There Is A Problem With The Infrastructure And Budget Bills — They’re Too Small

The United States is an outlier among advanced democratic countries in terms of societal well-being. In the 2020 Social Progress Index rankings, the U.S. is 28th, in the lower half of the second tier of nations, behind economic powerhouses Cyprus and Greece. The countries that perform best in the societal well-being index adhere to the social democratic model and have strong labor unions and a long tradition of left-wing parties.

The dismal performance of the United States in well-being, which includes having dilapidated and uneven infrastructure, could change in the next few years if the Democrats manage to get their act together and pass the infrastructure and reconciliation bills. These pieces of legislation, although hardly adequate in terms of size to address the country’s urgent needs, would be undoubtedly a step forward in terms of changing the federal government’s priorities, according to Robert Pollin, distinguished professor of economics and co-director of the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. But we have to see whether the so-called U.S. “moderates” (who would be seen as right-wingers in the European political spectrum) inside the Democratic Party can put the interests of the people ahead of those of big business, or whether the so-called “progressives” (who would be seen as “moderates” in most European multi-party systems) will even back the infrastructure bill if the accompanying spending bill fails to get the necessary support. In U.S. politics, change rarely, if ever, comes from the top.

C.J. Polychroniou: After decades of political inaction on a dangerously overstretched infrastructure which lags far behind those of most other advanced countries, the U.S. Senate has finally approved a bipartisan $1 trillion infrastructure package which is on a path to final passage in the House. Lawmakers have also agreed to a $3.5 trillion budget process, although its status remains less certain as some moderate Senate Democrats find the total size of the budget to be too large. But let us first discuss the infrastructure bill whose current proposal targets spending over a five-year period. First, how does the world’s leading economy end up with such poor infrastructure, and what can we expect to be the economic impact of the infrastructure bill?

Robert Pollin: Let’s first be clear on the actual size of the bipartisan infrastructure bill. In fact, the version of the bill that passed in the Senate on August 10 allocates $550 billion over 5 years for the infrastructure investments, not $1 trillion, as widely reported. The bill mostly supports investments in traditional infrastructure areas, such as roads, bridges, airports, rail, ports, water management and the electric grid. It does also provide funds, if to a generally lesser extent, to high-speed internet, public transportation, electric vehicles and charging stations, and climate resilience.

Of course, the total price tag sounds gigantic, but in fact it is quite small, along multiple dimensions. First of all, spread over five years, the total spending averages to $110 billion per year. That is equal to less than one-half of one percent of current overall U.S. economic activity — i.e., U.S. Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In addition, this overall level of spending on upgrading the U.S. infrastructure falls far below what objective analysts have concluded is necessary to bring U.S. infrastructure up to a reasonable level. Specifically, the American Society of Civil Engineers recently concluded that the U.S. would need to spend an average of $260 billion per year for 10 years to bring the U.S. only up to a “B” level of infrastructure quality from its current “C-“ level. So the bipartisan bill provides only about 40 percent of what the leading professional society of civil engineers says is needed for the U.S. to maintain an adequate infrastructure in traditional areas. Without the full funding in the range of $260 billion per year, the civil engineers anticipate the U.S. infrastructure continuing its longstanding pattern of deterioration. Beyond that, this bill also provides only miniscule amounts relative to what is needed to advance a viable U.S. climate stabilization project.

The U.S. infrastructure today is in poor condition today for the simple reason that under 40 years of neoliberalism, the idea of undertaking major public investments in strengthening the domestic economy was pushed to the bottom of the federal government’s priorities. Virtually all Republican members of Congress have been doing this pushing, with enough congressional Democrats following along, regardless of whether a Democrat or Republican was in the White House. The top priorities of these members of Congress have been cutting taxes for the rich and continuing to expand the massive military budget. The military budget for 2021, at $704 billion, is nearly 7 times greater than what would be allocated for all the infrastructure projects if the bipartisan bill were to pass. Passing this bill is certainly preferable than having no new support for infrastructure projects. It will also have a modest positive impact on jobs. But let’s also be clear that this level of funding will produce none of the pressures on the federal budget or on inflation, as is being charged by critics. The funding level is just too small for that.

Noam Chomsky: The US-Led “War On Terror” Has Devastated Much Of The World

Twenty years ago this week, the terrorist organization al-Qaeda, whose origins date back to 1979 when Soviet troops invaded Afghanistan, hijacked four airplanes and carried out suicide attacks against the Twin Towers and the Pentagon in the United States. Shortly thereafter, the administration of George W. Bush embarked on a “global war on terror”: It invaded Afghanistan and, a year later, after having toppled the Taliban government, raised the specter of an “Axis of Evil” comprising Iraq, Iran and North Korea, thereby preparing the stage for more invasions. Interestingly enough, Saudi Arabia, whose royal family, according to certain intelligence reports, had been financing al-Qaeda, was not included on the list. Instead, it was Iraq that the U.S. invaded in 2003, toppling a brutal dictator (Saddam Hussein) who had committed most of his crimes as a U.S. ally and was a sworn enemy of al-Qaeda and of other Islamic fundamentalist terrorist organizations because of the threat they posed to his secular regime.

Twenty years ago this week, the terrorist organization al-Qaeda, whose origins date back to 1979 when Soviet troops invaded Afghanistan, hijacked four airplanes and carried out suicide attacks against the Twin Towers and the Pentagon in the United States. Shortly thereafter, the administration of George W. Bush embarked on a “global war on terror”: It invaded Afghanistan and, a year later, after having toppled the Taliban government, raised the specter of an “Axis of Evil” comprising Iraq, Iran and North Korea, thereby preparing the stage for more invasions. Interestingly enough, Saudi Arabia, whose royal family, according to certain intelligence reports, had been financing al-Qaeda, was not included on the list. Instead, it was Iraq that the U.S. invaded in 2003, toppling a brutal dictator (Saddam Hussein) who had committed most of his crimes as a U.S. ally and was a sworn enemy of al-Qaeda and of other Islamic fundamentalist terrorist organizations because of the threat they posed to his secular regime.

The outcome of the 20-year war on terror, which ended with the Taliban’s return to power, has been disastrous on multiple fronts, as Noam Chomsky pointedly elaborates in a breathtaking interview, which also reveals the massive level of hypocrisy that belies the actions of the global empire.

C.J. Polychroniou: Nearly 20 years have passed since the September 11 terrorist attacks in 2001. With nearly 3,000 dead, this was the deadliest attack on U.S. soil in history and produced dramatic ramifications for global affairs, as well as startling impacts on domestic society. I want to start by asking you to reflect on the alleged revamping of U.S. foreign policy under George W. Bush as part of his administration’s reaction to the rise of Osama bin Laden and the jihadist phenomenon. First, was there anything new to the Bush Doctrine, or was it simply a codification of what we had already seen take place in the 1990s in Iraq, Panama, Bosnia and Kosovo? Second, was the U.S.-NATO led invasion of Afghanistan legal under international law? And third, was the U.S. ever committed to nation-building in Afghanistan?

Noam Chomsky: Washington’s immediate reaction to 9/11/2001 was to invade Afghanistan. The withdrawal of U.S. ground forces was timed to (virtually) coincide with the 20th anniversary of the invasion. There has been a flood of commentary on the 9/11 anniversary and the termination of the ground war. It is highly illuminating, and consequential. It reveals how the course of events is perceived by the political class, and provides useful background for considering the substantive questions about the Bush Doctrine. It also yields some indication of what is likely to ensue.

Of utmost importance at this historic moment would be the reflections of “the decider,” as he called himself. And indeed, there was an interview with George W. Bush as the withdrawal reached its final stage, in the Washington Post.

The article and interview introduce us to a lovable, goofy grandpa, enjoying banter with his children, admiring the portraits he had painted of Great Men that he had known in his days of glory. There was an incidental comment on his exploits in Afghanistan and the follow-up episode in Iraq:

Bush may have started the Iraq War on false pretenses, but at least he hadn’t inspired an insurrection that turned the U.S. Capitol into a combat zone. At least he had made efforts to distance himself from the racists and xenophobes in his party rather than cultivate their support. At least he hadn’t gone so far as to call his domestic adversaries “evil.”

“He looks like the Babe Ruth of presidents when you compare him to Trump,” former Senate Majority Leader and one-time Bush nemesis Harry M. Reid (D-Nevada) said in an interview. “Now, I look back on Bush with a degree of nostalgia, with some affection, which I never thought I would do.”

Way down on the list, meriting only incidental allusion, is the slaughter of hundreds of thousands; many millions of refugees; vast destruction; a regime of hideous torture; incitement of ethnic conflicts that have torn the whole region apart; and as a direct legacy, two of the most miserable countries on Earth.

First things first. He didn’t bad-mouth fellow Americans.

Tech “Solutions” Are Pushed By Fossil Fuel Industry To Delay Real Climate Action

This month, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the world authority on the state of Earth’s climate, released the first installment of its Sixth Assessment Report on global warming. It was signed off by 195 member governments. It spells out, in no uncertain terms, the stakes we are up against — and why we have no time to waste in taking dramatic steps to build a green economy.

The IPCC has been publishing reports on the state of the climate and projections for climate change since 1990. The first IPCC report surmised that human activities were behind global warming, but that further scientific evidence was needed. By the time the Fourth Assessment Report came out in 2007, the evidence for human-caused global warming was described as “unequivocal,” with at least a 9 out of 10 chance of being correct. The report confirmed that the warming of the Earth’s surface to record levels was due to the extra heat being trapped by greenhouse gases and called for immediate action to combat the challenge of global warming.

The Sixth Assessment Report finally states in absolute terms that anthropogenic emissions are responsible for the rising temperatures in the atmosphere, lands and the oceans. In other words, the fossil fuel industry is destroying the planet. And, in a similar tone to some of its previous reports, the IPCC warns that time is running out to combat global warming and avoid its worse effects. Without sharp reduction in emissions, we could easily exceed the 2 degrees Celsius (2°C) temperature threshold by the middle of the century.

Of course, we are already in a climate crisis. Heat waves have broken records this summer in many parts of the world, including the Pacific Northwest of the United States and western Canada; wildfires have ravaged huge areas in southern Europe, causing “disaster without precedent” in Greece, Spain and the Italian island of Sardinia; and deadly floods have upended life in China and Germany. Global average temperatures stand now at 1.1°C above pre-industrial levels. A global warming increase of 1.5°C would have a much greater effect on the probability of extreme weather effects like heat waves, floods, droughts and storms, and at 2°C, things get a lot nastier — and for a much larger percentage of the world’s population.

At current trends, it’s most unlikely that global warming can be held at 1.5°C. We have already emitted enough greenhouse gases into the atmosphere to cause 2°C of warming, according to a group of international scientists who published their findings in Nature Climate Change. Even a 3°C increase or more is plausible. In fact, the Network for Greening the Financial System (a group of central banks and supervisors) is already considering climate scenarios with over 3°C of warming, labeling it the “Hot House World.”

Yet, in spite of all the dire climate warnings by IPCC and scores of other scientific studies, the world’s political and corporate leaders continue with their “business-as-usual” approach when it comes to tackling the climate crisis.

Almost immediately after the release of the new IPCC report, the Biden administration urged the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) to increase oil production because higher prices threaten global economic recovery. In fact, Biden’s national security adviser, Jake Sullivan, actually criticized the world’s major oil producers for not producing enough oil. Naturally, Republicans responded by demanding that the Biden administration should encourage U.S. oil producers to boost production instead of turning to OPEC.

Preposterously, the Biden administration seems to think that the best way to tackle global warming caused by anthropogenic emissions is through increasing levels of combustion of fossil fuels.

This must also be the thinking behind China’s affinity for coal, as the world’s biggest carbon polluter is actually financing more than 70 percent of coal plants built globally.

Or perhaps this is all part of a framework that assumes, “We are doomed, so let’s get it over with quickly.”

Chomsky And Pollin: We Can’t Rely On Private Sector For Necessary Climate Action

The new Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) climate assessment report, released on August 9, has finally stated in the most absolute terms that anthropogenic emissions are the cause behind global warming, and that we have no time left in the effort to keep temperature from crossing the 1.5 degrees Celsius threshold. If we fail to take immediate action, we can easily exceed 2 degrees Celsius by the middle of the century.

Nonetheless, it is interesting to note that while the IPCC report underscores the point that the planet is warming faster than expected, it does not directly mention fossil fuels and puts emphasis on carbon removal as a necessary means to tame global warming even though such technologies are still in their infancy.

In this exclusive interview for Truthout, Noam Chomsky, one of the world’s greatest scholars and leading activists, and Robert Pollin, a world-leading progressive economist, offer their own assessments of the IPCC report. Chomsky and Pollin are co-authors of Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (Verso, 2020).

C.J. Polychroniou: Noam, the new IPCC climate assessment report, which deals with the physical science basis of global warming, comes in the midst of extreme heat waves and devastating fires taking place both in the U.S. and in many parts around the world. In many ways, it reinforces what we already know about the climate crisis, so I would like to know your own thoughts about its significance and whether the parties that have “approved” it will take the necessary measures to avoid a climate catastrophe, since we basically have zero years left to do so.

Noam Chomsky: The IPCC report was sobering. Much, as you say, reinforces what we knew, but for me at least, shifts of emphasis were deeply disturbing. That’s particularly true of the section on carbon removal. Instead of giving my own nonexpert reading, I’ll quote the MIT Technology Review, under the heading “The UN climate report pins hopes on carbon removal technologies that barely exist.”

The IPCC report

offered a stark reminder that removing massive amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere will be essential to prevent the gravest dangers of global warming. But it also underscored that the necessary technologies barely exist — and will be tremendously difficult to deploy…. How much hotter it gets, however, will depend on how rapidly we cut emissions and how quickly we scale up ways of sucking carbon dioxide out of the air.

If that’s correct, and I see no reason to doubt it, hopes for a tolerable world depend on technologies that “barely exist — and will be tremendously difficult to deploy.” To confront this awesome challenge is a task for a coordinated international effort, well beyond the scale of John F. Kennedy’s mission to the moon (whatever one thinks of that), and vastly more significant. To leave the task to private power is a likely recipe for disaster, for many reasons, including one brought up by The New York Times report on the idea: “there are risks: The very idea could offer industry an excuse to maintain dangerous habits … some experts warn that they could hide behind the uncertain promise of removing carbon later to avoid cutting emissions deeply today.” The greenwashing that is a constant ruse.

The significance of the IPCC report is beyond reasonable doubt. As to whether the necessary measures will be taken? That’s up to us. We can have no faith in structures of power and what they will do unless pressed hard by an informed public that prefers survival to short-term gain for the “masters of the universe.”

The immediate U.S. government reaction to the IPCC report was hardly encouraging. President Joe Biden sent his national security adviser, Jake Sullivan, to censure the main oil-producing countries (OPEC) for not raising oil production high enough. The message was captured in a headline in the London Financial Times: “Biden to OPEC: Drill, Baby, Drill.”

Biden was sharply criticized by the right wing here for calling on OPEC to destroy life on Earth. MAGA principles demand that U.S. producers should have priority in this worthy endeavor.

Bob, what’s your own take on the IPCC climate assessment report, and do you find anything in it that surprises you?

Robert Pollin: In total, the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report on the physical basis of climate change is 3,949 pages long. So there’s a whole lot to take in, and I can’t claim to have done more than initially review the 42-page “Summary for Policymakers.” Two things stand out from my initial review. These are, first, the IPCC’s conclusion that the climate crisis is rapidly become more severe and, second, that their call for undertaking fundamental action has become increasingly urgent, even relative to their own 2018 report, “Global Warming of 1.50C.” It is important to note that this hasn’t always been the pattern with the IPCC. Thus, in its 2014 Fifth Assessment Report, the IPCC was significantly more sanguine about the state of play relative to its 2007 Fourth Assessment Report. In 2014, they were focused on a goal of stabilizing the global average temperature at 2.0 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, rather than the 1.5 degrees figure. As of 2014, the IPCC had not been convinced that the 1.5 degrees target was imperative for having any reasonable chance of limiting the most severe impacts of climate change in terms of heat extremes, floods, droughts, sea level rises and biodiversity losses. The 2014 report concluded that reducing global CO2 emissions by only 36 percent as of 2050 could possibly be sufficient to move onto a viable stabilization path. In this most recent report, there is no equivocation that hitting the 1.5 degrees target is imperative, and that to have any chance of achieving this goal, global CO2 emissions must be at zero by 2050.

This new report does also make clear just how difficult it will be to hit the zero emissions target, and thus to remain within the 1.5 degrees of warming threshold. But it also recognizes that a viable stabilization path is still possible, if just barely. There is no question as to what the first and most important single action has to be, which is to stop burning oil, coal and natural gas to produce energy. Carbon-removal technologies will likely be needed as part of the overall stabilization program. But we should note here that there are already two carbon-removal technologies that operate quite effectively. These are: 1) to stop destroying forests, since trees absorb CO2; and 2) to supplant corporate industrial practices with organic and regenerative agriculture. Corporate agricultural practices emit CO2 and other greenhouses gases, especially through the heavy use of nitrogen fertilizer, while, through organic and regenerative agriculture, the soil absorbs CO2. That said, if we don’t stop burning fossil fuels to produce energy, then there is simply no chance of moving onto a stabilization path, no matter what else is accomplished in the area of carbon-removal technologies.

I would add here that the main technologies for building a zero-emissions economy — in the areas of energy efficiency and clean renewable energy sources — are already fully available to us. Investing in energy efficiency — through, for example, expanding the supply of electric cars and public transportation systems, and replacing old heating and cooling systems with electric heat pumps — will save money, by definition, for all energy consumers. Moreover, on average, the cost of producing electricity through both solar and wind energy is already, at present, about half that of burning coal combined with carbon capture technology. At this point, it is a matter of undertaking the investments at scale to build the clean energy infrastructure along with providing for a fair transition for the workers and communities who will be negatively impacted by the phase-out of fossil fuels.

Average Global Temperature Has Risen Steadily Under 40 Years Of Neoliberalism

Since the advent of neoliberalism 40 years ago, societies virtually all over the world have undergone profound economic, social and political transformations. At its most basic function, neoliberalism represents the rise of a market-dominated world economic regime and the concomitant decline of the social state. Yet, the truth of the matter is that neoliberalism cannot survive without the state, as leading progressive economist Robert Pollin argues in the interview that follows. However, what is unclear is whether neoliberalism represents a new stage of capitalism that engenders new forms of politics, and, equally important, what comes after neoliberalism. Pollin tackles both of these questions in light of the political implications of the COVID-19 pandemic, as most governments have implemented a wide range of monetary and fiscal measures in order to address economic hardships and stave off a recession.

Robert Pollin is distinguished professor of economics and co-director of the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst and author of scores of books, including Back to Full Employment (2012), Greening the Global Economy (2015) and Climate Crisis and the Global Green new Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (co-authored with Noam Chomsky, 2020).

C.J. Polychroniou: Neoliberalism is a politico-economic project associated with policies of privatization, deregulation, globalization, free trade, austerity and limited government. Moreover, these principles have reigned supreme in the minds of most policymakers around the world since the early 1980s, and continue to do so. Is neoliberalism a new stage of capitalism?

Robert Pollin: Let’s first be clear on what we mean by “neoliberalism.” The term neoliberalism draws on the classical meaning of the word “liberalism.” Classical liberalism is the political philosophy that embraces the virtues of free-market capitalism and the corresponding minimal role for government interventions. According to classical liberalism, free-market capitalism is the only effective framework for delivering widely shared economic well-being. In this view, only free markets can increase productivity and average living standards while delivering high levels of individual freedom and fair social outcomes. Policy interventions to promote economic equality within capitalism — through, for example, taxing the rich, big government spending on social programs, or regulating market activities through, for example, decent minimum wage standards and regulations to prevent financial markets from becoming gambling casinos — will always end up doing more harm than good, according to this view.

For example, establishing living wage standards as the legal minimum — at, say $15 an hour or higher — would cause unemployment to rise, since, according to classical liberalism, employers won’t be willing to pay unskilled workers more than what the free market determines they are worth. Similarly, regulating financial markets will inhibit capitalists from undertaking risky investments that can raise living standards. Classical liberals will argue that the Wall Street Masters of the Universe are infinitely more qualified than government bureaucrats in deciding what to do with their own money. And if the Wall Street investors make dumb decisions, then so be it; let them fail. In that way, [classical liberalism says] the free market rewards smart decisions and punishes bad ones, all to the greater benefit of the whole society.

Now to neoliberalism: Neoliberalism is a contemporary variant of classical liberalism that became dominant worldwide around 1980, beginning with the elections of Margaret Thatcher in the U.K. and Ronald Reagan in the United States. At that time, it was certainly a new phase of capitalism. Thatcher’s dictum that “there is no alternative” to neoliberalism became a rally cry, supplanting what had been, since the end of World War II, the dominance of Keynesianism and social democracy in global economic policymaking. In the high-income countries of Western Europe and North America along with Japan, in particular, this Keynesian/social democratic version of capitalism featured, to varying degrees, a commitment to low unemployment rates, decent levels of support for working people and workplace conditions, extensive regulations of financial markets, public ownership of significant financial institutions and high levels of public investment.

Of course, this was still capitalism. Disparities of income, wealth and opportunity remained intolerably high, along with the social malignancies of racism, sexism and imperialism. Ecological destruction, in particular global warming, was also beginning to gather force over this period, even though few people took notice at the time. Nevertheless, all told, Keynesianism and social democracy produced dramatically more egalitarian as well as more stable versions of capitalism than the neoliberal regime that supplanted these models.

It is critical to understand that neoliberalism was never a project to replace social democracy with true free-market capitalism. Rather, contemporary neoliberals are committed to free-market policies when they support the interests of big business and the rich as, for example, with lowering regulations in the workplace and financial markets. But these same neoliberals become far less insistent on free market principles when invoking such principles might damage the interests of big business, Wall Street and the rich.

An obvious example is the historically unprecedented levels of support provided during the COVID recession to prevent economic collapse. Just in 2020 in the U.S. for example, the federal government pumped nearly $3 trillion into the economy, equal to about 14 percent of total economic activity (GDP) to prevent a total economic collapse. On top of that, the U.S. Federal Reserve injected nearly $4 trillion — equal to about 20 percent of GDP — to avoid a Wall Street meltdown. Of course, pumping government money into the U.S. economy, at a level equal to roughly one-third of total GDP, all in no more than one year’s time, completely contradicts any notion of free-market, minimal government capitalism.

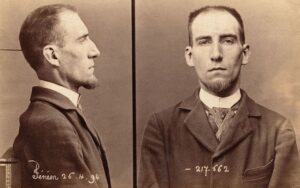

Félix Fénéon, kunstcriticus en anarchist

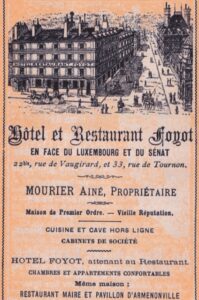

Dat de Franse dichter Laurent Tailhade behalve zijn avondmaaltijd een oog moest missen, was een meer dan sneu gevolg van de bomaanslag die kunstkenner en –criticus Félix Fénéon op 4 april 1894 pleegde op het restaurant van Hôtel Foyot aan de Rue de Tournon in Parijs.

Het was vooral sneu omdat Tailhade Fénéon persoonlijk kende en ook diens anarchistische opvattingen deelde. Zijn verwondingen weerhielden Tailhade er echter niet van in de jaren daarna in zijn werk het anarchisme volop uit te dragen.

Ministerie

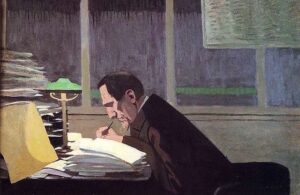

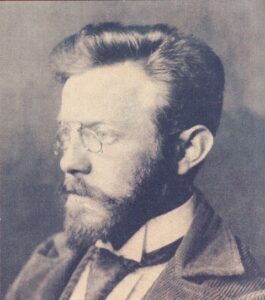

Félix Fénéon (1861-1944) groeide op in de Bourgogne maar vertrok al snel naar Parijs. Op zijn twintigste kreeg hij een baan als klerk op het Ministerie van Oorlog. Hij zou er dertien jaar blijven werken. Daarnaast redigeerde hij voor uitgeverijen werk van Arthur Rimbaud en Lautréamont. Met zijn dandyachtige voorkomen – puntbaard, wandelstok, zwarte cape – was hij in kunstkringen een opvallende verschijning. Wekelijks bezocht hij de populaire kunstsalon van Stéphane Mallarmé. Naast zijn baan op het ministerie werd hij kunstcriticus bij het tijdschrift La Libre Revue. Ook schreef hij gezaghebbende artikelen over kunst en literatuur voor bladen als La Vogue en La Revue wagnérienne. Hij was de ontdekker van de schilder Georges Seurat en was bevriend met de schilder Paul Signac, die hem op een schilderij vereeuwigde. Ook de kunstenaars Toulouse-Lautrec en Félix Valleton maakte portretten van Fénéon. Hij was een onvermoeibaar promotor van het werk Seurat en Signac, die beiden gezien worden als de wegbereiders van het pointillisme. Voor deze stijl en andere daaraan gelieerde kunststromingen bedacht Fénéon de term neonimpressionisme.

Anarchisten

Fénéon kreeg eveneens contacten in anarchistische kringen en hij ging schrijven voor het toonaangevende anarchistische tijdschrift L’En-Dehors van de anarchist Zo d’Axa en voor Revue anarchiste. Toen Zo d’Axa zijn toevlucht zocht in Londen nam Fénéon de redactie van L’En-Dehors over. Aan het tijdschrift werd onder meer meegewerkt door Octave Mirbeau. Jean Grave, Sébastien Faure, Bernard Lazare, Tristan Bernard en de Belgische anarchist Émile Verhaeren. Hij raakte bevriend met de Nederlandse anarchist Alexander Cohen en met ‘anarchist van de daad’ Émile Henry, die later de beruchte bomaanslag op het Café Terminus zou plegen. Soms logeerde Henry bij Fénéon of bij Cohen thuis. Al eerder had Fénéon Henry al eens aan een jurk geholpen, om in vermomming de politie te kunnen ontlopen.

Aanslagen

De uit Leeuwarden afkomstige Cohen (1864-1961) was na een redacteurschap bij Recht voor Allen van Domela Nieuwenhuis overhaast naar Parijs verhuisd. In Nederland werd hij gezocht wegens majesteitsschennis. Tijdens een rijtour van Koning Willem III had hij geroepen: ‘Leve Domela Nieuwenhuis! Leve het socialisme! Weg met Gorilla!’.

In Parijs ging hij schrijven voor de anarchistische bladen L’En-Dehors en Le Père peinard en werd hij correspondent voor Recht voor Allen. In de Franse hoofdstad werden Fénéon en Émile Henry zijn beste vrienden.

Henry wilde in 1892 de eisen van stakende mijnarbeiders bij de Carmoux mijnmaatschappij kracht bijzetten en plaatste een bom bij het kantoor van de maatschappij in Parijs. De bom werd echter ontdekt en meegenomen naar een politiebureau in de Rue des Bons-enfants. Daar ontplofte de bom alsnog waarbij vijf politiemannen om het leven kwamen.

Zijn volgende aanslag was een wraakneming voor de executie van de anarchist Auguste Vailllant, ter dood veroordeeld wegens het plegen van een bomaanslag op de Chambre des Députés, de Kamer der Afgevaardigen. Op 12 februari 1894 plaatste Henry een bom onder een tafeltje in het drukbezochte Café Terminus bij het Gare St. Lazare. Eén persoon kwam om het leven en twintig mensen raakten gewond. Henry werd gearresteerd en in mei 1894 terechtgesteld.

Restaurant

Restaurant

Fénéon, die vond dat zijn eigen schriftelijke bijdragen aan het verkondigen van de anarchistische boodschap niet voldoende effect hadden, nam zich voor de vertegenwoordigers van de bourgeoisie in het hart te treffen. Op 4 april 1894 verstopte hij een bom in een bloempot en toog ermee naar de zetel van de Franse senaat, gevestigd in het paleis in de Jardin du Luxembourg. Daar bleek hij echter niet in de buurt van het bewaakte gebouw te kunnen komen, waarop hij besloot de bom te plaatsen bij het tegenover gelegen Hôtel Foyot, een door veel parlementariërs bezochte eetgelegenheid. Hij plaatste de bloempot in de vensterbank van het restaurant, stak de lont aan en wandelde rustig naar de Place de l’Odéon, waar hij op de bus richting Clichy sprong. Door de ontploffing sneuvelden ramen en stortten kroonluchters van het plafond omlaag. Alleen de dichter Tailharde raakte gewond, het kostte hem een oog.

Huiszoeking

Vanwege zijn anarchistische activiteiten werd Fénéon al enige tijd door de politie in de gaten gehouden. Een dag na de aanslag doorzocht de politie zijn woning maar kon daar geen verdachte aanwijzingen ontdekken. De huiszoeking moest wel op een misverstand berusten, concludeerde de politie-inspecteur en bood excuses aan. Op het politiebureau ondertekende Fénéon een verklaring waarin hij ontkende aanhanger van het anarchisme te zijn, en vertrok naar zijn kantoor op het Ministerie van Oorlog. Daar bewaarde hij in een la van zijn bureau een fles kwikzilver en enige ontstekers – hem door Henry in bruikleen gegeven – die echter door de politie werden ontdekt. Dit en zijn anarchistische activiteiten waren voldoende om hem te arresteren. Met de aanslag op het Hôtel Foyot is hij echter nooit meer in verband gebracht.

Proces

Proces

De Franse regering was de aanslagen beu en vaardige een serie strenge wetten uit waarbij iedere anarchistische activiteit strafbaar werd gesteld. Dertig vooraanstaande anarchisten werd ‘organisatie van criminele activiteiten’ ten laste gelegd, onder wie Sébastien Faure, Jean Grave, Paul Reclus, Félix Fénéon en Alexander Cohen. Voor de Franse staat draaide dit ‘Procès des trente’ echter uit op een mislukking. Slechts acht beklaagden werden veroordeeld, vier van hen bij verstek, onder wie Reclus en Alexander Cohen. De laatste had inmiddels de wijk naar Londen genomen. Pas in 1899 zou hij naar Parijs terugkeren.

Tijdens het proces wist Fénéon op vaak humoristische wijze aanklachten tegen hem te pareren. Bij een beschuldiging van een ‘nauw contact’ met de Duitse anarchist Kampfmeyer, antwoordde hij: ‘Ik spreek geen Duits en Kampfmeyer spreekt geen Frans. Hoe nauw moet dat contact dan geweest zijn?’ En toen hij beticht werd een vooraanstaande anarchist te hebben gesproken ‘achter een gaslantaarn’, was zijn antwoord: ‘Neem me niet kwalijk, Monsieur le Préfect, maar wat is de achterkant van een gaslantaarn?’ Fénéon werd vrijgesproken maar zijn baan op het ministerie moest hij wel opgeven.

Drie regels

Als redacteur kon hij aan de slag bij het vooraanstaande kunsttijdschrift La Revue Blanche. Ook daarin vestigde hij voortdurend de aandacht op het werk van Seurat en Signac en in 1900 organiseerde hij de eerste overzichtstentoonstelling van schilderijen van Seurat. In het tijdschrift publiceerde hij ook werk van Marcel Proust, Appolinaire, Paul Claudel en vertaalde hij Jane Austen en brieven van Edgar Allen Poe.

In 1906 ging hij voor de krant Le Matin de dagelijkse pagina faits divers samenstellen: berichten uit stad en provincie, die –zo was de opdracht – in de krant niet langer dan drie regels mochten zijn. Nieuwtjes over inbraken, ongelukken, crimes passionnel, moorden, branden en ander leed, werden door Fénéon geminimaliseerd tot gevatte beschrijvingen van het gebeurde, vaak met een kwinkslag of woordspeling, soms met kort commentaar. Hij puzzelde met woorden, zoals een dichter of liedjesschrijver. Ieder bericht vormt een verhaal op zich en roept vragen op over het hoe en waarom. Intrigerende, vermakelijke of hilarische, tragische of ontroerende berichten die in veel gevallen de aanzet tot een roman zouden kunnen zijn. De berichten zijn te vergelijken met de collages die Picasso en Braque jaren later uit gescheurde kranten samenstelden, maar doen ook denken aan de collages van Kurt Schwitters en aan de wijze waarop William Burroughs in de jaren vijftig kranten verknipte en omsmeed tot een roman. Dankzij het knipwerk van Fénéons vriendin zijn twaalfhonderd stukjes bewaard gebleven en in 2009 in boekvorm verschenen. Fénéon schreef de stukjes om in zijn onderhoud te voorzien, maar wellicht vond hij ook voldoening bij het in kaart brengen van het verval in de Franse samenleving. De lezer kon zelf zijn conclusie trekken.

In 1906 ging hij voor de krant Le Matin de dagelijkse pagina faits divers samenstellen: berichten uit stad en provincie, die –zo was de opdracht – in de krant niet langer dan drie regels mochten zijn. Nieuwtjes over inbraken, ongelukken, crimes passionnel, moorden, branden en ander leed, werden door Fénéon geminimaliseerd tot gevatte beschrijvingen van het gebeurde, vaak met een kwinkslag of woordspeling, soms met kort commentaar. Hij puzzelde met woorden, zoals een dichter of liedjesschrijver. Ieder bericht vormt een verhaal op zich en roept vragen op over het hoe en waarom. Intrigerende, vermakelijke of hilarische, tragische of ontroerende berichten die in veel gevallen de aanzet tot een roman zouden kunnen zijn. De berichten zijn te vergelijken met de collages die Picasso en Braque jaren later uit gescheurde kranten samenstelden, maar doen ook denken aan de collages van Kurt Schwitters en aan de wijze waarop William Burroughs in de jaren vijftig kranten verknipte en omsmeed tot een roman. Dankzij het knipwerk van Fénéons vriendin zijn twaalfhonderd stukjes bewaard gebleven en in 2009 in boekvorm verschenen. Fénéon schreef de stukjes om in zijn onderhoud te voorzien, maar wellicht vond hij ook voldoening bij het in kaart brengen van het verval in de Franse samenleving. De lezer kon zelf zijn conclusie trekken.

In Rouen heeft M. Colombe zich gisteren met één kogel gedood. In maart had zijn vrouw hem er drie in het lijf geschoten en de echtscheiding was op handen.

Met haar tachtig jaren werd Mme Saout uit Lambézellec stilaan bang dat de dood haar zou overslaan. Toen haar dochter even de deur uit was, knoopte zij zich op.

In Falaise verwelkomde oud-burgemeester M. Ozanne de deurwaarder Vieillot met geweerschoten om zich, na één treffer, het leven te benemen.

Jacquot, eerste bediende bij een kruidenier in Les Maillys, heeft zich en zijn vrouw om het leven gebracht. Hij was ziek, zij niet.

Zittend in de vensterbank van het open raam, reeg G. Laniel, negen, uit Meaux haar laarsjes dicht. Bijna. Tot zij achterover op de keien smakte.

(uit: Félix Fénéon, Het nieuws in drie regels, Antwerpen 2009)

Geruchten

Jarenlang deden nog geruchten de ronde dat de aanslag bij Hôtel Foyot het werk van Fénéon was geweest. Fénéon zelf heeft er nooit in het openbaar over gesproken en besteedde er geen aandacht aan. Slechts eenmaal bevestigde hij dat hij de dader was, in een gesprek met Kaya Batut, de vrouw van Alexander Cohen.

Noot

1. Vorig jaar werd in het Moma in New York een grote tentoonstelling aan Fénéon gewijd, waarop onder meer werk van Seurat en Signac te zien was.

Literatuur

Alexander Cohen, In opstand, Amsterdam 1932

John Merriman, The Dynamite Club, New Haven/London 2009

Félix Fénéon, Het nieuws in drie regels, Antwerpen 2009

Joan Ungersma Halperin, Félix Fénéon, Aesthete & Anarchist in Fin-de-Siècle Paris, New Haven/London 1988