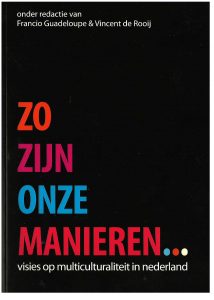

Nawoord

Deze bundel laat zien dat het uitgangspunt in de inleiding – de focus op ‘multiculturaliteit’ als een gegeven in plaats van ‘multiculturalisme’ als een ideologie – inderdaad werkt. Terecht stellen de inleiders dat de multiculturele staat van Nederland iets is waar we van uit moeten gaan.

Deze bundel laat zien dat het uitgangspunt in de inleiding – de focus op ‘multiculturaliteit’ als een gegeven in plaats van ‘multiculturalisme’ als een ideologie – inderdaad werkt. Terecht stellen de inleiders dat de multiculturele staat van Nederland iets is waar we van uit moeten gaan.

De recente protesten tegen multiculturalisme als een ideologie die het beleid in Nederland beheerst zou hebben kunnen makkelijk omslaan in een ontkenning van dat gegeven van multiculturaliteit. In lijn met de Inleiding kan gesteld worden dat die multiculturaliteit hoort bij de condition humaine – niet alleen nu, maar zover je in de geschiedenis terug kunt gaan. Het is juist het idee van één homogene cultuur dat als ideologie moet worden gezien. Dat idee mag sterk gestimuleerd zijn door het tijdperk van nationalisme, maar het kwam en komt vrijwel nooit overeen met de praktijk van het alledaagse leven. Antropologen zijn er moeizaam achter gekomen dat cultuur altijd een voortgaande vermenging van allerlei elementen is. Wel is het zo dat de opname van vreemde elementen

n sommige perioden sterker als probleem gezien wordt. Nederland maakt nu duidelijk zo’n periode door. Maar het is een illusie terug te verlangen naar een situatie van zuiverheid – ‘van vreemde smetten vrij’ zoals het heette in “Wien Neêrlands Bloed door de Ad’ren Vloeit”, (tot in de jaren dertig ons officiële volkslied) – want die situatie heeft nooit bestaan, zeker niet in Nederland.

De pragmatische verkenningen in de verschillende teksten hoe met dat gegeven van multiculturaliteit omgegaan kan worden dragen het stempel van recente antropologische discussies. Lang niet alle schrijvers zijn antropologen, maar ze lijken toch beïnvloed – sommigen misschien onbewust – door de antropologische problematisering van de notie ‘cultuur’, vanouds een centraal begrip in deze discipline. De toenemende twijfel over dat begrip onder antropologen zijn duidelijk ingegeven door wat wel de paradox van recente globaliseringsprocessen genoemd wordt: de toenemende mobiliteit van mensen, ideeën en beelden (denk aan de TV en internet) leidt niet éénzijdig tot culturele homogenisering maar eerder tot een toenemende preoccupatie met culturele verschillen. In menig opzicht heeft het begrip ‘cultuur’ zijn onschuld verloren, en dat heeft vooral na 1980 tot een herbezinning geleid binnen de antropologie op die centrale notie. Jammer genoeg blijkt het oudere ‘essentialistisch’ cultuurbegrip dat vroeger gepropageerd werd door onze discipline juist nu bredere populariteit te verwerven – ook in discussies over het Nederlandse migratiebeleid – zodat antropologen nu geconfronteerd worden met een woekering van hun oude begrippen, waarvan ze zelf moeizaam afstand genomen hebben.[i]

Deze bundel kan daarom ook gelezen worden als een poging om meer recente visies op cultuur – als constant in verandering, en gekenmerkt door voortdurende vermenging van allerlei elementen – onder de aandacht van een breder publiek te brengen. Dat lijkt hard nodig want de onhoudbare opvatting van cultuur als een vast gegeven, bepaald door een authentieke kern, blijkt in het Nederlandse migratiedebat tamelijk noodlottige gevolgen te hebben. Om maar een voorbeeld te noemen hoe anderen nu met antropologische begrippen op de loop gaan: in een bijdrage op de opiniepagina van NRC/Handelsblad (27-9-2003) refereert de filosoof Herman Philipse – nu hoogleraar in Utrecht, maar destijds nog in Leiden, en één van de leidsmannen van Hirsi Ayan – aan ‘tribaal-islamitische culturen’ die kennelijk heel het Midden Oosten en ‘islamitisch Afrika’ beheersen. Die culturen zouden bepaald zijn door overwegingen van eer en schaamte die – natuurlijk in absoluut contrast tot ‘de westerse cultuur’ – gebruik van geweld vereisen en vaste praktijken van ‘liegen en bedriegen’ ter bescherming van de eigen groep. ‘Tribaal’ was inderdaad een geliefde term van oudere antropologen, net als het idee dat Mediterrane culturen beheerst worden door ‘eer en schaamte’ (maar dit werd dan wel geacht net zo goed te gelden voor Spanje, Italië en Griekenland als voor de islamitische landen in het zuiden van dat gebied).

Door schade en schande wijs geworden zijn antropologen tegenwoordig veel voorzichtiger met zulke begrippen. Zogenaamde ‘tribale’ samenlevingen ontwikkelden zich vrijwel overal – zeker in de Arabische gebieden – in wisselwerking met staten; overal waren boven-verwantschappelijke instituten om conflicten te beslechten; en familie-eer is zeker niet alleen in het Mediterrane gebied een belangrijke overweging. Maar vooral zijn wij tot de conclusie gekomen dat een tijdloos beeld van een ‘cultuur’ als vast gegeven tot grote misverstanden leidt en het zicht blokkeert op de eindeloos variabele en creatieve manieren waarop mensen met bepaalde culturele elementen omgaan.

Read more

Zo zijn onze manieren ~ Over de auteurs

Daan Beekers (26) heeft zijn Bachelor opleiding Culturele Antropologie aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam afgerond en is nu Master student Sociale Antropologie aan de Universiteit van Oxford. Daar doet hij onderzoek naar de sociale positie van jongeren in Nigeria. Daan heeft in Nijmegen, Rotterdam en Amsterdam gewoond en bijbaantjes gehad als interviewer, winkelbediende en vuilnisman. Tussen zijn studies door heeft hij reizen gemaakt naar Senegal, Guinée, Marokko, Turkije en Oost-Europa.

Daan Beekers (26) heeft zijn Bachelor opleiding Culturele Antropologie aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam afgerond en is nu Master student Sociale Antropologie aan de Universiteit van Oxford. Daar doet hij onderzoek naar de sociale positie van jongeren in Nigeria. Daan heeft in Nijmegen, Rotterdam en Amsterdam gewoond en bijbaantjes gehad als interviewer, winkelbediende en vuilnisman. Tussen zijn studies door heeft hij reizen gemaakt naar Senegal, Guinée, Marokko, Turkije en Oost-Europa.

Yolanda van Ede is antropologe en als docente en onderzoekster verbonden aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam. Haar wetenschappelijke publicaties richten zich op uiteenlopende thema’s, van religie en ritueel, performance, familie en verwantschap, tot de zintuigen en methodologie van antropologisch onderzoek. Momenteel is ze ook haar proefschrift over een Tibetaans boeddhistisch nonnenklooster in Nepal aan het bewerken tot een roman.

Maria van Enckevort ontving haar doctoraal in Middeleeuwse Geschiedenis aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam en haar PhD in Geschiedenis aan de University of the West Indies in Jamaica. De keuze voor Jamaica was bewust om een beter inzicht te krijgen in de geschiedenis van het Caribische Gebied waar van Enckevort woont en werkt sinds 1982. Momenteel werkzaam als Dean of Academic Affairs aan de University of St. Martin (St. Maarten, Nederlandse Antillen) is van Enckevort gespecialiseerd in de volgende gebieden: multiculturalisme, Pan-Afrikanisme & Creolization, Dekolonisatie & Anti-Imperialistische Revolutionairen. Geboren en getogen in Noord-Limburg is van Enckevort nog steeds zoekende naar een erfenis die niet is vastgelegd in een testament (geleend van René Char).

Peter Geschiere (1941) is hoogleraar Antropologie van Afrika aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam. Hij doceerde antropologie en geschiedenis aan de Vrije Universiteit, de Erasmus Universiteit en de Universiteit Leiden. Daarnaast was hij visiting Professor aan de Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (Parijs / Marseille), de Universiteit van Yaounde (Kameroen), de Universiteit van Kisangani (Congo / Zaïre), de University of Witwatersrand (Johannesburg), Columbia University (New York) and New School (New York). Hij houdt zich vooral bezig met de studie van de dynamiek van lokale culturen in interactie met staatsvorming, de invloed van de markteconomie, en, meer in het algemeen, processen van globalisering. Hij publiceerde onder andere “The Modernity of Witchcraft” (1997); “Globalization and Identity – Dialectics of Flow and Closure” (1999, with Birgit Meyer); and “The Forging of Nationhood” (2003 – with Gyanendra Pandey). Momenteel bereid hij een serie conferenties voor in opdracht van de Social Sciences Research Council (New York) rondom het thema “The Future of Citizenship: New Struggles over Belonging and Exclusion in Africa and Elsewhere”. Geschiere was voorzitter van het NWO onderzoeksprogramma “Globalization and the Construction of Communal Identities”. In 2002 ontving hij de onderscheiding van “distinguished Africanist of the year” van de African Studies Association. Hij is lid van de Koninklijke Nederlandse Academie van Wetenschappen en bestuurlid van het Prince Claus Fund.

Chantal Gill’ard is lid van de Tweede Kamer voor de PvdA. Zij was parttime werkzaam als wetenschappelijk onderzoeker en promovendus bij Erasmus MC, medische ethiek en filosofie. Tot aan haar kamer lidmaatschap was zij producent bij Hof Filmprodukties. Met Rob Hof maakt zij films over globalisering(Nipkovschijf winnende productie ‘Sporen uit het Oosten’), identiteit en medisch ethische vraagstukken. Zij heeft aan de universiteit van Sheffield (UK) haar masters titel behaald in rechten en ethiek van de biotechnologie.

Read more

Solani Ngobeni ~ Scholarly Publishing: The Challenges Facing The African University Press

Abstract

Abstract

This paper seeks to examine the challenges that face the university press in Africa in general and South Africa in particular. It will start by examining the state of the university press in Africa, the state of the university press in South Africa, the challenges that face university presses, such as the declining purchasing of scholarly monographs by university libraries since the budgets of most university libraries are now spend on subscribing to expensive journals and serials, poorly paid academic staff that does not purchase scholarly books, poor teaching and research infrastructure where the course pack has replaced the monograph in the classroom, a generally under-developed market, a weakly developed reading culture, short print-runs which are not economically viable, lack of distribution hubs such as bookshops and lack of intra-Africa book trade. Whereas in the past scholarly publishers could sell between 1000 and 1500 copies of a monograph, today they sell between 200-300 copies. Since publishing small print runs is not economically viable due to economies of scale, scholarly publishers are caught between a declining market and high costs involved in publishing small print runs. It will further examine the role that research institutes and science councils play in scholarly publishing and lastly it will examine the opportunities that new modes of communications offers to scholarly publishers.

Download Paper (PDF): https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/ASC-075287668-3217-01.pdf?

ASC Working Paper 100 / 2012

Michiel O.L. van den Bergh ~ Bridging The Gap Between Bird Conservation And Sustainable Development. Perceptions And Participation Of Rural People In Burkina Faso’s Sahel Region

Introduction ~ A (research) project in the Sahel

Introduction ~ A (research) project in the Sahel

The Sahel

The Sahel is a loosely defined and not well demarcated region; it comprises the semi-arid transition region between the Sahara Desert to the north and wetter regions of sub-Saharan Africa to the south (CSELS 2010; UNEP 2007; Agnew & Chappell 1999).[i] The Sahel region is often defined by means of the number of days of the growing season or by the average annual amount of precipitation. Alternatively, the boundaries have also been drawn using latitude and longitude (Agnew & Chappell 1999). However, the boundaries are gradual and arbitrary, changing in time following weather patterns (e.g. droughts), climate changes, and land-use changes and concomitant land-cover changes (Ton Dietz, director ASCL, pers. comm. 2015). Agnew & Chappell (1999: 300) argue that “it is normally taken to be the arid West African countries from Senegal to Chad, but some also include Sudan to the East” (Figure 1.1).

The Sahel region constitutes one major ecoregion[ii] of the African continent (Brito et al. 2014). Different habitats can be found in the region, including large flat plains, gallery forests and sand dunes. The plains are mostly used for grazing and extraction of commodities (i.e. food, medicine, fodder and wood), and some smaller areas are also used for cultivation (increasing in area from north to south in the region) (Lykke et al. 2004). Traditional land-use practices such as nomadic pastoralism and agroforestry, as well as modern forestry rules, are adapted to the arid climate and erratic rainfalls (Zwarts et al. 2009; Mortimore & Adams 2001; Boffa 2000). However, this dynamic equilibrium is in jeopardy from increased agricultural and pastoralist activities, but also from overhunting, unsustainable extraction of natural resources and water overexploitation (irrigation and hydroelectric dams) (Adams et al. 2014; Brito et al. 2014; Zwarts et al. 2009).

Most, if not all, Sahel countries’ economies are strongly dependent on natural resources, but at the same time they are depleting their natural capital, making them exceptionally vulnerable (Cohen et al. 2011). Furthermore, agriculture and animal husbandry in the Sahel are highly vulnerable to climate change (Dietz et al. 2004). The region is home to a population of 100 million, and UN demographic projections for 2050 are 300 million. This rapid population growth coupled with environmental degradation and, at the same time a high dependence on the environment, is cause for grave concern. In 2012, 18 million people in the West African Sahel were suffering from malnutrition (Potts & Graves 2013). Indeed, the Sahel is sometimes labelled as one of the poorest and most environmentally degraded areas on earth (Brandt et al. 2014; CSELS 2010; Lindskog & Tengberg 1994).

The African continent is a winter ground for a quarter of the more than 500 bird species breeding in Europe, which includes between 2 and 5 billion individual birds. Especially the continent’s northern savannas, including the Sahel region, serve as a wintering ground for migrant birds. Indeed, the Sahel is an important area for migrant European birds, both for those species that spend their winter here, and for those species wintering further south on the continent that use this region as a staging area. These migrant birds are highly vulnerable to environmental change in the Sahel (Vickery et al. 2014; Zwarts et al. 2009; Jones 1995). Thus, environmental degradation in the Sahel is threatening the survival of both birds and people (Brandt et al. 2014; Ouédraogo et al. 2014; Cresswell et al. 2007).

Download Book (PDF): https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/ASC-075287668-3793-01.pdf

Notes:

[i] “Due to the large contrast in the yearly rainfall, the West African landscape gradually changes from north to south, within a distance of 600-700 km from Sahara desert to humid woodland” (Zwarts et al.2015).

[ii] “Ecoregions are relatively large units of land containing a distinct assemblage of natural communities and species, with boundaries that approximate the original extent of natural communities prior to major land-use change.” (Olson et al. 2001: 933)

ISBN: 978-90-5448-155-3 ~ © Michiel van den Bergh, 2016

Greece Under Continuous Siege: Syriza’s Disastrous Political Stance

It’s been seven years since the outbreak of the Greek debt crisis, yet Greece — the country that gave birth to democracy — is still stuck in a vicious cycle of debt, austerity and high unemployment. Three consecutive bailout programs have deprived the nation of its fiscal sovereignty, transferred many of its publicly owned assets and resources into private hands (virtually all of foreign origin), produced the collapse of the public health care system, slashed wages, salaries and pensions by as much as 50 percent, and led to a massive exodus of its skilled and educated labor force. As for democracy, it has been seriously constrained since the moment the first bailout went into effect, back in May 2010, as all governments that have come to power have pledged allegiance to the international actors and agencies behind the bailout plans — the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) — and follow closely and obediently their commands, irrespective of the needs and wishes of the Greek people.

It’s been seven years since the outbreak of the Greek debt crisis, yet Greece — the country that gave birth to democracy — is still stuck in a vicious cycle of debt, austerity and high unemployment. Three consecutive bailout programs have deprived the nation of its fiscal sovereignty, transferred many of its publicly owned assets and resources into private hands (virtually all of foreign origin), produced the collapse of the public health care system, slashed wages, salaries and pensions by as much as 50 percent, and led to a massive exodus of its skilled and educated labor force. As for democracy, it has been seriously constrained since the moment the first bailout went into effect, back in May 2010, as all governments that have come to power have pledged allegiance to the international actors and agencies behind the bailout plans — the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) — and follow closely and obediently their commands, irrespective of the needs and wishes of the Greek people.

Unsurprisingly, this includes the so-called Coalition of the Radical Left (Syriza), an opportunistic political party with a great knack for old-style cronyism and little experience in managing national affairs. Syriza has been in power for two nightmarish years now, co-governing with the extreme nationalist and xenophobic political party, The Independent Greeks (ANEL).

In the course of the last two years, Syriza, under the leadership of its populist leader Alexis Tsipras, reneged on its campaign promises to voters (ending bailouts, ending austerity and creating public work programs to reduce unemployment), and converted itself into a counterfeit copy of a social democratic party. Since the internal split with the far-left segment, Tsipras has made big-time overtures to European socialists and has attained an observer status in meetings of EU socialist leaders. In this way, Syriza has sought to fill the gap after the collapse of the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK) while signing a third bailout agreement and committing to execute international creditors’ plans for the sell-out of the country and its conversion into a neoliberal paradise for multinationals and big business interests, analogous to what took place in Latvia.

It’s true that Syriza faced incredible pressure from far stronger adversaries once it was elected, especially given the fact that the Greek state was financially bankrupt. However, the party did not need to pursue the course that it opted to follow — namely, betraying the popular mandate and converting itself into a mainstream political party in hopes of remaining in power for as long as possible. The moment Syriza’s leadership realized that it was incapable of resisting the pressures of the international creditors (the EU and IMF), it should have made a direct appeal to the Greek people by explaining the nature of the situation and the anti-democratic proclivities of the euro masters. It could have then stepped down, causing a European crisis, and turned to organizing grassroots resistance and distributive justice from the ground up. But this was never in the works: Syriza’s leadership had paid allegiance to the euro masters and the domestic corporate/financial elite even before it won the election of January 2015.

The reason why Greek governments have opted for all these years to become servants of the EU/IMF duo is quite simple: They are part of the capitalist universe and inextricably linked to the economic project of the European Union. As such, they believe there is no alternative for bankrupt Greece to bailout programs, and subsequently, to ruthless fiscal readjustment along the austerity route, coupled with a massive privatization undertaking and the end of the social state. This sad state of affairs applies even more forcefully to the current Syriza-ANEL government, which is now involved in some very awkward discussions over the completion for the assessment of the new bailout agreement. The IMF has yet to commit itself to this agreement, as it has a rather different perspective from that held by the European fiscal authorities both over the sustainability of debt and the depth of the reforms under way.

Specifically, the IMF finds the current levels of Greek public debt to be simply unsustainable (it stands at 180 percent of GDP and over 90 percent of long-term liabilities are held by public creditors). The IMF has therefore called for a sizeable debt write-off and also pushed for more reforms on all major sectors of the economy (banks, energy, labor market). In fact, the IMF wants the Greek government to commit itself via legislation to measures beyond 2018 — in other words, beyond the expiration of the new bailout agreement. The IMF contends that Greece’s debt levels will explode to much higher levels in the years (and even decades) ahead, and that the reforms proposed by the EU authorities are not specific enough, while their debt sustainability projections are ill-defined.

Read more

De mysterieuze dood van een priestervorst

De 2e man van rechts is Adranoes Lohij, de oppasser ofwel dardanel van overste Veltman, staand tussen een aantal Atjehse teukoe’s. Op zijn borst de Militaire Willems-Orde en de bronzen medaille voor Menslievend Hulpbetoon.

De tentoonstelling ‘De Laatste Batakkoning’ in 2008 in Museum Bronbeek en het daaraan gekoppelde boek gaven een helder beeld wat er voorafging aan de dood van Si Singamangaraja. Het boek, grotendeels samengesteld uit onderzoek van Harm Stevens, is voorzien van vele originele documenten die de lezer meeneemt naar een roerige tijd. Een periode waarin de laatste verzetshaarden worden uitgeschakeld en grote delen van het archipel worden onderworpen aan het koloniaal gezag.

Over de momenten van het leven van de Batakkoning bestaan verschillende lezingen. Met het ontsluiten van een oude foto, met daarop een inheemse ex-militair met onderschrift ‘Oppasser van overste Veltman’ kwamen er nieuwe feiten aan het licht.

De twaalfde Si Singamangaraja

Ompoe Pulo Batu was de twaalfde Si Singamangaraja ofwel Leeuwenvorst in erfopvolging en gold voor zijn volk als heilige. Door een sluier van mystiek die om hem heen hing en zijn hiërarchische positie in de lijn van de offerpriesters, werd hij door de westerse wereld aangeduid als de priestervorst. De in 1849 geboren priestervorst had zich net als de twee voorgaande Si Singamangaraja’s gevestigd in Bakara, gelegen ten zuidwesten van het Tobameer op Noord-Sumatra. De Bataks, gevestigd rond het Tobameer, leefden veelal autonoom en vormden midden negentiende eeuw nog niet een volk. Maar door het opdringen van het Nederlands-gouvernement en de steeds groter wordende invloed van de zending, onder aanvoering van veelal Duitse zendelingen in de laatste kwart van de negentiende eeuw, kregen de Bataks een gemeenschappelijke vijand. Dit leidde in 1883 tot een opstand onder ruim 9000 Toba-Bataks gericht tegen de westerse indringers. Door het geweld ging alles wat westers was in rook op, maar ook de bekeerde Batak-kampongs moesten het ontgelden. De schrik zat er goed in bij de Europeanen en zij velen verlieten hals over kop het Batak-gebied. De priestervorst werd gezien als leider van deze opstand en het Nederlands-gouvernement gelastte in datzelfde jaar het Nederlands Indisch Leger met een strafexpeditie tegen de priestervorst. 4 maanden lang woedde er oorlog het Batak-gebied. Nadat het Nederlands Indisch Leger op 12 augustus zijn residentie in Bakara had bereikt, was de priestervorst al met zijn gevolg gevlucht naar Lintong in de hoger gelegen oerwouden ten zuiden van het Tobameer. Bakara werd door het Nederlands Indisch Leger ‘getuchtigd’ of beter gezegd, geheel verwoest. Het zou tot 1904 duren voor er een nieuwe serieuze poging werd ondernomen om het verzet te breken. De tocht van overste Van Daalen door de Gajo, Alas en Bataklanden, maakte aan vele illusies van het verzet in de binnenlanden van Noord-Sumatra snel een eind. Met een golf van geweld trokken tweehonderd marechaussees ruim vijf maanden lang door de oerwouden van Noord-Sumatra. De marechaussees kwamen ook in het gebied van priestervorst, echter was hij net als in 1883 niet vindbaar. Met de expeditie van Hendrikus Colijn, de latere minister-president van Nederland, werd eind 1904 een nieuwe poging ondernomen. Ook toen werd er geen contact gemaakt met de priestervorst.

Brief van Si Singa Mangaradja, die regeert over de Bataks, gericht aan de heer ‘overste generaal, leider van de oorlog van de kompenie’.

‘De brief is aan u gericht omdat u oorlog voert in het land van de Bataks en mijn onderdanen gevangen heeft genomen. Maar ik heb ook woorden ontvangen van de grote heer van Medan en de resident van Tampanoeli (Batak gebied) en van de controleur, zij zeggen geen oorlog te zullen voeren tegen mij en degene waar ik over regeer.

Heb alle betrokkenen een brief gegeven dat er vrede is en ik een oorlog zal voeren tegen de kompenie. Ik zeg nu tegen de ‘overste generaal’, keert gij terug, en ga niet met mij en degene waar ik over regeer in oorlog. Het is toch niet geoorloofd om mij en mijn onderdanen lastig te vallen. Keer terug, anders overtreed u de regeles van de woorden van vrede en afspraak, die gemaakt zijn met de resident van Medan.

En als er klachten zijn over mijn onderdanen, richt u tot mij. Mijn onderdanen willen geen moeilijkheden.

Keer terug, anders overtreed u de regeles van de woorden van vrede en afspraak, die gemaakt zijn met de resident van Medan.

Zo zij het.

3 november 1904′

In de daaropvolgende jaren werden diverse kleine expedities ondernomen om de priestervorst op te sporen, echter zonder resultaat. Op 1 maart 1907 deed assistent-resident der Bataklanden een oproep aan het gouvernement. De onrust, die de ongrijpbare priestervorst met zich mee bracht, moest snel ten einde worden gebracht. Zijn oproep luidde letterlijk: “De buitengewone toestand eischt daarom buitengewone maatregelen: tydelijke verwydering van alle ongewenste elementen en de beschikbaarstelling van eenige flinke marechaussee onder een beproefde aanvoerder b.v. de kapitein Christoffel, aan wien zooveel mogelyk de vrye hand moet worden gelaten…..”.

Read more