Noam Chomsky On Donald Trump And The “Me First” Doctrine

President Trump’s sudden cancellation of the upcoming denuclearization summit with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un is just the latest example of Trump’s wildly erratic approach to foreign policy.

While Trump’s domestic policies seem to be guided by clear objectives — increasing corporate profits, undoing every policy made by the Obama administration, and appeasing Trump’s anti-immigrant base — the imperatives driving US foreign policy under Trump remain something of a mystery.

In this exclusive interview, renowned linguist and public intellectual Noam Chomsky sheds light on the realities and dangers of foreign relations in the age of “gangster capitalism” and the decline of the US as a superpower.

C. J. Polychroniou: Noam, Donald Trump rose to power with “America First” as the key slogan of his election campaign. However, looking at what his administration has done so far on both the domestic and international front, it is hard to see how his policies are contributing to the well-being and security of the United States. With that in mind, can you decode for us what Trump’s “America First” policy may be about with regard to international relations?

Noam Chomsky: It is only natural to expect that policies will be designed for the benefit of the designers and their actual — not pretended — constituency, and that the well-being and security of the society will be incidental. And that is what we commonly discover. We might recall, for example, the frank comments on the Monroe Doctrine by Woodrow Wilson’s Secretary of State, Robert Lansing: “In its advocacy of the Monroe Doctrine the United States considers its own interests. The integrity of other American nations is an incident, not an end. While this may seem based on selfishness alone, the author of the Doctrine had no higher or more generous motive in its declaration.” The observation generalizes in international affairs, and much the same logic holds within the society.

There is nothing essentially new about “America First,” and “America” does not mean America, but rather the designers and their actual constituency.

A typical illustration is the policy achievement of which the Trump-Ryan-McConnell administration is most proud: the tax bill — what Joseph Stiglitz accurately called “The US Donor Relief Act of 2017”. It contributes very directly to the well-being of their actual constituency: private wealth and corporate power. It benefits the actual constituency indirectly by the standard Republican technique (since Reagan) of blowing up the deficit as a pretext for undermining social programs, which are the Republicans’ next targets. The bill is thus of real benefit to its actual constituency and severely harms the general population.

Turning to international affairs, in Trumpian lingo, “America First” means “me first” and damn the consequences for the country or the world. The “me first” doctrine has an immediate corollary: it’s necessary to keep the base in line with fake promises and fiery rhetoric, while not alienating the actual constituency. It also follows that it’s important to do the opposite of whatever was done by Obama. Trump is often called “unpredictable,” but his actions are highly predictable on these simple principles. Read more

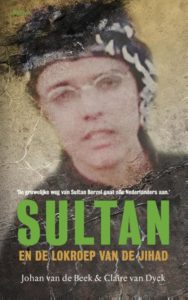

Johan van de Beek en Claire van Dyck ~ Verwerping van de Westerse waarden

Sultan en de lokroep van de jihad – Johan van de Beek en Claire van Dyck – Uitgeverij Balans – 2017 – ISBN 9789460034886 (Paperback) ISBN 9789460034893 (E-Book) & The Middle East in Europe and Europe in the Middle East (2008- I Have a dream- Felix Meritis en MEXIT)

Sultan en de lokroep van de jihad – Johan van de Beek en Claire van Dyck – Uitgeverij Balans – 2017 – ISBN 9789460034886 (Paperback) ISBN 9789460034893 (E-Book) & The Middle East in Europe and Europe in the Middle East (2008- I Have a dream- Felix Meritis en MEXIT)

In ‘Sultan en de lokroep van de jihad’ beschrijven de onderzoeksjournalisten Johan van de Beek en Claire van Dyck het radicaliseringsproces van drie jonge Maastrichtenaars, die in 2014 vertrekken naar Syrië. Sultan Berzel, oftewel Abu Abdullah al-Hollandi blaast zich kort na zijn vertrek op op het Nisourplein in Bagdad en neemt 23 mensen mee in de dood.

Sultans Koerdische vriend Rezan, die hem vergezelt, sterft op het Syrische slagveld. De derde jihad ganger, de bekeerlinge Aïcha, voorheen Lina geheten en net als Berzel en Rezan afkomstig uit Maastricht (wijk Wittenvrouwenveld) weet te ontsnappen en keert terug naar Nederland. Zij gelooft nog steeds in de jihad.

De onderzoeksjournalisten proberen te achterhalen waarom deze jonge mensen besluiten deel te nemen aan de Islamitische Staat. Hadden ze tegen kunnen worden gehouden? En is er, na het kalifaat, een blijvend gevaar van radicalisering en terreur in Nederland?

Sinds 9/11 wordt er driftig gezocht naar een patroon, een universele theorie die kan verklaren waarom jonge mensen “het oerinstinct tot overleving uitschakelen en kiezen voor een gecombineerde zelfmoord/massamoord”. Gevoelens van onrecht, discriminatie, gebroken gezinnen, zoektocht naar identiteit, armoede, eenzaamheid, opvoedingsproblemen, het verkeren in kringen waar afkeer van democratie en verwerping van westerse waarden worden gepredikt, kunnen niet alles verklaren: de zelfmoordterrorist blijft ongrijpbaar.

Terrorisme blijkt vooral een bourgeois aangelegenheid: islamitische terroristen vormen hierop geen uitzondering. De zelfmoordterrorist is vooral angstaanjagend omdat hij onvoorspelbaar is.

Via een zoektocht naar het begin, de reis terug, proberen de journalisten antwoorden te vinden. De levens van de drie jihadisten worden uitgebreid beschreven en diverse onderzoeken en auteurs worden aangehaald. Zoals de Franse jihadismekenner Gilles Kepel, die ‘de burgeroorlog binnen de islam’ benoemt, waarbij de linies niet alleen langs ideologische breukvlakken lopen, maar vaak ook tussen jong tegen oud.

—

Terror in France: The rise of Jihad in the West with Giles Kepel

Over the last two years, France has been the target of multiple brutal terrorist attacks. What caused the radicalization of young French Muslims? Why did governments across Europe fail to address it?

—

Jihad betekent ‘zware, onzelfzuchtige inspanning voor het geloof’ niet per se gewapende strijd, maar zoals gematigden zeggen, meer een strijd tegen het kwaad in de eigen ziel. Maar de meeste bronnen beschrijven de jihad als strijd tegen de ongelovigen.

Voor de drie jonge Limburgers is de oorlog tegen niet-moslims de enig correcte. Martelaarschap is het grootste offer dat je kunt brengen. Zelfmoordterroristen zijn geen zelfmoordenaars maar ‘moedjahedien’ die hebben besloten om alles en zichzelf op te offeren ten diensten van Allah. Read more

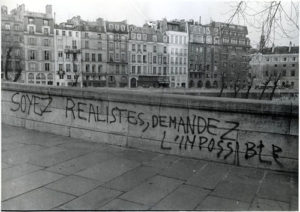

‘Be Realistic, Demand The Impossible!’ ~ How The Events Of 1968 Transformed French Society

France. Paris et Banlieue. Graffiti, bombages, inscription et affiche dans les fac et les rue autour de mai 1968

This week, 50 years ago, France was going through the biggest labour strike in its history. Two-thirds of its labour force were out in the streets demanding better working conditions. Workers had taken control of factories, set up barricades, organised sit-ins and fought off attempts by the police to disperse them. Thousands of students who had rebelled against conservative university administrations had also joined them.

By the end of the week, French President Charles de Gaulle would disappear from Paris, seeking support from the French army for a military intervention against the strikers.

Tanks, however, would not roll down the streets of Paris that year. De Gaulle would decide instead to dissolve the parliament and call for general elections. Although the crisis would subside by June, the events of May would have a major ripple effect in space and time.

Today, 50 years later, we can honestly say that what happened in May 1968 – from Paris to Prague, and from Mexico to Madrid – was the most significant political development that took place in the West during this tumultuous decade.

The 1960s witnessed the emergence of the second chapter of the civil rights movement in the US, the re-radicalisation of the labour force throughout Western Europe, women’s rights, and gay rights. But the political scene in the 1960s was marked above all else by the Vietnam War and the protests of 1968 against political elites, authoritarianism, and the bureaucratisation of everyday life.

They were spontaneous, explosive protests of rebellious spirits that changed fundamentally the political, social and cultural landscape of entire nations, although no revolution ever occurred

The May ’68 protests had the most dramatic impact in the country that had experienced one of the greatest social upheavals in western history, the French Revolution. Read more

Graham Greene And Mexico ~ A Hint Of An Explanation

In a short letter to the press, in which he referred to Mexico, Graham Greene substantially expressed his view of the world.

“I must thank Mr. Richard West for his understanding notice of The Quiet American. No critic before, that I can remember, has thus pinpointed my abhorrence of the American liberal conscience whose results I have seen at work in Mexico, Vietnam, Haiti and Chile.”

(Yours, etc., Letters to the Press. 1979)

Mexico is a peripheral country with a difficult history, and undeniably the very long border that it shares with the most powerful nation on earth has largely determined its fate.

After his trip to Mexico in 1938, Greene had very hard words to say about the latter country, but then he spoke with equal harshness about the “hell” he had left behind in his English birthplace, Berkhamsted. He “loathed” Mexico…” but there were times when it seemed as if there were worse places. Mexico “was idolatry and oppression, starvation and casual violence, but you lived under the shadow of religion – of God or the Devil.”

However, the United States was worse:

“It wasn’t evil, it wasn’t anything at all, it was just the drugstore and the Coca Cola, the hamburger, the sinless empty graceless chromium world.”

(Lawless Roads)

He also expressed abhorrence for what he saw on the German ship that took him back to Europe:

“Spanish violence, German Stupidity, Anglo-Saxon absurdity…the whole world is exhibited in a kind of crazy montage.”

(Ibidem)

As war approached, he wrote: “Violence came nearer – Mexico is a state of mind.” In “the grit of the London afternoon”, he said, “I wondered why I had disliked Mexico so much.” Indeed, upon asking himself why Mexico had seemed so bad and London so good, he responded: “I couldn’t remember”.

And we ourselves can repeat the same unanswered question. Why such virulent hatred of Mexico? We know that his money was devalued there, that he caught dysentery there, that the fallout from the libel suit that he had lost awaited him upon his return to England, and that he lost his reading glasses, among other things that could so exasperate a man that he would express his discontent in his writing, but I recall that it was one of Greene’s friends, dear Judith Adamson, who described one of his experiences in Mexico as unfair. Why?

The answer might lie in the fact that he never mentioned all the purposes of his trip.

The answer might lie in the fact that he never mentioned all the purposes of his trip.

In The Confidential Agent, one of the three books that Greene wrote after returning to England, working on it at the same time as The Power and the Glory, he makes no mention whatsoever of Mexico, but it is hard to believe that the said work had nothing to do with such an important experience as his trip there.

D, the main character in The Confidential Agent, goes to England in pursuit of an important coal contract that will enable the government he represents to fight the fascist rebels in the Spanish Civil War, though Greene never explicitly states that the country in question is Spain. The said confidential agent knows that his bosses don’t trust him and have good reason not to do so, just as he has good reason to mistrust them.

We, who know Greene only to the extent that he wanted us to know him, are aware that writers recount their own lives as if they were those of other people, and describe the lives of others as if they were their own. Might he not, then, have transferred to a character called D, in a completely different setting, his own real experiences as a confidential agent in Mexico?

Besides wishing to witness the religious persecution in Mexico first-hand, his mission might also have been to report on developments in the aforesaid country and regarding its resources -above all its petroleum- in view of the imminent outbreak of the Second World War. Read more

David Van Reybrouck ~ Zink (2016) met Mohamed El Bachiri en Een jihad van liefde (2017)

David Van Reybrouck tekent in ‘Zink’ het verhaal op van Joseph Rixen, zoon van Maria Rixen, dienstmeisje bij een fabriekseigenaar in Düsseldorf. Nadat ze van hem zwanger was geraakt en verstoten, kwam ze in het najaar 1902 terecht in Neutral Moresnet, “waar meer meisjes naar toe trokken en waar men je met rust liet”. Haar zoon groeit op in een pleeggezin, waar zijn naam van Joseph in Emil Pauly veranderd. Hij wordt speelbal van de ontwrichtende (oorlogs)geschiedenis van dit ministaatje, dat van 1816 tot 1919 het buurland was van Nederland, België en Duitsland. Gedurende een ruime eeuw bezat het een eigen vlag, een eigen bestuur, een eigen rijkswacht en een eigen nationaal volkslied in het Esperando. Ooit

moest het de eerste staat worden waar de officiële taal Esperanto was. Men vond er o.a. zink.

De jonge Emil, verwekt in Pruisen, geboren in neutraal gebied, woont sinds 1915, zonder te verhuizen, voor de volgende drie jaar in het westelijk deel van het Duitse keizerrijk. Na de wapenstilstand in 2018 wordt Brussel zijn hoofdstad; hij is pas vijftien en al aan zijn derde nationaliteit toe. Na zijn dienstplicht in het Belgische leger, trouwt Emil met Jeanne Lafèbre,

afkomstig uit Tilburg. Tussen 1934 en 1950 worden elf kinderen geboren, negen zonen en twee dochters. Ze wonen in Kelmis, waar hij bakker is.

In mei 1940 valt Hitler België binnen en annexeert het voormalige Neutraal Moresnet. Inwoners krijgen de Duitse nationaliteit en moeten onder de Wehrmacht gaan dienen. Het nazi bestuur wil Jeanne eren met het ‘Ehrenkreuz der Deutsche Mutter’, hetgeen ze weigert.

“Wat heeft zij als Nederlandse die naar België is verhuisd te maken met een Führer die beweert dat het gezin ‘het slagveld van de moeder’ is?” Als het zevende kind is geboren, eist de overheid dat hij als Duits staatsburger de voornaam en het peterschap van Hermann Wilhelm Göring krijgt. Voor de administratie wordt deze zoon Leo gedoopt, voor de kerk naar de Belgische vorst Leopold, de ouders wilden niet al te provocerend zijn. In 1943, na de nederlaag bij Stalingrad, wordt Emil Rixen ingelijfd bij de Wehrmacht; later deserteert hij. Na de bevrijding keert hij terug bij zijn gezin, maar wordt gearresteerd door

een ondergrondse verzetsorganisatie. Niet als Belg, verdacht van collaboratie, maar als Duitser in dienst van de Wehrmacht. Read more

May Day 2018: A Rising Tide Of Worker Militancy And Creative Uses Of Marx

International Workers’ Day grew out of 19th century working-class struggles in the United States for better working conditions and the establishment of an eight-hour workday. May 1 was chosen by the international labor movement as the day to commemorate the Haymarket massacre in May 1886. Ever since, May 1 has been a day of working-class marches and demonstrations throughout the world, although state apparatuses in the United States do their best to erase the day from public awareness.

In the interview below, one of the world’s leading radical economists, Jawaharlal Nehru University Professor Jayati Ghosh, who is also an activist closely involved with a range of progressive and radical social movements, discusses the significance of May Day with C.J. Polychroniou for Truthout. She also analyzes how different and challenging the contemporary economic and political landscape has become in the age of global neoliberalism, examining the new forms of class struggle that have surfaced in recent years and what may be needed for the re-emergence of a new international working-class movement.

C.J. Polychroniou: Jayati, each year, people all over the world march to commemorate International Worker’s Day, or May 1. In your view, how does the economic and political landscape on May Day, 2018, compare to those on past May Days?

Jayati Ghosh: Ever since the eruption of workers’ struggles on May 1, 1886, commemorating May Day each year reminds us of what organized workers’ movements can achieve. Over more than a century, these struggles progressively won better conditions for labor in many countries. But such victories — and even such struggles — have now become much harder than they were. Globalization of trade, capital mobility and financial deregulation have weakened dramatically the bargaining power of labor vis-à-vis capital. Perversely, this very success of global capitalism has weakened its ability to provide more rapid or widespread income expansion. As capitalism breeds and results in greater inequality, it loses sources of demand to provide stimulus for accumulation, and it also generates greater public resentment against the system.

The trouble is that, instead of workers everywhere uniting against the common enemy/oppressor, they are turned against one another. Workers are told that mobilizing and organizing for better conditions will simply reduce jobs because capital will move elsewhere; local residents are led to resent migrants; people are persuaded that their problems are not the result of the unjust system but are because of the “other” — defined by nationality, race, gender, religion, ethnic or linguistic identity. So this is a particularly challenging time for workers everywhere in the world. Confronting this challenge requires more than marches to commemorate May Day; it requires a complete reimagining of the idea of workers unity and reinvention of forms of struggle. Read more