Définir l’islamophobie et ses manifestations politiques après les attentats de « Charlie Hebdo »

Résumé

Cet article examine les difficultés rencontrées par les définitions contemporaines de l’islamophobie, notamment celle de l’influent rapport Runnymede, face aux réactions des responsables politiques européens aux attentats de janvier 2015 à Paris. L’application de la méthode d’analyse du discours politique (ADP) à ces réactions souligne leur ambiguïté eu égard aux définitions contemporaines de l’islamophobie, et justifie de les affiner.

Mots clés

Islamophobie, rapport Runnymede, attentats de Charlie Hebdo, Union européenne, populisme.

Cet article est la version traduite et condensée de: Bogacki Mariusz, de Ruiter Jan Jaap et Sèze Romain, Defining Islamophobia and its socio-political applications in the light of Charlie Hebdo attacks in Paris, Rozenberg Quartely, 2019. URL:

http://rozenbergquarterly.com/the-charlie-hebdo-attacks-in-paris-defining-islamophobia-and-its-socio-political-applications/

Introduction

L’étude des réactions de peur ou d’hostilité à l’égard de l’islam et des musulmans a connu un tournant avec la publication du rapport Islamophobia : a challenge for us all (Runnymede Trust, 1997 et 2016), par la Commission on British Muslims and Islamophobia, créée par le Runnymede Trust (groupe de réflexion indépendant). Cette étude pionnière propose d’identifier les causes et manifestations de l’islamophobie, définie comme « une hostilité non fondée envers l’islam », une « crainte ou [une] haine de l’islam, et donc […] la peur ou l’aversion des musulmans ou de la plupart d’entre eux » (Runnymede Trust, 1997, 1), et les « conséquences d’une telle hostilité en matière de discriminations […] et d’exclusion des activités politiques et sociales » (idem, 4). Les auteurs opèrent cependant une distinction fondamentale entre « la peur phobique de l’islam [qui] caractérise des attitudes fermées, et les désaccords et critiques légitimes [qui] caractérisent des attitudes ouvertes » (idem, 4). Cette distinction repose sur huit clivages dans la façon d’appréhender l’islam et les musulmans : uniformité/diversité, séparation/interaction, infériorité/différence, adversité/partenariat, manipulation/sincérité, rejet/considération de la critique de l’Occident, justification/réprobation des discriminations, justification/réprobation de l’islamophobie (idem : 5).

Bien que ce rapport demeure une référence, il a commencé à être vigoureusement critiqué dix ans après sa publication, en particulier pour cette distinction entre « attitudes fermées » et « ouvertes ». Cette binarité tend à résumer l’attitude envers l’islam et les musulmans à de l’islamophilie ou à de l’islamophobie, tout en objectivant par effet de miroir des représentations symétriquement opposées de musulmans « bons ou mauvais », quoiqu’il en soit essentialisés, (Allen, 2010, 76). « L’islamophobie ne peut être déterminée et définie par le “type” de musulmans qui en sont victimes. Elle doit aller plus loin et tenir compte de la reconnaissance d’un “caractère musulman” réel ou perçu », car cette approche réduit l’islamophobie à un « phénomène à la fois trop simpliste et largement superficiel, défini davantage par les caractéristiques des victimes que par la motivation et les intentions des auteurs » (idem, 79-80). Or, cette approche néglige ce faisant l’existence d’un angle mort : il existe en effet des préjugés qui ne procèdent pas d’attitudes « fermées », mais qui sont la conséquence de différences de cultures, de représentations du monde et de valeurs. Les musulmans qui ne se laissent pas réduire à cette binarité sont ainsi exclus de ce traitement de l’islamophobie, et peuvent de ce fait devenir les victimes oubliées du phénomène.

Les analyses de Chris Allen invitent à considérer de nouveaux aspects des manifestations de l’islamophobie, toujours plus ambigus et complexes après le 11 Septembre, comme l’illustrent les débats contemporains sur le niqab, le multiculturalisme et les processus d’intégration religieuse et culturelle en Europe. À sa suite, divers chercheurs ont alors souligné les limites du rapport Runnymede, et proposé des alternatives. Deepa Kumar (2012, 2) et Ibrahim Kalin (2011, 11) se concentrent davantage sur la dimension racialisante du phénomène. Tahir Abbas (2011, 65), Nathan Lean et John Esposito (2012, 13) en analysent les aspects phobiques. Mohamed Nimer (2011, 78), Hedvig Ekerwald (2011) et Tahir Abbas (2011) s’intéressent aux caractéristiques culturelles et religieuses de l’islamophobie. Même Chris Allen (2010, 190) a tenté de proposer une définition alternative qui, si exhaustive soit-elle, présente une longueur et des incohérences telles qu’elle s’avère peu opérationnelle. Jocelyne Césari (2011) est sans doute celle qui acte le plus précisément ces difficultés. Elle souligne que le terme « islamophobie » est contestable parce qu’il est souvent « appliqué de manière imprécise à des phénomènes divers, allant de la xénophobie à l’antiterrorisme. Il regroupe toutes sortes de discours et d’actes en suggérant qu’ils émanent tous d’un même noyau idéologique, issu d’une peur irrationnelle (phobie) de l’islam » (idem, 21). C’est donc l’ambiguïté du terme permise par sa généralité qui rend impossible son application aux phénomènes divers qui peuvent naître des préjugés à l’égard de l’islam, mêlant préjugés et idéologies politiques variées.

Ces débats ont justifié une actualisation du rapport Runnymede, vingt ans après sa publication en 1997, dans l’objectif « d’améliorer la précision et la qualité des débats, ainsi que des politiques publiques pour lutter contre l’islamophobie » (Elahi, Khan, 2017, 1). Sur la base des réactions au rapport Runnymede, le groupe de réflexion en propose deux nouvelles définitions. La première, abrégée, définit l’islamophobie comme un « racisme antimusulman ». La seconde, plus détaillée, la définit comme « toute distinction, exclusion, restriction ou préférence à l’égard des musulmans (ou perçus comme tels) qui a pour objet ou pour effet d’annuler ou de compromettre la reconnaissance, la jouissance ou l’exercice, sur un pied d’égalité, des droits de l’Homme et des libertés fondamentales dans les domaines politique, économique, social, culturel ou tout autre domaine de la vie publique » (ibid.). Certains contributeurs à ce rapport ont également questionné la pertinence du terme « islamophobie ».

Après avoir discuté de notions de « racisme antimusulman », « préjugés antimusulmans » et « discriminations antimusulmans », Shenaz Bunglawala conclut à la nécessité de conserver le terme « islamophobie » pour deux raisons. Premièrement, il ressort des contenus médiatiques (britanniques) que le terme « islam » a plus souvent une charge péjorative que le terme « musulman », « plaçant ainsi l’appartenance perçue à un groupe au cœur de ces stéréotypes » (Bunglawala, 2017, 70). Deuxièmement, « adopter une terminologie centrée sur la victime (i.e. sur le « musulman » et non sur « l’islam ») risquerait de mener la lutte contre l’islamophobie à manquer sa cible et à oublier de prendre en considération le contexte favorable à l’uniformisation des représentations sur l’islam et les musulmans ». À revers des autres contributeurs, Shenaz Bunglawala argue en faveur de la pertinence de la dichotomie opposant attitudes « ouvertes » et « fermées », notamment au regard de la définition de l’islamophobie comme « racisme antimusulman » : « à une époque où les termes “islam”, “islamique”, “islamiste extrémiste” et “islamiste” sont fréquemment chargés de connotations péjoratives, est-il si étonnant que “l’islamophobie” conserve son pouvoir de nommer l’objet de la haine ? » (idem, 72).

Il ressort de ces débats qu’il est nécessaire de se départir des prénotions sur les victimes a priori pour examiner la pertinence des définitions de l’« islamophobie » au regard des manifestations qu’elles recouvrent dans un contexte donné. Sachant qu’elles ont crû tout en se complexifiant après le 11 Septembre, dans quelle mesure la résurgence du djihadisme depuis le milieu des années 2000 en Europe et les réactions qu’elle suscite interrogent-elles la pertinence de ce terme ? Afin d’apporter des éléments de réponse à cette question, seront examinées les réactions des responsables politiques européens à des attentats djihadistes qui les ont récemment tous interpelés : ceux de janvier 2015 à Paris. Ces évènements ont en effet concouru à renforcer les discours et pratiques discriminantes à l’endroit des musulmans dans l’Union européenne (Foundation for Political, Economic and Social Research, 2016), tout particulièrement dans le contexte des débats sur la radicalisation où les populations musulmanes font facilement figure d’ennemi intérieur (Baker-Beall et al., 2015 ; Ragazzi, 2016). Les réactions des responsables politiques à ces attentats sont en effet propres à faire apparaître les ambiguïtés liées à l’appréhension contemporaine de l’islamophobie, donc à inviter à réviser sa définition d’une part, et à réfléchir à ses implications sur les plans politique, législatif et social d’autre part.

Après avoir décrit la méthodologie appliquée pour construire le corpus des discours et les analyser (1), seront présentés les résultats de l’analyse du discours politique (2), avant de conclure par des propositions visant à cerner plus pertinemment les discours discriminatoires à l’endroit de l’islam et des musulmans.

Noam Chomsky: Trump Is Quite Capable Of An “October Surprise”

We take as axiomatic that the United States is a democracy, yet there can be no denying the fact that the country has been rapidly sliding into authoritarianism since Trump came to office, partly thanks to an antiquated mechanism known as the Electoral College. Trump’s removal of independent government watchdogs, his constant attacks on media, his divisive rhetoric, the way he has handled the coronavirus pandemic, his decision to send federal agents to crush protests, and his suggestion about postponing the November general election are but a small sample of Trump’s autocratic leadership, yet they speak volumes about the dark cloud over the U.S. In fact, it is quite conceivable that the worst is yet to come, says leading public intellectual Noam Chomsky. In this exclusive interview for Truthout, Chomsky says an “October surprise” from Trump or his cronies cannot be ruled out.

C.J. Polychroniou: Since coming to power, Trump has taken various steps to rule like an autocrat. His latest tactic is to send federal agents into cities to crush protests. Can you talk about the political aims behind Trump’s abuse of his law enforcement powers, and whether these actions have a precedent in modern U.S. history?

Noam Chomsky: The renowned economist James Buchanan, one of the leading figures of U.S.-style “libertarianism,” observed in his major work The Limits of Liberty that the ideal society should accord with fundamental human nature, which makes good sense. Then comes the next question: What is fundamental human nature? He had a very simple answer: “In a strictly personalized sense, any person’s ideal situation is one that allows him full freedom of action and inhibits the behavior of others so as to force adherence to his own desires. That is to say, each person seeks mastery over a world of slaves.”

It is not easy to find real human beings who suffer from this pathology, but Trump seems to be a good candidate…. When inspectors general begin to fulfill their duty of inquiring into the swamp of corruption he’s created, he fired them. The U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York was summarily dismissed when he made the same error, replaced by a flack for private equity.

Next in turn is the military: “The White House is intensifying an effort to hire Pentagon personnel with an undisputed allegiance to President Trump … current and former officials said.” When the Senate did not quickly confirm his choice, retired Gen. Anthony Tata, to fill “the Pentagon’s top policy job,” Trump simply appointed him without the required Senate approval. This has been standard procedure under Trump. Why bother with the legal formality of Senate confirmation?

Practices are much the same when the population dares to raise its head. They are then threatened with “ominous weapons” and “vicious dogs,” the latter a reference to the attack on civil rights protesters that aroused horror and contempt when they were used in the deep South 60 years ago. Overruling state and local officials [Trump] sent paramilitaries to assault protesters in Portland, Oregon, including the elite Border Patrol Tactical Unit (BORTAC), trained to use violence with little oversight against miserable refugees dying in the harsh Arizona desert not far from where I live.

Confronting Portland’s “Wall of Moms” with brute force does not go over too well with the general public, even arousing protests that it can’t happen here: We’re not Italy under Mussolini!

BORTAC was therefore withdrawn from Portland and returned to its mission of demonstrating that it can and doeshappen here, even if we choose not to look. A few days after leaving Portland, heavily armed BORTAC units raided a humanitarian aid station for fleeing refugees in the Arizona desert, “detaining over thirty people who were receiving medical care, food, water, and shelter from the 100+ degree heat. In a massive show of force, Border Patrol, along with BORTAC, descended on the camp with an armored vehicle, three ATVS, two helicopters, and dozens of marked and unmarked vehicles,” a No More Deaths news update reports.

There’s plenty more.

Herman Sandman – Bob Dylan: Kovvie in ‘t Zielhoes

Zo schrijft de een over een optreden van Paul Simon in Haarlem, schrijft een ander over Bob Dylan die niet in Haarlem optrad en word je gewezen op het verhaal van Herman Sandman over een fietsende Dylan in het noorden van Groningen

Zo schrijft de een over een optreden van Paul Simon in Haarlem, schrijft een ander over Bob Dylan die niet in Haarlem optrad en word je gewezen op het verhaal van Herman Sandman over een fietsende Dylan in het noorden van Groningen

Herman Sandman:

Bob Dylan, dé Bob Dylan, bracht tijdens Europese tournees wel eens een bezoekje aan het noorden van Groningen. De beroemde Amerikaanse singer/songwriter ging dan fietsen in de buurt van Noordpolderzijl. Hij vond het Hogeland mooi. De streek, het landschap, deed hem denken aan het gebied waar hij vandaan kwam, Duluth, Minnesota.

Het klonk te mooi om waar te zijn. Tot ik enkele weken later met Douwe van der Bijl in café De Drie Uiltjes zat. Douwe toonde zich een Dylan-fan en ik vertelde wat ik had gehoord.

‘Hm,’ zei hij.

Daarop kwam hij met een nog mooier verhaal.

Henk Scholte, onze Henk Scholte, in stad en ommeland bekend als verhalenverteller en folkzanger, was op een goede dag in Noordpolderzijl en stapte ’t Zielhoes binnen.

‘Hou is t?’ vroeg Henk aan de waard, de fameuze (inmiddels overleden) Siert van Warner.

‘Rustig,’ was het antwoord, ‘d’r zit allenig n gekke Amerikoan aan de bar kovvie te drinken.’

Waarop de blik van Scholte richting hoek van de bar ging en hij bijna een hartverzakking kreeg.

Bob Dylan.

Scholte begon vervolgens tegen de kroegbaas uit te varen: ‘Dat is gain gekke Amerikoan. Waist die wel wel dat is??!! Dat is Bob Dylan!!!’

Van Warner was bepaald niet onder de indruk: ‘Dat kin mie hailemoal niks schelen. As hai zien kovvie moar betoalt.’

Deze anekdote verscheen in Kleintje Boek & Wereld, uitgegeven door AFDH Uitgevers, Enschede/Doetinchem 2015.

Op zijn blog publiceerde Sandman in 2015 deze anekdote in het Engels. Met een extraatje. Als journalist wil Sandman natuurlijk weten of het verhaal wel op waarheid berustte. De eenvoudigste manier om daarachter te komen, was een berichtje aan Bob Dylan sturen.

Na een tijdje kwam het antwoord. Van meneer Dylan zelf.

[…] I remember riding past places with names like Usquert, Stitswerd en Zandeweer. We had coffee in a café with a strange owner. He just sat there. But you know, I still liked it there, because it was the first place where people didn’t gaze at me. As I was paying for the coffee I sensed that he didn’t trust me at all, not knowing who I was. And yes, you are right: next, a white bearded man came in. A fifty- year old Jesus lookalike with a hangover. ’A druid’, I guessed. […]

Het volledige verhaal is hier te vinden: http://herman-sandman.blogspot.com/2015/02/bob-dylan-loves-cycling-in-holland.html

Nu we toch bezig zijn. Er doet een verhaal de ronde dat een mevrouw een strandwandeling maakte in Oostende. Ze ontmoet een meneer. Ze raken in gesprek en gaan uiteindelijk koffiedrinken. Die meneer was Bob Dylan.

Of die mevrouw zich even wil melden.

4 augustus – Een dag later:

Riep ik gisteren op tot een speurtocht in Vlaanderen, vandaag kan iedereen weer rustig naar huis.

Een paar uur naar de oproep meldde Martin Smit dat de mevrouw in kwestie Anneke Hoftijzer heet. Zij kwam Bob Dylan in 1992 tegen in Duinkerken. Niks Oostende.

In het boek Encounters with Bob Dylan. If You See Him, Say Hello (Humble Press, San Francisco, 2000) staan een veertigtal toevallige ontmoetingen met Dylan, soms met fotografisch bewijs.

Ook het verhaal van mevrouw Hoftijzer staat in dit boek. Zij vertelt dat ze in 1992 tijdens een wandeling door Dylan werd aangesproken met de vraag of zij de jongeman die foto’s van hem maakte, wilde vragen daarmee te stoppen. In de veronderstelling dat de jongeman bij mevrouw Hoftijzer en haar zus hoorde. Als duidelijk is dat de fotograferende jongeman niet bij de twee zussen hoort, biedt Dylan zijn excuses aan en nodigt hen uit voor een drankje.

Als mevrouw Hoftijzer na 25 minuten opstaat om afscheid te nemen, staat ook Dylan op, kijkt haar aan en zegt: ‘You know, I really like you.’

In de woorden van mevrouw Hoftijzer: ‘Then he kissed both my hands and bid us farewell. I have to say, it took me several weeks to get over it.’

Dat ze vier jaar later Dylan tegen het lijf loopt tijdens een wandeling in Magdeburg is een ander verhaal.

Zie ook:

http://rozenbergquarterly.com/paul-simon-en-de-lage-landen/

http://rozenbergquarterly.com/bob-dylan-in-haarlem/

If The Fed Can Bail Out Wall Street, It Can Rescue Public Education

Public education in the U.S. has been under severe attack for many years now, thanks to the dominance of neoliberal thinking and policies across the societal spectrum. However, the coronavirus pandemic has sparked a new crisis in the nation’s public education system as a result of having created huge holes in school budgets, especially in high-poverty areas. Yet, there are ways to prevent the collapse of the public education system in the U.S., if there is a will to do so. And the rescue can come directly through the power of the Federal Reserve, according to leading progressive economist Gerald Epstein, professor of economics and co-director of the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. In this exclusive interview for Truthout, Epstein discusses how the COVID-19 crisis has exacerbated funding deficits for public education and how the Federal Reserve can step in to save schools.

C.J. Polychroniou: Is the crisis facing public education systems today simply a question of the fall-off in tax revenues on account of the pandemic?

Gerald Epstein: The shortfall is not due only to the fall-off in revenues, though that is a significant part of it. It is also because of the large extra costs that schools and universities will face to operate safely in the COVID world: the extra spacing, cleaning, masks, technology needs, and so on. No one knows exactly how much these extra costs will amount to, but various organizations have estimated them to be somewhere between $116 billion and $245 billion.

These immediate problems are made immeasurably worse in many school districts and for many colleges because of longstanding funding shortfalls facing public education, K-12 and higher education. Many school systems — and especially those in poor communities, communities of color and rural communities — have been faced with serious cut-backs for more than a decade, punctuated, only occasionally and inadequately, with compensating increases.

Indeed, since the 2007-08 Great Recession, states have been devoting even less money to public education. Is this because of the peculiarities of the current model of education, which essentially leaves matters of funding education largely to the states, or because of the domination of neoliberalism at the federal and state levels?

It is true that public education funding in the U.S. comes primarily from the states and local governments. For example, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, in 2016, 47 percent of K-12 funding came from the states, 45 percent from local governments, and only 8 percent from the federal government.

This dependence on states and local governments does contribute to inequalities in school funding among states. But, to get to your question about neoliberalism, the neoliberal turn of state governments, led primarily by Republicans, has had a devastating effect on school funding, especially for poorer communities and communities of color. As Gordon Lafer shows in his brilliant book The One Percent Solution, state and local networks funded by the Koch brothers and others were able to elect state and local officials committed to a litany of neoliberal attacks on unions, public and social goods, and the state, all in the interests of corporations. The result in many states was a cut in taxes and education funding, and a push to privatize education through charter schools and similar tricks. There was also an attack on teachers’ unions and public-school teachers’ pay.

These anti-public school measures were greatly exacerbated by the fallout from the Great Financial Crisis of 2007-2009 (GFC), which itself was largely due to neoliberal policies of financial deregulation (which exacerbated long-growing deeper problems in the economy that we have no time to discuss here).

Most states cut school funding severely when the GFC hit; and despite the long (but slow) economic expansion that occurred after the GFC and ended with the pandemic, state funding per student remains below pre-crisis levels. This is especially true of states that cut deeply during the crisis. At the local level, the collapse of the housing market led to a decline in property values in many communities. Since the primary source of local funds for public schools are property taxes, this led to lower local revenues for education. The federal government did increase funding for the states temporarily, but it was not enough and it did not last.

Just prior to the pandemic, some states had finally recovered much of the lost ground in educational expenditures, but many teacher salaries, which had been deeply cut over the neoliberal period, remained below their previous levels and were falling behind wage growth in other professions. In response, there have been a number of teachers’ strikes across the country, where teachers have demanded not only an increase in their pay, but also an increase in funding for their schools. Many of these have been successful.

Similar forces played out with respect to funding of public higher education. State funding of public higher education declined significantly over the last 20 years or more, and students and their families were more and more saddled with the bills. The huge rise in student debt, more than $1.6 trillion worth, is wreaking havoc on a generation of students that has now been confronted with two near-depression level meltdowns in the course of little more than a decade.

The important point is that all these problems were there prior to the onset of the pandemic. Now they have been greatly exacerbated.

Bob Dylan in Haarlem?

In het artikel Paul Simon en de Lage Landen van Robert-Hank Zuidinga (Rozenberg Quarterly – 3 juli j.l) viel de naam van Cobi Schreier (1922-2005). Als uitbaatster van Taverne De Waag in Haarlem organiseerde ze in 1964 het eerste optreden van Paul Simon in Nederland. Niet Paul Simon, maar Bob Dylan was de aanleiding van het bezoek dat ik haar in 2000 bracht in het Rosa Spierhuis in Laren.

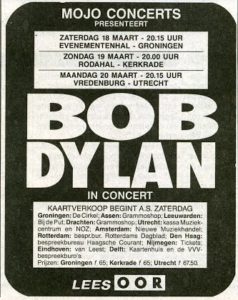

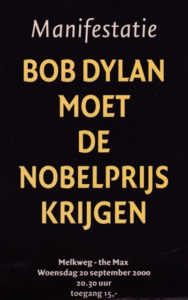

Op 27 september 2000 zou Bob Dylan weer eens optreden in Ahoy in Rotterdam. Een week eerder vond in de Melkweg de manifestatie ‘Bob Dylan moet de Nobelprijs krijgen’ plaats.

Met Huib Schreurs (De Groene), Cor Schlösser (Melkweg), Bert van der Kamp (Oor), Roel Bentz van den Berg en Theodor Holman zat ik in het organiserend comité. Het werd een lange, onvergetelijke avond, met muzikale omlijsting door o.a. Freek de Jonge, CCC Inc., Henk Hofstede, Rick de Leeuw en J.W. Roy & Band. Tal van schrijvers, dichters en journalisten hielden die avond een pleidooi waarom juist Dylan de Nobelprijs verdiende.[1]

NRC Handelsblad wilde daarom die week wel aandacht besteden aan Bob Dylan. Mijn goede vriend Ed, die wel eens een artikel schreef voor de NRC, kreeg de vraag of hij niet iets leuks wist voor een stukje op de achterpagina van die aanstaande 27 september, de dag van Dylans optreden. Ons kwam ter ore dat Cobi Schreier mogelijk een leuk verhaal over Dylan wist te vertellen. Ze zou in de jaren zestig nauw betrokken zijn geweest bij een mogelijk optreden van Dylan in Nederland. Reden dus om haar op te zoeken.

Folkcafé

In haar appartementje in het Rosa Spierhuis luisterden we die middag vijf uur lang naar een enthousiast vertellende Cobi Schreier. In min of meer chronologische volgorde  kregen we haar hele levensverhaal te horen, doorvlochten met talloze anekdotes. Plakboeken werden uit de kast getrokken, elpees en singletjes tevoorschijn getoverd en gedraaid.

kregen we haar hele levensverhaal te horen, doorvlochten met talloze anekdotes. Plakboeken werden uit de kast getrokken, elpees en singletjes tevoorschijn getoverd en gedraaid.

Voor de oorlog trad Cobi op zestienjarige leeftijd al op voor de VARA-radio. Zichzelf begeleidend op gitaar zong ze liedjes uit de Disneyfilm Sneeuwitje. Na de oorlog legde ze zich toe op oude ballades en volksliedjes en trad ze op voor de VARA en AVRO. Haar ideaal was een cafeetje te beginnen waar allerlei artiesten zouden kunnen optreden. In 1962 kreeg ze de kans De Waag in Haarlem over te nemen. Het was een klein zaaltje, er pasten hooguit honderd mensen in. Onder meer via folkicoon Pete Seeger en contacten in Londen wist ze – toen nog onbekende – folkartiesten naar Haarlem te krijgen voor optredens in De Waag zoals Paul Simon, Alex Campbell, Bert Jansch en Martin Carthy. Ze was geabonneerd op het Amerikaanse folktijdschrift Sing Out! Op die manier raakte ze vertrouwd met het repertoire van Phil Ochs en Joan Baez. Soms vertaalde ze songs om ze zelf in De Waag te kunnen spelen. Lennaert Nijgh was in De Waag vaste gast en een jonge Boudewijn de Groot kreeg de kans er op te treden.

Pete Seeger

Contact met Pete Seeger? Hoe kwam dat tot stand? In opdracht van de Ohio Recreation Service maakte ze in 1958 een EP met een aantal Nederlandse volksliedjes, bedoeld voor de Nederlandse gemeenschap in Ohio. Op de B-kant van het plaatje stonden de liedjes in Engelse vertaling. Op de een of andere manier was een exemplaar in handen van Seeger gekomen.

Toen hij in 1964 optrad voor studenten in Leiden, belde hij Cobi op met de vraag of hij in De Waag kon optreden. Op uitnodiging van Seeger bezocht ze hem later in Londen, alwaar hij haar meetroonde naar de folkclubs The Troubadour en de Singers Club. Ze zag er Ewan McColl, de aartsvader van de Engelse folkrevival, Martin Carthy & Dave Swarbrick, Bert Jansch, de Amerikaan Mark Spoelstra en Paul Simon.

Elektrische begeleiding

In 1964 trad de volstrekt onbekende Paul Simon op in De Waag. Geld voor een hotel had hij niet dus sliep hij bij Cobi thuis op de bank. Later, toen hij al wereldberoemd was, bleven ze contact houden. In de jaren zeventig trad hij op in het Concertgebouw. Hij belde Cobi en op zijn uitnodiging zat ze op de eerste rij.

Volgens Cobi zat Simon in 1965 bij haar thuis toen Art Garfunkel hem belde en hem vertelde dat hun song The Sound of Silence door producer Tom Wilson opnieuw was gemixt en uitgebracht, maar… Wilson had er zonder hun medeweten elektrische begeleiding onder gezet.

Mogelijk waren Cobi’s herinneringen bij dit verhaal in de loop der jaren toch enigszins vervaagd. Min of meer hetzelfde verhaal is namelijk bij andere bronnen eveneens te vinden.

Royal Albert Hall

En dan Bob Dylan. In 1966 regelde Cobi via haar contacten met de VARA een optreden van de Amerikaanse blues en folkartieste Odetta op de Nederlandse televisie. Ook zou ze in De Waag spelen. Bob Dylan, op dat moment op tournee in Engeland, hoorde via zijn tourmanager (die hij deelde met Odetta) de hoogte van het gage wat de VARA Odetta zou betalen. Daarop belde de tourmanager Cobi: ‘Kunnen wij met Bob Dylan naar De Waag komen?’ Enkele dagen later belde de manager af. Het ging niet door en Cobi werd afgescheept met een optreden van The Liverpool Spinners.

Omdat tourmanager Derek White duidelijk iets goed te maken had, bood hij Cobi aan het optreden van Dylan in de Royal Albert Hall op 26 mei 1966 bij te wonen. Ze mocht eerste rij zitten en na afloop van het optreden backstage komen. Het was Dylans beruchte tour waarop hij elektrisch ging: voor de pauze speelde hij een akoestische set, na de pauze elektrisch met The Hawks (later The Band) als begeleiders. Backstage was het een heksenketel. Bij de kleedkamers trof Cobi Simon Vinkenoog aan die had gedacht voor de Televizier wel even een interview met Dylan te kunnen maken. Niemand kreeg echter de kans Dylan te spreken. Hij gaf zijn gitaar af en sprintte naar een gereedstaande auto.

Speurtocht

Het stukje voor de achterpagina van de NRC ging uiteindelijk niet door. Ook bij dit verhaal bleken Cobi’s herinneringen mogelijk iets te gekleurd. Enige ongeloofwaardigheid doemde hier op: in onze speurtocht naar meer gegevens over het eventuele optreden van Dylan in Nederland, bleken data niet te kloppen en andere gegevens oncontroleerbaar. De vraag is ook of Bob Dylan tijdens deze tournee, die hem al naar Australië, Zweden en Denemarken had gevoerd, zat te wachten op een optreden in Nederland. Het concert in de Royal Albert Hall was het laatste van de tour. Twee maanden later kreeg Dylan een mysterieus motorongeluk en trok hij zich terug in Woodstock.

Het eerste concert van Bob Dylan in Nederland vond plaats op 23 juni 1978 in De Kuip in Rotterdam.

Het organiseren van onze manifestatie werd uiteindelijk beloond: in 2016 kreeg Bob Dylan de Nobelprijs voor literatuur toegekend.

Noot:

Noot:

[1] Op de manifestatie Bob Dylan moet de Nobelprijs krijgen, werden voordrachten, gedichten, pleidooien en optredens verzorgd door Bert van der Kamp, Geert Mak, Theodor Holman, Elsbeth Etty, Gijs Schreuders, Martin Bril, Wim Jansen, Edward van Vooten, Wouter van Oorschot, Simon Vinkenoog, Paul Scheffer, René Boomkens, Matthijs van Nieuwkerk, René Zwaap, Sjoerd de Jong, Freek de Jonge, Pieter Steinz, Colet van der Veen, Thomas Verbogt, Hans Righart, dj Pieter Fransen, Huub Stapel, Gerard Reve (telefonisch vanuit België), Peer de Graaf, Henk Tas, Rick de Leeuw, Ed Korlaar, Henk Hofstede, CCC Inc., J.W Roy & Band, Wouter Planteyd & Band. Vic van der Reyt presenteerde de avond.

XXL: De langste

7 (Prince and The New Power Generation), Du (Peter Maffay), Now (Dave Berry), Love (Paul Simon): korte songtitels zijn er zat. Interessanter is de vraag naar lange titels, met als hoogtepunt natuurlijk de langste songtitel uit de popgeschiedenis.

Nu lijkt lengte een objectief criterium, in tegenstelling tot persoonlijke voorkeur voor een nummer, een arrangement of het uiterlijk van een artiest. Om al te grote onenigheid te voorkomen, is het daarom wellicht wijs een paar regels aan te houden:

a. alleen letters en cijfers tellen mee, dus geen leestekens en spaties, en

b. een gedeelte tussen haakjes telt ook niet mee (waarmee een flink deel van het Verzameld Werk van Bob Dylan al afvalt).

Een voorbeeld: titelkandidaat is zeker het woordspelige If I said you had a beautiful body would you hold it against me van the Bellamy Brothers, uit 1979. Die zou op 65 tekens uitkomen, als er geen verwarring bestond over het deel na ‘body’. Dat komt in de vakliteratuur – Top 1000-lijsten, pop-encyclopedieën – namelijk in twee versies voor: wèl – dan zijn het 50 tekens – en níet tussen haakjes: 63.

De belangrijkste bron van informatie tegenwoordig, het internet, levert ellenlange lijsten van ellenlange titels op, maar die zijn zonder uitzondering van obscure nummers van obscure bands of artiesten, of zijn alleen maar bedoeld om in het Guinness Book of World Records te komen.

Interessant is trouwens, dat het Guinness Book het in de jazzhoek zoekt. Als langste wordt daar een titel genoemd van pianist en bandleader Hoagy Carmichael, die mijn eeuwige adoratie verworven heeft voor het nummer Stardust, maar die ook de bedenker blijk te zijn van de tonguetwister I’m a Cranky Old Yank in a Clanky Old Tank on the Streets of Yokohama with my Honolulu Mama Doin’ Those Beat-o, Beat-o Flat-On-My-Seat-o, Hirohito Blues uit 1942.

Het nummer van pak ‘m beet een minuut lang, werd, ondanks zijn titel van 127 tekens, nog een bescheiden hitje in de uitvoering van Bing Crosby, maar is als langste titel al lang achterhaald.

De langste telt namelijk 385 tekens en staat op het album Future Fossils (1987) van de Amerikaanse zangeres Christine Lavin:

Regretting What I Said to You When You Called Me 11:00 On a Friday Morning to Tell Me that at 1:00 Friday Afternoon You’re Gonna Leave Your Office, Go Downstairs, Hail a Cab to Go Out to the Airport to Catch a Plane to Go Skiing in the Alps for Two Weeks, Not that I Wanted to Go With You, I Wasn’t Able to Leave Town, I’m Not a Very Good Skier, I Couldn’t Expect You to Pay My Way, But After Going Out With You for Three Years I DON’T Like Surprises!! Subtitled: A Musical Apology.

Ook overdreven uitgerekt is deze, van de Zweedse groep Rednex:

The Sad But True Story Of Ray Mingus, The Lumberjack Of Bulk Rock City, And His Never Slacking Stribe In Exploiting The So Far Undiscovered Areas Of The Intention To Bodily Intercourse From The Opposite Species Of His Kind, During Intake Of All The Mental Condition That Could Be Derived From Fermentation: welgeteld 254 tekens.

Nog zo’n nummer waarvan de titel langer is dan de tekst: Long Live British Democracy Which Flourishes and Is Constantly Perfected Under the Immaculate Guidance of the Great, Honourable, Generous and Correct Margaret Hilda Thatcher. She Is the Blue Sky in the Hearts of All Nations. Our People Pay Homage and Bow in Deep Respect and Gratitude to Her. The Milk of Human Kindness, van het Londense Test Dept, komt tot 267 letters. Het staat op het album A good night out uit 1987.

De band Paracoccidioidomicosisproctitissarcomucosis uit Mexico, producent van albums als Cunnilingus (2001) en Satyriasis and Nymphomania (2002), bedacht onder meer het enigszins onvertaalbare Uroporfironogenodescarboxilandome y pustulandome con tu anorgasmita exaclorobencenosisticarial sexo traumatizante (105 tekens).

De Amerikaanse grindcore band Anal cunt wist er ook weg mee. Toch al vaardig in het vinden van provocerende titels van normale lengte – Hitler was a sensitive man, I sent concentration camp footage to Americas Funniest Home Videos en I hope you get deported -, waren de leden extra creatief als het lekker lang moest zijn. Vrouwonvriendelijkheid en homohaat inspireerden tot pareltjes van subtiliteit als Even though you’r [sic] culture oppresses women, you still suck you fucking towelhead (69 tekens), If you don’t like the Village People, you’re fucking gay (47) en I became a counselor so I could tell rape victims they asked for it (54). Hoogtepunt in deze explosie van genuanceerd mensbeeld – The only reason men talk to you is because they want to get laid, you stupid fucking cunt van het album It just gets worse (1999) – is 72 tekens lang.

Een wèl als vermakelijk bedoelde titel kwam van de hand van Barry Mann, de mannelijke helft van het songwriter-duo dat hij vormde met zijn vrouw Cynthia Weil en dat hits voorbracht als You’ve lost that lovin’ feelin’ en Saturday Night at the Movies.

In 1968 bracht hij een single uit getiteld The Young Electric Psychedelic Hippie Flippy Folk and Funky Philosophic Turned-On Groovy 12-String Band. Dat zijn 103 leestekens mèt en 89 zònder spaties.

Het was een persiflage op A simple desultory philippic (or how I was Robert McNamara’d into submission), een eveneens grappig bedoeld nummer van Paul Simon op het album Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme (1966).

Het wordt duidelijk tijd voor een aanvulling op de spelregels:

c. het moet geen – bedoelde of onbedoelde – onzin zijn (waarmee nòg een deel van het oeuvre van Bob Dylan afvalt) en

d. het moet de titel van een nummer zijn dat een hit geweest is of van een groep of artiest die bekend is of serieus genomen kan worden.

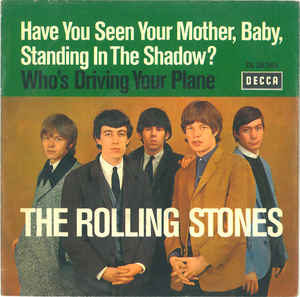

Geen bekendere bands dan the Beatles en the Stones. The Fab Four komen maximaal tot 48 tekens met Everybody’s got something to hide except me and my monkey, van het dubbel-album The Beatles (1968), beter bekend als the White Album. En the Stones raken niet verder dan de 46 tekens van Have you seen your mother, baby, standing in the shadow? uit 1966. En ook The Under Assistant West Coast Promotion Man (1965) komt tot slechts 38.

Geen bekendere bands dan the Beatles en the Stones. The Fab Four komen maximaal tot 48 tekens met Everybody’s got something to hide except me and my monkey, van het dubbel-album The Beatles (1968), beter bekend als the White Album. En the Stones raken niet verder dan de 46 tekens van Have you seen your mother, baby, standing in the shadow? uit 1966. En ook The Under Assistant West Coast Promotion Man (1965) komt tot slechts 38.

Nee, dan Pink Floyd. Several Species of Small Furry Animals Gathered Together in a Cave and Grooving With A Pict, een nummer van Roger Waters op het album Pink Floyd Works (1983), telt 76 tekens.

Even tussendoor: ook het palindroom heeft zijn weg naar de titels van popsongs gevonden. Een palindroom is een woord of naam dat van voor naar achter hetzelfde is als van achter naar voor. Een mooi voorbeeld uit de popcultuur is een album van de Amerikaanse groep Soundgarden. Die bracht in 1992 het dubbel-album Badmotorfinger uit, waarvan deel 2 onder de naam Satanoscillatemy-metallicsonatas, ook bekend als SOMMS.

Daarbij vallen Olé ELO uit 1976 van het Electric Light Orchestra (ELO) en Aoxomoxoa (1969) van The Grateful Dead in het niet. Om nog maar te zwijgen van SOS van ABBA, welke naam zelf ook weer een palindroom is.

Terug naar de langste titels. De Britse groep the Faces veroverde, toen ze al lang niet meer The Small Faces heette, het record voor langste titel van een hitsingle met het 144 c.q. 116 tekens tellende You Can Make Me Dance Sing Or Anything Even Take The Dog For A Walk, Mend A Fuse, Fold Away The Ironing Board Or Any other Domestic Short Coming. Het werd uitgebracht onder de naam Rod Stewart and the Faces – ook Ron Wood maakte daar nog deel van uit voor hij overstapte naar the Stones – en bereikte rond Kerstmis 1974 de 12de plaats in de Engelse top-40. Voor de volledigheid dient vermeld, dat de titel ook voorkomt in een versie waarbij het deel vanaf Even Take The Dog tussen haakjes staat.

Mooie voorbeelden zijn ook nog de albums 3 years, 5 months & 2 days in the life of… uit 1992 van de Amerikaanse band Arrested Development, met 42 dan wel 32 tekens, en It takes a nation of millions to hold us back (1988) van de New Yorkse hip hop-group Public Enemy: 46 tekens mèt en 36 tekens zonder spaties.

Een notoir liefhebber van lange titels is Meatloaf. Alleen al op zijn meesterproef, Bat out of hell (1977) staan You took the words right out of my mouth (Hot summer night) (32 tekens, zònder het deel tussen haakjes), All revved up with no place to go (26) en natuurlijk Paradise by the dashboard light (27). Maar ook op Bat Out of Hell II: Back Into Hell (1993) weet hij van wanten: Objects in the Rear View Mirror May Appear Closer Than They Are telt er 52, en Good Girls Go to Heaven (Bad Girls Go Everywhere).

In Nederland kom je al gauw terecht bij the Golden Earrings, want zo heetten ze nog toen. Just a little bit of peace in my heart is 30 tekens lang en I’m going to send my pigeons to the sky, van het album Golden Earring (1970), slechts 31.

Kampioen van de Lage Landen, echter, is Tröckener Kecks, bekend van frontman Rick de Leeuw. Op>TK, uit 2000, staat Zou Je Niettegenstaande De Recente Gebeurtenissen Toch Nog Een Verblijf Op Amoureus Gebied In Overweging Willen Nemen Alsjeblieft, en die telt 112 tekens. Zonder spaties!

Daarmee vergeleken is Boudewijn de Groots Ballade voor de vriendinnen van een nacht met 35 tekens maar minimaal.

Maar er is geen ontkomen aan: hoe veel van zijn titels er ook afvallen, Meester van de Lange Titel blijft Bob Dylan. Een kleine keuze uit zijn grote oeuvre, willekeurig maar in oplopende mate van onbegrijpelijkheid: I’d hate to be you on that dreadful day (van The Bootleg Series Vol 9: The Witmark Demos 1962-1964, uit 2002) – 31 letters, Stuck inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues again (op Blonde on Blonde, 1966) – 43 tekens en Talking Bear Mountain Picnic Massacre Blues – van The Bootleg Series Vols 1-3 (1991) – 38 letters

Niet zijn langste maar zeker zijn mooiste: op Highway 61 revisited (1965) staat It takes a lot to laugh, it takes a train to cry: 37 tekens.

Dat is welhaast een liedtekst op zich.