Efficacy of Tourism as a Tool for Local Community Development: A Case Study of Mombassa, Kenya

Having unique indigenous cultures, nature-based attractions, beautiful landscapes, and pleasant weather conditions, local communities in Africa, and other Third World countries, are increasingly being promoted and marketed in major tourist generating countries, particularly in Europe and North America, as offering immense touristic and recreational opportunities. Particularly, indigenous communities in the Third World are perceived as providing abundant opportunities for rich tourists from the North who have got the financial resources to spend in adventure and exotic recreational activities. As a consequence, an increasing number of international tourists are travelling to different tourist destinations in Africa and other less developed regions of the world. In 2001 for instance, over 28 million international tourists, mainly from Europe and North America, travelled to different destinations in Africa. It is further estimated that with the current international growth rate of the tourism industry, over 77 million international tourists will visit Africa by the year 2020 (WTO 2004).

Neo-classical economists and development experts contend that unlike factor driven technology based development, local communities in Africa and other parts of the Third World have a comparative advantage in the development of tourism and other non-technology based economic sectors. The development of tourism amongst local communities is, therefore, perceived as fitting quite well with the ‘natural process of development based on comparative advantage’ (Brohman 1996). This argument is based on the premise that local communities, particularly in Africa, should mainly specialise in primary exports, including tourism, where they have comparative advantage rather than depending on technology based economic sectors that do not conform with the principles of comparative advantage in the global market demand.

De toekomst van de relatie Nederland – Suriname IV: De hulprelatie sinds 1975

1. Inleiding

1. Inleiding

Vanaf 1975 zou de omvang en de wijze van besteding van ontwikkelingshulp alsmede de migratie vanuit Suriname de relatie tussen beide landen blijven bepalen. Over de besteding van de hulp ontstond al spoedig een officiële verhouding waarin oud zeer, achterdocht, wrevel en wrok de toonzetting bepaalden. De zich consoliderende diaspora aan beide zijden van de oceaan werd de bron van een hartelijke verhouding tussen elkaar steunende familieleden, tot uitdrukking komend in een constante stroom overmakingen en aanhoudend transatlantisch familiebezoek. De eigenaardige combinatie van hartelijke familiebanden en een stroeve hulprelatie bepaalt tot op de dag van vandaag de omgang tussen beide landen.

Dit artikel geeft een overzicht van de ontwikkelingsrelatie zoals die zich heeft ontwikkeld sinds 1975 en beoogt een evaluatie te presenteren van de economische, maatschappelijke en politieke repercussies van deze bijzondere, langdurige en omvattende bilaterale en overwegend intergouvernementele hulprelatie, Sectie 2 gaat in op de onderhandelings- en uitvoeringscultuur waarbinnen hulpprojecten en programma’s werden geformuleerd en vorm kregen. Sectie 3 presenteert een balans van de resultaten die werden bereikt en onderscheidt daarbij een groot aantal van de belangrijkste projecten en programma’s die gedurende deze lange periode tot stand werden gebracht. Sectie 4 geeft aan op welke wijze de bilaterale relatie zich ontwikkelde tot een belaste relatie, en wat daar de kenmerken en uiteindelijke gevolgen van zijn geweest. Tenslotte wordt in Sectie 5 naar de toekomst gekeken. Read more

De toekomst van de relatie Nederland – Suriname V: De verdragsrelatie in een breder perspectief

1. Inleiding

1. Inleiding

De resultaten van de samenwerking tussen Nederland en Suriname worden vaak geïsoleerd beoordeeld, zonder in beschouwing te nemen welke ontwikkelingen zich in dezelfde tijd elders voordeden. Dit stuk plaats de samenwerking in een breder kader en komt met nuanceringen op de soms harde oordelen die over de hulp worden geveld. In Sectie 2 wordt ingegaan op het bijzondere karakter van de bilaterale verdragsrelatie in vergelijking met de meer gangbare wijze waarop internationaal en ook door Nederland hulprelaties worden aangegaan. Belangrijke component van de bilaterale hulprelatie is het beleidsoverleg, dat mede een weerspiegeling is van achterliggende trends in het denken over ontwikkelingsvraagstukken en ontwikkelingsbeleid, zoals wordt uiteengezet in Sectie 3. Conditionaliteiten spelen in veel hulpprogramma’s een cruciale rol en zijn vaak onderwerp van controverse en conflict. Sectie 4 maakt onderscheidt tussen ex-ante– en ex-post-conditionaliteiten en zet de daaraan verbonden consequenties voor de hulprelatie uiteen. Het project PARWAT in Paramaribo dient ter illustratie daarvan. Sectie 5 gaat in op het rapport Een belaste relatie en plaatst daar een aantal nuanceringen bij. Tenslotte wordt in de laatste sectie een suggestie gedaan voor toekomstige samenwerking. Read more

De toekomst van de relatie Nederland – Suriname: Video Suriname 1973-1982 – Deel 1

Voor de overige vier delen: http://www.youtube.com/user/jessicadikmoetnl/videos

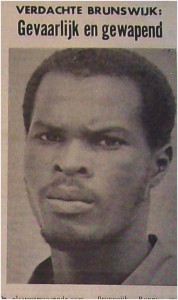

The making of Ronnie Brunswijk in Nederlandse media

‘De binnenlandse oorlog in Suriname was als oorlogsverslaggever een van mijn mooiste reizen. Het was een bijna zwart-wit verhouding. The good guy tegen de bad guy’, zei Arnold Karskens, doorgewinterd oorlogsjournalist, tijdens de presentatie van zijn boek Rebellen met een reden eind oktober 2009 tegen de Wereldomroep. In die Binnenlandse Oorlog (1986-1992) – zoals de strijd tussen Ronnie Brunswijk en voormalig bevelhebber van het Nationaal Leger Desi Bouterse genoemd wordt – was Bouterse in de ogen van Karskens the bad guy. ‘Want Desi Bouterse was natuurlijk verantwoordelijk voor veel doden in Suriname.’ De strijd van Brunswijk was wat Karskens betreft ‘een rechtmatige strijd tegen de dictatuur’ [i] En vóór terugkeer van de democratie. Niet iedereen zal het met Karskens eens zijn geweest. Sommigen – ook buiten de kring van Bouterse-getrouwen – menen dat de Binnenlandse Oorlog het democratiseringsproces dat kort daarvoor in gang was gezet, juist verstoorde![ii]

Met zijn uitspraak bevestigde Karskens het beeld dat er bestaat van partijdigheid van het Nederlandse journaille bij de Binnenlandse Oorlog. Tijdens de gesprekken die ik voerde voor mijn boek Suriname na de Binnenlandse Oorlog kreeg ik het verwijt vaak te horen. Zo wilde ex-commandant Henk Roy Matui – Mato – wel praten over de reden waarom de Tucayana Amazones zich mengden in de strijd tussen Bouterse en Brunswijk, maar niet voordat hij zijn hart had gelucht. Hij vond: de Nederlandse media maakten Brunswijk ‘groter’ dan hij was (De Vries 2005:133).

When Congo Wants To Go To School – Part III – Acti Cesa

A few years ago Catherine Coquery-Vidrovitch wrote about the results of the educational system in the Belgian Congo that “(This) in depth work concerning mentalities was started to be felt from 1945. [i] We have tried to approach the issue of the effects of the missionary education from two angles. On the one hand, on the basis of the written testimonies that can be found, from which it is apparent how the Congolese reacted, how they acted and what they thought about that education. Publications in which the opinion of the Congolese pupils and former pupils can be found were sought as contemporary sources. Concrete, extensive and detailed research was carried out into one of those publications, La Voix du Congolais. On the other hand, it is possible to make use of memories. These are preferably the memories of the people themselves. A number of interviews with the Congolese helped complement the very sparse literature available in this regard.

A few years ago Catherine Coquery-Vidrovitch wrote about the results of the educational system in the Belgian Congo that “(This) in depth work concerning mentalities was started to be felt from 1945. [i] We have tried to approach the issue of the effects of the missionary education from two angles. On the one hand, on the basis of the written testimonies that can be found, from which it is apparent how the Congolese reacted, how they acted and what they thought about that education. Publications in which the opinion of the Congolese pupils and former pupils can be found were sought as contemporary sources. Concrete, extensive and detailed research was carried out into one of those publications, La Voix du Congolais. On the other hand, it is possible to make use of memories. These are preferably the memories of the people themselves. A number of interviews with the Congolese helped complement the very sparse literature available in this regard.

When considering this theme, the original boundaries of the research subject were slightly deviated from. The research subject was deviated from as regards the material, as the

interviews are situated both within but also partly outside the mission area of the MSC. The existing research results that were consulted and used also relate to areas outside the Tshuapa region. Moreover, the research subject was deviated from with regard to content due to the conclusion that research into the effects of education is inextricably connected to the “memory” of the colonial period. Consequently, it seemed interesting to us to take the memories of former pupils into account. That has the undeniable advantage that the image drawn may be confronted to a certain extent with the memories of the Congolese.

In the previous four chapters, written material was primarily collected that spoke about the events that took place in and around the school in the mission area of the MSC. The image created as a result is perhaps still not very clear but the outlines may be discerned. Naturally coloured by all the information I collected myself as a researcher and undoubtedly also coloured by the information I did not collect, I did not think it very useful to consider all that material again in a conclusive chapter and to attempt to distil a summarising image from that.

I will therefore restrict my conclusion to an indication of the image drawn and the formulation of a number of considerations regarding the way in which this past is handled and the role this research may hopefully play in it.

NOTE:

[i] Tshimanga, C. (2001). Jeunesse, formation et société au Congo/Kinshasa 1890-1960 . Paris: L’Harmattan. p. 5 (préface). [original quotation in French]