Reshaping Remembrance ~ Language Monuments

1.

1.

The year 1975 was declared Language Year by the South African government, and 14 August was declared a public holiday in celebration of the centennial of the Genootskap van Regte Afrikaners (Society of Real Afrikaners) so that ‘people all over the country can celebrate the birthday of Afrikaans’.[i] On that day, the festivities commenced at the Voortrekker Monument in Pretoria. In memory of the eight founding members of the Genootskap van Regte Afrikaners, eight ‘language torches’ departed from the Voortrekker Monument to all corners of the Republic and to South West Africa (Namibia). In the following months, Afrikaans newspapers regularly covered the ‘Miracle of Afrikaans’, reporting on local festivities and publishing articles on the history of the Genootskap. One lasting outcome of this enthusiasm was a little-known language monument unveiled in East London on 9 September as part of a local language festival. It bears the words of a third-rate Afrikaans poet, C.F. Visser: ‘O, Moedertaal / O, soetste taal, / Jou het ek lief / bo alles’ (O mother tongue, O sweetest tongue, You I love above all). The unveiling of the huge language monument outside Paarl had been scheduled for 10 October, Kruger Day, for practical reasons: the weather was better in October than in August – the middle of the rainy Cape winter.

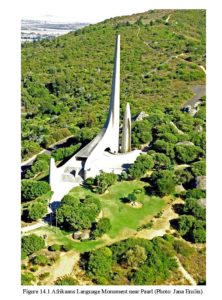

The erection of the language monument in Paarl had been in preparation since the 1940s. In 1965 a Monument Committee approved a design for a language monument by the Pretoria architect Jan van Wijk. It was to be a modernist concrete structure in the style of Le Corbusier, and according to the brief given by the committee it was to be visible from the main road and blend in with the landscape. The latter requirement was to be achieved by mixing crushed Paarl granite with the concrete. The report of the commission of experts describes the visual experience of the monument in terms of a future promenade architecturale (Le Corbusier):

The designer makes the visitor climb up stairs to reach the threshold of the entrance […] The visitor reaches a fountain and, having enjoyed the sound of the water, turns right and proceeds to the open space of the inner court. In our view, this is one of the most attractive concepts of the whole design. From this point there will be a splendid view of the main column and the buttress supporting it, an opportunity to pause for a while on one of the granite benches that will be provided and to enjoy the panoramas in the different points of the compass. […] Next to the main column, with a view on what the designer calls the ‘magical influences of Africa’, stands the smaller column that must symbolise our becoming a republic. […] A basin at the foot of both columns effectively connects them […]. We are also particularly struck by the three domes in the inner court which must remind us of the non-white elements. The inclined buttress of the inner court is reminiscent of another African motif, the ruins of Zimbabwe. We find the juxtaposition of these symbols of Africa particularly successful.[ii]

The iconography of the monument is based broadly on statements made by two important Afrikaans authors. The conspicuous main column is based on a statement made by C.J. Langenhoven in Bloemfontein in 1914, in a speech for the Suid-Afrikaanse Akademie vir Wetenskap en Kuns (South African Academy for Science and Art). Langenhoven describes the development of Afrikaans as a line reaching for heaven, a parabola of linguistic achievement. Following in the footsteps of the poet N.P. van Wyk Louw, the horizontal dimension must express the connection of a ‘lucid West’ and a ‘magical Africa’. The ‘non-white’ origins of Afrikaans are also referred to in the form of a small column, dedicated to Malay, on the stairway to the monument.

For some Afrikaners, like Loots, the founder of the Monument Committee, these symbols were an impermissible overstepping of racial boundaries. In his view, this reference to the non-white contribution to Afrikaans was ‘unnecessary’. In protest, he even threatened to disrupt the festivities with violent acts of sabotage.[iii]

2.

Early in the morning of Friday 10 October, on Kruger Day, forty thousand Afrikaners started gathering around the monument on a mountain outside the small town of Paarl. According to reports in the Cape daily Die Burger a festive mood prevailed, stimulated by the brass band of the Department of Prisons and the military band of the Cape Coloured Corps. Special provisions had been made for coloured people.

Although the terraces that had been ‘reserved’ for them were not entirely full, they nevertheless played a part in the proceedings. The Primrose Malay Choir in particular was a huge success in the amphitheatre at the foot of the monument. The choir was accompanied by a bass, guitars and ukuleles. Nine Air Force jets blazed a blue, white and orange trail – the colours of the flag – while two Afrikaner scouts hoisted the flag. At ten o’clock that night the celebrations culminated in the arrival of the language torches:

There was a stir among the crowd when hundreds of Voortrekkers [Afrikaner boy scouts] with burning torches started moving up a Paarlberg shrouded in darkness towards the amphitheatre. Contingents of eight with flags smartly handed over the route torches to the Premier [John Vorster] […] For each torch, the Navy Band played a fanfare that had been specially commissioned […] After the torch procedure, Mr Vorster delivered his address, after which the descendants [of the members of the Genootskap van Regte Afrikaners] helped to light the main torch and to declare the monument officially unveiled.[iv]

In conclusion, eight cannons fired a salvo. The eight language torches and eight cannons referred to the eight men who had founded the Genootskap van Regte Afrikaners. Those present were probably well aware of this, in view of the constant stream of articles in the press and the attention devoted to it in Afrikaans-medium schools.

The Language Monument was the last of a series of Afrikaans monuments that marked the political position of Afrikaners in the country since the end of the nineteenth in South Africa was celebrated. Read more

Reshaping Remembrance ~ And The Greatest Is … N.P. van Wyk Louw

1.

1.

In the detective novel Orion (2000) by Deon Meyer there is a number of references to N.P. van Wyk Louw. His poem ‘Die hond van God’ (God’s dog) is mentioned in the same breath as the novel Sewe dae by die Silbersteins (Seven days at the Silbersteins) by Etienne Leroux: ‘the reading and discussion of “Die hond van God” by Van Wyk Louw continued all through the night until Sunday afternoon after lunch’.[i] The purpose of this reference is to demonstrate the cultural interest of the mother of Zatopek van Heerden, a police detective and the main character in the novel, and consequently of explaining Zatopek’s exposure to intellectual stimuli. Van Wyk Louw’s poem ‘Ballade van die nagtelike ure’ (Ballad of the night-time hours) also features prominently in Orion. Three stanzas from the poem are quoted. When listening to his older mistress reciting the poem, Zatopek realizes ‘for the first time what art really is about’.[ii] His obsessional quest for the love of his life is an antidote to the dark despair which gets hold of him after every brief, casual love affair. This quest leads Zatopek to Nonnie Nagel. But precisely his passionate love for Nonnie becomes Zatopek’s Achilles’ heel; in ‘Ballade van die nagtelike ure’ he recognizes his own sad predicament: ‘I did not know that “Ballade van die nagtelike ure” would become the crystal ball of my life. I did not know how irrevocably and dramatically the morning of my life would spill me as flotsam over its rim’.[iii] In the TV serial based on Orion Van Wyk Louw is not as prominently present as in the detective novel itself anymore but at the height of their love affair Zatopek gives a book by Van Wyk Louw as a present to Nonnie.

Not only a writer of detective novels but also Afrikaans singers find inspiration in the poetry by Van Wyk Louw. To mention just a few examples: echoes of Van Wyk Louw’s poem ‘Jy was ’n kind’ (You were a child) reverberate through the song ‘Heiden Heiland’ (Heathen Saviour) from the CD Swanesang (Swan song) by the band fokofpolisiekar. The playwright Deon Opperman reworks in his poem ‘Die plukker’ (The picker) one of Van Wyk Louw’s most well-known poems: ‘Die Beiteltjie’ (The little chisel). On her CD Amanda Strydom: woman by the mirror, the singer Amanda Strydom renders Deon Opperman’s poem into song. Willie Strauss has made a CD and a theatrical production entitled Jou ma se poësie en anner gedigte (Your mother’s poetry and other poems). Some of the songs are musical settings of poems by Van Wyk Louw. In his cycle Vier liefdesgedigte (Four love poems) and in Die dobbelsteen (The die) the classical composer Cromwell Everson has put to music respectively three and two poems by Van Wyk Louw.

Cabaret is another form of popular culture. On the occasion of the one hundredth anniversary of Van Wyk Louw’s birth in 1906, the cabaret N.P. van Wyk Louw en die meisies (N.P. van Wyk Louw and the girls) was put on stage. This show was described as ‘circus with narration’.[iv] It was obviously not the intention of the producers to create great art but to provide light and somewhat saucy entertainment: ‘Thus we prepared for the audience the most scandalous episodes from his life in the most exciting ways’.[v] This approach – popular art should indeed not be too difficult – obviously relegates the more intellectually challenging poems by Van Wyk Louw to the dustbin of history. To the question ‘How do you deal with certain aesthetic mannerisms in the poetry of Louw?’ the director Albert Maritz provides the following answer: ‘We deliberately use little of his poetry and even less of his prose, and when his poetry is quoted, it is his ‘reality’ poetry. Poetry which illustrates his values in life and which he prioritized: love, beauty, his religion and politics, his love for his country’.[vi]

Does this mean that the work of Van Wyk Louw is to such an extent subjected to the ravages of time that it has become necessary to deal with it very selectively? Or has the present-day cultural climate become so shallow in comparison to Van Wyk Louw’s day and age that there is hardly any interest in or time for the more precious and intellectually challenging things in life? Die Huisgenoot (The Housemate), the popular weekly in which Van Wyk Louw published a column, cannot be compared by any stretch of the imagination with its present-day version. A lot less raunchy than Van Wyk Louw en die meisies is Klippie-nat-spu, van die haas! (Pebble-wet-spit, from the hare), a word and musical programme based on Klipwerk (Stonework) from the collection Nuwe verse (New poems) and the musical documentary made for television Big, bigger than … N.P. van Wyk Louw, which according to the Internet site of Kyknet, presents an overview of the ups and downs in the life of this giant in the history of South Africa.

Read more

Reshaping Remembrance ~ Why Have A Ghost As A Leader? The ‘De la Rey’ Phenomenon And The Re-Invention of Memories, 2006-2007

1.

1.

In an altogether unusual way, a dimension of the South African War of more than hundred years ago came to knock on the door of Afrikanerdom in 2006 and 2007, in the form of a popular song entitled ‘De la Rey’, and sung by Louis Pepler under the stage name Bok van Blerk. The song is about the exploits of the Boers during the war under the charismatic leadership of General Jacobus Hendrik (Koos) de la Rey. At the time of the centenary of the South African War in 1999-2002 there was little sign of mobilisation around bygone military events; in fact, the Afrikaners’ commemoration of the war was characterised by contemplative reflection rather than by an emotional reliving of the past.[i] However, four years later ‘De la Rey’ struck gold. Within less than a year Bok van Blerk sold the unequalled number of 200 000 CDs – an exceptional achievement in a relatively limited market. Moreover, his concerts were packed with enthusiastic fans, from the rural areas in South Africa to as far afield as America, Canada, the Netherlands and New Zealand.[ii]

For many fans the concerts were an emotional issue. Some teenagers were totally carried away: with closed eyes and hand to the heart they almost went into a trance on hearing the first chords of De la Rey. Among the enthusiastic crowds were those who regard the song as nothing less than a new national anthem.[iii] Moreover, this song did not appeal to the youth only. In Potchefstroom, where Bok van Blerk performed at the Aardklop Arts Festival, ‘little old ladies with gilt-framed reading glasses’ whispered the words in unison while ‘elderly men wearing Piet Retief beards’ jumped to their feet and heartily joined the students in song.[iv]

2.

What was Van Blerk’s intention in bringing De la Rey back to life? The media regularly questioned him about this and his answer was the same every time: it was merely about a historical figure and not politically motivated.[v] What complicates the matter, however, is that there are of course many levels of political expression. If one focuses on overt and explicit intentions linked to a programme, there is no evidence that Van Blerk and his group had any connections with organised politics before the CD was launched. But other dimensions of political involvement could indeed exist. In his description of the connection between politics and music, Goehr points out that

… by denying involvement with the political, musicians might be playing out in music their most effective political role – … in abstraction, in transcendence … In general, abstraction or transcendence has been seen to be achieved in the employment of creativity, imagination, and contemplation in what nearly twocenturies ago was referred to as ‘the free play of faculties’.[vi]

It can be argued that it is at this broad level of transcendence that the political nature of De la Rey comes to the forefront – it touches on the cultural and historical dimensions, and within this framework creates space for free association. Van Blerk’s viewpoint is that it deals with the restoration of a part of history that is in danger of being forgotten. He demarcates the terrain within which he operates: ‘Patriotism is not always political.

Just ask the Scots who still cry – even today – when they hear “Flower of Scotland” being played. It touches one’s inner being, one’s identity and culture’.[vii] From this broad, transcendental perspective the audience can then interpret the song in their own way.

De la Rey must also be read against the background of the other songs on the CD that are mostly about liquor consumption, cars, girls in bikinis and rugby (the ‘coloured’ wing Bryan Habana). These contributions are more in line with mainstream Afrikaans light music and have a different flavour. Consequently one can deduce that it was not initially the intention of Van Blerk and his group to send out a strong political message. Read more

Reshaping Remembrance ~ Boeremusiek

In the twenties and thirties traditional boeremusiek was played widely throughout South Africa. Many evenings the sounds filled houses and public places, sounded out over our land and gladdened the hearts of Boer people.[i]

In the twenties and thirties traditional boeremusiek was played widely throughout South Africa. Many evenings the sounds filled houses and public places, sounded out over our land and gladdened the hearts of Boer people.[i]

1.

On 18 January 2001, I am sitting in the lounge of Professor Stanley Glasser in his house in London. Glasser is the retired Head of Goldsmiths College, University of London, and an expatriate South African. We talk about South African composition, and the imperative for South African composers not to compose European music for South Africa, but rather South African music in which Europe could be interested because it is South African. Glasser advances the notion of a kind of composition engagée. He asks where the desire is to hear the sounds of the land, where the intimate engagement with the music of the people is to be found. And then he says:

Go to a Vastrap and see what you can do with it. Go to a Vastrap evening in Nelspruit or wherever. And see what it means, the dancing, the life, it’s all part of the music … I’m talking about if there’s a dance in Nelspruit on a Saturday night and all the farmers are coming in and the locals are coming in and there is a boereorkes. Where are you guys … do you ever roll up to that sort of thing? No. It’s the composer who has got to do that. It’s all very well to take poems by Van Wyk Louw or Leipoldt and set them. You could set it twelve tone, whole tone, keys. Whatever you like. It doesn’t matter what you use, but it’s the feeling you have that’s got to be very attached and respectful to the community as opposed to the university, I may put it that way. I used to live in Bethel, going to a dance in the local hall, with a Boereorkes playing. It was so lively and everybody was in a good mood and you’d see African children looking through the window and everybody was enjoying it in their own way.[ii]

‘You guys’. The musicologists. The academics, including and especially Afrikaners, in the suburbs and the universities. The only paper on boeremusiek at a local academic conference for music researchers ever heard by the present writer, was in Pretoria in 2002. The secretary of the local boeremusiek club addressed delegates at the invitation of Professor Chris Walton, a born Englishman who had recently arrived from Zurich to take up the Headship of the Department of Music at the University of Pretoria. Walton found boeremusiek fascinating, partly because of the significant similarities between the local sound and the folk music equivalent in Switzerland. It was a memorable occasion, not only because the paper was so interesting and the presenter very knowledgeable, but also because of the reactions of the small audience consisting of academics and music students. As the presenter demonstrated, on one of the concertinas he had brought with him, a retired English-speaking professor from the University of the Witwatersrand started moving to music, looked merrily to her neighbour and asked: ‘Where are the days?’ If the music had continued for a little while, I am convinced that she would have started to dance. The Afrikaans students and academics cringed in their seats in the lecture room. Boeremusiek is not Culture (with a capital ’C’). It is a little low, a little feeble, a little simple, a little direct, a little too close to our uncultivated needs and past.

It is therefore hardly surprising that there are no entries on boeremusiek in Jacques Malan’s South African Music Encyclopaedia. There is no reference to boeremusiek in Jan Bouws’s Komponiste van Suid-Afrika [Composers of South Africa] (1971), Bouws’s Die Musieklewe van Kaapstad 1800-1850 en sy verhouding tot die musiekkultuur van Wes-Europa [The Musical Life of Cape Town 1800-1850 and its relationship to the musical culture of Western Europe] (1966), Peter Klatzow’s Composers in South Africa Today, or in any of the twenty-five editions of the South African Journal of Musicology (SAMUS), or any of the congress proceedings of the then South African Musicological Society or the Ethnomusicology Symposium. Nothing either in Ars Nova, Muziki, The Journal of the Musical Arts in Africa or Musicus. The ‘sounds that filled houses and public places’ in the twenties and thirties clearly did not reach universities, at least not in the form of published research, research papers or documents. Academically institutionalized musicians and researchers never made this ‘place’ their own. The boeremusiek that ‘gladdened the hearts of Boer people’ is not the music of the Afrikaner intelligentsia.[iii] Read more

Reshaping Remembrance ~ Die Stem

1.[i]

1.[i]

Music is high or low. It can ascend or descend (like mountains and valleys) with an ascending run or descending scale. It is here, close to home (tonic), or there, close to relatives (relative or parallel minor/major, perhaps dominant or subdominant keys). Sometimes it moves, as is envisioned in Schoenberg’s idea of tonality, to far-off reaches of larger tonal geographies, to the furthest of such places before it returns (if it returns at all) to the known world of the tonic. Music as a kind of res extensa.[ii] Orchestration could be airy and spacious in the hands of Webern, or constructivist and muscular when done by Brahms. Music creates horizontal contours and arches through the distances between notes (intervals). These distances are determined during performance by controlling the time-space separating the end of one tone and the beginning of the next (articulation). Music is architecturally monumental in form, like a Beethoven symphony, or it is in expression and form as intimate as the salon.

We cannot approach music in language without the metaphors of place and space. Individual combinations of tones (musical ‘works’) constitute designated spaces. When these spaces become known after frequent visits, they become inhabited by cultural memory. The evocative nature of such spaces is inherent to the fact that the sentiment (emotional and/or cultural) is felt precisely, but cannot be expressed accurately in language. It is a language-resistant space. To consider Die Stem as collective memory depends on this metaphorical understanding of music in general, and of a specific work in particular. This is not a perspective that demands clarification of the song’s history. C.J. Langenhoven’s poem is only the foundation of this place. M.L. de Villiers’s melody is only the outer walls thereof and Hubert du Plessis’s official orchestration only the interior decorating.[iii]

Questions on memory and remembering and of how these things relate to this particular text, are not questions about historiography. The imagination in search of memory has to find more poetic avenues to knowledge.

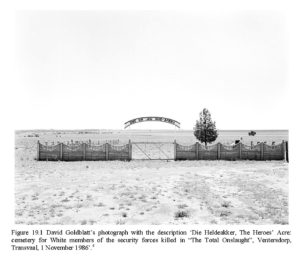

Figure 19.1 David Goldblatt’s photograph with the description ‘Die Heldeakker, The Heroes’ Acre: cemetery for White members of the security forces killed in “The Total Onslaught”, Ventersdorp, Transvaal, 1 November 1986’. [iv]

The closing phrase of Die Stem is literally displayed ‘triumphantly’ (the character indication in the music) as meaning-giving banner over this demarcated space. It lends definition to the space of the military cemetery. Does the reader hear it? The two security force members buried there are lifted up by the contour of the melody: B flat-A flat-G-B flat-C-D-E flat. The dotted rhythmical introduction to the phrase, undergirded by the secondary dominant harmony, assuages doubt, presses forward, aims towards the solution at the end of the phrase. The end is comforting as an end. It brings us home. Goldblatt’s photograph dates from 1986. It is understandable if one hears Die Stem in this time as a military song; the contours and rhythms and harmonies sound like bulwarks against the enemy, as encouragements to those who would doubt the final victory. However, for André P. Brink, Die Stem is also the song of torture in the seventies:

… every time the rebel leader is arrested, and tortured, and killed, leading to new protest, and to new martyrs; this goes on until a deadly silence remains, lasting an agonising eternity, a silence out of which, almost inaudible at first, the national anthem rises while a group of folk dancers in white masks begin to dance on the bodies of the martyrs.[v]

It is also this ‘Stem’ that, at the end of J.M. Coetzee’s Age of iron, provides the sound track to the author’s nightmarish vision of hell. ‘I am afraid’, says the dying Mrs Curran, ‘of going to hell and having to listen to Die stem (sic) for all eternity’.[vi] Die Stem that accompanies the coffin of Milla Redelinghuys into her grave at the end of Marlene van Niekerk’s Agaat has a different tenor. When the Grootmoedersdrift farm is taken into possession by the coloured woman, Agaat, who was formed by the white woman who loved and rejected her, it is Die Stem that articulates ambiguously change and continuity:

Gaat making people by the graveside sing the third verse of Die Stem: … When the wedding bells are chiming, Or when those we love depart. And then all eyes on me for: … Thou dost know us for thy children …We are thine, and we shall stand, Be it life or death to answer Thy call, beloved land! Wake up and smell the red-bait, as Pa would have said. Poor Pa with his ill-judged exclamations. Did at least make a note for my article on nationalism and music. Thys’s body language! The shoulders thrust back militaristically, the eyes cast up grimly, old Beatrice peering at the horizon. The labourers, men and women, sang it like a hymn, eyes rolled back in the head.

Word-perfect beginning to end. Trust Agaat. She would have no truck with the new anthem.[vii]

But how did historical reception develop the fascistic timbre that characterized performances and receptions of Die Stem in the 1980s, so apparent in the quotation above? Surely there was a time when Die Stem was a freedom song for Afrikaners, an alternative text for collective musical mobilization to God Save The Queen. This essay wants to connect the cited examples of fiction-mediated memories of Die Stem to the historical process represented in FAK (Federasie van Afrikaanse Kultuurvereniginge, directly translated as Federation of Afrikaans Cultural Societies) archival documents from the 1950s.

Read more

Reshaping Remembrance ~ ‘In Ferocious Anger I Bit The Hand That Controls’ – The Rise Of Afrikaans Punk Rock Music

On a night in 2006, a Cape Town’s night club, its floor littered with cigarette butts, plays host to an Afrikaner (sub)cultural gathering. Guys with seventies’ glam rock hairstyles, wearing old school uniform-like blazers decorated with a collection of pins and buttons and teamed up with tight jeans, sneakers and loose shoelaces keep one eagerly awaiting eye on the set stage and another on the short skirted girls. Before taking to the stage, the band, Fokofpolisiekar, entices the audience with the projection of their latest music video for the acoustic version of their debut hit single released two years before and entitled ‘Hemel op die platteland’.

On a night in 2006, a Cape Town’s night club, its floor littered with cigarette butts, plays host to an Afrikaner (sub)cultural gathering. Guys with seventies’ glam rock hairstyles, wearing old school uniform-like blazers decorated with a collection of pins and buttons and teamed up with tight jeans, sneakers and loose shoelaces keep one eagerly awaiting eye on the set stage and another on the short skirted girls. Before taking to the stage, the band, Fokofpolisiekar, entices the audience with the projection of their latest music video for the acoustic version of their debut hit single released two years before and entitled ‘Hemel op die platteland’.

In tune with the melancholy sound of an acoustic guitar, the music video kicks off with the winding of an old film reel revealing nostalgic stock footage of a long gone era. Well-known images make the audience feel a sense of estrangement by means of ironic disillusionment: the sun is setting in the Cape Town suburb of Bellville. Seemingly bored, the five members of Fokofpolisiekar hang around the Afrikaans Language Monument. Against the backdrop of a blue-grey sky, the well-known image of a Dutch Reformed church tower flashes in blinding sunlight. Smiling white children play next to swimming pools in the backyards of well-to-do suburbs and on white beaches while the voice of the lead singer asks:

can you tighten my bolts for me? / can you find my marbles for me? / can you stick your idea of normal up your ass? / can you spell apathy? can someone maybe phone a god / and tell him we don’t need him anymore / can you spell apathy? (kan jy my skroewe vir my vasdraai? / kan jy my albasters vir my vind? / kan jy jou idee van normaal by jou gat opdruk? / kan jy apatie spel? kan iemand dalk ’n god bel / en vir hom sê ons het hom nie meer nodig nie / kan jy apatie spel?)

And whilst the home video footage of a family eating supper in a green acred backyard is sharply contrasted with images of broken garden chairs in an otherwise empty run-down backyard, the theme of the song resonates ironically in the chorus: ‘it’s heaven on the platteland’ (‘dis hemel op die platteland’). On the dirty floor of the night club, a young white Afrikaans guy kills his Malboro cigarette and takes a sip of his lukewarm Black Label beer, watching more video images of morally grounded suburb, school and church and relates to the angry words of the vocalist:

And whilst the home video footage of a family eating supper in a green acred backyard is sharply contrasted with images of broken garden chairs in an otherwise empty run-down backyard, the theme of the song resonates ironically in the chorus: ‘it’s heaven on the platteland’ (‘dis hemel op die platteland’). On the dirty floor of the night club, a young white Afrikaans guy kills his Malboro cigarette and takes a sip of his lukewarm Black Label beer, watching more video images of morally grounded suburb, school and church and relates to the angry words of the vocalist:

‘regulate me […] place me in a box and mark it safe / then send me to where all the boxes/idiots go / send me to heaven I think it’s on the platteland’ (‘reguleer my, roetineer my / plaas my in ’n boks en merk dit veilig / stuur my dan waarheen al die dose gaan / stuur my hemel toe ek dink dis in die platteland / dis hemel op die platteland’).

As the video draws to a close, the young man sees the ironic use of the partly exposed motto engraved on the path to the Language Monument: ‘This is us’. He has never visited the Language Monument, but he agrees with what he just saw and because he feels as though he just paged through old photo albums (only to come to the disillusioned conclusion that everything has been all too burlesque) he puts his hands in the air when the band takes to the stage with the lead singer commanding:

‘Lift your hands to the burlesque […] We want the attention / of the brainless crowd / We want the famine the urgent lack of energy / We are in search of the search for something / We are empty, because we want to be’ (‘Rys jou hande vir die klug […] Ons soek die aandag / van die breinlose gehoor / Ons soek die hongersnood die dringende gebrek aan energie / Ons is op soek na die soeke na iets / Ons is leeg, want ons wil wees’. Read more