African Urbanism

Speaker: Edgar Pieterse

Chair: Philipp Rode

This event was recorded on 26 January 2011 in U8, Tower One

Africa is the fastest urbanising region in the world, and has become the focus of increasing attention from architects and planners, academics, development agencies and urban think-tanks. Professor Edgar Pieterse argues for a new way of thinking about African cities to accompany this surge of interest and to replace traditional views of African cities as sites of absence and neglect. Rapid urbanisation along with impressive economic growth rates for much of the Continent represents an interesting moment to take stock of how academic discourses capture and animate African urbanism. Edgar Pieterse is holder of the NRF South African Research Chair in Urban Policy. He directs the African Centre for Cities at the University of Cape Town. Philipp Rode is executive director of LSE Cities.

Affordable Housing In South Africa With Prof. Francois Viruly

The housing subsidies announced in the President’s State of the Nation Address and the Finance Minister’s budget speech may well represent arguably the single biggest policy change to date. Joining ABN’s Godfrey Mutizwa in studio to discuss the social impact of affordable housing in South Africa is Prof. Francois Viruly, a property economist and professor at the University of Cape Town.

Estamos bien en el refugio Los 33 – De nasleep van de Chileense mijnramp

In 2010 werd het Chileense Copiapó wereldnieuws. Vlak bij deze stad kwamen op 5 augustus 2010 33 mijnwerkers vast te zitten in de San José mijn. 69 dagen verbleven zij op bijna zevenhonderd meter diepte. Voor het oog van miljoenen tv-kijkers werden zij, op 12 en 13 oktober 2010, één voor één bevrijd. ‘Los 33’ werden als helden onthaald en kregen uitnodigingen om onder meer Disney World in Amerika en voetbalwed-strijden van Real Madrid en Manchester United te bezoeken. Een poos na de ramp gaat het met de ene mijnwerker een stuk beter dan met de ander.

Jimmy Sánchez zit voornamelijk thuis op de bank. Dan staart hij wat voor zich uit en denkt na. Over de tijd die hij doorbracht in de San José mijn. ,,Ik kan alleen maar aan de ramp denken,” zegt de jongste van de 33 mijnwerkers. De nu 21-jarige Chileen heeft het zwaar, is zichzelf kwijt. ,,Vroeger was ik vrolijk en genoot ik van mijn vrienden en familie. Nu voel ik me onbegrepen en wanhopig en ben ik liever alleen. Ik ben nerveus, kan me niet goed concentreren en word soms uit het niets woedend. Ook zijn er dagen dat ik niets anders doe dan huilen. Deze hele situatie maakt me wanhopig en ik weet niet wat te doen.” Read more

Sanitation Challenges In Urban Slums – SCUSA Part 1

Integrated approaches and strategies to address the Sanitation Crisis in Unsewered Slum Areas in African mega-cities

Bwaise III Parish, Kampala, Uganda

Africa, though reported to be the least urbanized continent, is recognized as one where the rate of urbanization is highest. To house all these new city dwellers, informal settlements in the peri-urban areas continue to development and expand.

It is not only housing that the urban population requires: clean drinking water and hygienic sanitary conditions are also essential. Providing water and sanitation in these peri-urban areas is however very difficult, for technical, financial, institutional and spatial reasons.

Lack of proper sanitation not only leads to undignified and unhealthy conditions; stagnant water causes breeding pools for malaria, plus the streams entering and leaving the slum catchment, either as surface water or groundwater, form a significant pollutant load.

This water is polluting drinking water and, due to extremely high phosphorus fluxes from the slum catchments, eutrophying surface water. Therefore, the main research question of this project is: How to improve sanitation in urban slums, with emphasis on reducing the output of nutrients leaving the slum?

Scusa

Objectives: to identify and implement low cost integrated sustainable sanitation solutions to provide excreta and greywater management in a typical slum area. To determine the financial, institutional, and sociological mechanisms or boundary conditions for successful implementation of sustainable sanitation solutions in this urban slum and to use the lessons learned in other slum areas. To determine the effect of slums and of environmentally sustainable sanitation in slums on groundwater and surface water quantity and quality. In answering to these research objectives, UNESCO-IHE is joining forces with Makarere University from Kampala Uganda.

Citizen Journalists Give a New Face to Nairobi’s Slums

thinkafricapress.com – Nairobi, Kenya. December, 6, 2012. Through journalism, residents of Nairobi’s slums are taking it upon themselves to highlight injustices and create a balanced image of slum life.

Newspaper editor Vincent Achuka was behind schedule. The November issue of his Ghetto Mirror newspaper had arrived a week late from the printer, and he had an hour to finalise story assignments for the next. Then, he and his reporters had to distribute hundreds of papers by hand across Kibera, Nairobi’s largest slum. It was a typical Saturday morning in the life of a slum journalist.

Read more: http://thinkafricapress.com

Terra Firma: Ashore in the Bay of Strangers

Friday, 25 August 1995 – “Bosun – topside!” The Captain’s command over the intercom aroused me from a deep sleep. Henri, jumping from his cot, rushed out to film the action on deck. Soon the muffled rattling of the anchor chain reverberated throughout the ship: we were dropping anchor. Slowly, I got up. Fleetingly, ever so fleetingly, a wave of revulsion suffused my body, and I tried not to think about what was outside: a fog-shrouded, ice-cold sea and a huge, empty island. I glanced at my watch: 7:15 a.m. Through the porthole I could see a calm sea, light blue under a low, grey sky. If this was Ivanov Bay, the grave search party would go ashore. If it wasn’t, only the Captain might know where on earth we may be. I got dressed and hurried outside. In the light, drizzly mist that engulfed the ship, Jerzy and Bas were siphoning gasoline into lemonade bottles from a big, rusty fuel barrel on the foredeck, using a rubber hose. Inside, the breakfast table had been set, but there was no time to eat. The landing of the grave-searchers was busily being prepared, as Boyarsky was threatening that the sea might soon get rough again. Only George, with aristocratic unconcern, sat sipping a cup of tea in the otherwise empty mess room. The corridors teemed with foot traffic. The hum of electric motors resonated through the steel vessel as the deck crane deposited a huge stack of wooden beams and planks from the hold into the landing craft. For protection against bears, the Ivanov Bay group would be constructing a hut for their stay. On deck, the atmosphere was frenzied and tension was palpable, with good-byes adding to the din of cargo handling.

Friday, 25 August 1995 – “Bosun – topside!” The Captain’s command over the intercom aroused me from a deep sleep. Henri, jumping from his cot, rushed out to film the action on deck. Soon the muffled rattling of the anchor chain reverberated throughout the ship: we were dropping anchor. Slowly, I got up. Fleetingly, ever so fleetingly, a wave of revulsion suffused my body, and I tried not to think about what was outside: a fog-shrouded, ice-cold sea and a huge, empty island. I glanced at my watch: 7:15 a.m. Through the porthole I could see a calm sea, light blue under a low, grey sky. If this was Ivanov Bay, the grave search party would go ashore. If it wasn’t, only the Captain might know where on earth we may be. I got dressed and hurried outside. In the light, drizzly mist that engulfed the ship, Jerzy and Bas were siphoning gasoline into lemonade bottles from a big, rusty fuel barrel on the foredeck, using a rubber hose. Inside, the breakfast table had been set, but there was no time to eat. The landing of the grave-searchers was busily being prepared, as Boyarsky was threatening that the sea might soon get rough again. Only George, with aristocratic unconcern, sat sipping a cup of tea in the otherwise empty mess room. The corridors teemed with foot traffic. The hum of electric motors resonated through the steel vessel as the deck crane deposited a huge stack of wooden beams and planks from the hold into the landing craft. For protection against bears, the Ivanov Bay group would be constructing a hut for their stay. On deck, the atmosphere was frenzied and tension was palpable, with good-byes adding to the din of cargo handling.

Freed from all its cables, our landing craft, a red steel barge five meters long, danced merrily atop the waves. Once the entire Ivanov gang had climbed down the rope ladders, the droning plashkot sailed rapidly into the haze. Bundled up in gear as if ready to go ashore myself, I stood in a light rain atop Kiriev’s bridge and followed the progress of the landing through binoculars. A trio of long, rustbrown walruses glided by the red craft through the pale blue sea. It was easy to distinguish their bristling snouts, which spit out a spray of condensation and water when the animals are surfacing. It was +4°C. Novaya Zemlya was just a dark strip of land, the elevations above ca. 100 m disappearing into the low clouds. There was little snow.

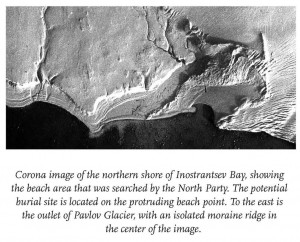

By 11:15 a.m., the Ivanov group was ashore. The landing craft delivered a second load and was hoisted aboard. Kiriev raised anchor, but would not sail towards Ice Harbor. It had been decided to seek shelter from a new storm in Inostrantsev Bay, on the west coast of the island. Excitement swept over the ship when, at noon, we saw the first unobtrusive iceberg float by: the entire oyage so far had not provided this many sights. The silent flotilla of blue sculptures grew by the hour, indicating the proximity of calving glaciers. Our arrival in Inostrantsev Bay was estimated for 3:00 p.m. The plan calls for a reconnaissance sortie with two groups along the beaches of the bay, to search for cairns. Boyarsky requests that we be specifically alert for objects indicating the presence of the ancient Pomors and the Nazis, who operated in greatest secrecy on these shores during their Arctic campaigns. The approaching landing put us back on the alert. Bas distributed ammunition for the rifles and reviewed the arms discipline. “Should a polar bear come after us and we decide to fire at him,” he instructed us, “we’ll follow our firing-range routine. The shooter kneels down and someone else counts the bear’s approach: fifty meters… forty meters… thirty meters… Don’t stare at the bear, but focus on his chest or on his shoulder. There will be three cartridges in the magazine. For reasons of safety, do not keep a cartridge in the chamber. Remember, the second man keeps additional ammo at the ready.”

Self-sufficiency is imperative for one venturing out in the Arctic, and it was high time to get my gear in order. (“Coming along?” Anton, our film director, would tell the viewer. Small kids start crying, young women turn off the TV.) What do I need? After polar bears, the unpredictable weather, which can change from quiet to severe in half an hour, is the greatest challenge. The land is barren and provides no shelter. There is no snow in which the stranded traveler could dig a shelter against the piercing winds. To be lightly equipped and able to move about swiftly, I packed the thin, reinforced Gore-Tex cover of the Navy-issue sleeping bag and a small stove, with a one-liter bottle of gasoline, enough for two weeks. High-grade gasoline is harder to come by in these parts of the world than diesel or kerosene but more practical because kerosene fuel oil has a flash point well above 40°C and won’t ignite easily in low-temperature environs. I took my down jacket, wrapped in a plastic bag, so I could leave my sleeping bag on board. I took wax for my boots, packages of instant soup, chocolate milk, and mashed potatoes. There would be sufficient meltwater on land, but just to be sure, I filled my canteen. On a waist belt, I carried the dagger and a pouch containing flare gun, GPS, a set of waterproof-packed batteries, a notebook with waterproof paper, and a pencil. I took some extra film and decided where to put everything: the rain gear fortunately has plenty of zippered pockets to stow away the many little items I need to keep track of.

The sea was calm: smooth as glass. The landing craft glided over in fifteen minutes and at 4:00 p.m. ground onto the steep, gravel beachfront. The sailors kept the engine running to maintain a solid lock while we disembarked. In clouds of smoke and steam, we climbed the steep ridge of loose gravel. Then, after reversing the propeller’s motion, the plashkot quickly retreated into the fog.

- Page 2 of 3

- previous page

- 1

- 2

- 3

- next page