Islamic State & The Artaudian Theatre Of Cruelty

Abstract

Intrigued by the idea that the Islamic State’s media is performing Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty, we questioned in this article whether Islamic State’s use of media does indeed compare to the hellish visions of the notorious French dramaturge, and consequently ask ourselves, if so, how we should interpret and give meaning to the eventual connection between two subjects that seem so far apart, and yet so close to each other: the Theatre of Cruelty and the gruesome religiously inspired videos of Islamic State.[i] The results of our analysis confirm significant parallels between the Theatre of Cruelty and the cruel videos of Islamic State. Considering the fact that the message of cruelty is central to many of their videos, we conclude that ‘Islamic State’s media productions indeed implement the characteristics underlying Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty.’ But what does all this mean? Cruelty and violence are indeed elements of human being’s nature. Humankind has to embody it in one way or the other, and from that perspective, it is much better to incorporate these darker sides of men in the metaphysical sphere. We are deliberately speaking here of humankind, irrespective of religious or ethnic background, because there are Westerners and Easterners that have learnt this dear lesson: acknowledging the dark side of men and expressing it in art.

Key words: # Islamic State # Artaud # Theatre # Propaganda # Cruelty # Hermeneutics # Interpretation

1 Introduction

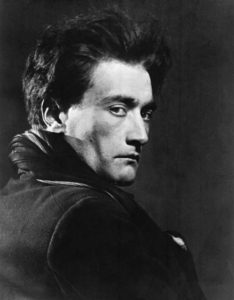

‘Artaud, a sickly child twisted further by the shock of World War I, wanted his actors to “assault the senses” of the audience, shocking parts of the psyche that other theatrical methods had failed to reach. Well, IS has read the book. It’s been obvious since September 11 that we’re living in an age of vicious political theatre. That’s what ‘terrorism’ is: the manipulation of large populations by shock and awe and ‘liberating unconscious emotions’’ (to quote Artaud).’[ii]

‘If the attacks on the Twin Towers used the iconography of the Hollywood action blockbuster, the beheadings in the desert evoke drama far more ancient – Old Testament strife, Hellenic legend. [..]It may sound unlikely, but ISIS is carrying out in extremis the program of the ‘Theatre of cruelty’ of the influential French dramaturgedemiurge Antonin Artaud.’[iii]

In the summer of 2014, the geopolitical stage was shaken by the Islamic State videos. Starting off a series of terrifying communiqués with a video of the beheading of journalist James Foley in A message to America, Islamic State quickly set a new standard for extremists’ use of media as a propaganda tool. Now that the extreme display of violence has become the hallmark of Islamic State terror, certain journalists have suggested a link between these brutal videos and dramatist Antonin Artaud (1896-1948) and his ‘Theatre of Cruelty’. We were intrigued by the idea that the correspondence between Islamic State’s media outlets and Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty might actually go beyond the shared predominance of cruelty and have taken the suggestion made by Sakurai as a cue to research whether Islamic State’s use of media does indeed compare to Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty on a more fundamental level. And consequently ask ourselves how, if so, we should interpret and give meaning to the eventual connection between two subjects that seem so far apart, and yet so close to each other: the Theatre of Cruelty and the gruesome religiously inspired videos of Islamic State.

The research done is comparative in nature. By comparing and contrasting the principal underlying ideas, the audience/performance relation, and the performance itself of Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty and Islamic State’s video productions, we hope to arrive at a detailed and nuanced understanding if and if yes, how Islamic State and Artaudian theatre relate to each other. The possible connection between both being eventually confirmed, we will consequently dwell on the meaning of such connection. Read more

Mati Shemoelof ~ …reisst die Mauern ein zwischen ‘uns’ und ‘ihnen’

Onlangs verscheen van dichter, auteur, uitgever, en bekende stem in de Arabisch-joodse Mizrahi-Beweging Mati Shemoelof …reisst die Mauern ein zwischen ‘uns’ und ‘ihnen’. Tekst en gedichten wisselen elkaar af.

Het heeft Mati Shemolof enige tijd gekost om te begrijpen dat de geschiedenis van zijn familie uit de geschiedenisboeken is verwijderd en in de Israëlische samenleving is gemarginaliseerd. Je komt in een soort van diaspora terecht als je van Arabische afkomst bent, terwijl Israël een thuis zou moeten zijn voor joden die naar een joodse staat emigreerden, aldus Shemoelof. Hij nam in 2007 dan ook het initiatief om Echoing Identies: Young Mizrahi Anthology uit te geven met teksten van de derde generatie Mizrachi. Door al zijn ervaringen is Mati Shemoelof zich bewust geworden van de diaspora van anderen, of het nu Syriërs zijn in Berlijn, Afghanen, Libiërs of Oost-Europeanen; maar vooral de diaspora van de Palestijnen uit de periode 1948 en 1967 raakt hem.

Shemoelof’s Perzische grootvader werd in het begin van de 20e eeuw gedwongen uit Mashhad (Iran) naar Haifa te emigreren, dat toen nog bij Palestina hoorde. Haifa van voor 1948 was een moderne stad, waar verschillende culturen vreedzaam naast elkaar leefden, waar zijn opa goed zaken kon doen en vrij was. Maar deze Palestijnse geschiedenis van Haifa is niet meer bekend.

De geschiedenis van zijn moeder is kenmerkend voor een familie van Mizrachim, voor joden met een Arabische cultuur en taal. Ze waren goed geïntegreerd in Irak en over het algemeen seculier. Zij werden echter in 1951 gedwongen van Bagdad naar Israël te emigreren, net als zo’n 120.000 andere Iraakse-joodse burgers, met achterlating van al hun bezit. Dat was onderdeel van de deal tussen Irak en Israël: de zionistische beweging kreeg arbeidskrachten en Irak bezit. Maar eerder had al de Farhud in Irak plaatsgevonden: op 1 en 2 juni 1941 vond een Pogrom plaats tegen joden in Bagdad, waarbij tussen de 150 en 200 doden vielen en van velen hun bezit werd afgenomen.

Nu zijn in Israël muren rondom Palestijnen, maar ook om de Arabische joden is een muur geplaatst. En toch zijn vele Mizrachi, die in armoede leven, niet solidair met de Palestijnen.

Om je te verhouden tot al die muren in Israël, in – en extern, is moeilijk en maakte Mati Shemoelof tot activist van de Mizrachi-Beweging, die strijdt voor sociale rechtvaardigheid en erkenning van identiteit. De Mizrachi-Beweging onderzoekt met name de verwantschap tussen hun identiteit en die van de Palestijnen en de Arabische wereld. Read more

Human Rights, State Sovereignty, And International Law

We live in an era where virtually every government on the planet claims to pay allegiance to human rights and respect for international law. Yet, violations of human rights and plain human decency continue to occur with disturbing frequency in many parts of the world, including many allegedly “democratic” countries such as the United States, Russia, and Israel. Indeed, Donald Trump’s immigration policy, Putin’s systematic repression of dissidents, and Israel’s abominable treatment of Palestinians seem to make a mockery of the principle of human rights. Is this because “faulty” forms of government or because of some Inherent tension between state sovereignty and human rights? And what about the international regime of human rights? How effective is it in protecting human rights? Richard Falk, a world renowned scholar of International Relations and International Law sheds light into these questions in the exclusive interview below with C. J. Polychroniou.

Richard Falk is Alfred G. Milbank Emeritus Professor of International Law, Politics, and International Affairs at Princeton University and the author of some 40 books and hundreds of academic articles and essays. Among his most recent books are A New Geopolitics (to be published in December 2018); Palestines’s Horizon: Toward a Just Peace (2017); Humanitarian Intervention and Legitimacy Wars: Seeking Justice in the 21st Century (2015); Chaos and Counterrevolution: After the Arab Spring (2014); and Path to Zero: Dialogues on Nuclear Dangers (2012).

C. J. Polychroniou: Richard, you taught International Law and International Affairs at Princeton University for nearly half a century. How has international law changed from the time you started out as a young scholar to the present?

Richard Falk: You pose an interesting question that I have not previously thought about, yet just asking it makes me realize that this was a serious oversight on my part. When I started thinking on my own about the role and relevance of international law during my early teaching experience in the mid-1950s, I was naively optimistic about the future, and without being very self-aware, I now understand that I assumed that moral trajectory that made the future work out to be an improvement on the past and present, that there was moral progress in collective behavior, including at the level of relations among sovereign states. I thought of the expanding role of international law as a major instrument for advancing progress toward a peaceful and equitable world, and endeavored in my writing to encourage the U.S. Government to align its foreign policy with international law, arguing, I suppose in a liberal vein, that such alignment would promote a better future for all while at the same time being beneficial of the United States, especially given the overriding interest in avoiding World War III.

My views gradually evolved in more critical and nuanced directions. As my interests turned toward the dynamics of decolonization, I came to appreciate that international law had legitimized European colonialism, and the exploitative arrangements that were imposed on the countries of the global south. I realized that the idealistic identification of international law with peace and justice was misleading, and at best only half of the story. International law was generated by the powerful to serve their interests, and was respected only so long as vital interests of these dominant states were not threatened.

The Vietnam War further influenced me to adopt a more cautious view of international law, and even more so, of the United Nations. I opposed the war from the outset from the perspective of international law, citing the most basic prohibitions on intervention in the internal affairs of sovereign states and the core prohibition of the UIN Charter against all recourses to aggressive force. I did find it useful to put the debate on Vietnam policy in a legal format as the country was then under the sway of liberal leadership, although tinged with Cold War geopolitics and ideology. The defenders of Vietnam policy, motivated by Cold War considerations, relied on legal apologetics as well as claims that it was important for world order to contain the expansion of Communist influence, and that the adversary in Vietnam was China rather than North Vietnam. The legal debate to which I devoted energy for ten years convinced me that international law on war/peace issues was subordinated to geopolitics including by the Western democracies, and that even so, legal counter-arguments were always available to governments eager to disguise their reliance on geopolitical priorities. International law remains useful and even necessary for the routine transnational activities of people and governments, stabilizing trade and investment relations, but often in ways that favor the rich, and issues pertaining to questions of safety, communications, and tourism exhibit a consistent adherence to an international law framework. Read more

Trump’s Economy Is On A Path To A Bust

Whose interests are being promoted by macroeconomic policies in the United States? Is Donald Trump good for the economy? Is he responsible for the current economic indicators, which seem to be healthy? Are his tariff policies good for workers here and abroad? And how does his approach to economics differ from Obamas?

Whose interests are being promoted by macroeconomic policies in the United States? Is Donald Trump good for the economy? Is he responsible for the current economic indicators, which seem to be healthy? Are his tariff policies good for workers here and abroad? And how does his approach to economics differ from Obamas?

Howard Sherman is Emeritus Professor of Economics at the University of California at Riverside, a founding member of the Union for Radical Political Economics and author of Inequality, Boom, and Bust: From Billionaire Capitalism to Equality and Full Employment and Principles of Macroeconomics: Activist vs Austerity Policies (co-authored with Michael Meeropol, and now in its second edition). In an exclusive interview for Truthout, Sherman provides answers to these questions and exposes the myths associated with the “success story” of Trumps economy. In fact, Sherman contends that the US economy is on the verge of an economic recession and possibly a Great Depression.

C. J. Polychroniou: Howard, what are the goals and aims of macroeconomic policy in the US, and what interests are they designed to protect and promote?

Howard Sherman: There are two different views in the US over macroeconomic policy. One is the conservative view, which says that capitalism is the best possible economic system, so it needs no reforms, or just a few minor ones. Capitalism functions smoothly and there is a recession only when there is an incorrect government policy. Furthermore, there is never too much inequality because inequality merely reflects the productivity of an individual, so no reform is needed to change inequality.

The second view is the progressive economics view, held by a minority. In general, progressives believe that inequality represents extremely high profits made by corporations that exploit the labor of workers at low wages. Inequality increases with every capitalist expansion, meaning that there is an increase in the ratio of all profits to all wages. Moreover, this increase in inequality means that the demand for goods and services by workers, based on their wages and salary, is limited. As such, the rising supply of goods to the market far outdistances the demand for these goods by the entire working population. The result is an economic recession or a depression that produces heavy unemployment in every downturn business cycle.

The conservative view that capitalism is near perfect helps to prevent reforms of the system, so it makes the wealthy owners very happy. On the other hand, the progressive policy that is necessary to raise wages and salary reflects the views of the great majority of the working population. Read more

David Pinto & Paul Cliteur (red.) ~ Moord op Spinoza – De opstand tegen de Verlichting en moderniteit

David Pinto en Paul Cliteur nodigden gelijkgestemde auteurs uit een persoonlijke bijdrage te leveren aan de bundel ‘Moord op Spinoza’. Het modernistisch wereldbeeld staat onder druk, bijna wekelijks vindt er wel een aanslag plaats die wordt opgeëist door ISIL of een ander islamitisch-terroristische groepering. Die aanslagen worden gemotiveerd door de terroristen zelf onder verwijzing naar een premodern, maar specifiek ‘theoterroristich’ wereldbeeld. Zij spreken in negatieve termen over democratie en willen die vervangen door een theocratie.

Zij bekritiseren individuele rechten van de mens en komen op voor de rechten van Allah. Europese politici weten niet wat te doen terwijl “multiculturalisten, policoristen en postmodernisten” partij kiezen tegen westerse waarden die als ’koloniaal’, ‘kapitalistisch’, ‘arrogant’ of ‘eurocentrisch’ worden ‘gedeconstrueerd, aldus Cliteur en Pinto. Kan de moord op de Verlichting nog worden gestopt?

Het eerste essay Dubbel Clash: religieus en cultureel – De botsing tussen moderne en premoderne waarden is geschreven door hoogleraar interculturele communicatie David Pinto, geboren en getogen in een klein berberstadje aan de Hoge Atlas in Marokko, kind van joods orthodoxe analfabetische ouders. Hij onderzoekt hoe het kan dat mensen zo verschillen wat betreft waarden, normen, communicatie, gedrag, perceptie en beleving. Hij heeft daartoe een fijnmazig structuurtheorie ontwikkeld. Pinto concludeert dat de botsing tussen het waardenstelsel van hedendaagse vluchtelingen en migranten van het Westen niet

slechts ligt bij religie maar ook bij cultuur. Men erkent het probleem niet en de migranten worden te weinig uitgedaagd zich aan te passen. De grote fout van de linkse denkers is dat zij vanuit de westerse notie van gelijkwaardigheid denken. De bedreiging is slechts te stoppen door het probleem zonder angst te onderkennen, voor de volle 100 procent voor de verworven Verlichting en moderniteit te gaan – dus bijvoorbeeld geen gescheiden zwemmen voor vrouwen en mannen toestaan en ophouden met paternalisme. Hierbij passende maatregelen moeten worden getroffen.

Voor jurist en filosoof Paul Cliteur is de inpassing, de accommodatie van religie binnen het politieke kader van de moderniteit problematisch, waarbij het moderne politieke wereldbeeld zich laat leiden door democratie, rechtsstaat en mensenrechten. Hij schetst in zijn bijdrage Moderniteit en premoderniteit in de staatstheorie & de moord op Spinoza vijf modellen voor de verhouding staat en religie. De premoderne modellen van Politiek atheïsme (staat verbiedt godsdiensten) en Theocratie (staat steunt één specifieke godsdienst) en de moderne modellen van Staatsgodsdienst (staat kiest één religie als leidend voor de staat, maar wel met keuzevrijheid aan het individu), Multiculturalisme (staat ondersteunt alle godsdiensten), en als vijfde model Laïcité (secularisme, staat beschermt slechts de individuele keuze voor godsdienst). Voor Cliteur is secularisme het enige model dat rechtdoet aan de democratie en dat moeten we verdedigen. Het Westen is in de ban van de religie van ontkenning: elke relatie tussen radicalisering en het radicaal gedachtegoed wordt ontkend, aldus Cliteur. Meebuigen is echter geen oplossing: multiculturalisme is suïcidaal. Read more

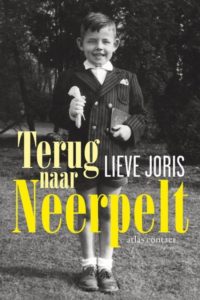

Lieve Joris ~ Terug naar Neerpelt

“Net als de grote puzzel waar ik als kind op winteravonden in bomma’s opkamer aan werkte; uiteindelijk kwam er altijd weer een intacte oceaanstomer tevoorschijn en werden de blauwe en grijze puzzelstukjes zee en lucht.”

“Net als de grote puzzel waar ik als kind op winteravonden in bomma’s opkamer aan werkte; uiteindelijk kwam er altijd weer een intacte oceaanstomer tevoorschijn en werden de blauwe en grijze puzzelstukjes zee en lucht.”

Lieve Joris nam ons in de voorbije jaren mee naar Damascus, naar Mali, naar Congo, naar Guangzhou en naar al die andere landen, steden en dorpen. Door haar hoofdpersonen met milde blik te portretteren kregen de grote gebeurtenissen in de wereld een menselijke maat.

Naast die welwillende blik zorgde ook haar rustige en elegante stijl voor aangename uren. Nergens laat een zin of een alinea je struikelen.

Ruim dertig jaar geleden verscheen Terug naar Congo. Congo was het land van heerom, nonk Albert. Eens in de drie jaar kwam heerom met verlof naar Vlaanderen. En vertelde hij over zijn leven daar in dat donkere land. De kleine Lieve luisterde ademloos.

En nu is er Terug naar Neerpelt. Het verhaal van de familie Joris. Een familie die getroffen is door iets dat “groter was dan wij, hier waren we niet tegen opgewassen.”

Het aandoenlijke jongetje op de omslag is broer Fonny. Fonny, de grote broer waar de jonge Lieve naar opkeek. De broer die alles kon en durfde.

Maar ook de broer die door zijn verslaving het gezin Joris meesleepte in een draaikolk van emoties.

Terug naar Neerpelt is meer dan het verslag van een gezinsdrama. Het is ook een reis door het Vlaamse platteland in de jaren vijftig en zestig. Het verhaal van de ontdekking dat buiten het dorp een grote wereld ligt. Van Onze-Lieve-Vrouw van het Heilig Hart van Averbode naar Leonard Cohen, van het beeldje van de Heilige Antonius van Padua naar Bob Dylan.

De kinderen Joris kunnen gerust zijn.

Hun zus heeft het boek, hoe zou het ook anders kunnen, met mededogen geschreven. Mededogen met Fonny, maar ook met ieder gezinslid op zich.

Al leek het in al die jaren vaak dat de rampspoed ‘groter was dan wij’, Lieve Joris zorgt er met dit boek voor dat alles weer op zijn plek kan vallen. Zo worden de blauwe en grijze puzzelstukjes weer zee en lucht.

—

Lieve Joris – Terug naar Neerpelt. Atlas Contact, Amsterdam. 2018. ISBN 9789045037165