Sjibbolet: de bijbel in onze literatuur

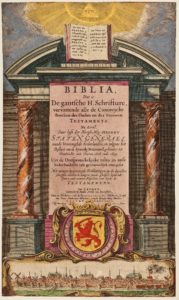

De bijbel is, overeenkomstig zijn inhoud, alomtegenwoordig in onze letteren: citaten uit of allusies aan de Schrift komen in ontelbare gedichten, verhalen en romans voor. Maar om zijn invloed waar te nemen, is niet meteen een tijdrovende tekstanalyse nodig, menige boektitel is al een woordelijk citaat of variant daarop.

De bijbel is, overeenkomstig zijn inhoud, alomtegenwoordig in onze letteren: citaten uit of allusies aan de Schrift komen in ontelbare gedichten, verhalen en romans voor. Maar om zijn invloed waar te nemen, is niet meteen een tijdrovende tekstanalyse nodig, menige boektitel is al een woordelijk citaat of variant daarop.

Hedda Martens (1947) debuteerde in 1982 met de bundel Sjibbolet en andere verhalen. Een sjibbolet of schibbolet is een kenmerk waaraan herkend kan worden of iemand tot een bepaalde groep of overtuiging behoort. Het bijbelboek Richteren 12:5-6 geeft daarvoor de oorspronkelijke verklaring.

Tijdens een oorlog tussen de Gileadieten en Efraïmieten poogden de laatsten, door zich als Gileadieten te vermommen, de Jordaan over te vluchten.

“Wanneer nu een der vluchtelingen van Efraim zeide: Laat mij oversteken, dan zeiden de mannen van Gilead tot hem: Zijt gij een Efraïmiet? En antwoordde hij: Neen, dan zeiden zij tot hem: Zeg eens sjibboleth. Zeide hij dan: sibboleth, en kon hij het dus niet op de juiste wijze uitspreken, dan grepen zij hem en sloegen hem dood.”

Maarten ‘t Harts roman De Jacobsladder (1986) verwijst naar een droom die aartsvader Jakob had:

“Toen droomde hij, en zie, op de aarde was een ladder opgericht, waarvan de top tot aan de hemel reikte, en zie, engelen Gods klommen daarlangs op en daalden daarlangs neder.” (Genesis 28:12)

Ook Marnix Gijsen (1899-1984) putte voor een titel uit de bijbel. De vleespotten van Egypte (1952) is gebaseerd op de uitdrukking `hunkeren naar de vleespotten van Egypte’, die voortkomt uit het gemopper van de Israëlieten tegen Mozes en Aaron, die hen uit Egyptische slavernij bevrijd hadden en naar het beloofde land voerden. Exodus 16:3:

“Och, dat wij door de hand des Heren in het land Egypte gestorven waren, toen wij bij de vleespotten zaten en volop brood aten; want gij hebt ons in deze woestijn geleid om deze gehele gemeente van honger te doen omkomen.”

Theo Kars (1940-2015) verzamelde een aantal beschouwingen over literatuur onder de van zelfoverschatting getuigende titel Parels voor de zwijnen (1975). Dat baseerde hij, zij het wellicht niet uit eigen waarneming, op Mattheus 7:6, waarin Jezus oproept:

“Geeft het heilige niet aan de honden en werpt uw paarlen niet voor de zwijnen, opdat zij die niet vertrappen met hun poten en, zich omkerende, u verscheuren.”

Ik kan die uitdrukking nooit lezen zonder onmiddellijk te denken aan een anekdote over de Amerikaanse schrijfster Dorothy Parker, die eens gelijktijdig met een aanzienlijk jongere collega een deur naderde waar maar één van hen tegelijk door kon. De jongste hield haar pas in, zeggend ‘Age before beauty’. Parker nam meteen de uitnodiging aan, onder de woorden ‘Pearls before swine’.

Ook Nescio’s bundel Mene Tekel (1946) heet naar een spreuk uit het Oude Testament. Daniël 5:25-28 verhaalt hoe tijdens een feest van Belsazar, koning der Chaldeeën, lichtende letters op de muur verschijnen:

“Dit is het schrift, dat geschreven is: Mene, mene, tekel ufarsin. Dit is de uitlegging van de woorden: Mene: God heeft uw koningschap geteld en er een einde aan gemaakt; Tekel, gij zijt in de weegschaal gewogen en te licht bevonden; Peres: uw koninkrijk is gebroken en aan de Meden en Perzen gegeven.”

Uiteraard heeft dit fragment ook de uitdrukking ‘gewogen maar te licht bevonden’ opgeleverd, alsook ‘een teken aan de wand’. Daniël 5:5 beschrijft hoe Belsazar de tekenen ziet verschijnen:

“Terzelfdertijd verschenen vingers van een mensenhand, die tegenover de luchter op de kalk van de wand van het koninklijk paleis schreven, en de koning zag de rug van de hand, die aan het schrijven was.”

Mene tekel vond ook zijn weg naar Nederlandse poëzie, bijvoorbeeld naar deze regels uit het gedicht ‘Glazenwasser’ (1949) van Gerrit Achterberg

Handen- en voetental

verrichten in de lucht

een klein gebarenspel, een klucht

die hij alleen begrijpen zal;

het mene tekel en getal

van roekeloze hemelzucht.

Marnix Gijsens De barmhartige Samaritaan (1952) gaat terug op het evangelie van Lucas, op de gelijkenis van de Samaritaan die zich, in tegenstelling tot een priester, het lot aantrok van een door overvallers gewonde reiziger:

“Doch een Samaritaan, die op reis was, kwam in zijn nabijheid, en toen hij hem zag, werd hij met ontferming bewogen. En hij ging naar hem toe, verbond zijn wonden, goot er olie en wijn op; en hij zette hem op zijn eigen rijdier, bracht hem naar een herberg en verzorgde hem.” (Luc. 10:33-34)

The World Today With Tariq Ali – Jewish Arabs And Cultural Cleansing

This week Tariq speaks to New York University scholar Ella Shohat about the history of Jewish people in the Middle East and North Africa, using her Baghdadi heritage as a starting point. Ella tackles the dominant, Western narrative on Jewishness, asserting that Jewish history, culture and opinion aren’t monolithic. Arab Jews, in particular, face the dichotomy of being considered both of the East and of the West – or, as Edward Said described it, being both Oriental and Orientalist.

Music in this video

Listen ad-free with YouTube Premium

Song – Shostakovich : String Quartet No.9 in E flat major Op.117 : III Allegretto

Artist – Brodsky Quartet

Album – Shostakovich : String Quartet No.9 in E flat major Op.117 : III Allegretto

Licensed to YouTube by WMG (on behalf of Teldec Classics International), and 5 Music Rights Societies

Song – Desert Life

Artist – Terry Devine-King

Album – ANW1181 – Editor’s Series – Middle East 3

Licensed to YouTube by Audio Network (on behalf of Audio Network plc); Audio Network (music publishing), and 6 Music Rights Societies

Jewish Art: Not In Heaven – Artists As Partners In Creation

Curators Judith Cardozo and Dr. Susan Nashman Fraiman present The exhibition “Not in Heaven”, which was part of the Jerusalem Biennale 2019. The exhibit was a response of designers and artists to a dramatic story from the Talmud.

The presentation includes individual items from the exhibition itself, as well as musings on the role of Jewish texts as sources of inspiration for artists.

More info: https://jewishartsalon.org/2020/04/21/not-in-heaven-artists-as-partners-in-creation/

Dr. Susan Nashman Fraiman is a lecturer, researcher and curator of Jewish and Israeli art. She has taught at Hebrew College in Newton, Ma, the Pardes Institute of Jewish Studies and currently teaches at the Rothberg School for Overseas Students. She served for five years as the collection manager at the Yad Vashem Art Museum and curated the exhibit “The Fine Line” in the 2015 Jerusalem Biennale.

Website: www.artinisrael.net

Born in New York City, Judy Cardozo, Independent Curator and writer, educated at Pratt Institute and Barnard College, worked at the National Foundation for Jewish Culture and curated exhibitions at the Bronx Museum, Yeshiva University Museum and the Bertha Urdang Gallery. In Toronto, she was curator of the Beth Tzedec Museum and and co-produced the ASHKENAZ Festival at Harbourfront. In Israel since 2000, she worked at the Center for Jewish Art and has been involved with the Jerusalem Biennale.

Organized and hosted by the Jewish Art Salon; co-sponsored by Art Kibbutz and Jada Art.

Edited by Jonah Rubin-Flett. Assistance by Bluma Gross.

The Political Economy Of Saving The Planet. An Interview With Noam Chomsky & Robert Pollin

What needs to be done to advance a successful political mobilization on behalf of a global Green New Deal—a program that includes emissions reductions, expands renewable energy sources, addresses the needs of vulnerable workers, and promotes sustainable and egalitarian economic growth? Political scientist C. J. Polychroniou spoke with Noam Chomsky and economist Robert Pollin, who has been at the forefront of the fight for an egalitarian green economy for more than a decade, to discuss prospects for change, the connections between climate and the COVID-19 pandemic, and whether eco-socialism is a viable option for mobilizing people in the struggle to create a green future.

This conversation was adapted from Chomsky and Pollin’s new book Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet.

C. J. Polychroniou: How does the coronavirus pandemic, and the response to it, shed light on how we should think about climate change and the prospects for a global Green New Deal?

Noam Chomsky: At the time of writing, concern for the COVID-19 crisis is virtually all-consuming. That’s understandable. It is severe and is severely disrupting lives. But it will pass, though at horrendous cost, and there will be recovery. There will not be recovery from the melting of the arctic ice sheets and the other consequences of global warming.

Not everyone is ignoring the advancing existential crisis. The sociopaths dedicated to accelerating the disaster continue to pursue their efforts, relentlessly. As before, Trump and his courtiers take pride in leading the race to destruction. As the United States was becoming the epicenter of the pandemic, thanks in no small measure to their folly, the White House cabal released its budget proposals. As expected, the proposals call for even deeper cuts in healthcare support and environmental protection, instead favoring the bloated military and the building of Trump’s Great Wall. And to add an extra touch of sadism, the budget promotes a fossil fuel ‘energy boom’ in the United States, including an increase in the production of natural gas and crude oil.”

Meanwhile, to drive another nail in the coffin that Trump and associates are preparing for the nation and the world, their corporate-run EPA weakened auto emission standards, thus enhancing environmental destruction and killing more people from pollution. As expected, fossil fuel companies are lining up in the forefront of the appeals of the corporate sector to the nanny state, pleading once again for the generous public to rescue them from the consequences of their misdeeds.

In brief, the criminal classes are relentless in their pursuit of power and profit, whatever the human consequences. And those consequences will be disastrous if their efforts are not countered, indeed overwhelmed, by those concerned for “the survival of humanity.” It is no time to mince words out of misplaced politeness. “The survival of humanity” is at risk on our present course, to quote a leaked internal memo from JPMorgan Chase, America’s largest bank, referring specifically to the bank’s genocidal policy of funding fossil fuel production.

One heartening feature of the present crisis is the rise in community organizations starting mutual aid efforts. These could become centers for confronting the challenges that are already eroding the foundations of the social order. The courage of doctors and nurses, laboring under miserable conditions imposed by decades of socioeconomic lunacy, is a tribute to the resources of the human spirit. There are ways forward. The opportunities cannot be allowed to lapse.

Robert Pollin: In addition to the fundamental considerations that Noam has emphasized, there are several other ways in which the climate crisis and the coronavirus pandemic intersect. One underlying cause of the COVID-19 outbreak—as well as other recent epidemics such as Ebola, West Nile, and HIV—has been the destruction of animal habitats through deforestation and human encroachment, as well as the disruption of the remaining habitat through the increasing frequency and severity of heat waves, droughts, and floods. As the science journalist Sonia Shah wrote in February 2020, habitat destruction increases the likelihood that wild species “will come into repeated intimate contact with the human settlements expanding into their newly fragmented habitats. It’s this kind of repeated, intimate contact that allows the microbes that live in their bodies to cross over into ours, transforming benign animal microbes into deadly human pathogens.”

It is also likely that people who are exposed to dangerous levels of air pollution will face more severe health consequences than those breathing cleaner air. Aaron Bernstein of Harvard’s Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment states that “air pollution is strongly associated with people’s risk of getting pneumonia and other respiratory infections and with getting sicker when they do get pneumonia. A study done on SARS, a virus closely related to COVID-19, found that people who breathed dirtier air were about twice as likely to die from the infection.”

A separate point that was raised over the worst months of the COVID-19 pandemic was that the responses in the countries that immediately handled the crisis more effectively, such as South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore, demonstrated that governments are capable of taking decisive and effective action in the face of crisis. The death tolls from COVID-19 in these countries were negligible, and normal life returned relatively soon after governments imposed initial lockdowns. Similarly decisive interventions could successfully deal with the climate crisis where the political will is strong and the public sectors are competent.

There are important elements of truth in such views, but we should also be careful to not push this point too far. Some commentators have argued that one silver lining outcome of the pandemic was that, because of the economic lockdown, fossil fuel consumption and CO2 emissions plunged alongside overall economic activity during the recession. While this is true, I do not see any positive lessons here with respect to advancing a viable emissions program that can get us to net zero emissions by 2050. Rather, the experience demonstrates why a degrowth approach to emissions reduction is unworkable. Emissions did indeed fall sharply because of the pandemic and the recession. But that is only because incomes collapsed and unemployment spiked over this same period. This only reinforces the conclusion that the only effective climate stabilization path is the Green New Deal, as it is the only one that does not require a drastic contraction (or “degrowth”) of jobs and incomes to drive down emissions.

Climate Change Intensifies Inequality: An Interview With Gregor Semieniuk

This is part of PERI’s economist interview series, hosted by C.J. Polychroniou.

C.J. Polychroniou: You studied International Relations in Germany, at the Technische Universität Dresden, but ended up pursuing graduate studies in economics in the USA. What drew you into the “dismal science?”

Gregor Semieniuk: In Dresden, the program’s content spanned economics, public law and political science. What intrigued me about economics was that on the one hand it seemed necessary to grapple with the most intractable global issues of the time: for instance, why it was so difficult to increase most countries’ material affluence, how renewable energy could quickly replace the existing energy supply, and of course how the 2007-08 financial crisis and ensuing economic turmoil could be explained. On the other, my economics classes tended to provide straightforward answers to questions that were obviously more multi-faceted, like that a minimum wage was (categorically) to be discouraged because it diminished welfare. From my political science classes I knew that it was good practice to seek out contending theories to analyze the same problem through different lenses so as to gain a deeper understanding. I wanted to learn about contending theories also in economics, but there seemed to be only one theory, so-called neoclassical economics, and its strengths and weaknesses weren’t explicitly discussed. My search for a program that satisfied my curiosity led me to look to the USA, and ultimately to the New School for Social Research, with its famous teaching of a plurality of theoretical approaches. So I went there for my graduate studies. Of course, one thing I learned soon enough was that neoclassical economics and its offshoots can be more nuanced in their assumptions and conclusions. Yet, this does not replace the more variegated approaches and points of analytical departure that the full gamut of ideas in economics (in history and present) has to offer.

CJP: Your primary research areas are in environmental and ecological economics and in economic growth. Can you briefly spell out the connection between climate change and the economy? And, more specifically, in what ways does climate change threaten economic stability and growth?

GS: Climate change is driven by greenhouse gas emissions, that are mainly caused by combusting fossil fuels and from changes in land use (think intensive agriculture or deforestation). Fossil fuels in particular have been historically tightly interlinked with economic growth. Their qualities and quantities are arguably a key factor behind the industrial revolutions in today’s rich countries. Luckily, however, while energy is a fundamental input into any economic activity, there are increasingly good alternatives to fossil fuels to supply that energy without or with much lower emissions, such as modern solar and wind energy, and a growing variety of devices compatible with the electricity they supply, such as electric vehicles and heat pumps.

At an abstract level, the interaction of economic growth and greenhouse gas emissions can be thought of as economic growth causing greenhouse gas emissions to rise. The resulting climate change “dampens” or eventually reverses economic growth through negative impacts on productivity, profitability, capital stock and human lives. More concretely, climate change poses difficult problems and threatens human wellbeing and livelihood in many ways. There are direct impacts, such as lower agricultural productivity or sea level rises. More indirect impacts intensify social problems and conflicts. To give you one example, up to two thirds of Bangladesh’s population are at risk of being impacted by sea level rise by the mid-21st century. This does not mean permanent inundation but increased exposure to flooding and salinity that make it harder to earn a living on agriculture, or risks destroying coastal non-agricultural production sites and homes. The resulting increased migration from coastal to inland communities can exacerbate social conflicts and urban poverty there, ultimately threatening social and economic stability. In the USA, up to 40 million people could be exposed to such hazards by 2100.[1] Of course, here there are much more resources available that could be used to protect communities from these impacts, so the context in which climate change impacts occur matters.

Edwin Reesink – Allegories of Wildness ~ The Name, Fame And Fate Of The Nambikwara ~ Three Nambikwara Ethnohistories Of Sociocultural And Linguistic Change And Continuity

Now online: https://rozenbergquarterly.com/allegories-of-wildness

Now online: https://rozenbergquarterly.com/allegories-of-wildness

A ‘primitive wild people’ that only Rondon could ‘pacify’, that was the reputation of wildness of these ‘savages’ around 1910. Not only that, Rondon also renamed them as the “Nambiquara” and hence, a few years later, this people acquiered its first fame in Brazil with a new name. Actually, colonial expansion and war had been part of their history since the seventeenth century. The crossing of the enormous Nambikwara territories by the telegraph line constructed by Rondon’s Mission produced, as far as known, the first real pacific contact. For those local groups most affected it proved as disastrous as all ‘first contacts’ without any preparation and substantial medical assistance. When Lévi-Strauss travelled through the region the so-called civilization had receded again. His research was very severely hampered by the historical consequences and by the fact the Indians still retained their political autonomy. Yet he has remarked they were the most interesting people he met and regarded this journey as his initiation in anthropological fieldwork. Tristes Tropiques made this people famous to a very large public and fixed another particular image of the Nambikwara. And then, in the seventies and eighties of the last century, the final assault took place by their being “before the bulldozer” (as written by the best known Nambikwara expert David Price). Only after a demographic catastrophy, permanent encirclement and great losses of territory, several Nambikwara local groups coalesced and emerged as peoples while many other local groups perished in this genocide. In effect, the so-called Nambikwara never were ‘one people’. This study explores the ethnohistory of the name, fame and fate of three of these peoples — the Latundê, Sabanê and Sararé — and dedicates some special attention to language loss and maintenance.

© Edwin Reesink, 2010, 2019 – Cover picture: Mísia Lins Reesink – Illustrations: Edgar Roquette-Pinto

© Rozenberg Quarterly 2010, 2019 – Amsterdam – ISBN 978 90 3610 173 8

- Page 2 of 3

- previous page

- 1

- 2

- 3

- next page