.”

A ripple effect of homophobic laws is that they can eliminate support for those with HIV/AIDS and sex workers, two groups that sometimes overlap with the LGBTQ+ community. Any outreach may be misrepresented as promoting homosexuality, and in the case of the new Uganda law, anyone “abetting homosexuality” will be punished. With a continent already facing the repercussions of the ‘global gag rule’ that decreased overseas funding for sexual and reproductive health and rights, this will certainly affect health care for both LGBTQ+ and heterosexual people alike.

Due to the severe consequences of foreign interference, it becomes even more crucial for African countries to fund their own welfare systems. While intolerance of LGBTQ+ Africans endures, efforts to organize to meet their needs through initiatives like mutual aid endure. TQF encourages others to set up similar mutual funds to strengthen community. “Long-term,” Makena says, “we don’t want LGBTQ+ people to only be passive beneficiaries of the funds or deradicalized; we want people to reflect on TQF and be active participants in their own liberation, collectively defining the agenda.”

It is long past time that African communities learned to be more accepting of diversity and acknowledged that all our fates are linked. It is worth “returning to the source” to rediscover Indigenous African cultural traditions around gender variance to enable more flexible responses to gay and transgender people today. Freedom in its fullest sense includes the right to privacy, and the right to love and build family structures of one’s choosing. LGBTQ+ Africans, like every other group, should be allowed to organize for their own freedom. We will continue to despite the daily challenges to our humanity.

Author Bio:

This article was produced by Globetrotter

Efemia Chela is an editor and researcher at Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research who manages publishing at Inkani Books. She has an MA in development studies from the University of the Witwatersrand and bylines in publications including the Continent and the Johannesburg Review of Books.

Source: Globetrotter