Is Russia Really The Reason Why Mali Continues To Push France Away?

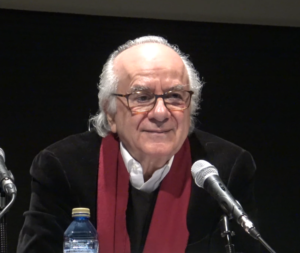

Vijay Prashad

On November 21, 2022, Mali’s interim Prime Minister Colonel Abdoulaye Maïga posted a statement on social media to say that Mali has decided “to ban, with immediate effect, all activities carried out by NGOs operating in Mali with funding or material or technical support from France.” A few days before this statement, the French government cut official development assistance (ODA) to Mali because it believed that Mali’s government is “allied to Wagner’s Russian mercenaries.” Colonel Maïga responded by saying that these are “fanciful allegations” and a “subterfuge intended to deceive and manipulate national and international public opinion.”

Tensions between France and Mali have increased over the course of 2022. The former colonial power returned to Mali with a military intervention in 2013 to combat the rise of Islamist insurgency in the northern half of Mali; in May 2022, the military government of Mali ejected the French troops. That decision in May came after several months of accusations between Paris and Bamako that mirrored the rise of anti-French sentiment across the Sahel region of Africa.

A new burst of anti-colonial feeling has swept through France’s former colonies, where the debates are now centered around breaking with France’s stranglehold on their economies and ending the military intervention by French troops. Since 2019, the countries that are part of the West African Economic and Monetary Union and the Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa have been slowly withdrawing from French control over their economies (for example, in 2020, the French officially announced that for West Africa, it would end the requirement for countries to deposit half their foreign exchange reserves with the French Treasury through the old colonial instrument of the CFA franc). According to a story that circulated in West Africa and the Sahel—given credence by an email sent by an “unofficial adviser” to former U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton—one of the reasons why France’s then-president Nicolas Sarkozy wanted to overthrow Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi in 2011 was because the Libyan leader had proposed a new African currency instead of the CFA franc.

France denies that the reason for this tension with Mali is due to the new anti-colonial mood. The French government says that it is entirely due to Mali’s intimacy with Russia. Mali’s military has increasingly been establishing closer ties with the Russian government and military. Mali’s Defense Minister Colonel Sadio Camara and Air Force Chief of Staff General Alou Boï Diarra are considered to be “the architects” of a deal made between the Malian military and the Wagner group in 2021 to bring in several hundred mercenaries into Mali as part of the campaign against jihadist groups.

Wagner soldiers are in Mali, but they are not the cause of the rift between Paris and Bamako. The anti-colonial temper predates the entry of Wagner, which France is using as an excuse to cover up its humiliation.

Author Bio:

This article was produced by Globetrotter.

Vijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor, and journalist. He is a writing fellow and chief correspondent at Globetrotter. He is an editor of LeftWord Books and the director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. He is a senior non-resident fellow at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China. He has written more than 20 books, including The Darker Nations and The Poorer Nations. His latest books are Struggle Makes Us Human: Learning from Movements for Socialism and (with Noam Chomsky) The Withdrawal: Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan, and the Fragility of U.S. Power

Source: Globetrotter

‘The Ax Always Falls On The Most Vulnerable’: Pakistan Demands Debt Cancellation And Climate Justice

More than 1,700 people have been killed in floods that continue to submerge parts of Pakistan. Amid this crisis, activists are demanding debt cancellation and climate reparations.

Even as the floodwaters have receded, the people of Pakistan are still trying to grapple with the death and devastation the floods have left in their wake.

The floods that swept across the country between June and September have killed more than 1,700 people, injured more than 12,800, and displaced millions as of November 18.

The scale of the destruction in Pakistan was still making itself apparent as the world headed to the United Nations climate conference COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, in November. Pakistan was one of two countries invited to co-chair the summit. It also served as chair of the Group of 77 (G77) and China for 2022, playing a critical role in ensuring that the establishment of a loss and damage fund was finally on the summit’s agenda, after decades of resistance by the Global North.

“The dystopia has already come to our doorstep,” Pakistan’s Minister for Climate Change Sherry Rehman told Reuters.

By the first week of September, pleas for help were giving way to protests as survivors, living under open skies and on the sides of highways, were dying of hunger, illness, and lack of shelter.

Parts of the Sindh province, which was hit the hardest, including the districts of Dadu and Khairpur remained inundated until the middle of November. Meanwhile, certain areas of impoverished and predominantly rural Balochistan, where communities have been calling for help since July, waited months for assistance.

“Initially the floods hit Lasbela, closer to Karachi [in Sindh], so people were able to provide help, but as the flooding spread to other parts of Balochistan the situation became dire,” Khurram Ali, general secretary of the Awami Workers Party (AWP), told Peoples Dispatch. “The infrastructure of Balochistan has been neglected, the roads are damaged, and dams and bridges have not been repaired.”

The floods precipitated a massive infrastructural collapse that continues to impede rescue and relief efforts—more than 13,000 kilometers of roads and 439 bridges have been destroyed, according to a November 18 report by the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA), Pakistan.

Speaking to Peoples Dispatch in September, Taimur Rahman, secretary-general of the Mazdoor Kissan Party (PMKP), said that the government had been “unable to effectively provide aid on any large scale, or to ensure that it reached where it was supposed to go.” This has also led to the emergence of profiteering, as gangs seize aid from trucks and sell it, Rahman added.

In these circumstances, left and progressive organizations such as the AWP and PKMP have attempted to fill the gaps by trying to provide people with basic amenities to survive the aftermath of this disaster.

Cascading Crises

On September 17, the WHO warned of a “second disaster” in Pakistan—“a wave of disease and death following this catastrophe, linked to climate change.”

The WHO has estimated that “more than 2,000 health facilities have been fully or partially damaged” or destroyed across the country, at a time when diseases such as COVID-19, malaria, dengue, cholera, dysentery, and respiratory illnesses are affecting a growing share of the population. More than 130,000 pregnant women are in need of urgent health care services in Pakistan, which already had a high maternal mortality rate even prior to the floods.

Damage to the agricultural sector, with 4.4 million acres of crops having been destroyed, has stoked fears of impending mass hunger. In a July report by the World Food Program, 5.9 million people in Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and Sindh provinces were already estimated to be in the “crisis” and “emergency” phases of food insecurity between July and November 2022.

At present, an estimated 14.6 million people will be in need of emergency food assistance from December 2022 to March 2023, according to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Malnutrition has already exceeded emergency threshold levels in some districts, especially in Sindh and Balochistan.

Not only was the summer harvest destroyed but the rabi or winter crops like wheat are also at risk, as standing water might take months to recede in some areas, like Sindh. Approximately 1.1 million livestock have perished so far due to the floods.

This loss of life and livelihood has taken place against the backdrop of an economic crisis, characterized by a current account deficit and dwindling foreign exchange reserves.

Then came the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

As part of its attempt to resume a stalled $6 billion bailout program with the fund, Pakistan’s government imposed a hike in fuel prices and a rollback on subsidies in mid-June.

“The conditions that the IMF placed on us exacerbated the inflation and cost of living crisis,” explained Rahman. “They imposed on Pakistan tax policies that would try to balance the government’s budget on the one hand, but on the other really undermine the welfare of the people and cause such a catastrophic rise in the cost of living that it would condemn millions of people to poverty and starvation.”

By the end of August, the IMF had approved a bailout of more than $1.1 billion. By then, Pakistan’s consumer price index had soared to 27.3 percent, the highest in nearly 50 years, and food inflation increased to 29.5 percent year-on-year. By September, prices of vegetables were up by 500 percent.

“We went to the IMF for $1.1 billion, meanwhile, the damage to Pakistan’s economy is at least $11 billion,” said Rahman. The figure for the damages caused due to the floods now stands at $40 billion, according to the World Bank. “The IMF keeps telling us to lower tariff barriers, to take away subsidies, to liberalize trade, make the state bank autonomous, to deregulate private capital and banking, and to balance the budget,” he added.

“The ax always falls on the most vulnerable,” Rahman said. “Over half of the budget, which in itself is a small portion of the GDP, goes toward debt repayment, another quarter goes to the military and then there’s nothing left. The government is basically bankrupt.”

“The advice of the IMF is always the same—take the state out, let the private market do what it does. Well, look at what it has done: it has destroyed Pakistan’s economy. … Imposing austerity at a time when Pakistan is coping with such massive floods and the economy is in freefall is the equivalent of what the British colonial state did during the Bengal famine—it took food away.”

Pakistan will be forced to borrow more money to pay back its mounting debt, all while IMF conditions hinder any meaningful recovery for the poor and marginalized. The fund has now imposed even tougher conditions on Pakistan to free up $3.5 billion in response to the floods, not nearly large enough to address $30 billion worth of economic damage. The conditions include a hike in gas and electricity prices as well as cuts in development spending.

It is in this context that activists are demanding a total cancellation of debt, and climate reparations for Pakistan.

The Global North Must Pay

Between 2010 and 2019, 15.5 million Pakistanis were displaced by natural disasters. Pakistan has contributed less than 1 percent to global greenhouse gas emissions, but remains at the forefront of the climate crisis.

Delivering the G77 and China’s opening statement at COP27, Pakistan’s Ambassador Munir Akram emphasized, “We are living in an era where many developing countries are already witnessing unprecedented devastating impacts of climate change, though they have contributed very little to it…”

“Enhanced solidarity and cooperation to address loss and damage is not charity—it is climate justice.”

In its February report, the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change acknowledged that “historical and ongoing patterns of inequity such as colonialism” have exacerbated vulnerability to climate change. Yet, even as the Global South faces an existential threat, the Global North actively impedes efforts toward redressal.

“Reparations are about taking back [what] is owed to you,” environmental lawyer Ahmad Rafay Alam told Peoples Dispatch. “As the climate crisis grows… this discourse [of reparations] is going to get stronger. It’s not just going to come from Pakistan, we will hear it from places like Afghanistan where people don’t have the infrastructure and are freezing in the winter… We’ll hear it as the Maldives and the Seychelles start sinking.”

While this struggle plays out globally, there is also justifiable anger within Pakistan over the government’s failure to prepare for the crisis, especially in the aftermath of the deadly floods of 2010.

“Everyone anticipated that this monsoon would be disastrous, and the National Disaster Management Authority had enough time to prepare,” Ali said. “However, there is nothing you can find that [shows what] the NDMA did to prepare for these monsoons. In fact, they do not even have a division to take precautionary measures.”

Holding the government accountable for its lack of preparedness, which might have contained the damage, is crucial, Alam said. However, given the sheer scale of the impact of the climate crisis on the Global South, talking about adaptation has its limitations. As Alam stressed—“There is just no way you can adapt to a 100-kilometer lake that forms in the middle of a province.”

Activists are drawing attention to infrastructure projects the state is pursuing, and how they put the environment and communities at risk. “As reconstruction takes place it is important not to repeat the mistakes of the past,” Alam said.

“The projects that are affecting riverbeds and other sensitive areas are the development projects themselves,” Ali said. He pointed out that development often takes place on agricultural or ecologically sensitive land such as forests, adding to the severity of future crises.

“It is a very dangerous situation now because imperialist profit-making is devastating the climate, affecting regions that are already maldeveloped. We are living under semi-feudal, semi-colonial conditions in Pakistan, with a strong nexus between the imperialist powers and the capitalists, all making money off our misery,” Ali stressed.

“We have no other option but to fight these forces; there is no other option but a people’s revolution.”

Author Bio:

Tanupriya Singh is a writer at Peoples Dispatch and is based in Delhi.

This article was produced in partnership by Peoples Dispatch and Globetrotter.

Source: Globetrotter

The Fed’s Response To Rising Inflation Protects The Wealthy At Workers’ Expense

Robert Pollin – Co-Director of the Political Economy Research Institute (PERI) at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst

The specter of inflation is haunting the world’s economies. Surging prices since 2020, especially in food and energy, have eroded global living standards, though inflation varies considerably across countries. However, inflation is hitting the working class and lower-income people harder than wealthier households, triggering protests around the world, especially in countries with strong trade unions and left-wing political parties. In Europe, governments fearful of social unrest have spent hundreds of billions of euros in an attempt to cushion the impact of inflation. The conservative government in Greece has even sought to restrain the increase in prices in more than 50 basic goods with a “household basket” plan. Meanwhile, in the United States — the richest country in the world — government policies to assist those suffering disproportionately from the surge in prices do not even exist.

Why are prices rising, and why do experts think that high inflation isn’t going away anytime soon? Moreover, what type of policies would we expect from a truly progressive government in an effort to curb inflation and bring wages in line with inflation?

Two leading leftist economists from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, Gerald Epstein and Robert Pollin, shed light on these questions in this exclusive interview for Truthout. Epstein and Pollin are also co-directors of the Political Economy Research Institute (PERI) at UMass-Amherst, which on December 2-3 will host an international conference to explore the causes of inflation and what can be done about it.

C.J. Polychroniou: Bob, the war on Ukraine has not only set back global recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic but also seems to have caused inflationary expectations to soar. Indeed, inflation is haunting most economies around the world, and there seems to be no end in sight for high prices. Why is inflation rising, and what are the main forces behind the creation of large price increases in food, the energy sector and even in housing?

Robert Pollin: Sharply rising inflation rates emerged throughout the world coming out of the 2020-2021 COVID lockdown. According to the International Monetary Fund, the average inflation rate for the overall global economy rose from 3.8 percent in 2019, the year prior to the COVID pandemic onset, to 6.4 percent in 2021, as lockdown conditions from COVID started loosening, and 9.1 percent as of October 2022. For the large high-income economies (G-7 economies), inflation rose from 1.6 percent in 2019 to 5.6 percent in 2021 and to 6.8 percent as of October 2022. The comparable figures for the U.S. economy specifically are 2.1 percent in 2019, 7.4 percent in 2021 and 6.4 percent as of October 2022.

Clearly, the first driver of inflation globally has been the unique economic conditions globally coming out of the COVID lockdown. In particular, the global economy emerged out of the lockdown with supply shortages for a wide range of goods, including oil, food and computer chips, since production of goods had been cut back sharply during the lockdown. On top of that, the shipping industry itself contracted during the lockdown, and has not been able to bounce back quickly. Within the U.S., a major drag has been that there has been, very simply, a shortage of truck drivers to deliver supplies. This has resulted because truck drivers are badly paid. Under COVID conditions, the job also became less safe. One easy solution here would be to raise the pay and improve the safety precautions for the drivers. More people would then want to show up and take these jobs. That still hasn’t happened. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine led to further global supply shortages, in particular for energy and food. This in turn created still more inflationary pressures.

Right-wing commentators like to claim that large government spending levels caused inflation. This position is not entirely wrong, though it is misleading in the way that the right-wing pundits present it. In fact, government spending levels to counteract the COVID lockdown were historically unprecedented throughout the world, amounting to between 15 percent and 30 percent of all economic activity in all major economies. These were government spending levels equal to, if not greater than, World War II. They succeeded in creating a global floor on overall demand — that is, people did still have money in their pockets and bank accounts even while unemployment was spiking with the economic lockdown.

The 2 percent inflation target has primarily been a means of keeping workers’ bargaining power weak and enabling profits and CEO pay to explode.

In other words, overall demand did not fall as much as overall supply. This created a version of the classic mantra on inflation, as resulting from “too much money chasing too few goods.” But consider this problem relative to the alternative that would have resulted under the COVID lockdown in the absence of these government spending injections — i.e., “too little money and too many goods.” That would have produced a major deflation — i.e., falling prices, wages and incomes, along with huge increases in mass unemployment, bankruptcies and a global depression. I have lots of criticisms of the specific ways in which these COVID bailouts were executed. But we are far better off as a result of this government spending, even recognizing how inflation has followed, then to have allowed a global deflation and depression to result.

Under these circumstances of COVID-lockdown and war-related supply shortages, corporations in turn seized the opportunity to mark up their prices and pad their profits margins. Focusing on the U.S. economy, the Financial Times reported on November 28 that, “Margins of retailers and wholesalers have exploded in the past two years. The basic story here is that a combination of broken supply chains, rising input costs, and high demand created pricing power for producers, who raised mark-ups. Those mark-ups … are fueling inflation.” The economist Josh Bivens at the Economic Policy Institute has confirmed this pattern for the U.S., calculating that 54 percent of the price increases for corporations has been due to rising profit margins.

Polychroniou: Can inflation in today’s world be controlled by the actions of national governments? If so, what might a progressive government in the United States be able to do to make prices go down, or otherwise, to increase benefits and wages in line with inflation?

Pollin: The first issue to consider here is how much we should need or want prices to come down. In a paper that I will be presenting at the PERI conference, my coauthor Hanae Bouazza and I show that, considering 130 countries over the 61-year period from 1960-2021, economies have consistently grown at faster rates when inflation ranges between 5 percent and 15 percent as opposed to between 0 percent and 2.5 percent. Generally, this is because when an economy is operating at a high level of activity — with low unemployment rates and strong public sector support — inflation will tend to be somewhat faster. This is not a serious problem as long as workers’ wages and living standards are at least keeping pace with inflation. And as I noted above, this is a far less serious problem than when unemployment is high and wages and living standards are eroding, even while inflation may be at 2 percent or less.

In fact, since the mid-1990s, all high-income countries have been operating under what is termed an “inflation targeting” policy framework. These economies have all set their “inflation targets” at 2 percent inflation. The premise here is that economies perform better when inflation is negligible to nonexistent. But in fact, we have seen in the U.S. that, along with low-to-zero inflation between the early 1990s until the COVID reopening, the buying power of workers’ wages remained stagnant, while the pay for corporate CEOs rose exorbitantly, from being 33 times higher than the average worker in 1978 to 366 times higher in 2019. This is a more than tenfold increase in relative pay for corporate CEOs. So, the 2 percent inflation target has primarily been a means of keeping workers’ bargaining power weak and enabling profits and CEO pay to explode.

Accelerating inflation was harming the real value of wealth held by the top 1 percent and richer strata. The Fed responded by significantly raising interest rates to slow inflation and to try to protect the wealth of the wealthy.

Within this context, it is not surprising that the primary response of policy makers to the global inflationary spike has been to try forcing their economies’ inflation rate down to the 2 percent target rate. Specifically, this has entailed central banks raising the short-term interest rates that they control for the purpose of weakening overall demand in the economy and raising mass unemployment. With mass unemployment rising, worker bargaining power — and along with it, the labor costs faced by businesses — would be expected to decline. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell acknowledged these policy aims clearly, if demurely, in a major speech last August. Powell predicted then that there would “very likely be some softening of labor market conditions” resulting from the Fed raising interest rates.

Despite this singular focus by the Fed and other central banks on raising interest rates and unemployment, this is by no means the only policy tool available that could effectively manage inflation. The Biden administration itself has proposed enacting windfall profit taxes and stricter enforcement of regulations already in place to control corporations monopolistic pricing power. These would counter the excessive mark ups over costs that corporations have been able to impose over the past two years. Additional policy tools could include direct controls in the short term of some key prices, such as oil, along with tighter enforcement of speculation trading on futures markets for oil and food. Still more, increasing infrastructure investments can serve to loosen supply-chain bottlenecks in the short run while raising productivity over the longer term. Advancing a green energy transition — including investments in both energy efficiency and renewable energy — will reduce dependency on volatile fossil fuel markets while also driving down CO2 emissions.

It is possible that these other measures do not operate as forcefully as raising interest rates and unemployment for bringing inflation down to the 2 percent target rate. But the evidence shows that it is not typically necessary to force down inflation to such low levels. Moreover, all of these alternatives offer the critical advantage that they can reduce inflationary pressures without forcing up unemployment rates. It is also critical to note that inflation has been coming down since July. In the U.S., the average rate for the past four months has been 2.7 percent (expressed on an annual basis). At the least, this pattern demonstrates that there is no further need for the Fed to continue trying to force up unemployment in the name of inflation control. Rather, the combination of less stringent inflation-control policies should be more than sufficient now to continue bringing inflation down to an acceptable level.

Polychroniou: Jerry, there are some economists who argue that monetary policy has been the neglected factor behind the recent surge in inflation. Is this a valid argument, especially with regard to inflation in the United States? Moreover, how do central banks control inflation, and how do you assess the role, so far, that central banks and the Fed in particular have played in combatting inflation? It appears that working-class people, globally, are getting the short end of the stick with the policies pursued by central banks in the fight against inflation.

Gerald Epstein is Professor of Economics and a founding Co-Director of the Political Economy Research Institute (PERI) at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Gerald Epstein: The Federal Reserve has two broad areas of responsibility: one is with regard to monetary policy and the second involves financial regulatory policy, which includes both the monitoring and enforcement of financial regulations. When it fails to implement or enforce its regulations sufficiently, then it bails out the financial institutions and markets that have engaged in reckless behavior and are teetering on the edge. Here it is playing its role as “lender of last resort” or more accurately, as the “bailor-in-chief.” To bail out these banks and markets, the Fed tries to keep interest rates very low so they can borrow money cheaply. This also gives banks and wealthy financiers the opportunity to borrow money cheaply and buy and trade financial assets, leading to the massive increases in financial wealth we have observed until recently in the period following the great financial crisis of 2007-2009. Up until the time when Russia invaded Ukraine, the Federal Reserve’s mixture of monetary policy, regulatory (non-) policy and bail-outs led to a gigantic “asset inflation,” but not much of an inflation in the cost of goods and services. The one exception to this may have been in the case of housing and real estate, whose increase in prices were probably partly driven by these low interest rates.

But when supply chain problems from the pandemic hit and Russia’s invasion took hold, then commodity inflation took off. Now the Fed saw that its game of inflating the wealth of the wealthy with low interest rates and bailouts would no longer suffice. The problem: The accelerating inflation was harming the real value of wealth held by the top 1 percent and richer strata. The Fed responded by significantly raising interest rates to slow inflation and to try to protect the wealth of the wealthy. But as Bob Pollin explained, this came at the expense of slower employment growth and even higher unemployment for workers.

As Bob explained, the standard of living of workers and the poor have been significantly hurt by increases in the cost of living associated with the war and supply problems, but higher interest rates, designed to help the wealthy, will only hurt the workers more. Home mortgage costs, interest rates on credit cards and slower wage growth will be the result.

Polychroniou: Assuming you were in a position to affect policymaking in the fight against inflation, what measures would you recommend as an economist of the left?

Epstein: Since Bob discussed this in general, I will focus here on what the Federal Reserve could do. It is often said that the Fed has only one tool — interest rates — and so that is what it is using to fight this inflation. But this is not correct. As the Fed amply showed during the great financial crisis and the onslaught of the COVID pandemic — as well as in previous periods such as during World War II — the Fed has a number of tools in addition to interest rates: these include subsidized lending, asset buying, direct lending for productive purposes, and other more technical tools like asset-based reserve requirements designed to subsidize some lending and penalize other types. If the Fed had the notion (and the political will to pull it off in the face of a potentially hostile Congress), it could lend subsidized credit or buy assets from specialized nonprofit banks devoted to providing low-cost housing; it could provide working capital or buy longer term assets from organizations in communities providing subsidized solar energy and insulation for residences and community buildings; it could provide subsidized credit for farmers and rural communities that are producing healthy food and developing distribution networks that bypass the mega-middle men — buyers, grocery stores etc. that are using their market power to rise food prices. These are just a few examples.

The point is that the Federal Reserve has a huge amount of creative lending and investment strategies during the recent crises mostly to help banks and other financial institutions, but also municipal governments, small businesses and the like, and they could do this again to do two things: Help subsidize key commodities for the working class and poor, and also help increase the supply of key commodities — green energy, healthy food, etc. — that will improve the standard of living of workers in the medium to longer term.

Punishing increases in interest rates are not the only tool the Fed can use, but it is the tool it is choosing.

C.J. Polychroniou is a political scientist/political economist, author, and journalist who has taught and worked in numerous universities and research centers in Europe and the United States. Currently, his main research interests are in U.S. politics and the political economy of the United States, European economic integration, globalization, climate change and environmental economics, and the deconstruction of neoliberalism’s politico-economic project. He is a regular contributor to Truthout as well as a member of Truthout’s Public Intellectual Project. He has published scores of books and over 1,000 articles which have appeared in a variety of journals, magazines, newspapers and popular news websites. Many of his publications have been translated into a multitude of different languages, including Arabic, Chinese, Croatian, Dutch, French, German, Greek, Italian, Japanese, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish and Turkish. His latest books are Optimism Over Despair: Noam Chomsky On Capitalism, Empire, and Social Change (2017); Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (with Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin as primary authors, 2020); The Precipice: Neoliberalism, the Pandemic, and the Urgent Need for Radical Change (an anthology of interviews with Noam Chomsky, 2021); and Economics and the Left: Interviews with Progressive Economists (2021).

The Imperative Of De-Escalation In Ukraine: Negotiations And Possible Solutions

In the West, there are two different competing narratives about the war in Ukraine. The prevailing narrative is that it is a struggle between the “bad guys” and “good guys”. For many, Russia led by dictator Putin represents imperialism and is alone responsible for this unprovoked war, whereas Ukraine represents freedom and democracy as well as courage and heroism. The forces of evil must be won decisively by military means. The likelihood of a nuclear conflict is played down as it would lessen the resolve to reach a total victory.

If the Ukraine war is seen through moral prescriptions, as a struggle between good and evil, like in ancient Manichean thinking, we approach a very dangerous territory in the world of nuclear weapons. Russians have their own version of demonization, with an opposite view on locating the good and the evil. In this black-and-white, moralistic environment, only a few peace proposals have been presented while actors resort to increasingly harsh military measures, stricter sanctions and further escalation of conflict. Generals have become the oracles of the future and politicians and diplomats their servants. Is this really the future we want?

The minority or at least the less vocal view in the West is that reality is much more complicated than what the majority suggests. The unfortunate and short-sighted Russian invasion violates international law and has caused an enormous amount of suffering and turmoil, for the directly warring sides, for Europe, the US and the world, but this invasion was not unprovoked. While there are different ways of articulating the specifics of the narrative, this storyline involves the idea that also the West and the US in particular bear partial responsibility for the tragic outcome of the long process of mutual alienation and escalation of conflict between Russia and the West.[1]

What is more, the escalation has continued to a point where the world is verging on nuclear war. Nothing can justify a nuclear war and yet humankind is now becoming close to the darkest moment of the Cuban Missile Crisis, through brinkmanship and escalation. Nuclear war will be on the horizon unless a peaceful solution is found. China’s president Xi Jinping’s early November plea to stop making threats and prevent the use of nuclear weapons in Europe and Asia may have eased the rhetoric temporarily but is no substitute for the de-escalation of the conflict itself.

The proponents of the first narrative may respond that it is impossible to negotiate in good faith with the Putin regime. The point of ever more extensive military aid to Ukraine and deeper sanctions against Russia is also to undermine the Putin regime in the hope of the emergence of a more peaceful and democratic government in Russia. However, a coup d’état or a sudden revolution of some sort would likely lead to a destabilization of the Russian state, economy, and society. It is not only that we may be seeing a kind of return to the chaotic 1990s but there is also a possibility of dissolution of central political authority and fragmentation, civil strife, even war.

Many Western politicians and the bulk of media people seem to be thinking that the harder the sanctions the better because that will lead to some kind of a breakdown of the Russian economy leading to a regime change. But apart from the fact that the sanctions do not seem to be working the intended way, they hardly consider the consequences. Assuming a breakdown, even if someone would be able to again stabilize the situation in Russia, it is quite likely that the successor system will be a dictatorship, as the army and police are among the few coherent institutions that can keep the huge country from falling apart. Moreover, any loss of central control of Russia’s nuclear weapons would have nightmarish consequences.

Already during the Cold War, many researchers argued that the main danger lies in a situation, which is preceded by a steady erosion of trust and confidence. In this kind of scenario, a crisis may precipitate the first use of nuclear weapons, particularly if the initiator faces a desperate situation and believes that only nuclear weapons might provide an escape from certain defeat and death.[2]

The uncertainties and risks of the current situation have become increasingly blatant. Thus, while President Biden has criticized the Russian invasion harshly from the start, and including in his address to the UN General Assembly on 21 September 2022, the lessons of the Cuban Missile Crisis of the early 1960s seem to have started to resonate at the White House after mid-September. In his address at a fundraising dinner on September 29th Biden put forward some poking questions: “We’re trying to figure out: What is Putin’s off-ramp?” “Where, where does he get off? Where does he find a way out? Where does he find himself in a position that he does not — not only lose face but lose significant power within Russia?”

According to the New York Times[3], the main message that Mr. Biden seemed to be conveying is that he was heeding one of the central lessons of the Cuban Missile Crisis, which unfolded in October 1962. That lesson is that the United States and its allies need to avoid getting Mr. Putin’s back to the wall, forcing him to strike out. “It’s part of Russian doctrine”, he explained to the well-heeled crowd of potential donors to Democratic senatorial campaigns, that “if the motherland is threatened, they’ll use whatever force they need, including nuclear weapons.” This implies an understanding that if the Russians face continuous battlefield victories by NATO-assisted Ukrainian forces, the war will be in a political and military stalemate, where a nuclear strike becomes more and more likely, especially if the leaders’ political and physical survival is at risk.

The White House’s insistence that if Putin uses tactical nuclear weapons the US will respond “with catastrophic consequences” does not help defuse the approaching Armageddon. We do not know what these consequences mean in practice but General Petraeus, former CIA Director, has suggested striking Russian forces, installations and the Black Sea Fleet, destroying them completely with massive conventional arms. But that would be brinkmanship of the highest order. An attack against Russian forces by NATO countries allows or even might force Russia, according to its stated nuclear policy, to launch intercontinental ballistic missiles in return.

In 1962, after having vetoed various strike options proposed by the military – that we now know would have started a nuclear holocaust – President Kennedy eventually proposed a secret deal that was accepted by Soviet First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev. Kennedy suggested removing US nuclear missiles from Turkey secretly if Soviet missiles were removed from Cuba, publicly under UN monitoring. In addition, the US made a public declaration to not invade Cuba again.

During the Cuban crisis, President Kennedy estimated the probability of a nuclear war to be somewhere between one in three and one in two, while other participants in the crisis thought the probability was somewhat lower. Sixty years later, in 2022, we have already seen estimates that the probability of a nuclear war is approaching the heights of the 1962 crisis. For example, in October 2022, Matthew Bunn, Professor of the Practice of Energy, National Security, and Foreign Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School, estimated that the probability of the war in Ukraine turning nuclear is 10-20%.[4] These levels of likelihood are unacceptable. Former US Senator Sam Nunn “has also been sounding the alarm about the threat of an accidental nuclear exchange as a result of a cyber-attack on nuclear command-and-control systems — including by malign actors not directly involved in the conflict who could be confused for a nuclear adversary”[5].

The Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI), a respected international institution established by Senator Nunn and Ted Turner, has for a long time advocated disarmament measures and military confidence-building measures. In face of the increasing escalation potential of the conflict in Ukraine, NTI published on 18 March 2022 a hypothetical scenario of how the world could plunder, unintentionally, into full-scale nuclear war through miscalculation and misinformation under the enormous pressure of the war, including mental and physical stress and sleep deprivation[6]. Numerous war games by the US department of defense and independent research institutions have also simulated the world moving unintentionally to nuclear war in hypothetical scenarios of war-like conditions between the US and Russia. And accidents become more likely when the war is prolonged as it is happening right now.

How to ensure in this dangerous situation that the nuclear war does not start intentionally or accidentally? The prospects are not promising because of the almost complete loss of trust and communication between Russia and NATO. In December 2020, a high-level group of 166 former generals, politicians, ex-diplomats and academics from the US, Europe and Russia, all concerned about increasing risks of nuclear and other military accidents, signed a report entitled ‘Recommendations of the Expert Dialogue on NATO-Russia Military Risk Reduction in Europe’[7]. The talks continued in a smaller group but unfortunately have essentially been moribund after the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

In this serious situation of potential nuclear escalation, the UN Secretary-General could resort to a rarely used leadership measure the founders of the UN Charter endowed to him: the use of Article 99 of the Charter[8]. The Article says that the Secretary-General can “to bring to the attention of the Security Council any matter which in his opinion may threaten the maintenance of international peace and security.” It is in fact difficult to imagine a more urgent and appropriate use of Article 99 than the increased risk of nuclear war in Ukraine. Secretary-General Antonia Guterres has himself said that nuclear tensions are climbing to dangerous levels in his speech at a UN Alliance of Civilizations meeting in Morocco in November 2022.[9] Nuclear Threat Initiative could brief the Council, officially or informally, about the increased risks and propose that the seven recommendations by the NATO-Russia Nuclear Risk talks referred to above should be implemented to the maximum degree possible and official disarmament talks should also be urgently resumed.

We also believe in a nearly absolute and unconditional requirement to de-escalate the conflict through negotiations. This is a war between Russia and Ukraine, with intensive NATO involvement and with long-deteriorating US-Russia relations looming in the background. Any peace agreement must be negotiated by the relevant participants and with appropriate third parties.

On 11 November 2022, the Foundation for Global Governance and Sustainability issued a Call for Armistice in Ukraine. So far five heads of State of Government have co-signed it.[10] The initiative asks for a transition from a general cease-fire to a final peace settlement between Russia and Ukraine which is to be supervised by the United Nations and possibly other international organizations, such as the OSCE. Demilitarization of the occupied areas and a larger demilitarized zone of disengagement between the armed forces of the belligerents could be a part of a wider agreement. The plan also calls for immediate efforts to be focused on repairing civilian infrastructure, including in the areas to be placed under temporary international administration, and on securing an adequate supply of food, water, health care, and energy for the inhabitants.

This is an example of a constructive proposal that stresses the role of common institutions and goes beyond thinking in terms of simple territorial concessions either way. In particular, the option of using the United Nations’ presence in Ukraine is an already much-tested model for the de-escalation of the war and building the elements for peace. Instead of seeing the conflict as a mythic struggle between good and evil, what is needed is a sense of nuance, context, and reciprocal process. The reliance on common institutions and especially the potential of the UN presence on the ground as a tool for de-escalation would be a step in the right direction – even if only a small step in the long march toward a more sustainable and desirable future.

Notes:

[1] For discussions on this point, see Tuomas Forsberg and Heikki Patomäki, Debating the War in Ukraine. Counterfactual Histories and Future Possibilities, Abingdon and New York: Routledge, forthcoming in Dec 2022.

[2] Rudolf Avenhaus, Steven J. Brams, John Fichtner and D. Marc Kilgour, ‘The Probability of Nuclear War’, Journal of Peace Research, 1989, Vol. 26, No. 1, p. 91.

[3] David E Sanger, “In Dealing with Putin Threat, Biden Turns to Lessons of Cuban Missile Crisis”, New York Times, October 7th, 2022.

[4] View expressed in an NPR interview on 4 October 2022, summary available at https://www.npr.org/2022/10/04/1126680868/putin-raises-the-specter-of-using-nuclear-weapons-in-his-war-with-ukraine.

[5] Bryan Bender, “How the Ukraine War Could Go Nuclear”, Politico, 24 March 2022.

[6] Christopher Coletta, “Blundering into a Nuclear War in Ukraine; a Hypothetical Scenario”, Atomic Pulse, Nuclear Threat Initiative, 18 March 2022. Available at https://www.nti.org/atomic-pulse/blundering-into-a-nuclear-war-in-ukraine-a-hypothetical-scenario/.

[7] European Leadership Network, “Recommendations from an experts’ dialogue; de-escalating NATO-Russia military risks”, 6 December 2020.

Available at https://www.europeanleadershipnetwork.org/group-statement/nato-russia-military-risk-reduction-in-europe/

[8] See Tapio Kanninen and Heikki Talvitie,” How to Move the UN Security Council from Hostility to Cooperation”, PassBlue, 22 November 2022, Available at https://www.passblue.com/2022/11/21/how-to-move-from-hostility-to-cooperation-in-the-un-security-council/.

For the history of the use of Article 99 see https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/monthly-forecast/2019-08/in-hindsight-article-99-and-providing-the-security-council-with-early-warning.php

[9] “UN Chief: Nuclear tensions climbing to dangerous levels”, Global Affairs, SmartBrief, 23 November 2022.

[10] The Call is available at https://www.foggs.org/armistice-call-11-nov-2022/.

Heikki Patomäki is a social scientist, activist, and Professor of World Politics at the University of Helsinki. He has published widely in various fields including philosophy, international relations and peace research. Patomäki’s most recent book is The Three Fields of Global Political Economy (Routledge 2022) and, with T.Forsberg, Debating the War in Ukraine. Counterfactual Histories and Possible Futures (Routledge 2023). Previously he has worked as a full professor at The Nottingham Trent University, UK, and RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia, and as a Visiting Professor at Ritsumeikan University, Kyoto, Japan. He is a member of the Finnish Academy of Sciences; a Life Member of Clare Hall, University of Cambridge; and Vice Chair of EuroMemo, a network of European (political) economists.

Dr. Tapio Kanninen, former Chief of Policy Planning at the UN’s Department of Political Affairs in New York, is a member of the Advisory Board of the Foundation for Global Governance and Sustainability (FOGGS). He is also currently President of the Global Crisis Information Network Inc. and a founding member of Climate Leadership Coalition Inc. His latest book is Crisis of Global Sustainability (2013). While at the UN, Kanninen also served as Head of the Secretariat of Kofi Annan’s five Summits with Regional Organizations that also included military alliances like NATO.

10 Suggestions For Lula, New President Of Brazil

Dear President Lula,

When I visited you (Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva) in prison on August 30, 2018, in the brief time that the visit lasted, I experienced a whirlwind of ideas and emotions that remain as vivid today as they were then. A short time before, we had been together at the World Social Forum in Salvador da Bahia. In the penthouse of the hotel where you were staying, we exchanged ideas with Brazilian politician Jacques Wagner about your imprisonment. You still had some hope that the judicial system would suspend the persecutory vertigo that had descended upon you. I, perhaps because I am a legal sociologist, was convinced that this would not happen, but I did not insist. At one point, I had the feeling that you and I were actually thinking and fearing the same thing. A short time later, they were arresting you with the same arrogant and compulsive indifference with which they had been treating you up to that point. Judge Sergio Moro, who had links with the U.S. (it is too late to be naive), had accomplished the first part of his mission by putting you behind bars. The second part would be to keep you locked up and isolated until “his” candidate (Jair Bolsonaro) was elected, one who would give Moro a platform to get to the presidency of the republic later on. This is the third phase of the mission, still underway.

When I entered the premises of Brazil’s federal police, I felt a chill when I read the plaque marking that President Lula da Silva had inaugurated those facilities 11 years earlier as part of his vast program to upgrade the federal police and criminal investigation system in the country. A whirlwind of questions assaulted me. Had the plaque remained there out of oblivion? Out of cruelty? Or to show that the spell had turned against the sorcerer? That a bona fide president had handed the gold to the bandit?

I was accompanied by a pleasant young federal police officer who turned to me and said, “We read your books a lot.” I was shocked. If my books were read and the message understood, neither Lula nor I would be there. I babbled something to this effect, and the answer was instantaneous: “We are following orders.” Suddenly, the Nazi legal theorist Carl Schmitt came to my mind. To be a sovereign is to have the prerogative to declare that something is legal even if is not, and to impose your will bureaucratically with the normality of functional obedience and the consequent trivialization of state terror.

This is how I arrived at your cell, and surely you did not even suspect the storm that was going on inside me. Upon seeing you, I calmed down. I was faced with dignity and humanity that gave me hope for mankind. Everything was normal within the totalitarian abnormality that had enclosed you there: The windows, the gym apparatus, the books, and the television. Our conversation was as normal as everything around us, including your lawyers and Gleisi Hoffmann, who was then the general secretary of the Workers’ Party. We talked about the situation in Latin America, the new (old) aggressiveness of the empire, and the judicial system that had converted into an ersatz military coup.

When the door closed behind me, the weight of the illegal will of a state held hostage by criminals armed with legal manipulations fell back on me once again. I braced myself between revolt and anger and the well-behaved performance expected of a public intellectual who on his way out has to make statements to the press. I did everything, but what I truly felt was that I had left behind Brazil’s freedom and dignity imprisoned so that the empire and the elites in its service could fulfill their objectives of guaranteeing access to Brazil’s immense natural resources, privatization of social security, and unconditional alignment with the geopolitics of rivalry with China.

The serenity and dignity with which you faced a year of confinement is proof that empires, especially decadent ones, often miscalculate, precisely because they only think in the short term. The immense and growing national and international solidarity, which would make you the most famous political prisoner in the world, showed that the Brazilian people were beginning to believe that at least part of what was destroyed in the short term might be rebuilt in the medium and long term. Your imprisonment was the price of the credibility of this conviction; your subsequent freedom was proof that the conviction has become reality.

I am writing to you today first to congratulate you on your victory in the October 30 election. It is an extraordinary achievement without precedent in the history of democracy. I often say that sociologists are good at predicting the past, not the future, but this time I was not wrong. That does not make me feel any more certain about what I must tell you today. Take these considerations as an expression of my best wishes for you personally and for the office you are about to take on as the president of Brazil.

1. It would be a serious mistake to think that with your victory in Brazil’s presidential election everything is back to normal in the country. First, the normal situation prior to former President Jair Bolsonaro was very precarious for the most vulnerable populations, even if it was less so than it is now. Second, Bolsonaro inflicted such damage on Brazilian society that is difficult to repair. He has produced a civilizational regression by rekindling the embers of violence typical of a society that was subjected to European colonialism: the idolatry of individual property and the consequent social exclusion, racism, and sexism; the privatization of the state so that the rule of law coexists with the rule of illegality; and an excluding of religion this time in the form of neo-Pentecostal evangelism. The colonial divide is reactivated in the pattern of friend/enemy, us/them polarization, typical of the extreme right. With this, Bolsonaro has created a radical rupture that makes educational and democratic mediation difficult. Recovery will take years.

2. If the previous note points to the medium term, the truth is that your presidency will be dominated by the short term. Bolsonaro has brought back hunger, broken the state financially, deindustrialized the country, let hundreds of thousands of COVID victims die needlessly, and promised to put an end to the Amazon. The emergency camp is the one in which you move best and in which I am sure you will be most successful. Just two caveats. You will no doubt return to the policies you have successfully spearheaded, but mind you, the conditions are now vastly different and more adverse. On the other hand, everything has to be done without expecting political gratitude from the social classes benefiting from the emergency measures. The impersonal way of benefiting, which is proper to the state, makes people see their personal merit or right in the benefits, and not the merit or benevolence of those who make them possible. There is only one way of showing that such measures result neither from personal merit nor from the benevolence of donors but are rather the product of political alternatives: ensuring education for citizenship.

3. One of the most harmful aspects of the backlash brought about by Bolsonaro is the anti-rights ideology ingrained in the social fabric, targeting previously marginalized social groups (poor, Black, Indigenous, Roma, and LGBTQI+ people). Holding on firmly to a policy of social, economic, and cultural rights as a guarantee of ample dignity in a very unequal society should be the basic principle of democratic governments today.

4. The international context is dominated by three mega-threats: recurring pandemics, ecological collapse, and a possible third world war. Each of these threats is global in scope, but political solutions remain predominantly limited to the national scale. Brazilian diplomacy has traditionally been exemplary in the search for agreements, whether regional (Latin American cooperation) or global (BRICS). We live in a time of interregnum between a unipolar world dominated by the United States that has not yet fully disappeared and a multipolar world that has not yet been fully born. The interregnum is seen, for example, in the deceleration of globalization and the return of protectionism, the partial replacement of free trade with trade by friendly partners. All states remain formally independent, but only a few are sovereign. And among the latter, not even the countries of the European Union are to be counted. You left the government when China was the great partner of the United States and return when China is the great rival of the United States. You have always been a supporter of the multipolar world and China cannot but be today a partner of Brazil. Given the growing cold war between the United States and China, I predict that the honeymoon period between U.S. President Joe Biden and yourself will not last long.

5. You today have a world credibility that enables you to be an effective mediator in a world mined by increasingly tense conflicts. You can be a mediator in the Russia/Ukraine conflict, two countries whose people urgently need peace, at a time when the countries of the European Union have embraced the U.S. version of the conflict without a Plan B; they have therefore condemned themselves to the same fate as the U.S.-dominated unipolar world. You will also be a credible mediator in the case of Venezuela’s isolation and in bringing the shameful embargo against Cuba to an end. To accomplish all this, you must have the internal front pacified, and here lies the greatest difficulty.

6. You will have to live with the permanent threat of destabilization. This is the mark of the extreme right. It is a global movement that corresponds to the inability of neoliberal capitalism to coexist in the next period in a minimal democratic way. Although global, it takes on specific characteristics in each country. The general aim is to convert cultural or ethnic diversity into political or religious polarization. In Brazil, as in India, there is the risk of attributing to such polarization the character of a religious war, be it between Catholics and Evangelicals, or between fundamentalist Christians and religions of African origin (Brazil), or between Hindus and Muslims (India). In religious wars, conciliation is almost impossible. The extreme right creates a parallel reality immune to any confrontation with the actual reality. On that basis, it can justify the cruelest violence. Its main objective is to prevent you, President Lula, from peacefully finishing your term.

7. You currently have the support of the United States in your favor. It is well known that all U.S. foreign policy is determined by domestic political reasons. President Biden knows that, by defending you, he is defending himself against former President Trump, his possible rival in 2024. It so happens that the United States today is the most fractured society in the world, where the democratic game coexists with a plutocratic far right strong enough to make about 25 percent of the U.S. population still believe that Joe Biden’s victory in the 2020 presidential election was the result of an electoral fraud. This far right is willing to do anything. Their aggressiveness is demonstrated by the attempt by one of their followers to kidnap and torture Nancy Pelosi, leader of the Democrats in the House of Representatives. Furthermore, right after the attack, a battery of fake news was put into circulation to justify the act—something that can very well happen in Brazil as well. So, today the United States is a dual country: the official country that promises to defend Brazilian democracy, and the unofficial country that promises to subvert it in order to rehearse what it wants to achieve in the United States. Let us remember that the extreme right started as the official policy of the country. Hyper-conservative evangelicalism started as an American project (see the Rockefeller report of 1969) to combat “the insurrectionary potential” of liberation theology. And let it be said, in fairness, that for a long time its main ally was former Pope John Paul II.

8. Since 2014, Brazil has been living through a continued coup process, the elites’ response to the progress that the popular classes achieved with your governments. That coup process did not end with your victory. It only changed rhythm and tactics. Throughout these years and especially in the last electoral period we have witnessed multiple illegalities and even political crimes committed with an almost naturalized impunity. Besides the many committed by the head of the government, we have seen, for example, senior members of the armed forces and security forces calling for a coup d’état and publicly siding with a presidential candidate while in office. Such behavior should be punished by the judiciary or by compulsory retirement. Any idea of amnesty, no matter how noble its motives may be, will be a trap in the path of your presidency. The consequences could be fatal.

9. It is well known that you do not place a high priority on characterizing your politics as being left or right. Curiously, shortly before being elected president of Colombia, Gustavo Petro stated that the important distinction for him was not between left and right, but between politics of life and politics of death. The politics of life today in Brazil is sincere ecological politics, the continuation and deepening of policies of racial and sexual justice, labor rights, investment in public health care and education, respect for the demarcated lands of Indigenous peoples, and the enactment of pending demarcations. A gradual but firm transition is needed from agrarian monoculture and natural resource extractivism to a diversified economy that allows respect for different socioeconomic logics and virtuous articulations between the capitalist economy and the peasant, family, cooperative, social-solidarity, Indigenous, riverine, and quilombola economies that have so much vitality in Brazil.

10. The state of grace is short. It does not even last 100 days (see President Gabriel Boric in Chile). You have to do everything not to lose the people that elected you. Symbolic politics is fundamental in the early days. One suggestion: immediately reinstate the national conferences (built on bottom-up participatory democracy) to give an unequivocal sign that there is another, more democratic, and more participative way of doing politics.

Chomsky: US Sanctions On Iran Don’t Support The Protests, They Deepen Suffering

Protests have been raging in Iran since mid-September in response to the death of Mahsa Amini, the 22-year-old Kurdish-Iranian woman who died in a hospital in Tehran after being arrested a few days earlier by Iran’s morality police for allegedly breaching the Islamic theocratic regime’s dress code for women. Protesters are widely describing her death as murder perpetrated by the police (the suspicion is that she died from blows to the body), but Iran’s Forensic Organization has denied that account in an official medical report.

Since September, the protests — led by women of all ages in defiance not only of the mandatory dress codes but also against gender violence and state violence of all kinds — have spread to at least 50 cities and towns. Just this week, prominent actors and sports teams have joined the burgeoning protest movement, which is reaching into all sectors of Iranian society.

Women in Iran have a long history of fighting for their rights. They were at the forefront of the 1979 revolution that led to the fall of the Pahlavi regime, though they enjoyed far more liberties under the Shah than they would after the Ayatollah Khomeini took over. As part of Khomeini’s mission to establish an Islamic theocracy, it was decreed immediately after the new regime was put in place that women were henceforth mandated to wear the veil in government offices. Iranian women organized massive demonstrations when they heard that the new government would enforce mandatory veiling. But the theocratic regime that replaced the Shah was determined to quash women’s autonomy. “In 1983, Parliament decided that women who do not cover their hair in public will be punished with 74 lashes,” the media outlet Deutsche Welle reports. “Since 1995, unveiled women can also be imprisoned for up to 60 days.”

But today’s protests are a display of opposition not just to certain laws but to the entire theocratic system in Iran: As Frieda Afary reported for Truthout, protesters have chanted that they want “neither monarchy, nor clergy.” And as Sima Shakhsari writes, the protests are also about domestic economic policies whose effects have been compounded by U.S. sanctions.

The protests have engulfed much of the country and are now supported by workers across industries, professionals like doctors and lawyers, artists and shopkeepers. In response, the regime is intensifying its violent crackdown on protesters and scores of artists, filmmakers and journalists have been arrested or banned from work over their support for the anti-government protests.

Is this a revolution in the making? Noam Chomsky sheds insight on this question and more in the exclusive interview below. Chomsky is institute professor emeritus in the department of linguistics and philosophy at MIT and laureate professor of linguistics and Agnese Nelms Haury Chair in the Program in Environment and Social Justice at the University of Arizona. One of the world’s most-cited scholars and a public intellectual regarded by millions of people as a national and international treasure, Chomsky has published more than 150 books in linguistics, political and social thought, political economy, media studies, U.S. foreign policy and world affairs. His latest books are The Secrets of Words (with Andrea Moro; MIT Press, 2022); The Withdrawal: Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan, and the Fragility of U.S. Power (with Vijay Prashad; The New Press, 2022); and The Precipice: Neoliberalism, the Pandemic and the Urgent Need for Social Change (with C.J. Polychroniou; Haymarket Books, 2021).

C.J. Polychroniou: Noam, Iranian women started these protests over the government’s Islamic policies, especially those around dress codes, but the protests seem now to be about overall reform failures on the part of the regime. The state of the economy, which is in a downward spiral, also seems to be one of the forces sending people into the streets with demands for change. In fact, teachers, shopkeepers and workers across industries have engaged in sit-down strikes and walkouts, respectively, amid the ongoing protests. Moreover, there seems to be unity between different ethnic subgroups that share public anger over the regime, which may be the first time that this has happened since the rise of the Islamic Republic. Does this description of what’s happening in Iran in connection with the protests sound fairly accurate to you? If so, is it also valid to speak of a revolution in the making?

Noam Chomsky: It sounds accurate to me, though it may go too far in speaking of a revolution in the making.

What’s happening is quite remarkable, in scale and intensity and particularly in the courage and defiance in the face of brutal repression. It is also remarkable in the prominent leadership role of women, particularly young women.

The term “leadership” may be misleading. The uprising seems to be leaderless, also without clearly articulated broader goals or platform apart from overthrowing a hated regime. On that matter words of caution are in order. We have very little information about public opinion in Iran, particularly about attitudes in the rural areas, where support for the clerical regime and its authoritarian practice may be much stronger.

Regime repression has been much harsher in the areas of Iran populated by Kurdish and Baluchi ethnic minorities. It’s generally recognized that much will depend on how Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei will react. Those familiar with his record anticipate that his reaction will be colored by his own experience in the resistance that overthrew the Shah in 1979. He may well share the view of U.S. and Israeli hawks that if the Shah had been more forceful, and had not vacillated, he could have suppressed the protests by violence. Israel’s de facto Ambassador to Iran, Uri Lubrani, expressed their attitude clearly at the time: “I very strongly believe that Tehran can be taken over by a very relatively small force, determined, ruthless, cruel. I mean the men who would lead that force will have to be emotionally geared to the possibility that they’d have to kill ten thousand people.”

Similar views were expressed by former CIA director Richard Helms, Carter high Pentagon official Robert Komer, and other hard-liners. It is speculated that Khamenei will adopt a similar stance, ordering considerably more violent repression if the protests proceed.

As to the effects, we can only speculate with little confidence.

In the West, the protests are widely interpreted as part of a continuous struggle for a secular, democratic Iran but with complete omission of the fact that the current revolutionary forces in Iran are opposing not only the reactionary government in Tehran but also neoliberal capitalism and the hegemony of the U.S. The Iranian government, on the other hand, which is using brutal tactics to disperse demonstrations across the country, is blaming the protests on “foreign hands.” To what extent should we expect to see interaction of foreign powers with domestic forces in Iran? After all, such interaction played a major role in the shaping and fate of the protests that erupted in the Arab world in 2010 and 2011.

There can hardly be any doubt that the U.S. will provide support for efforts to undermine the regime, which has been a prime enemy since 1979, when the U.S.-backed tyrant who was re-installed by the U.S. by a military coup in 1953 was overthrown in a popular uprising. The U.S. at once gave strong support to its then-friend Saddam Hussein in his murderous assault against Iran, finally intervening directly to ensure Iran’s virtual capitulation, an experience not forgotten by Iranians, surely not by the ruling powers.

When the war ended, the U.S. imposed harsh sanctions on Iran. President Bush I — the statesman Bush — invited Iraqi nuclear engineers to the U.S. for advanced training in nuclear weapons development and sent a high-level delegation to assure Saddam of Washington’s strong support for him. All very serious threats to Iran.

Punishment of Iran has continued since and remains bipartisan policy, with little public debate. Britain, Iran’s traditional torturer before the U.S. displaced it in the 1953 coup that overthrew Iranian democracy, is likely, as usual, to trail obediently behind the U.S., perhaps other allies. Israel surely will do what it can to overthrow its archenemy since 1979 — previously a close ally under the Shah, though the intimate relations were clandestine.

Both the U.S. and the European Union imposed new sanctions on Iran over the crackdown on protests. Haven’t sanctions against Iran been counterproductive? In fact, don’t sanctioned regimes tend to become more authoritarian and repressive, with ordinary people being hurt much more than those in power?

We always have to ask: Counterproductive for whom? Sanctions do typically have the effect you describe and would be “counterproductive” if the announced goals — always noble and humane — had anything to do with the real ones. That’s rarely the case.

The sanctions have severely harmed the Iranian economy, incidentally causing enormous suffering. But that has been the U.S. goal for over 40 years. For Europe it’s a different matter. European business sees Iran as an opportunity for investment, trade and resource extraction, all blocked by the U.S. policy of crushing Iran.

The same in fact is true of corporate America. This is one of the rare and instructive cases — Cuba is another — where the short-term interests of the owners of the society are not “most peculiarly attended to” by the government they largely control (to borrow Adam Smith’s term for the usual practice). The government, in this case, pursues broader class interests, not tolerating “dangerous” independence of its will. That’s an important matter, which, in the case of Iran, goes back in some respects to Washington’s early interest in Iran in 1953. And in the case of Cuba goes back to its liberation in 1959.

One final question: What impact could the protests have across the Middle East?

It depends very much on the outcome, still up in the air. I don’t see much reason to expect a major effect, whatever the outcome. Shiite Iran is quite isolated in the largely Sunni region. The Sunni dictatorships of the Gulf are slightly mending fences with Iran, much to the displeasure of Washington, but they are hardly likely to be concerned with brutal repression, their own way of life.

A successful popular revolution would doubtless concern them and might “spread contagion,” as Kissingerian rhetoric puts it. But that remains too remote a contingency for now to allow much useful speculation.

Copyright © Truthout. May not be reprinted without permission.

C.J. Polychroniou is a political scientist/political economist, author, and journalist who has taught and worked in numerous universities and research centers in Europe and the United States. Currently, his main research interests are in U.S. politics and the political economy of the United States, European economic integration, globalization, climate change and environmental economics, and the deconstruction of neoliberalism’s politico-economic project. He is a regular contributor to Truthout as well as a member of Truthout’s Public Intellectual Project. He has published scores of books and over 1,000 articles which have appeared in a variety of journals, magazines, newspapers and popular news websites. Many of his publications have been translated into a multitude of different languages, including Arabic, Chinese, Croatian, Dutch, French, German, Greek, Italian, Japanese, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish and Turkish. His latest books are Optimism Over Despair: Noam Chomsky On Capitalism, Empire, and Social Change (2017); Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (with Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin as primary authors, 2020); The Precipice: Neoliberalism, the Pandemic, and the Urgent Need for Radical Change (an anthology of interviews with Noam Chomsky, 2021); and Economics and the Left: Interviews with Progressive Economists (2021).