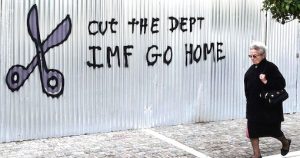

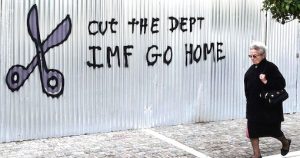

Photo: occupy.com

For the last several months, Greece’s international creditors – the European Union (EU) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) – had been at a standoff over debt relief, budget targets and various reforms, including taxes and pensions, thereby delaying the completion of a long overdue bailout review that should have been done in October 2016. The standoff added extra pressures to an economy that has been in recession for eight straight years, and even revived fears of a “Grexit” as bank runs had returned in full steam. In the meantime, the Syriza-led government of Alexis Tsipras was playing the role of a mere observer in a tug-of-war between two institutions that are in full control of the country’s finances, and merely trying to accommodate the demands of both sides.

Since the start of the current financial and economic crisis in Greece, which goes back to 2008 (although the actual outbreak of the debt crisis occurs in early 2010), the country’s GDP has shrunk by about 26 percent. Unemployment jumped to as high as 28 percent in 2013, and has now stabilized at 23 percent, but more than 42 percent of the population has “dropped below the poverty threshold of 2005.”

This harsh reality is the price the country is paying for its fiscal derailment as a member of a currency union (the euro) and the imposition of three consecutive bailout programs by the EU and the IMF. These bailouts have been accompanied by draconian measures of fiscal consolidation (austerity) and a radical neoliberal agenda which includes sharp cuts in wages, salaries and pensions, liberalization of the labor market and blanket privatization.

From the beginning, the bailout plans were never intended to rescue the Greek economy, but rather to avoid a financial meltdown on the continent, as several European banks had recklessly loaned to the public sector since Greece adopted the euro in 2001. Indeed, virtually all of the funds that have been provided to Greece since 2010 have gone towards the repayment of international loans – first to the European banks, and then to the country’s official creditors – rather than towards the economy.

But let’s return to the present: the standoff between EU and IMF over the “best way” to deal with Greece’s current financial and economic catastrophe, which finally came to an end a couple of weeks ago, with the Greek government agreeing to a new round of austerity measures which amount, essentially, to a fourth memorandum.

Spreading False Hopes About Recovery and Vague Promises About Debt Relief

Having grossly miscalculated the impact of the fiscal policies it proposed on the Greek economy, the IMF has been extremely reluctant to join in the third bailout program (agreed to and signed by the pseudo-leftist Syriza government of Alexis Tsipras), sensing that Greece will never be able to repay its loans. The country is essentially bankrupt, and the prospects for a return to the private credit markets any time soon are not very promising, as there are no signs of recovery on the horizon. At some point, small rates of growth will inevitably be registered solely because of the economy having hit rock bottom, but this is not the case at present.

Still, illusions of a recovery have been the hallmark of both the Syriza government and of the conservative government that preceded it. But this should not be surprising. Spreading false hopes to the citizens of a bankrupt nation that has lost its sovereignty is the last refuge of political scoundrels, of governments and their officials who have opted to become lackeys of the international elite rather than lead their people to resistance and to the overthrow of financial regimes imposing debt bondage.

Indeed, for the last few months, senior-level officials in the Syriza government, such as Minister of Economy and Development Dimitri B. Papadimitriou, were propounding that growth had made a comeback and that the crisis was over before the official statistics for the fourth quarter of 2016 were finally released in early March 2017. However, those figures showed the Greek economy had contracted again by 1.2 percent.

Read more

Gerald Epstein is Professor of Economics and a founding Co-Director of the Political Economy Research Institute (PERI) at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

With Donald Trump in power, US society is likely to witness in the next four years a regression of social progress and environmental damage unlike anything the country has seen in the course of its modern history. In this context, progressives have their hands full and only massive resistance may halt the march to the precipice. But any effective strategy of resistance requires linking theory and praxis. It is imperative that we understand the dynamics in US society that brought Trump to power. It is imperative that we also understand what Trump actually represents and whether Trumpism is here to stay. Then we can think of the most effective ways to challenge the sort of political gestalt in Trump’s miasma.

In this exclusive interview, radical political economist Gerald Epstein addresses these issues and offers his insights on how we can resist Trumpism. Gerald Epstein is professor of economics and co-director of the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, and author of scores of books and articles on the political economy of contemporary capitalism.

C.J. Polychroniou: The rise of Donald Trump to power took a lot of people by surprise, although there were strong indications for a long time now that the conditions in the United States were ripe for the emergence of an authoritarian leader. Still, the actual reasons for the rise of a fake populist in power remain rather puzzling, so I’d like to start by asking for your views on what led to Trump’s stunning victory.

Gerald Epstein: As you say, conditions of working people have been deteriorating in the US for many decades now, creating fertile ground for leaders outside the political establishment to offer anti-elitist explanations and offer apparent solutions for people desperate for them. This helps to explain both the Bernie [Sanders] and the Trump phenomena. But when you add on top of these the deep racist, sexist and xenophobic undercurrents that have always been present in American society and which are low-hanging fruit just waiting to be picked and utilized by a demagogue, you have Donald Trump…. In short, the Democratic Party’s embrace of neoliberalism, which continued with Hillary Clinton, is a big part of the story. Still, one should not forget the devastating roles that the Republican Party played in the last eight years as they gained more and more power — not just in Congress, but also in state and local governments in many parts of the country. They were able to do this by exploiting Democratic failures, but also by a money-fueled long-term strategy by extreme right-wing capitalists, such as the Koch brothers and others. Without this massive financial input and a long-term strategy, this victory would not have occurred. More specifically, their electoral strategy in the last four to eight years … was to incapacitate the government from helping poor and working-class people, while enriching the powerful and the elite — and then blame the Democrats for the fall out. Sam Brownback, governor of Kansas, and Scott Brown, governor of Wisconsin, as well as the Republican Party in Congress in Washington, DC, pursued this seemingly kamikaze approach to governing. Amazingly, it succeeded. It shoved poor and working people more and more into the dirt as cuts were made to public investments, benefits, living standards. But rather than blaming the Republicans, many of these Americans voted against the Democrat — Hillary Clinton.

This means that only a very weak party (the Democrats), a very weak candidate (Hillary Clinton) and a huge amount of luck — the rise of Trump, [former] FBI Director James Comey’s last-minute attack on Clinton and an Electoral College system that delivered the presidency to Trump despite losing the vote by 3 million votes — could have ultimately ended in Trump’s victory. But the fact that he would have gotten so close even without these intervening factors underlines the deep rot in the system, including the Democratic Party’s neoliberalism and the role of massive amounts of right-wing money combined with a long-term, revolutionary political strategy.

But to see the real underlying causes of Trumpism, we have to dig a bit deeper. All of the above is taking place in a context of a 30- to 40-year transformation of the US’s place in the global economy — a transformation that would have required an economic policy directed toward managing it for the working classes and the poor, rather than for finance and the elite, which is what happened as I described earlier. The relative decline of the US as a site of production, the rise first of Japan, China, India and other countries in the developing world, and the intermittent competition with Europe and other countries meant that the economic institutions that the US relied on in the early post-World War II era could no longer deliver the goods to both working-class Americans and the capitalists. The Democrats and Republicans both went with the capitalists and a neoliberal faith in markets, rather than engaging in the reshaping of US institutions to thrive in a more competitive global environment. The mixture of financialization and subsidized support for US multinational corporations, and all kinds of free rides for elites, ultimately brought us to the age of Trumpism.

Read more

Prof. Fatima Suleman

On 16 May Prof. Fatima Suleman gave her inaugural lecture as the new Professor to the Prince Claus Chair in Development and Equity at Utrecht University, entitled: Affordability and equitable access to (bio)therapeutics for public health. Prof. Suleman works at the University of Kwazulu Natal in South Africa and connects the theme of development and equity with accessibility of medicine, pharmacy and health economics.Read the highly interesting text of the inaugural lecture or watch the video of the livestream!

- by: C.J. Polychroniou & Marcus Rolle

Robert Pollin ~ Photo: UMass Amherst

Donald Trump will probably go down in history as having pulled the biggest political con job in US electoral politics. With no coherent ideology but lies and false promises, he managed to win the support of millions of white working-class people whose lives have been shattered by globalization and stagnant wages. In an exclusive interview for Truthout, Robert Pollin, professor of economics and co-director of the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, puts into context Trump’s stance on globalization and his “America first” stance.

C.J. Polychroniou and Marcus Rolle: Resistance to globalization was the preeminent policy theme in Trump’s election campaign, as he not only attacked immigration and promised to build a wall on the US-Mexican border, but rallied against existing trade agreements, including the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and promised to withdraw the US from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade deal, a promise he carried out immediately upon entering the White House. Given that the US remains the world’s only true superpower and that multilateral trade agreements constitute an integral component of the global neoliberal economy, where, firstly, does resistance to globalization locate Donald Trump on the politico-ideological spectrum and, secondly, what is, in your view, his ultimate vision for the United States?

Robert Pollin: Donald Trump is difficult, if not impossible, to locate with respect to the global neoliberal project; first of all because all evidence thus far supports the conclusion that he has no real convictions at all, other than self-promotion. It’s true that he campaigned on a strong nationalist agenda that diverged in many ways from neoliberalism — i.e. from a program of free trade, unregulated financial markets and freedom for multinational corporations to operate as they please. That program did speak to the experiences of the US white working class, which, as even former Federal Reserve Chair Alan Greenspan recognized in the 1990s, had become “traumatized” by the forces of neoliberal globalization. It is unclear how forcefully Trump intends to diverge from neoliberalism in practice, despite his rhetorical appeals to his base within the US white working class. To me, relative to understanding Donald Trump’s “ultimate vision,” I think it is much more important for progressives to become much clearer in defining our own vision on globalization. Specifically, in my view, what is most important is establishing a clear distinction between neoliberal globalization and globalization in any form at all.

Neoliberal globalization is all about creating freedom for private capital and financial speculation, which in turn has created an unprecedented global “reserve army of labor,” to use Marx’s brilliant turn of phrase. The global reserve army of labor has indeed pitted US workers against workers in China, India, Kenya, Mexico, Guatemala — you name it. This has weakened workers’ bargaining power in the US, which in turn is the most basic factor driving wage stagnation in the United States for the past 40 years, even as US average labor productivity has more than doubled over this period. But we should be able to envision an alternative framework in which the US and other countries are open to trade and immigration within a context of a commitment to full employment and a strong social welfare state. Within a full employment economy with strong social protections, an open trading system will not produce a global reserve army of labor to anything close to the extent we have experienced over the past 40 years. This is the key point.

Read more

On the occasion of the international conference ‘Education for Life in Africa’, organized by the Netherlands Association for Africa Studies in The Hague on 19 and 20 May 2017, the ASCL Library has compiled a web dossier on this theme. The conference is dedicated to Goal 4 of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): ‘Ensure inclusive and quality education for all and promote lifelong learning’.

On the occasion of the international conference ‘Education for Life in Africa’, organized by the Netherlands Association for Africa Studies in The Hague on 19 and 20 May 2017, the ASCL Library has compiled a web dossier on this theme. The conference is dedicated to Goal 4 of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): ‘Ensure inclusive and quality education for all and promote lifelong learning’.

The web dossier contains recent titles from our Library catalogue (from 2013 onwards), divided into six thematic sections. Each title links to the corresponding record in the online catalogue, which provides abstracts and full-text links (when available). The dossier also contains a number of relevant websites. African textbooks present in our Library (for example, on history and on religion), have not been included in this web dossier. They can be searched in our catalogue using the keyword textbooks (form) combined with a keyword such as ‘history’, ‘Islam’ or ‘Christianity’.

The dossier is introduced by Dr Akiiki Babyesiza, an expert in higher education, specializing in Sub-Saharan Africa. Dr Babyesiza has been working for CHE Consult (Berlin), a consulting company in the field of strategic higher education management, since May 2017.

Introduction

Africa is the youngest continent, with half of its population under the age of 15. An inclusive and equitable education sector from pre-primary to higher education that can offer opportunities for this rising young population is at the core of the targets of Sustainable Development Goal 4: Ensure inclusive and quality education for all and promote lifelong learning.

In recent decades, the multilateral initiative Education for All and the education related goals of the Millennium Development Goals have led to substantial changes in the field of education in Africa. Yet, the goal of universal primary education has not been achieved and a high proportion of the world’s out-of-school children are African. While access to primary, secondary and higher education has increased, many other challenges persist with respect to equity and quality. Some of the challenges are connected to how and what children learn at school. One important aspect is the language of instruction, which is usually not the pupils’ mother tongue. Often, the lack of educational success is connected to a lack of proficiency in the language of instruction. Another issue is the role of pedagogy and whether students learn to apply knowledge or just to repeat it. This is, of course, also connected to the quality of the education and training of teachers. Moreover, inequities remain between rural and urban areas with respect to the distribution of schools, particularly secondary schools and higher education institutions. And there are inequities with regard to gender, ethnicity, disability and refugee status.

These challenges are exacerbated in situations of war and violent conflict, where educational institutions can worsen as well as mitigate conflict. Students can be marginalized by language, teaching content and the politicization of teaching staff. At the same time, educational institutions that offer peace and civic education for students and accelerated learning programmes for former child soldiers can have a positive impact in post-conflict situations.

Whether in times of war or in times of peace, there is need for a more holistic view of education – from pre-primary education to higher education and technical vocational education and training. The higher education sector, for example, has long suffered from neglect due to the strong focus on primary education in international development debates. Due to the social rates of return theory adopted by the World Bank, higher education institutions in Africa were perceived as an unnecessary luxury. These days, politicians and development actors have embraced the interconnectedness of the different educational sectors. Teachers are taught at higher education institutions, so there cannot be successful primary and secondary schools without quality tertiary education. While the number of higher education students in Sub-Saharan Africa doubled between 2000 and 2010, the rate of youth enrolled in higher education is only around 6% (26% is the global average). Furthermore, many scholars, practitioners and politicians believe that the development of a knowledge economy/society, with higher education institutions at its centre, is key to local and global sustainable development.

Access to education and enrolment: http://www.ascleiden.nl/content/education-life ~ scroll down a little for the web dossier.

Karl Marx (1818-1883) Ills.: Ingrid Bouws

Over the years, especially following the latest global financial crisis that erupted in late 2007, there has been a renewed interest in the work of Karl Marx. Indeed, Marx remains essential for understanding capitalism, but his political project continues to produce conflicting interpretations. What really motivated Marx to undertake a massive study of the laws of the capitalist mode of production? Was Marx interested in liberty, or merely in equality? And did Marx’s vision of communism have any links to “actually existing socialism” (i.e., the socialist regimes of the former Soviet Union and the Eastern bloc)?

Marx’s Inferno: The Political Theory of Capital, a recently published book by McGill University Professor William Clare Roberts, offers a rigorous and unique interpretation of Marx’s political and philosophical project. The book reveals why Marx remains extremely relevant today to all those seeking to challenge capitalism’s domination and violence — from its exploitation of labor power to the use of oppressive stage apparatuses as reflected in the exercise of police brutality. We spoke to William Clare Roberts about Marx’s project and vision of communism.

C.J. Polychroniou: In your recently published book Marx’s Inferno, you contend that liberty, rather than equality, was Marx’s primary politico-philosophical concern and, subsequently, claim that his work and discourse belong in the republican tradition of political thought. Can you elaborate a bit on these claims and tell us how they are derived from a particular reading of Marx’s work?

William Clare Roberts: I would say it a bit differently. Marx is certainly concerned with equality. Everyone on the left is. The question is: equality of what? This is where freedom, or liberty, comes in. In my book, I argue that Marx shared the radical republican project of securing universal equal freedom. When we talk about equality on the left today, this is too often assumed to mean equality of material wealth or equality of treatment, such that economic equality is the goal in itself. For Marx, economic inequality was not the main problem. It was a consequence and a breeding ground of domination. This was Marx’s prime concern.

To be dominated is to be subject to the whims or caprice of others, to have no control over whether or not they interfere with you, your life, your actions, your body. Republicans, going back to the Roman republic, have recognized that this lack of control over how others treat you is, of itself, inimical to human flourishing. [According to their philosophy], whether or not the powerful actually hurt you is actually less important than the fact that they have the power to hurt you, and you can’t control whether or not or how they use that power. It is in this space of uncertainty and fear that power does its work. So, for example, that an employer can fire a worker at will is usually enough to secure the worker’s obedience, especially where the worker doesn’t have many alternative sources of income. Likewise, that the police have the basically unchecked power to arrest, beat and harass people in many neighborhoods produces all manner of distortions in how people live, regardless of whether they have actually been beaten or harassed. To live free is to live without this fear or this need to watch out for the powerful. And this means being equally empowered.

Traditionally, republicans were concerned only to protect the freedom of a certain class of men within their own political community. In the 19th century, however, workers, women, escaped slaves — people who lived with domination — began to take over this republican theory of freedom and to insist that everyone should enjoy equal freedom. I read Marx as part of this tradition.

Marx’s major innovation in this tradition was to develop a theory of the capitalist economy as a system of domination. Radicals then — like many radicals today — assimilated capital to previous forms of power — military, feudal, or extortionary. They saw the capitalist simply as a monopolist, and the government as the enforcement squad of the monopolists. To Marx, this was insufficient as a critical diagnosis. The capitalists are, like the workers, dependent upon the market. They must act as they do or be replaced by other, more effective capitalists. Marx saw in this market dependence a new sort of all-round social domination. The livelihood of each depends upon the unpredictable and uncontrollable decisions of many others. This impersonal domination mediates and transforms the other forms of domination people experience.

Read more