ISSA Proceedings 2002 – Perelman On Causal Arguments: The Argument Of Waste

Introduction

Introduction

The main aim of this paper cannot be a detailed treatment of the concept of ”causality”. Nor can I deal with all types of causal arguments distinguished by Chaim Perelman and Lucie Olbrechts-Tyteca in their ”Nouvelle Rhétorique”(i) . Therefore, after a few more general remarks on causality (section 1) and Perelman’s treatment of causal arguments (section 2) I wish to focus on a specific causal argument within Perelman’s typology, namely, the ”Argument of Waste” (= AoW)(section 3).

1. On Causality

There is no doubt that causality is a concept of fundamental importance for all types of argumentative discourse. Without being able to deal with the complexities of this concept (for recent detailed treatments cf. e.g. Tooley 1987, Pearl 2000, Meixner 2001), I would like to consider the following features as collectively defining the everyday concept of causality (cf. also Schellens, 1985, 82f.; Kienpointner, 1992, 328ff. for a more detailed discussion):

Event A is the cause of event B if and only if

1. B regularly follows A

2. A occurs earlier than (or at the same time as) B

3. A is changeable/could be changed

4. If A would not occur, B would not occur (ceteris paribus)

If an event A fulfils criteria 1- 4, it is the ”Cause” of event B, which in turn can be called the ”Effect” of A. This definition has to be supplemented with further concepts in order to prevent a reductionist view of causality. First of all, and most of the time, there is not one and only one ”Cause A” leading to one ”Effect B”, so you have to take into account that single causes are rarely necessary AND sufficient conditions for single effects (Meixner, 2000, 219ff. provides a critical overview of theories which characterize causality as a relationship based on 1. necessary conditions or 2. necessary and sufficient conditions or 3. probability or 4. nomological regularities, respectively). Moreover, argumentative discourse often has to take into account not only the immediate cause A of effect B, but also the indirect causes A1…ⁿ of B and the indirect effects B1…ⁿ of A as elements of a longer chain or sequence of causes and effects.

Furthermore, the actions of human agents cannot be reduced to causal sequences of events (cf. Meixner, 2001, 320ff.). Even in cases where the actions of human agents cause certain reactions by other human beings quite regularly, or where human actions are motivated by similar ends quite regularly (cf. criterion 1), important differences between human actions and ”natural” causes and effects remain. Persons belonging to certain (subgroups of) cultures can choose to react in different ways following differing cultural patterns of conscious and purposeful behaviour. Moreover, they can also refrain from acting (cf. Meixner, 2001, 331ff.). It is true that these choices can be severely limited by physical, psychological and/or socio-economic constraints, but they are almost never strictly determined in the way apples, pears or oranges are determined to fall from a tree by the laws of gravitation. Furthermore, one and the same action can be motivated by differing underlying incentives (emotions, feelings, beliefs) of the agents, whose actions are neither strictly determined by each single incentive nor by all of them taken together. Read more

ISSA Proceedings 2002 – Mapping Visual Narrative As Argument In Interactive Media

Introduction

Introduction

History, art, and science are a few areas of study whose knowledge is regularly delivered through informal educational settings (Bloom and Powell, 1984), particularly in museums. Carrying out one of the primary missions for most museums, to educate its audience, individual installations must be designed to accurately convey a clearly specified body of information, within a limited timeframe to a diverse, often international audience. Two major concerns drive design: First, designers and content experts are usually most concerned that the information conveyed through the installation is accurate and understandable to the audience. Key concepts and relationships among related factors in the particular topic area must be clear to primarily non-expert audiences. In addition to these basic information design considerations, designers are also well aware that the audience’s engagement with an installation is voluntary, and the installation typically competes for the museum goer’s engagement with the other activities, displays, special shows and installations offered by the museum. Marketing experts typically consider a museum’s target audience to be primarily recreational audiences – the same population choosing among a variety of leisure-time activities, including professional sports, movies, family parks, and so on. Even museums targeting children, in which cases the educational purposes are pointed, concern themselves with making the museum experience larger and more eventful than learning in the classroom setting. For reasons of attendance and funding, museums take seriously the entertainment factor in any installation. Thus, designers of museum installations are quite concerned with attracting and maintaining a visitor’s attention in order to impart the intended historical, artistic, or scientific knowledge.

The specific role that visual elements contribute to a user’s grasp of a narrative conveyed through multimedia technology is not fully explored, but research has been conducted in many diverse areas, including textual narrative in literature (Nodelman, 1988; Witek, 1989; Sillars, 1995), visual narrative in art (Holliday, 1993; Kupfer, 1993; Lewis, 1999), narrative as cognitive framework (Bruner, 1991; Beloff, 1994; Graesser, 1981), and as a rhetorical act (Voss, Wiley, & Sandak, 1999) in psychology, as a logical guide in the designed world (Buchanan,1989), and as a networking and logical model in computer science (Bers and Cassell, 2000; Sengers, 2000; Dautenhahn, 2001).

Aristotle (Kennedy, 1991) identifies the narrative as one of two types of argument, the other one being the enthymeme. Generally, a narrative can be understood to consist of the following:

– a context from which the narrative emerges: a beginning point in time, space, or condition

– a sequence of actions performed by agents (characters) which move the story towards a culminating point

– an ending, closure point, denouement Read more

ISSA Proceedings 2002 – Dissociation And Its Relation To Theory Of Argument

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

According to Chaim Perelman and Lucie Olbrechts-Tyteca (1969, 190), association and dissociation are the two schemes of argument. While argumentation scholars have researched association through the study of analogy, causal arguments, and arguments from authority, to name a few, they have not conducted so much research on dissociation. Given this situation, study on dissociation is urgently needed. In section 2 of this paper I will offer a short description of dissociation from what Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca stated. In section 3, I will lay out some issues surrounding dissociation that should be dealt with. In section 4, I will redeem dissociation as a scheme of argument by replying to the issues raised in section 3. Section 5 is the conclusion.

2. Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca on dissociation

Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca classified argumentation schemes into association and dissociation. In association, an arguer assembles what are thought to be different into a unity. Examples of association are causal arguments, and arguments from authority. In dissociation, an arguer dissembles what are originally thought to be a single entity into two different entities, by introducing some criteria for differentiation (1969, 190). Using dissociation, the arguer creates a new vision of the world, and persuades her or his audience to accept it. If the audience accepts the new vision offered by dissociation, then a new reality will be established. In short, dissociation attempts to establish a conceptual demarcation in what is believed to be a single and united thing.

3. Dialectical materials surrounding the conception of dissociation

Although Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca advanced a claim that dissociation is an argumentation scheme, argumentation scholars have questioned their claim for different reasons. One argument denies the claim that dissociation is a scheme, and another advances a claim that it is a technique. Still others address its less systematic nature and its dubious presuppositions. These arguments constitute dialectical material in Ralph H. Johnson’s sense (2000b, p.7). In other words, they are objections, alternative positions, challenges or criticisms to the position advanced by Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca. Since any person who seriously investigates into the nature of dissociation should treat these dialectical materials to fulfill her or his dialectical obligations(i), it is worthwhile to summarize what these scholars say in questioning or denying dissociative schemes of argumentation. In the following I will describe claims directly or indirectly introduced by Rob Grootendorst, M. A. van Rees, and Edward Schiappa. Read more

ISSA Proceedings 2002 – Charles S. Peirce’s Theory Of Abduction And The Aristotelian Enthymeme From Signs

1. What is abduction? A first attempt:

1. What is abduction? A first attempt:

There is hardly a feature in Charles S. Peirce’s thinking, that is more closely associated with his name, and certainly none that he was more proud of himself, than his alleged discovery of a new type or mode of logical reasoning commonly referred to by the name of abduction. In a retrospective note in 1902 in this respect he even declared himself ”an explorer upon untrodden ground.” (CP 2.102)(i). Whether or not this boasting judgment was indeed justified, we shall have to see.

To start with, I shall try to give an outline of what Peirce’s famous theory of abduction really is about. This is not an easy task, for several reasons. First, there is the unfinished, fragmentary and sometimes chaotic state of Peirce’s writings. The great bulk of his huge, monumental oeuvre was never actually published during his lifetime and only survives in manuscripts. So even some of the most important texts relevant to our problem have only been edited very recently or are still awaiting publication. Furthermore, as Peirce kept returning to the problem of abduction and revising it again and again for nearly half a century from the mid 1860s until shortly before his death in 1914, not only are references to abduction scattered all over the many thousands of pages of his oeuvre, but in the course of this long period the whole theory underwent substantial changes and modifications in concept as well as in terminology.

As for terminology, ‘abduction’, the name by which the theory is most commonly known, is in fact only used in a relatively late period by Peirce himself. Instead, in the earliest phase he speaks of ‘inference a posteriori’, then for a long time prefers to call it ‘hypothesis’, until in 1893, in a short advertisement for his Grand Logic, a book which was in fact never printed, he first introduces ‘abduction’ (How to Reason, NEM IV, 353-358). But in 1896 he again proposes a new term ‘retroduction’. In 1901, finally, he firmly establishes ‘abduction’ by differentiating between the hypothesis itself and abduction as the locical process leading to it (Hume on Miracles, CP 6.525). In writings of the years 1904-1906, ‘abduction’ is still occasionally used, but from 1906 onwards Peirce again speaks of retroduction only, without explaining why he totally abandoned ‘abduction’. Some other odd terms like e.g. ‘presumption’ do occur sporadically, too.

As for the concept itself, most scholars who treated the subject, as most prominently K.T. Fann (Fann, 1970), but also A. Burks (Burks, 1946), P.R. Thagard (Thagard, 1977), D.R. Anderson (Anderson, 1986) and R.J. Roth (Roth, 1988), held that there is no unified theory of abduction in Peirce, but rather two different successive concepts with a transitional period in between in the 1890s. This view has recently been challenged by A. Richter in favor of a more continuous progressive change with some of the most essential features, however, remaining unchanged throughout (Richter, 1995, esp. 172-174).

Let us take a closer look. Peirce’s interest for what he later came to call abduction seems to have sprung from three main roots. First, there is an intensive reading of Kant (he started reading the Critique of Pure Reason at the age of 16!), which put into his mind the problem of how to generate synthetic judgments. Second, there is his great interest in the logic of Aristotle and his medieval successors which put him on the track for possible extensions of Aristotelian syllogistic. As a third important source, we may add his considerable expertise in science. He started reading chemistry at Harvard University in 1859. It was certainly in this context that he first came across the problem of how to attain explanatory hypotheses.

A popular description of what Peirce’s theory of abduction amounts to, is that it is a kind of backward inference, or, as Peirce himself once stated, ”rowing up the current of deductive reasoning.” But, one might object, this is not a new idea. For in Aristotle already, there is induction (epagogé) as the reverse form of reasoning in contrast to deductive syllogistic. Peirce, however, maintains that induction cannot be the only alternative to deductive reasoning. Aristotle, on the other hand, was pretty assertive that the dichotomy of deduction and induction was exhaustive. So were the Epicureans, so was Francis Bacon in the 17th century, and so was J.St. Mill in the early 19th, whose title A System of Logic, Ratiocinative and Inductive in this respect is rather telling. Read more

ISSA Proceedings 2002 – On The Relationship Between Argumentation And Narration: A Linguistic Model

In Lo Cascio 1999, I described similarities and differences between narration and argumentation. My standpoint was that both types of systems show similar constructions and that they can often be considered two aspects or faces of the same medal. In this paper I want to highlight some new aspects of the parallelism.

In Lo Cascio 1999, I described similarities and differences between narration and argumentation. My standpoint was that both types of systems show similar constructions and that they can often be considered two aspects or faces of the same medal. In this paper I want to highlight some new aspects of the parallelism.

1. Narration

Narration is characterized by two main categories: Event (E) and Situation (S). The difference between the two categories is an aspectual one, and not a temporal one. Events are states of affairs presented by utterances where the verb is marked by perfective tenses. This means that events are states of affairs presented as closed time intervals. Therefore they have a starting point and an end point.

Situations on the contrary are states of affairs presented as open time intervals, since the verb in the utterance to which they belong is marked by an imperfective tense. The type of the verb, the aktionsart, is also determinant. Stative verbs, for instance,\ represent in general situations. Situations always mark and refer to an event in the same world. They include in other words the time interval of the event in question (cf. Lo Cascio 1982, 1995b, Lo Cascio & Vet 1987, Kamp & Rohrer 1983, Partee 1984). Consider:

1.

It was very warm (S1) and she went out to buy an ice cream (E1). Then she saw John (E2) going to the station (S2). He was carrying a big suitcase (S3)”.

In (1) the situation S1, it was warm, includes and covers the event E1, I She went out: S1ÊE1. Situations, in other words, can indicate properties, or, so called, characteristics, of a world to which an event belongs. In example (1), the situation S1 (a warm day) allows and justifies that in the same world the event E1 (she goes out for an ice cream) takes place. In that same world it would have been possible that also E2 (she saw John) took place independently from S1. S2 in turn characterizes the world where E2 took place. Also S3 characterizes the last mentioned event E2. This gives in theory the possibility to change (1) into (1a) where a new event E3 (she asked whether he was leaving the country for a long time), could for instance be added, cf.:

1a.

It was very warm (S1) and she went out to buy an ice cream (E1). Then she saw John (E2) who was going to the station (S2). He was carrying a big suitcase (S3). She asked whether he was leaving the country for a long time (E3)

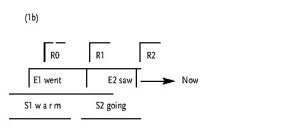

An event, which has been anchored on the temporal axis, delivers, as shown in (1b), a new time interval, the reference time (R), and becomes a given fact, and therefore a situation, in that time interval. In the reference time a new event shall take place. A reference time R, is then a time interval, which is relevant for a new event to take place. R starts after the event, which delivers it has come to the end. The ending point of that event is thus crucial. The temporal interpretation of (1) is:

Where, S1 and S2 are open time intervals. E1 takes place within the time interval R0 and delivers the starting point for R1. E2 takes place within R1 and delivers R2, and so on.

States of affairs can also be presented as in progress (he was going to the station). In that case they are marked by an imperfective morpheme and are considered as situations, i.e. open time intervals. Situations can also be presented through utterances, which are marked by past perfect tense, as the first sentence in (3) shows.

3.

“R had been told the letter would most likely arrive at the Bar Montana on May O May 2, (E/S1) which was the fourth day of his watch, he did not sit in the café across the street but went into the Montana (E1), took a table in the rear (E2) and ordered a sandwich and a beer (E3). The old man was sitting at his usual table near the door (S2).” Brian Moore: The Statement p. 2

In (3) the event R had been told (i.e. a state of affairs represented as closed time interval) is presented as starting point. That event has taken place previously in the same world but it originated a situation, which is of influence at the time interval during which the event E1 takes place. Read more

ISSA Proceedings 2002 – The Conventional Validity Of The Pragma-Dialectical Freedom Rule

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

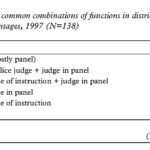

It is as yet unknown what ordinary language users think of discussion moves that are considered fallacious in argumentation theory. Little research has been carried out regarding the standards for reasonableness ordinary arguers apply when evaluating argumentative discourse. Because knowledge of the standards is of both practical and theoretical importance, some years ago we started a comprehensive research project aiming at mapping these standards in a systematic way. The study presented here gives an overview of the results of previous empirical investigations done on the ad hominem fallacy, the ad baculum fallacy, the ad misericordiam fallacy and the fallacy of declaring a standpoint taboo. Although at first sight these fallacious moves may look very different, they nevertheless have one theoretical feature in common: they all involve a violation of the first pragma-dialectical rule, i.e. the freedom rule according to which the parties should not prevent the other party from expressing standpoints or casting doubts. In a critical discussion, all parties have a fundamental and inalienable right to express any standpoint or any doubt they wish to express.

The central question in the empirical studies of which the main trends and results are reported here, was: to what extent do ordinary arguers regard these types of fallacies as reasonable or unreasonable?

2. Conventional validity and violations of the freedom rule.

In the pragma-dialectical argumentation theory, argumentation is seen as a part of a procedure aimed at resolving a difference of opinion concerning the acceptability of a view or a standpoint. The moves made by the protagonist of the standpoint and those made by – or ascribed to – the real or imaginary antagonist in the discourse are regarded reasonable only if they can be considered as a contribution to the resolution of the difference of opinion. In an ideal model of a critical discussion the pragma-dialectical theory describes a discussion procedure that specifies the four stages an argumentative discussion has to go through. There is a ‘confrontation’ stage in which a difference of opinion manifests itself. There is also an ‘opening’ stage, in which the procedural and material points of departure for a critical discussion about the standpoints at issue are established. In the ‘argumentation’ stage the standpoints are challenged and defended. And the critical discussion closes with a ‘concluding’ stage in which the results of the discussion are determined. In order to comply with the dialectical norms of reasonableness, in all four stages the speech acts performed in the discourse have to be in agreement with the rules for critical discussion. If they are not, then they may be considered fallacious.

The different rules for critical discussion derive their ‘problem validity’ from the fact that they are instrumental in resolving the difference of opinion. To resolve a difference of opinion, however, the rules must, besides being effective, also – at least to a certain extent – be acceptable to the parties involved in the difference: they should be intersubjectively approved or ‘conventionally valid’. This criterion is central to the empirical studies done on the (un)reasonableness of the different types of fallacies covered by the pragma-dialectical freedom rule.

According to the rule for the confrontation stage (i.e. the freedom rule) the parties are not allowed to prevent each other from advancing standpoints or casting doubt on standpoints. Attacking the opponent personally by means of an ad hominem fallacy is one way to eliminate him as a serious discussion partner. Traditionally, three variants of the argumentum ad hominem are distinguished, and all these variants were investigated in our first study (Van Eemeren, Grootendorst, Meuffels & Verburg 1997; Van Eemeren, Meuffels & Verburg 2000): (a) an abusive variant, (b) a circumstantial variant, and (c) a you too (tu quoque) variant. In the abusive variant, a head-on personal attack, one party denigrates the other party’s honesty, expertise, intelligence, or good faith, so that the other party loses its credibility. Here is an example taken from the material in our first study (henceforth: ‘ad hominem-study’):

(abusive variant; direct attack)

A: I think a Ford simply drives better; it shoots across the road.

B: How would you know? You don’t know the first thing about cars. Read more