Imperialism Is Alive And Kicking: A Marxist Analysis Of Neoliberal Capitalism

The concept of imperialism has fallen out of the political lexicon of many leftists in the West, with some deeming the concept irrelevant for understanding the dynamics of contemporary capitalism.

Marxist economist Prabhat Patnaik has been one of the leading voices countering this trend. In A Theory of Imperialism, a book he co-authored with Utsa Patnaik, Patnaik explores how a new form of imperialism is at work in the unfolding of the capitalist system.

In this exclusive interview for Truthout, Patnaik states the case for the continuing relevance of imperialism as an analytical construct for understanding and challenging effectively the logic and dynamics of contemporary capitalism.

C.J. Polychroniou: How do you define imperialism and what imperialist tendencies do you detect as inherent in the brutal expansion of the logic of capitalism in the neoliberal global era?

Prabhat Patnaik: The capitalist sector of the world, which began by being located, and continues largely to be located, in the temperate region, requires as its raw materials and means of consumption a whole range of primary commodities which are not available or producible, either at all or in adequate quantities, within its own borders. These commodities have to be obtained from the tropical and sub-tropical region within which almost the whole of the Third World is located; and the bulk of them (leaving aside minerals) are produced by a set of petty producers (peasants). What is more, they are subject to “increasing supply price,” in the sense that as demand for them increases in the capitalist sector, larger quantities of them can be obtained, if at all, only at higher prices, thanks to the fixed size of the tropical land mass.

This means an ex ante tendency toward accelerating inflation as capital accumulation proceeds, undermining the value of money under capitalism and hence the viability of the system as a whole. To prevent this, the system requires that with an increase in demand from the capitalist sector, as capital accumulation proceeds, there must be a compression of demand elsewhere for these commodities, so that the net demand does not increase, and increasing supply price does not get a chance to manifest itself at all.

Such demand-compression occurs above all through the imposition of an income deflation on the petty producers, and on the working population in general, in the Third World. This was done in the colonial period through two means: one, “deindustrialization” or the displacement of local craft production by imports of manufactures from the capitalist sector; and two, the “drain of surplus” where a part of the taxes extracted from petty producers was simply taken away in the form of exported goods without any quid pro quo. The income of the working population of the Third World, and hence its demand, was thus kept down; and metropolitan capitalism’s demand for such commodities was met without any inflationary threat to the value of money. Exactly a similar process of income deflation is imposed now upon the working population of the Third World by the neoliberal policies of globalization.

I mean by the term “imperialism” the arrangement that the capitalist system sets up for imposing income deflation on the working population of the Third World for countering the threat of inflation that would otherwise erode the value of money in the metropolis and make the system unviable. “Imperialism” in this sense characterizes both the colonial and the contemporary periods.

Henk A. Becker ~ Generaties van geluksvogels en pechvogels

Paperback

16,5 x 24 cm

258 pag.

ISBN 978 90 361 0275 9

Derde, gewijzigde druk 2017

Euro 27,50

E-book: ISBN 987 90 361 0276 6

Euro 15,00

Grote maatschappelijke gebeurtenissen smeden losse aantallen tijdgenoten tot generaties samen. Elke generatie heeft met bedreigingen en kansen te maken. Elke generatie herbergt geluksvogels en pechvogels. Bij sommige generaties gaat het om relatief veel geluksvogels, bij andere om relatief veel pechvogels. De geluksvogels proberen hun gunstige positie te behouden en zo mogelijk te versterken. De pechvogels doen hun best om hun lot te verbeteren. In onze tijd moeten de jongere generaties assertief hun kans op gunstig opgroeien en een stevige economische positie verdedigen. De oudere generaties vormen met hun zilvergrijs menselijk kapitaal een goudmijn, die wij in de komende decennia hard nodig zullen hebben om de te verwachten reeks explosies van de demografische tijdbom op niveau te overleven.

Aanvullingen op het boek verschijnen op: http://rozenbergquarterly.com/category/europe_generations/

Het boek is afgestemd op een brede lezerskring. In enkele duidelijk aangegeven tekstfragmenten staan verwijzingen naar de vakliteratuur.

Henk A. Becker (1933) is emeritus hoogleraar sociologie aan de Universiteit Utrecht. Zijn specialisaties vormen een ‘tripod’. Bij de inhoudelijke poot gaat het om cohorten en generaties. De methodische poot bevat methoden voor generatieonderzoek en strategieën voor generatiebewust beleid. De derde poot heeft betrekking op enkele meta-aspecten van zijn discipline, namelijk de ‘state of the art’ in de sociologie. Het Tripod model kan wetenschappers ervoor behoeden om een vakidioot te worden.

Henk A. Becker ~ Generations of Lucky Devils and Unlucky Dogs

Paperback

Paperback

16,5 x 24 cm

258 pag.

ISBN 978 90 361 0 277 3

2012

E-book ~ ISBN 987 90 361 0275 9

Silver-grey manpower is a gold mine to society. One by one, the baby boom cohorts will reach the age of 65 starting from 2010. They are large cohorts, relatively well educated and healthy with considerable pension and health care rights. In short, they are lucky devils. As a result of ageing, cohorts that were born in 1985 onwards and that enter the labour market as from approximately 2010 will be required to pay many additional taxes during the course of their entire working life spanning more than forty years. They are, in short, unlucky dogs. Redistribution of joys and burdens could trigger conflicts between generations. A better solution is to identify and deploy society’s hidden resources.

Taking this issue as a basis, the book in hand explores strategies that enable senior citizens and young people to give meaning to solidarity among generations, for a start in 2012 as the European Year for Active Ageing, but also as part of Europe 2020, the European Commission’s 2010-2020 strategy.

With these two strategies journalists and television producers will swing into action. In secondary and higher education as well as in universities more papers on life courses and patterns of generations will be written than ever before. Senior citizens’ unions but actually all social organizations will organize lectures. Educated laymen will wish to go deeply into this issue.

Henk A. Becker (1933) is Professor Emeritus of Sociology at Utrecht University in the Netherlands. He has worked on a research project focusing on generations since 1985.

Michael Dagan ~ Online Privacy Guide For Journalists 2017

Many veteran journalists, but not only these, surely noticed that we are all of a sudden bombarded again from all-over with mentions of Watergate. Books like George Orwell’s 1984 are on display at bookstores and an air of danger to freedom of speech and freedom of the press is spreading slowly like a dark cloud over the Western Hemisphere, raising old fears.

Many veteran journalists, but not only these, surely noticed that we are all of a sudden bombarded again from all-over with mentions of Watergate. Books like George Orwell’s 1984 are on display at bookstores and an air of danger to freedom of speech and freedom of the press is spreading slowly like a dark cloud over the Western Hemisphere, raising old fears.

When an American serving president accuses a former president of surveillance; when he prevents central US media outlets access – so far always granted, and taken for granted – to press conferences he holds; and when he incessantly knocks and accuses the media of being the country’s enemy number one, it isn’t surprising that memories of President Nixon surface up more with every self-pitying tweet about SNL, and that even Republican Senators such as John McCain express fear for the future of democracy.

And McCain is not alone. Many journalists whom I have spoken with recently, expressed concern for whatever lays ahead for the freedom of the press. At a time when it’s possible to express the following statement – “Donald Trump controls the NSA” – and not be held a liar, anything’s possible. Add that to the fact that recent news on CIA taught us that almost all encryption systems can be compromised, if someone has the perseverance to crack them – and you are en route to envisioning an utterly Dystopian world, where you cannot even get too comfortable laying on your sofa, in front of your own smart TV.

The good news is that it is nevertheless possible to make it difficult for anyone to try and intercept your emails, the text messages you’re sending or your phone calls. You can take measures to make the lives of those who want to uncover your sources and the information being revealed to you, much harder. Of course, the degree of effort you’re prepared to take to protect your privacy, your sources’ anonymity and your data’s safety, should be commensurate to the likelihood of a real threat, be that hacking or spying.

Read more: https://www.vpnmentor.com/blog/online-privacy-journalists/

See also: https://www.cloudwards.net/online-privacy-guide/

Het begrip ‘joods-christelijk’ en taboe herinneringen

Midden in de huiskamer van mijn ouders stond een grote boekenkast. Vroeger zat ik daar op de grond fotoalbums te bekijken. Of de kinderbijbels en sprookjesboeken. Die stonden op ooghoogte.

Midden in de huiskamer van mijn ouders stond een grote boekenkast. Vroeger zat ik daar op de grond fotoalbums te bekijken. Of de kinderbijbels en sprookjesboeken. Die stonden op ooghoogte.

De rest van de boeken zag ik later pas. De bruine banden van Lou de Jong en vooral veel boeken van joodse schrijvers over de tweede wereldoorlog: Abel Herzberg, Primo Levi, Emmanuel Levinas en Elie Wiesel. Ieder jaar haalde mijn vader de kast zorgvuldig leeg, plank voor plank, boek voor boek, maakte alles schoon en zette de boeken op precies dezelfde plek terug. Al snel wist ik: dit was geen gewone kast, zoals de servieskast dat was, maar een bijzonere plek: een plek van herinnering.

Het begrip ‘joods-christelijk’ zou je ook zo kunnen zien. Als een manier om te herinneren. Een soort bril die je opzet om naar de geschiedenis te kijken. Dat kan een absurdistische bril zijn: bijvoorbeeld bij Sybrand Buma in een verkiezingsdebat. Daar claimde hij dat seksegelijkheid een typisch ‘joods-

christelijke’ waarde is die duizenden jaren teruggaat. Alsof de geschiedenis van het christendom een eeuwenlange geschiedenis was van vrouwenemancipatie. Ik zeg hier nadrukkelijk ‘christendom’, want met Joods-zijn en jodendom heeft de uitspraak van Buma weinig te maken: hij gebruikt ‘joods-christelijk’ en christelijke gewoon door elkaar. Zijn beroep op een ‘joods-christelijke beschaving’ lijkt er vooral op gericht een contrast te creëren met de niet-‘joods-christelijken’: moslims.

Die boekenkast van m’n ouders was een poging om serieuzer over de relatie tussen joods en christelijk na te denken. Door te herinneren dat joden in het christelijke Europa hooguit als voorwaardelijke burgers zijn geaccepteerd. Dat christelijke en later seculiere denkers het jodendom en joden nauwelijks als onderdeel van ‘hun’ beschaving hebben gezien. In het beste geval is het begrip ‘joods-christelijk’ dus het herinneren dat ‘joods-christelijk’ in Europa nooit zo harmonieus heeft bestaan. Bij auteurs als Levi en Levinas is daar geen ontkomen aan: ze schrijven terug en claimen hun visie op de Europese of nationale cultuur. Die boeken waren voor m’n vader geen goedkope verwijzing naar een ideale beschaving, zoals bij Buma, maar een herinnering dat wij onderdeel uitmaken van een geschiedenis die verre van ideaal is.

Tegelijk blijft de vraag: wat werd er niet herinnerd in die kast? Waarom stonden er wel boeken van de Italiaans Primo Levi, maar niet van de Tunesische Albert Memmi of de Arabisch Joodse Ella Shohat? Allebei ook joodse schrijvers die kritisch reflecteren op de rol van Europa: niet vanuit Europa, maar vanuit de (voormalige) koloniën waar hun wortels liggen.

Read more

Global Population Ageing, The Sixth Kondratieff Wave, And The Global Financial System

Abstract

Abstract

Concerns about population ageing apply to both developed and many developing countries and it has turned into a global issue. In the forthcoming decades the population ageing is likely to become one of the most important processes determining the future society characteristics and the direction of technological development. The present paper analyzes some aspects of the population ageing and its important consequences for particular societies and the whole world. Basing on this analysis, we can draw a conclusion that the future technological breakthrough is likely to take place in the 2030s (which we define as the final phase of the Cybernetic Revolution). In the 2020s – 2030s we will expect the upswing of the forthcoming sixth Kondratieff wave, which will introduce the sixth technological paradigm (system). All those revolutionary technological changes will be connected, first of all, with breakthroughs in medicine and related technologies. We also present our ideas about the financial instruments that can help to solve the problem of pension provision for an increasing elderly population in the developed countries. We think that a more purposeful use of pension funds’ assets together with an allocation (with necessary guarantees) of the latter into education and upgrading skills of young people in developing countries, perhaps, can partially solve the indicated problem in the developed states.

Keywords: the sixth Kondratieff wave, the sixth technological paradigm, Cybernetic Revolution, population ageing, world finance, pension funds, human capital, developed countries, developing countries.

Human capital is one of the most important drivers of economic development whose contribution to the growth of production and innovations is constantly

increasing. According to the OECD definition, human capital is ‘the knowledge, skills, competencies and attributes embodied in individuals that facilitate the creation of personal, social and economic well-being’ (OECD 2001: 18; see also Kapelyushnikov 2012: 6–7). Human capital is central to debates about welfare, education, health care, and retirement. However, we think that the latter (i.e., retirement) is less frequently debated than it should be. Meanwhile, in the West the rapid population ageing actually devaluates the national human capital in every developed country. There are certain grounds to expect that if the ageing generation is not substituted by a more numerous generation of young specialists, the share of the elderly population will increase and the human capital is likely to decline.

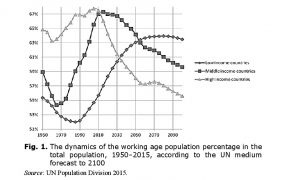

Thus, while the human capital as well as its contribution to the economic development is significantly larger in the developed countries than in the developing ones, the situation with demographic structure of human capital is different. The developing countries’ situation is significantly better at this point, and this can increasingly contribute to the economic competition between the First and Third worlds. We should also take into consideration the fact that the generation of highly educated pensioners in the developed states has increased the demands on society and they play a more active political role than the generation of uneducated ‘old men’ in the developing countries. While the West has apparently depleted its demographic dividend, many developing countries, in fact, are only in the process of its accumulation. And consequently, in this context they can get the most important advantage in the coming decades (see Fig. 1).

Thus, while the human capital as well as its contribution to the economic development is significantly larger in the developed countries than in the developing ones, the situation with demographic structure of human capital is different. The developing countries’ situation is significantly better at this point, and this can increasingly contribute to the economic competition between the First and Third worlds. We should also take into consideration the fact that the generation of highly educated pensioners in the developed states has increased the demands on society and they play a more active political role than the generation of uneducated ‘old men’ in the developing countries. While the West has apparently depleted its demographic dividend, many developing countries, in fact, are only in the process of its accumulation. And consequently, in this context they can get the most important advantage in the coming decades (see Fig. 1).

This also confirms the idea of growing convergence between the developed and developing countries that we adhere to, as the current differences in the

demographic structure and potentialities of the demographic dividend will contribute to the fact that at least in the next two decades the developing countries’ growth rates will be on average higher than those of the developed countries, although this process can proceed with certain interruptions (see Grinin 2013а, 2013b, 2013c, 2014, 2015; Korotayev and Khaltourina 2009; Khaltourina and Korotayev 2010; Korotayev, Khaltourina, Malkov et al. 2010; Korotayev and Bozhevol’nov 2010; Korotayev, Malkov et al. 2010; Malkov, Korotayev and Bozhevol’nov 2010; Malkov et al. 2010; Korotayev, Zinkina et al. 2011a; 2011b, 2012; Korotayev and de Munck 2013, 2014; Zinkina et al. 2014; Korotayev and Zinkina 2014; Korotayev, Goldstone, and Zinkina 2015; Grinin and Korotayev 2014a, 2014b, 2015а).

Read more