Karen Reed ~ Eigth Ways Technology Is Improving Your Health

We hear all the time about how technology is bad for us. Since the introduction of computers. Even people working on App Development have the same issues, we spend more time sitting at a desk than moving around at work. We have created this sedentary lifestyle that is causing havoc in our overall life.

We hear all the time about how technology is bad for us. Since the introduction of computers. Even people working on App Development have the same issues, we spend more time sitting at a desk than moving around at work. We have created this sedentary lifestyle that is causing havoc in our overall life.

What if I were to tell you that technology has produced benefits? Would you believe me if I said that technology is good for your health?

Most of you wouldn’t look at first. Well, you may be able to think of a couple of ways that the computer has helped, but you are still stuck on all the negatives that ‘experts’ have shared in the past. The problem with the ‘experts’ is that they are only focused on the negatives. They haven’t looked at so many of the benefits.

So, that’s what we’ll do today. We’ll consider all the ways that technology improves our health. We’ll discuss just how it has boosted results in certain areas of healthcare and what it does for us daily.

Read more: https://www.positivehealthwellness.com/fitness/8-ways-technology-improving-health/

Marlise Simons ~ Rokende spiegel – ‘Kissinger noemde mij een rood onbetrouwbaar element’

Fatou Bensouda, chief prosecutor for the International Criminal Court, in conversation with Marlise Simons, correspondent for The New York Times.

Onder de titel Rokende spiegel publiceerde Vrij Nederland* op 14 mei 1988 mijn interview met de Nederlandse journaliste Marlise Simons die ik in april van dat jaar sprak in haar toenmalige woonplaats Rio de Janeiro.

Hoewel er inmiddels ruim een kwart eeuw is verstreken is het als journalistiek tijdsdocument en als portret van een bijzondere journaliste nog steeds een goede eerste kennismaking. Bij mijn weten is dit het enige geschreven portret dat van haar is verschenen in Nederland.

Simons woont en werkt vanaf 1989 in Parijs nadat ze jarenlang voor de Washington Post en vanaf 1982 voor de New York Times, Zuid – en Midden – Amerika coverde. Vanuit Parijs deed ze verslag van de oorlogen op de Balkan en van de processen die zijn gevoerd door het Joegoslavië Tribunaal. Samen met Heikelien Verrijn Stuart publiceerde ze in 2009 : The Prosecutor and The Judge: Benjamin Ferencz and Antonio Cassese. Interviews and Writings.

Als één van de weinige vrouwen die zich moeiteloos staande houdt in de machowereld van de internationale schrijvende journalistiek, is ze te vergelijken met een andere heldin van mij, Martha Gellhorn (1908-1998) die ik in 1991 uitgebreid heb gesproken. Ze bedrijven echter twee totaal verschillende stijlen van journalistiek: is Gellhorn persoonlijk en zeer aanwezig in haar verhalen en reportages, Simons is de spreekwoordelijke buitenstaander en de beschouwer.

Marlise Simons’ eerste kennismaking met Latijns-Amerika dateert uit 1967. Na haar studie Engels en Spaans maakte ze op zevenentwintigjarige leeftijd een rondreis van drie maanden door Mexico. Ze raakte ‘zo geboeid door de hoogontwikkelde beschaving, de culturele rijkdom en de bevolking die bijna van een andere planeet afkomstig leek te zijn’ dat ze vier jaar later, vergezeld door collega en latere echtgenoot Alan Riding en een volgeladen ‘oude Volkswagen met boeken, typemachines, pillen en kort- golfapparatuur’ opnieuw naar Mexico vertrok. ‘De grote kranten hadden correspondenten zitten in Buenos Aires en Santiago, maar Midden-Amerika leek in de pers helemaal niet te bestaan. Het was dus niet zo moeilijk om daar aan het werk te komen.’

Ze vestigde zich in Mexico – Stad. Van daaruit bereisde ze het gehele Latijns–Amerikaanse continent en schreef reportages voor NRC Handelsblad, Newsweek, de Washington Post en later de New York Times. Dertien jaar later, in 1984, verhuisde ze naar Brazilië. Voor haar werk ontving ze in 1981, samen met Jacobo Timmerman, de prestigieuze Maria Moors Cabbot Prize, die elk jaar door Columbia University in New York wordt uitgereikt. Na de Pulitzer Prize (waarvoor ze in 1991 werd genomineerd, B.S.) is dit de belangrijkste journalistieke onderscheiding in de Verenigde Staten. Maar ze is de eerste om het belang van deze prijs te relativeren: ‘De journalist als held, zoals mijn collega’s Bernstein en Woodward, is voor mij uit den boze. Of zoals Oriana Fallaci die in 1968 aanwezig was bij de rellen op de Universiteit van Mexico. De volgende dag stond met grote koppen in de krant dat ze een krasje had op haar bil. Dat nieuws was belangrijker dan het leger dat het vuur opende op driehonderd mensen. Een journalist blijft altijd een doorgeefluik. Mij gaat het erom hoe ik de ene cultuur over kan brengen naar de andere, hoe moet je iets duidelijk maken voor de huiskamer in Zutphen?’

Uitgeverij Meulenhoff publiceerde in 1987 onder de titel De rokende spiegel een selectie uit de talrijke artikelen over Latijns–Amerika die Marlise Simons in de afgelopen zestien jaar schreef voor binnenlandse – en buitenlandse bladen. Tezamen geven deze ruim zestig achtergrondverhalen een breed, samenhangend beeld van de Latijns–Amerikaanse cultuur en de politieke – en maatschappelijke ontwikkelingen in de jaren zeventig en tachtig. Van de staatsgreep in Chili tot de teleurgestelde officier in Cuba, van de onderdrukte Indianenstammen in Guatemala tot het uitzichtloze bestaan in de krottenwijken van de grote steden.

Het balkon van het appartement van Marlise Simons in Rio de Janeiro biedt tussen de palmbomen op het strand een fraai uitzicht over de Atlantische Oceaan. Ook de inrichting van het appartement is het aanzien meer dan waard. De liefde die Marlise Simons voor Latijns–Amerika heeft opgevat wordt weerspiegeld in de inrichting van haar woning. Verspreid in de woonkamer staan de beeldhouwwerken die taferelen uit de rijke geschiedenis van Mexico voorstellen en aan de wanden hangen houtsnijwerken en fel gekleurde schilderijen uit Haïti.

Aan het begin van het gesprek excuseert ze zich voor het feit dat door haar jarenlange verblijf in het buitenland haar Nederlands achteruit is gegaan. Haar artikelen voor NRC Handelsblad worden uit het Engels vertaald. Wel klinkt nog zacht haar Limburgse accent door.

Is het voor een vrouwelijke journalist in dit continent moeilijker werken dan voor een man?

‘Er zitten twee kanten aan. Enerzijds voelen mannen zich minder bedreigd door een vrouwelijke journalist. Militairen vertellen je bijvoorbeeld dingen die ze niet aan mannen zouden vertellen. Een vrouw willen ze helpen en beschermen. Ze zijn nieuwsgierig. Aan het begin van de jaren zeventig was er in Latijns–Amerika veel minder ruimte voor een vrouw. Men wilde wel eens weten wat voor vreemd iemand ze voor zich hadden en men wilde dus wel praten. Anderzijds kun je als vrouw niet met mannen optrekken zoals mannen met elkaar omgaan en een pilsje gaan drinken. Maar als je buitenlandse bent dan worden de spelregels ineens anders. Wat ze van hun eigen vrouw niet zouden tolereren, dat kan van een buitenlandse wel.’ Read more

David in Ethiopia

David van Reen (1969 – 2015)

Boeken:

Anbessa’s dochter (Uitgeverij In de Knipscheer – 2016 – ISBN 9789062659302)

Het land van de verbrande gezichten (De Geus -2008 – ISBN 9789071794056)

Engelen der wrake (De Geus – 2009 – ISBN 9789044512977)

Zie ook: http://stichtinglalibela.nl/

“Op een van mijn reizen kwam ik in Woldia. Ik besloot om een wandeling te maken naar de Maryamkerk, een eind buiten het stadje. De heenweg bergop was ongeveer zes kilometer. Halverwege kwam ik een meisje tegen dat Netsannet heette. Haar naam betekent ‘vrijheid’. Gezien de blik in haar ogen zou ze geen passender naam kunnen hebben. Ze had een blikje bij zich met daarin een beetje stro en een paar eieren. Op mijn vraag wat ze met die eieren ging doen, zei ze dat ze naar de markt in Woldia ging. Ik vroeg haar waar ze woonde. Dat bleek dicht bij de Maryamkerk te zijn. Ik was verbaasd. Ze liep twaalf kilometer om twee eieren te verkopen! Haar optimisme en de levensvreugde die ze uitstraalde, maakten indruk op me. Toen ik later de foto’s die ik van Netsannet had gemaakt, afdrukte en weer zag hoe levensblij ze was, begon ik me pas af te vragen waarom wij hier op aarde zijn en of het jachtige leven dat wij westerlingen leiden, ons wel gelukkiger maakt dan Ethiopiërs. Zo ben ik met andere ogen naar deze mensen gaan kijken. Eerder al had het land me verrast door zijn schoonheid en zijn vriendelijke mensen.”

Uit: Het land van de verbrande gezichten. Leven in Ethiopië, foto’s en tekst van David van Reen, Uitg. De Geus

Imperialism Is Alive And Kicking: A Marxist Analysis Of Neoliberal Capitalism

The concept of imperialism has fallen out of the political lexicon of many leftists in the West, with some deeming the concept irrelevant for understanding the dynamics of contemporary capitalism.

Marxist economist Prabhat Patnaik has been one of the leading voices countering this trend. In A Theory of Imperialism, a book he co-authored with Utsa Patnaik, Patnaik explores how a new form of imperialism is at work in the unfolding of the capitalist system.

In this exclusive interview for Truthout, Patnaik states the case for the continuing relevance of imperialism as an analytical construct for understanding and challenging effectively the logic and dynamics of contemporary capitalism.

C.J. Polychroniou: How do you define imperialism and what imperialist tendencies do you detect as inherent in the brutal expansion of the logic of capitalism in the neoliberal global era?

Prabhat Patnaik: The capitalist sector of the world, which began by being located, and continues largely to be located, in the temperate region, requires as its raw materials and means of consumption a whole range of primary commodities which are not available or producible, either at all or in adequate quantities, within its own borders. These commodities have to be obtained from the tropical and sub-tropical region within which almost the whole of the Third World is located; and the bulk of them (leaving aside minerals) are produced by a set of petty producers (peasants). What is more, they are subject to “increasing supply price,” in the sense that as demand for them increases in the capitalist sector, larger quantities of them can be obtained, if at all, only at higher prices, thanks to the fixed size of the tropical land mass.

This means an ex ante tendency toward accelerating inflation as capital accumulation proceeds, undermining the value of money under capitalism and hence the viability of the system as a whole. To prevent this, the system requires that with an increase in demand from the capitalist sector, as capital accumulation proceeds, there must be a compression of demand elsewhere for these commodities, so that the net demand does not increase, and increasing supply price does not get a chance to manifest itself at all.

Such demand-compression occurs above all through the imposition of an income deflation on the petty producers, and on the working population in general, in the Third World. This was done in the colonial period through two means: one, “deindustrialization” or the displacement of local craft production by imports of manufactures from the capitalist sector; and two, the “drain of surplus” where a part of the taxes extracted from petty producers was simply taken away in the form of exported goods without any quid pro quo. The income of the working population of the Third World, and hence its demand, was thus kept down; and metropolitan capitalism’s demand for such commodities was met without any inflationary threat to the value of money. Exactly a similar process of income deflation is imposed now upon the working population of the Third World by the neoliberal policies of globalization.

I mean by the term “imperialism” the arrangement that the capitalist system sets up for imposing income deflation on the working population of the Third World for countering the threat of inflation that would otherwise erode the value of money in the metropolis and make the system unviable. “Imperialism” in this sense characterizes both the colonial and the contemporary periods.

Michael Dagan ~ Online Privacy Guide For Journalists 2017

Many veteran journalists, but not only these, surely noticed that we are all of a sudden bombarded again from all-over with mentions of Watergate. Books like George Orwell’s 1984 are on display at bookstores and an air of danger to freedom of speech and freedom of the press is spreading slowly like a dark cloud over the Western Hemisphere, raising old fears.

Many veteran journalists, but not only these, surely noticed that we are all of a sudden bombarded again from all-over with mentions of Watergate. Books like George Orwell’s 1984 are on display at bookstores and an air of danger to freedom of speech and freedom of the press is spreading slowly like a dark cloud over the Western Hemisphere, raising old fears.

When an American serving president accuses a former president of surveillance; when he prevents central US media outlets access – so far always granted, and taken for granted – to press conferences he holds; and when he incessantly knocks and accuses the media of being the country’s enemy number one, it isn’t surprising that memories of President Nixon surface up more with every self-pitying tweet about SNL, and that even Republican Senators such as John McCain express fear for the future of democracy.

And McCain is not alone. Many journalists whom I have spoken with recently, expressed concern for whatever lays ahead for the freedom of the press. At a time when it’s possible to express the following statement – “Donald Trump controls the NSA” – and not be held a liar, anything’s possible. Add that to the fact that recent news on CIA taught us that almost all encryption systems can be compromised, if someone has the perseverance to crack them – and you are en route to envisioning an utterly Dystopian world, where you cannot even get too comfortable laying on your sofa, in front of your own smart TV.

The good news is that it is nevertheless possible to make it difficult for anyone to try and intercept your emails, the text messages you’re sending or your phone calls. You can take measures to make the lives of those who want to uncover your sources and the information being revealed to you, much harder. Of course, the degree of effort you’re prepared to take to protect your privacy, your sources’ anonymity and your data’s safety, should be commensurate to the likelihood of a real threat, be that hacking or spying.

Read more: https://www.vpnmentor.com/blog/online-privacy-journalists/

See also: https://www.cloudwards.net/online-privacy-guide/

Global Population Ageing, The Sixth Kondratieff Wave, And The Global Financial System

Abstract

Abstract

Concerns about population ageing apply to both developed and many developing countries and it has turned into a global issue. In the forthcoming decades the population ageing is likely to become one of the most important processes determining the future society characteristics and the direction of technological development. The present paper analyzes some aspects of the population ageing and its important consequences for particular societies and the whole world. Basing on this analysis, we can draw a conclusion that the future technological breakthrough is likely to take place in the 2030s (which we define as the final phase of the Cybernetic Revolution). In the 2020s – 2030s we will expect the upswing of the forthcoming sixth Kondratieff wave, which will introduce the sixth technological paradigm (system). All those revolutionary technological changes will be connected, first of all, with breakthroughs in medicine and related technologies. We also present our ideas about the financial instruments that can help to solve the problem of pension provision for an increasing elderly population in the developed countries. We think that a more purposeful use of pension funds’ assets together with an allocation (with necessary guarantees) of the latter into education and upgrading skills of young people in developing countries, perhaps, can partially solve the indicated problem in the developed states.

Keywords: the sixth Kondratieff wave, the sixth technological paradigm, Cybernetic Revolution, population ageing, world finance, pension funds, human capital, developed countries, developing countries.

Human capital is one of the most important drivers of economic development whose contribution to the growth of production and innovations is constantly

increasing. According to the OECD definition, human capital is ‘the knowledge, skills, competencies and attributes embodied in individuals that facilitate the creation of personal, social and economic well-being’ (OECD 2001: 18; see also Kapelyushnikov 2012: 6–7). Human capital is central to debates about welfare, education, health care, and retirement. However, we think that the latter (i.e., retirement) is less frequently debated than it should be. Meanwhile, in the West the rapid population ageing actually devaluates the national human capital in every developed country. There are certain grounds to expect that if the ageing generation is not substituted by a more numerous generation of young specialists, the share of the elderly population will increase and the human capital is likely to decline.

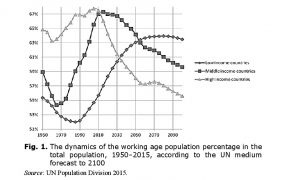

Thus, while the human capital as well as its contribution to the economic development is significantly larger in the developed countries than in the developing ones, the situation with demographic structure of human capital is different. The developing countries’ situation is significantly better at this point, and this can increasingly contribute to the economic competition between the First and Third worlds. We should also take into consideration the fact that the generation of highly educated pensioners in the developed states has increased the demands on society and they play a more active political role than the generation of uneducated ‘old men’ in the developing countries. While the West has apparently depleted its demographic dividend, many developing countries, in fact, are only in the process of its accumulation. And consequently, in this context they can get the most important advantage in the coming decades (see Fig. 1).

Thus, while the human capital as well as its contribution to the economic development is significantly larger in the developed countries than in the developing ones, the situation with demographic structure of human capital is different. The developing countries’ situation is significantly better at this point, and this can increasingly contribute to the economic competition between the First and Third worlds. We should also take into consideration the fact that the generation of highly educated pensioners in the developed states has increased the demands on society and they play a more active political role than the generation of uneducated ‘old men’ in the developing countries. While the West has apparently depleted its demographic dividend, many developing countries, in fact, are only in the process of its accumulation. And consequently, in this context they can get the most important advantage in the coming decades (see Fig. 1).

This also confirms the idea of growing convergence between the developed and developing countries that we adhere to, as the current differences in the

demographic structure and potentialities of the demographic dividend will contribute to the fact that at least in the next two decades the developing countries’ growth rates will be on average higher than those of the developed countries, although this process can proceed with certain interruptions (see Grinin 2013а, 2013b, 2013c, 2014, 2015; Korotayev and Khaltourina 2009; Khaltourina and Korotayev 2010; Korotayev, Khaltourina, Malkov et al. 2010; Korotayev and Bozhevol’nov 2010; Korotayev, Malkov et al. 2010; Malkov, Korotayev and Bozhevol’nov 2010; Malkov et al. 2010; Korotayev, Zinkina et al. 2011a; 2011b, 2012; Korotayev and de Munck 2013, 2014; Zinkina et al. 2014; Korotayev and Zinkina 2014; Korotayev, Goldstone, and Zinkina 2015; Grinin and Korotayev 2014a, 2014b, 2015а).

Read more