A Green New Deal Is Actually More Affordable In the Long Term Than Fossil Fuels

With global warming representing humanity’s greatest existential crisis, reducing carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions to zero by 2050, as recommended by the 2018 report of Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), should be one of the U.S.’s most urgent priorities. We need a Green New Deal now.

In examining the urgency of this necessity, we must recognize the current state of climate response in this country and around the world. Five years ago, the Paris Agreement on climate change was adopted. It was called “historic” because all members of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change committed themselves to limiting global warming below 2 — and ideally to 1.5 — degrees Celsius (2°C) compared to pre-industrial levels. Yet progress toward that goal has been slow, where it has happened at all.

We are just emerging from the Trump era, when the former leader of the world’s largest economy and of the most powerful nation/empire in history not only questioned the science around climate change and withdrew the United States from the Paris Agreement, but also dismantled scores of environmental regulations and even reversed an Obama-rule on methane emissions — even though methane, the natural ingredient in natural gas, is 84 times more potent than carbon dioxide.

While some investors are shifting away from the fossil fuel economy, close to 85 percent of global primary energy still comes from coal, oil and gas. And no one should be led to believe that the temporary decline of greenhouse gas emissions during the COVID pandemic will last once the virus is brought under control.

As a matter of fact, while fossil fuel production needs to be decreased by roughly 6 percent between 2020 and 2030 in order for countries to remain in line with the 1.5°C target, governments are planning instead to increase fossil fuel production by an average of 2 percent annually, according to a report released by the Stockholm Environment Institute, together with the UN Environment Program and other leading research institutions.

In addition, between 2016 and 2020, the world’s largest banks have put collectively $3.8 trillion into fossil fuel companies, a development which may perhaps be the best indication of the toothless design behind the Paris climate accord and why it is naïve and dangerous to rely on the “invisible hand” of the market either for economic transformation or for a solution to the problem of climate change. Indeed, as climate economist Nicholas Stern put it more than a decade ago, greenhouse gas emissions “represent the biggest market failure the world has seen.”

Meanwhile, climate change denial remains prevalent, including among national leaders such as Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil and former President Trump.

The return of the U.S. to the Paris climate agreement, combined with Joe Biden’s executive order which explicitly recognizes that the United States and the world face “a profound climate crisis” and that tackling global warming will be a central objective in U.S. foreign policy and national security, are surely welcome news, but the efforts to combat global warming need to intensify. We need a well laid out plan for a swift transition away from fossil fuel and towards clean and renewable energy systems. As the World Meteorological Organization warned in a report issued back in March 2020, “time is fast running out.”

The Green New Deal is the best proposal we have to decarbonize the economy and protect the planet from the dire consequences of global warming, including hotter heat waves, increased tropical storms and floods, prolonged droughts, loss of freshwater, flooding of coastal areas, large-scale migration and potentially, eventually, human extinction.

The Green New Deal is portrayed as unaffordable, but in fact, it is financially manageable, especially given what is at stake if we fail to stop irreversible and disastrous changes to our climate system. According to leading economist Robert Pollin of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, the global economy must spend an average of $4.5 trillion per year (or 2.5 percent of global GDP) between 2024-2050 in clean energy investments in order to hit the 2050 IPCC emissions reduction target. This estimate is corroborated by the latest study from the International Renewable Energy Agency, which puts the figure that needs to be invested for the energy transition at $4.4 trillion per year.

In addition to staving off the worst effects of global warming, the transition to a clean energy economy through the Green New Deal will also boost economic growth by creating millions of new, well-paying jobs in manufacturing, construction, energy, sustainable agriculture, engineering, and other sectors of the economy.

Pollin has shown in various published studies that the transition to clean energy systems will prove economically beneficial, expanding job opportunities across the economic spectrum. With respect to the United States, the employment opportunities that will be generated from the infrastructure programs designed to move the economy towards clean energy systems amount to millions of jobs.

Additionally, a transition to clean and zero-emission energy systems will substantially reduce energy costs and health care expenses. According to Mark Jacobson, one of the authors of a Green New Deal energy study published in the journal One Earth, the world will spend around $13 trillion per year on energy by 2050 if we are still reliant on fossil fuels, but the cost drops to $6.8 trillion if we are using clean, renewable energy. According to the same study, trillions of dollars will also be saved each year in health costs, because the Green New Deal would reduce toxic air and water pollution, which are now responsible for millions of deaths annually.

However, powerful economic interests and lack of political will stand in the way of a shift away from fossil fuels and toward a green economy. These two determinants are intertwined and must be addressed simultaneously if civilization is to continue to exist in any recognizable form.

The fossil fuel industry — which has been fully aware of the damage that its products cause to the environment but managed until fairly recently to hide this fact from the public — should be treated like a pariah and phased out. Banks and international financial institutions should be banned from funding fossil fuel production. “Environcide,” the deliberate destruction of the environment, should be recognized by international law as a crime against humanity, as Emmanuel Kreike has argued in his new book, Scorched Earth: Environmental Warfare as a Crime against Humanity and Nature. In addition, fossil fuel subsidies, which are estimated to run into hundreds of billions of dollars annually, must end.

In sum, all financial and political links to the fossil fuel industry must be severely disrupted if any serious progress is to be made toward building a green economy on a global scale.

The struggle to save the planet is the biggest challenge that has ever faced humanity, and time is running out. In this century, we will find out if our species is equipped to overcome its own narrow interests and work toward achieving a sustainable future not just for us, but for all life on planet Earth.

—

Copyright © Truthout. May not be reprinted without permission.

C.J. Polychroniou is a political economist/political scientist who has taught and worked in universities and research centers in Europe and the United States. His main research interests are in European economic integration, globalization, the political economy of the United States and the deconstruction of neoliberalism’s politico-economic project. He is a regular contributor to Truthout as well as a member of Truthout’s Public Intellectual Project. He has published several books and his articles have appeared in a variety of journals, magazines, newspapers and popular news websites. Many of his publications have been translated into several foreign languages, including Croatian, French, Greek, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish and Turkish. He is the author of Optimism Over Despair: Noam Chomsky On Capitalism, Empire, and Social Change, an anthology of interviews with Chomsky originally published at Truthoutand collected by Haymarket Books.

Alias Bob Dylan – Heimwee naar de verbeelding

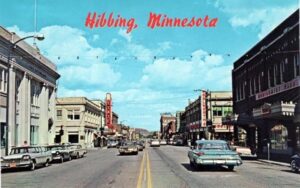

Het moet 1964 geweest zijn toen de mythe ontstond dat de jonge Robert Zimmerman, afkomstig uit Hibbing, Minnesota, als een soort eerbetoon aan de Ierse dichter Dylan Thomas, zijn naam had veranderd in Bob Dylan. Tot ver in de jaren zeventig dook het verhaal in allerlei artikelen en beschouwingen over Dylan op. In 1965 had Dylan al tegen een journalist van The Chicago Daily News gezegd: ‘I took the name Dylan because I have an uncle named Dillion. I changed the spelling but only because it looked better. I’ve read some of Dylan Thomas’s stuff, and it’s not the same as mine’.

Het moet 1964 geweest zijn toen de mythe ontstond dat de jonge Robert Zimmerman, afkomstig uit Hibbing, Minnesota, als een soort eerbetoon aan de Ierse dichter Dylan Thomas, zijn naam had veranderd in Bob Dylan. Tot ver in de jaren zeventig dook het verhaal in allerlei artikelen en beschouwingen over Dylan op. In 1965 had Dylan al tegen een journalist van The Chicago Daily News gezegd: ‘I took the name Dylan because I have an uncle named Dillion. I changed the spelling but only because it looked better. I’ve read some of Dylan Thomas’s stuff, and it’s not the same as mine’.

Robert Shelton, journalist bij The New York Times, begon in 1966 aan een biografie over Dylan (No Direction Home. Het boek zou pas in 1986 verschijnen). Verschillende malen liet Dylan aan Shelton weten: ‘Straigthen out in your book that I did not take my name from Dylan Thomas’.

Dylan was Shelton sowieso dankbaar, want in september 1961 had Shelton in de New York Times de eerste – lovende – recensie over een optreden van Dylan geschreven. Dylan was op dat moment slechts bekend bij een kleine kring van bezoekers van folkcafé’s in Greenwich Village. De recensie bracht hem onder de aandacht van Columbia Records en van producer John Hammond en bezorgde hem een platencontract.

Interview

Interview

Inmiddels weten we dat veel van wat Dylan in interviews verklaarde met een flinke korrel zout genomen moet worden. Met biografische gegevens is hij altijd uiterst karig geweest en verschillende verhalen die hij over zijn jeugd en puberjaren vertelde, bleken achteraf geheel verzonnen. Legendarisch is een van zijn eerste radio-interviews. Nog voor de release van zijn eerste plaat interviewde presentatrice Cynthia Gooding hem in maart 1962 een uur lang voor WBAI-FM Radio, New York. Onduidelijk is of het programma ooit is uitgezonden maar het is gelukkig wel bewaard gebleven. [1] Zo vertelt hij Gooding dat hij op jeugdige leeftijd wegliep van huis en enkele jaren met een circus door de Verenigde Staten was getrokken. In New Orleans zou hij op 12-jarige leeftijd kennis gemaakt hebben met oude bluesmuzikanten die hem het mondharmonicaspelen hadden geleerd. Niets van waar: het bleken gefingeerde biografische verhalen. Soortgelijke ‘herinneringen’ zou hij in zijn beginjaren nog wel vaker verkondigen.

Artiestennaam

Artiestennaam

Maar als de naam Dylan geen betrekking had op Dylan Thomas, op wie dan wel? Dylan vertelde vrienden dat de naam gebaseerd was op Dillon, de achternaam van zijn moeder. Maar dat was niet waar zo bleek later, de moeder van Robert Zimmerman heette Beatrice Stone.

Over de oom Dillion heeft Dylan nooit meer gesproken.

In zijn highschool-jaren trad Robert Zimmerman zo nu en dan op schoolfeesten en county fairs op samen met jeugdvriend John Bucklen, overigens niet altijd tot genoegen van het publiek.

Voor iemand die het ver wilde schoppen in de muziek, en dat wilde de jonge Robert, was Zimmerman wellicht geen goeie artiestennaam. In 1958 zei hij tegen Bucklen: ‘I know what I’m going to call myself. I’ve got this great name – Bob Dillon.’

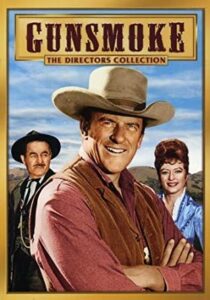

Misschien is de achtergrond van de naam Dylan dan ook veel minder prozaïsch dan vaak gesuggereerd. Robert Zimmerman was in zijn jeugd een grote fan van de westerntelevisieserie Gunsmoke, waarin de rechtvaardige Marshal Matt Dillon (acteur James Arness) in het westernstadje Dodge City de orde weet te handhaven. Mogelijk is de Dillon/Dylan-naamgeving niet meer dan de jeugddroom een held te willen zijn, of op zijn minst zich te willen onderscheiden van de rest.

Westernseries

Westernseries

Hibbing, een plaatsje met zo’n tienduizend inwoners was tot bloei gekomen dankzij de omringende ijzerertsmijnen, maar in de jaren vijftig was de bloeitijd van het stadje al lang voorbij. Voor de opgroeiende jeugd was er niet veel te beleven. Er was een bioscoop, meer vermaak was er niet. In 1952 kon het gezin Zimmerman zich als eerste in Hibbing een televisie veroorloven. De jonge Bob bracht met zijn vrienden urenlang voor het toestel door.

Hij keek naar musicals en variety shows, maar zijn voorkeur ging uit naar westernseries als Wyatt Earrp, Kit Carson, Davey Crockett, maar vooral de serie Gunsmoke was zijn favoriet.

Vertraagd geweld

Van de serie Gunsmoke werden tussen 1955 en 1975 635 afleveringen gemaakt. Met kijkersogen van nu, ruim zestig jaar later, oogt de serie als uitermate braaf. In de volgens een vast stramien opgebouwde afleveringen werden de problemen in het keurige, burgerlijke plaatsje Dodge City op een beschaafde manier door Marshal Dillon opgelost. Daarbij vielen natuurlijk wel schoten en doden vielen er ook, maar zichtbaar bloed vloeide er nooit.

Voor veel acteurs en regisseurs was de serie het startpunt van hun carrière. Bijvoorbeeld voor Dennis Weaver, die in de jaren zeventig de succesvolle serie McCloud maakte, en voor regisseur Sam Peckinpah. Peckinpah had al naam gemaakt als scenarioschrijver van tientallen afleveringen van de populaire westernserie Broken Arrow, maar voor Gunsmoke mocht hij het als regisseur proberen. Tussen 1955 en 1958 regisseerde hij elf afleveringen. Daarnaast maakte hij afleveringen van de westernseries The Rifleman en The Westerner. In de jaren zestig regisseerde hij de westerns Wichita, Major Dundee en Villa Rides. Bekendheid kreeg Peckinpah in 1969 als regisseur van de snoeiharde western The Wild Bunch, waarin hij alle film- en westernwetten overtrad door geweld vooral zo bloedig mogelijk in beeld te brengen, het liefst vertraagd vertoond en vanuit verschillende camerastandpunten gefilmd. In de jaren zeventig zou vertraagd geweld Peckinpahs handelsmerk blijken te zijn. Hij maakte onder meer films als Straw Dogs, The Getaway, Bring me the Head of Alfredo Garcia en Cross of Iron. In 1973 maakte hij zijn laatste western, Pat Garret and Billy the Kid, met in de hoofdrollen James Coburn en Kris Kristofferson.

Voor veel acteurs en regisseurs was de serie het startpunt van hun carrière. Bijvoorbeeld voor Dennis Weaver, die in de jaren zeventig de succesvolle serie McCloud maakte, en voor regisseur Sam Peckinpah. Peckinpah had al naam gemaakt als scenarioschrijver van tientallen afleveringen van de populaire westernserie Broken Arrow, maar voor Gunsmoke mocht hij het als regisseur proberen. Tussen 1955 en 1958 regisseerde hij elf afleveringen. Daarnaast maakte hij afleveringen van de westernseries The Rifleman en The Westerner. In de jaren zestig regisseerde hij de westerns Wichita, Major Dundee en Villa Rides. Bekendheid kreeg Peckinpah in 1969 als regisseur van de snoeiharde western The Wild Bunch, waarin hij alle film- en westernwetten overtrad door geweld vooral zo bloedig mogelijk in beeld te brengen, het liefst vertraagd vertoond en vanuit verschillende camerastandpunten gefilmd. In de jaren zeventig zou vertraagd geweld Peckinpahs handelsmerk blijken te zijn. Hij maakte onder meer films als Straw Dogs, The Getaway, Bring me the Head of Alfredo Garcia en Cross of Iron. In 1973 maakte hij zijn laatste western, Pat Garret and Billy the Kid, met in de hoofdrollen James Coburn en Kris Kristofferson.

Dylan, bevriend met Kristofferson, toonde interesse in een rol in de film en kreeg via de producer het script toegespeeld. Hij ging naar een voorstelling van The Wild Bunch en raakte zozeer enthousiast over de stijl van Peckinpah dat hij meteen erna de song Billy the Kid schreef. [2] Peckinpah was onder de indruk van het nummer en draaide het vrijwel continu.

Dylan mocht de soundtrack voor de film schrijven en kreeg zowaar een rolletje toebedeeld, als Alias, een hulpje van Billy the Kid.

Pseudoniemen

Alias. Hoe toepasselijk kan een naam zijn, want in de loop der jaren bediende Dylan zich van vele pseudoniemen. Hij noemde zich Elston Gunn toen hij in 1959 drie dagen lang deel uitmaakte van de begeleidingsgroep van vroege rocker Bobby Vee, totdat hij uit de band werd gezet omdat hij teveel aandacht van het publiek opeiste. Als Tedham Porterhouse speelde hij in 1964 harmonica op de elpee Ramblin’ Jack van Ramblin’ Jack Elliot. In datzelfde jaar speelde hij als Blind Boy Grunt enkele songs op een plaat van het folktijdschrift Broadside.

Op de elpee The Blues Project. A Compendium of the Very Best on the Urban Blues Scene uit 1965, met o.a. Geoff Mudaur, Dave van Ronk en Eric von Schmidt, speelt hij piano als Bob Landy.[3] ‘To musicians, his piano playing is almost legend’, staat vermeld in de hoestekst. In 1972 verscheen hij als Robert Milkwood Thomas (!) op de plaat Somebody Else’s Troubles van Steve Goodman. Als Lucky Wilbury maakte hij deel uit van The Traveling Wilburys, de groep met George Harrison, Jeff Lynne, Roy Orbison en Tom Petty (1988), op hun tweede plaat heette hij Boo Wilbury (1990). Onder de naam Sergei Petrov schreef hij mee aan het scenario voor de film Masked and Anonymous (2003), waarin Dylan de rocklegende Jack Fate speelt. De afgelopen decennia produceerde hij zijn eigen platen onder de naam Jack Frost.

Op de elpee The Blues Project. A Compendium of the Very Best on the Urban Blues Scene uit 1965, met o.a. Geoff Mudaur, Dave van Ronk en Eric von Schmidt, speelt hij piano als Bob Landy.[3] ‘To musicians, his piano playing is almost legend’, staat vermeld in de hoestekst. In 1972 verscheen hij als Robert Milkwood Thomas (!) op de plaat Somebody Else’s Troubles van Steve Goodman. Als Lucky Wilbury maakte hij deel uit van The Traveling Wilburys, de groep met George Harrison, Jeff Lynne, Roy Orbison en Tom Petty (1988), op hun tweede plaat heette hij Boo Wilbury (1990). Onder de naam Sergei Petrov schreef hij mee aan het scenario voor de film Masked and Anonymous (2003), waarin Dylan de rocklegende Jack Fate speelt. De afgelopen decennia produceerde hij zijn eigen platen onder de naam Jack Frost.

Speelfilms

Speelfilms

Bob Dylan is een filmliefhebber, dat is bekend. In 1956, na het zien van de film Giant met James Dean, wilde hij niets liever dan de nieuwe James Dean worden. Zijn rebellie uitte hij dan wel niet als filmster maar als folk- en rockartiest, zijn liefde voor film en met name voor western is in zijn songs terug te vinden.

Michael Gray, auteur van de indrukwekkende studie Song & Dance Man III. The Art of Bob Dylan (2000), was de eerste die merkte dat sommige passages in Dylansongs een opvallende overeenkomst vertoonden met dialogen of zinsneden uit speelfilms. Nauwgezette studie bracht aan het licht dat Dylan uit maar liefst 61 speelfilms citaten in songs heeft gebruikt, of verwijst naar filmtitels.[4] Negen daarvan zijn westerns, negentien titels – waarvan zes films met Humphrey Bogart – stammen uit de jaren veertig en vijftig, de periode van de film noir, bijvoorbeeld Casablana, To Have and Have Not, Shoot the Piano Player en Rear Window.

Enkele voorbeelden:

The Big Sleep (1946)

Bogart: ‘What’s wrong with you?’

Bacall: ‘Nothing you can’t fix’

Dylan in Seeing the Real You at Last:

‘At one time there was nothing wrong with me,

That you could not fix’

The Oklahoma Kid (1939)

Cagney: ‘You want to talk with me’

Bogart: ‘Go ahead and talk’

Dylan in Tight Connection on my Heart:

‘You want to talk to me

Go ahead and talk’

The Lusty Men (1952)

Mitchum: ‘Broken bottles, broken bones, everything is broken’

Dylan in Everything is Broken:

‘Broken bottles, broken plates,

Broken switches, broken gates

…

Everything is broken’

In Bronco Billy (1980), een film over een rodeocowboy (eigenlijk een moderne western) zegt Clint Eastwood: ‘I’m looking for a woman who can ride like Annie Oakley and shoot like Belle Starr’.[5] In de song Seeing the Real You at Last (1985) zingt Dylan:

In Bronco Billy (1980), een film over een rodeocowboy (eigenlijk een moderne western) zegt Clint Eastwood: ‘I’m looking for a woman who can ride like Annie Oakley and shoot like Belle Starr’.[5] In de song Seeing the Real You at Last (1985) zingt Dylan:

‘When I met you baby

You didn’t show no visible scars.

You could ride like Annie Oakley

You could shoot like Belle Starr’

Het zou zo een citaat uit een film met Humphrey Bogart kunnen zijn.

Amerika

Meer nog dan Dylans soundtrack voor Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid ademt zijn achtste elpee John Wesley Harding de sfeer van een westernfilm uit. Titel en titelsong verwijzen niet alleen naar outlaw en gunfighter John Wesley Hardin (1853-1895), een song als The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest roept beelden op van een westernstadje waar oplichters, mysterieuze godsdienstpredikers en zwervende outlaws de dienst uitmaken. Beelden zoals we die wel kennen uit klassieke westernfilms. Op de plaat heerst een geheimzinnige, soms onheilspellende sfeer, waarbij een Bijbels noodlot ieder moment lijkt te kunnen toeslaan. (De plaat bevat zo’n zestig verwijzingen naar de Bijbel, maar dat is een ander verhaal.)

De elpee dateert uit dezelfde periode (1968) waarin de beroemde Basement Tapes werden opgenomen. Dylan en The Band namen ruim honderd songs op in de kelder van het huis Big Pink in Woodstock. De in 1975 uitgebrachte plaat The Basement Tapes was hiervan slechts een magere selectie. De in 2014 uitgebrachte box The Basement Tapes Raw, The Bootleg Series Vol. 11 bood bijna alle opgenomen songs. De opnames lijken die van John Wesley Harding in een breder kader te plaatsen. Oude folk- en bluessongs en nieuwe songs van Dylan schetsen het beeld van een verdwenen Amerika, een negentiende eeuws gebied bevolkt door outlaws, hobo’s, landarbeiders, slaven en immigranten. Ballades uit de Appalachian Mountains, countrysongs, murderballads, kinderliedjes en gospelsongs vertellen de geschiedenis van dat verdwenen Amerika. The Basement Tapes weerspiegelen dat verleden en maken de luisteraar deelgenoot van die geschiedenis, alsof het filmbeelden zijn van een nog te maken epos over een mythisch, vrijwel vergeten land. Een land dat misschien alleen in de verbeelding bestaat. In die verbeelding kan Marshall Matt Dillon de orde handhaven.

Noten

Noten

[1] Het interview met Dylan is te beluisteren op https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=483m8ADfG48

[2] Bob Dylan: Billy the Kid (audio) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZEi83f_CEqM

[3] Geoff Mudaur, Downtown Blues, on piano Bob Landy (audio) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BCSsCK86ldc

[4] Movie quotes in Bob Dylan songs http://www.geocities.ws/linwood/cinema/Dylan-Film/

[5] Annie Oakley (1860-1926), legendarische Amerikaanse scherpschutster. Belle Starr (1848- 1889), outlaw, maakte deel uit van de bende van Jesse en Frank James.

De oudste bewegende beelden van Dylan (ca.1961)

Noam Chomsky: Biden’s Foreign Policy Is Largely Indistinguishable From Trump’s

President Joe Biden’s domestic policies, especially on the economic front, are quite encouraging, offering plenty of hope for a better future. The same, however, cannot be said about the administration’s foreign policy agenda, as Noam Chomsky’s penetrating insights and astute analysis reveal in this exclusive interview for Truthout. Chomsky is a world-famous public intellectual, Institute Professor Emeritus at MIT and Laureate Professor of Linguistics at the University of Arizona.

C.J. Polychroniou: Noam, two months after being in the White House, Biden’s foreign policy agenda is beginning to take shape. What are the signs so far of how the Biden administration intends to address the challenges to U.S. hegemony posed by its primary geopolitical rivals, namely Russia and China?

Noam Chomsky: The challenge to U.S. hegemony posed by Russia and particularly China has been a major theme of foreign policy discourse for some time, with persistent agreement on the severity of the threat.

The matter is plainly complex. It’s a good rule of thumb to cast a skeptical eye when there is general agreement on some complex issue. This is no exception.

What we generally find, I think, is that Russia and China sometimes deter U.S. actions to enforce its global hegemony in regions on their periphery that are of particular concern to them. One can ask whether they are justified in seeking to limit overwhelming U.S. power in this way, but that is a long distance from the way the challenge is commonly understood: as an effort to displace the U.S. global role in sustaining a liberal rule-based international order by new centers of hegemonic power.

Do Russia and China actually challenge U.S. hegemony in the ways commonly understood?

Russia is not a major actor in the world scene, apart from the military force that is a (very dangerous) residue of its earlier status as a second superpower. It does not begin to compare with the U.S. in outreach and influence.

China has undergone spectacular economic growth, but it is still far from approaching U.S. power in just about any dimension. It remains a relatively poor country, ranked 85th in the UN Human Development Index, between Brazil and Ecuador. The U.S., while not ranked near the top because of its poor social welfare record, is far above China. In military strength and global outreach (bases, forces in active combat), there is no comparison. U.S.-based multinationals have about half of world wealth and are first (sometimes second) in just about every category. China is far behind. China also faces serious internal problems (ecological, demographic, political). The U.S., in contrast, has internal and security advantages unmatched anywhere.

Take sanctions, a major instrument of world power for one country on Earth: the U.S. They are, furthermore, third-party sanctions. Disobey them, and you’re out of luck. You can be tossed out of the world financial system, or worse. It’s pretty much the same wherever we look.

If we look at history, we find regular echoes of Sen. Arthur Vandenberg’s 1947 advice to the president that he should “scare hell out of the American people” if he wanted to whip them up to a frenzy of fear over the Russian threat to take over the world. It would be necessary to be “clearer than truth,” as explained by Dean Acheson, one of the creators of the postwar order. He was referring to NSC-68 of 1950, a founding document of the Cold War, declassified decades later. Its rhetoric continues to resound in one or another form, again today about China.

NSC-68 called for a huge military build-up and imposition of discipline on our dangerously free society so that we can defend ourselves from the “slave state” with its “implacable purpose… to eliminate the challenge of freedom” everywhere, establishing “total power over all men [and] absolute authority over the rest of the world.” And so on, in an impressive flow.

China does confront U.S. power — in the South China Sea, not the Atlantic or Pacific. There is an economic challenge as well. In some areas, China is a world leader, notably renewable energy, where it is far ahead of other countries in both scale and quality. It is also the world’s manufacturing base, though profits go mostly elsewhere, to managers like Taiwan’s Foxconn or investors in Apple, which is increasingly reliant on intellectual property rights — the exorbitant patent rights that are a core part of the highly protectionist “free trade” agreements.

China’s global influence is surely expanding in investment, commerce, takeover of facilities (such as management of Israel’s major port). That influence is likely to expand if it moves forward with provision of vaccines virtually at cost in comparison with the West’s hoarding of vaccines and its impeding of distribution of a “People’s Vaccine” so as to protect corporate patents and profits. China is also advancing substantially in high technology, much to the consternation of the U.S., which is seeking to impede its development.

It is rather odd to regard all of this as a challenge to U.S. hegemony.

Is Neoliberalism Dying? A Structuralist Approach To Predatory Global Capitalism And The Challenge of Reform*

C.J. Polychroniou

Forty years of neoliberal rule have produced devastating effects on lower and working-class people and on the social fabric throughout the world: wages have stagnated, labor rights have been trampled, and economic inequalities have exploded. Neoliberalism has also proven detrimental to democracy as many forms of collective decision-making and even faith and trust in the ability of government to solve problems have been severely eroded by the marketization project. Citizens have been encouraged to think and act like consumers and powerful private interests have made a mockery of the idea of a common good. Moreover, trends of ongoing income and wealth inequality combined with job insecurity and the hijacking of the state by the economic elites has led to the eruption of popular anger, leading to the rise of a new generation of authoritarian rulers and to a concomitant attack on the traditional democratic order, along with an explosion of xenophobic rage and racism.

Nonetheless, neoliberalism has remained the hegemonic paradigm in the workings of contemporary capitalism and the operating framework of the global economy, even though this particular form of economic governance is prone to systemic crises and in spite of challenges and sporadic forms of resistance from below.

At least until now, that is. For the eruption of the pandemic appears to have discredited market fundamentalism and state interventionism has returned with vengeance throughout the West. We have seen massive monetary and fiscal packages introduced both in Europe and the United States in order to provide relief for unemployed workers and struggling businesses in ways that have not been seen in many decades. During the global financial crisis of 2008, the state bailed out the financial sector and turned a blind eye towards homeowners and the millions of people suffering from the consequences of “predatory capitalism” that neoliberalism gave rise to from the mid-1970s and continued to fuel throughout the next four decades. However, during the era of the pandemic, the state has come to some degree to the rescue of the entire economy, although still not as aggressively as economic thinking associated with the name and work of John Maynard Keynes would surely recommend for a crisis as severe as the one thrusted upon the world by the eruption of the Covid pandemic, which has created a classic capitalist crisis of accumulation.

Be that as it may, the question popping up suddenly (once again, we might add, since the same question popped up after the financial crisis of 2008) is whether the return of “Big Government” during the pandemic is signaling the end of neoliberalism.

My view on this matter is that it is too early to tell, and, more importantly, that neoliberalism is not going to wither away without an increased role of participatory democracy and the emergence of political vehicles (political parties and social movements) envisioning and fighting for an alternative social order. Neoliberalism is not merely an ideology or even a specific policy at this point, but an institutional component, a substructure, of the very capitalist system that has been built in the age of globalization, and thus the measures taken today to address the economic effects of the pandemic may be quite temporary and the world could easily return to “business as usual” once the pandemic has been brought under control.

Let me elaborate

Any effort to fully understand the nature of contemporary capitalism should begin with the recognition that the whole is indeed greater than the sum of its parts. It is also pertinent that we recognize the importance of structural causality in making sense of contemporary capitalist developments while avoiding methodological reductionism. As such, we need to look at the overall structure of the system; that is, we need to comprehend the different constitutive parts of the system that keep it together and running in ways which are harmful to the interests of the great majority of the population, dangerous to democracy and public values, and detrimental to the environment and earth’s ecosystem. Focusing on one element of the system while ignoring other things (perhaps because we think that they constitute incidental outcomes or processes of secondary nature) may limit our understanding by creating a flawed perspective about the dynamics and the contradictions of contemporary capitalism and thereby undermine our ability to propose sound and realistic solutions.

Now, we know what capitalism is, and how it basically works. It is a specific, historically determined mode of production, a ruthless economic system representing the most advanced form of commodity production. It is not an economic system designed to serve the needs of society as such, because the extraction of profit is the “logic” that drives capitalist commodity production. Not only that, but when left to operate without regulations, capitalism can wreak havoc on societies. Exploitation and inequality represent structural necessities of the system itself, and capital itself is nothing other than value that generates surplus value.

Moreover, capital accumulation is an anarchic and contradictory process, and with a constant need to expand, all of which result all too frequently in systemic crises that threaten to destroy capitalism itself and which, subsequently, mandate the intervention of the state in order to save the system from collapse. In the age of the financialization of capital, systemic crises have become far more frequent, and with greater severity, and government bailouts have emerged as the essential tool through which the system avoids a catastrophic collapse.

Capitalist expansion has taken place over the course of the past five centuries via different venues, ranging from plunder and exploitation, through trade, to investment in industry and the financialization of assets. However, the state has been the driving agency behind the spread and consolidation of capitalism from the very start. And it is no less the case than with the architecture of contemporary capitalism.

The landscape of contemporary capitalism has been structured around three interrelated elements: financialization, neoliberalism and globalization. All three of these components constitute part of a coherent whole which has given rise to an entity that can be briefly described as “predatory global capitalism.”

As such, contemporary capitalism is characterized by a political economy which revolves around finance capital, is based on a savage form of free market fundamentalism and thrives on a wave of globalizing processes and global financial networks that have produced global economic oligarchies with the capacity to influence the shaping of policymaking across nations. Indeed, today’s brand of capitalism is particularly anti-democratic and simply incapable of functioning in a way conducive to maintaining sustainable and balanced growth. By waging vicious class warfare, the economic elite and their allies have managed in the contemporary era to roll back progress on the economic and social fronts by resurrecting the predatory, “free-market” capitalism that immiserated millions in the early 20th century while a handful of obscenely wealthy individuals controlled the bulk of the wealth.

The capitalist order we have in place today has its roots in the structural changes that took place in the accumulation process back in the mid-to-late 1970s. The 1970s was a decade of economic slowdown and inflationary pressures in the advanced capitalist world. The crisis, brought about by new technological innovations, declining rates of profit and the dissolution of the social structures of accumulation that had emerged after World War II, led to sluggish growth rates, high inflation and even higher rates of unemployment, bringing about a phenomenon that came to be known as “stagflation.”

From a policy point of view, “stagflation” signaled the end of an era in which there was a trade-off between inflation and unemployment (shown by the Phillips curve) and, by extension, the end of the dominance of the Keynesian school of thought.

Chomsky: Biden’s Early Agenda Gives Hope, But Activist Pressure Must Not Cease

Joe Biden’s first months in office have comprised a flurry of actions on the domestic front, including a historic stimulus bill. In this exclusive interview, the celebrated public intellectual Noam Chomsky shares his views on some key policies embraced by the Biden administration. Chomsky is Institute Professor Emeritus at MIT and Laureate Professor of Linguistics at the University of Arizona. His latest books are Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (co-authored with Robert Pollin and C. J. Polychroniou; Verso, 2020), Chomsky for Activists (Routledge, 2020) and Consequences of Capitalism: Manufacturing Discontent and Resistance(Haymarket Books, 2020).

C.J. Polychroniou: President Joe Biden has been in office for approximately two months now, in the course of which he has signed scores of executive orders meant to reverse the policies of Donald Trump. But he has also managed to pass a huge and ambitious stimulus bill unlike anything seen during peacetime. What’s your assessment of Biden’s actions so far to deal with the most pressing issues facing U.S. society: namely, the coronavirus pandemic and the pain caused to millions of Americans on account of the pandemic?

Noam Chomsky: Better than I’d anticipated. Considerably so.

The stimulus bill has its flaws, but considering the circumstances, it’s an impressive achievement. The circumstances are a highly disciplined opposition party dedicated to the principle announced years ago by its maximal leader, Mitch McConnell: If we are not in power, we must render the country ungovernable and block government legislative efforts, however beneficial they might be. Then the consequences can be blamed on the party in power, and we can take over. It worked well for Republicans in 2009 — with plenty of help from Obama. By 2010, the Democrats lost Congress, and the way was cleared to the 2016 debacle.

There’s every reason to suppose that the strategy will be renewed — this time under more complex circumstances. The voting base in the hands of Trump, who shares the objective but differs from McConnell on who will pick up the pieces: McConnell and the donor class, or Trump and the voting base he mobilized, almost half of whom worship him as the messenger God sent to save the country from … we can fill in our favorite fantasies, but should not overlook the fact that what may sound [ridiculous] has roots in the lives of the victims of the neoliberal globalization of the past 40 years — extended by Trump, apart from some rhetorical flourishes.

In those circumstances, passing a stimulus bill was a major accomplishment. Republicans who favor it, and know that their constituents do, nevertheless voted against it, in lockstep obedience to what the Central Committee determines. Some Democrats insisted on watering it down. But what finally passed has valuable elements, which could be a basis for moving on.

There are huge gaps. The bill surely should have contained an increase in the miserable minimum wage, an utter scandal. But that would have been very difficult in the face of total Republican opposition, along with a few Democrats. And there are other crucial features that are missing. Nevertheless, if the short-term measures on child poverty, income support, medical insurance and other basic needs can be extended, it would be a substantial step toward fulfilling the promise envisioned by such careful observers as Roosevelt Institute President Felicia Wong, who reflected that, “As I see it, both the scale and the direction of the American Rescue Plan break the neoliberal, deficits-and-inflation-come-first mold that has hollowed out our economy for a generation.” We haven’t seen anything that could elicit such hopes for a long time.

There is also hope in appointments on economic issues. Who would have imagined that a regular contributor to radical economics journals would be appointed to the Council of Economic Advisers (Heather Boushey), joined by the senior economic adviser of the labor-oriented Economic Policy Institute, (Jared Bernstein)?

Biden’s strong support for Amazon workers, and unions generally, is a welcome shift. Nothing like it has been heard from the chambers of power in many years. In a sharp reversal of Trump legislation, the tax changes raise incomes mostly for the poor, not the rich. Economic Policy Institute President Thea Lee summarizes the package by saying that it “will provide crucial support to millions of working families; dramatically reduce the race, gender, and income inequalities that were exacerbated by the crisis; and create the conditions for a truly robust recovery once the virus is under control and people are able to resume normal economic activity.” Optimistic, but within reach.

House Democrats have passed other important legislation. H.R. 1 protects voting rights, a critical matter now, with Republicans working overtime to try to block the votes of [people of color] and the poor, recognizing that this is the only way a minority party dedicated to wealth and corporate power can remain viable.

On the labor front, the House passed the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act, “a critical step toward restoring workers’ right to organize and bargain collectively,” the Economic Policy Institute reports, a fundamental right that “has been eroded for decades as employers exploited weaknesses in the current law.” It’ll probably be killed by the Senate. Even apart from party loyalty, there is little sympathy for working people in Republican ranks.

But even so, it’s a basis for organizing and education. It can be a step toward revitalizing the labor movement, a prime target of the neoliberal project since Reagan and Thatcher, who understood well that working people must be deprived of means to defend themselves from the assault.

Decline of union membership is by now recognized, even in the mainstream, to be a major factor in rising inequality — a phrase that translates to “robbery of the general public by a tiny fraction of super-rich.” The Economic Policy Institute has reviewed the facts regularly, most recently in a chart that graphically demonstrates the remarkable correlation between rising/falling union membership and falling/rising inequality.

More generally, there is a good opportunity to overcome the baleful legacy of Trump’s bitterly anti-labor Labor Department, headed by corporate lawyer Eugene Scalia, who used his term in office to eviscerate worker rights, notoriously during the pandemic. Scalia was perfectly chosen for the transformation of the Republicans to a “working-class party,” as hailed by Marco Rubio and Josh Hawley in a triumph of propaganda, or maybe sheer chutzpah.

Michael Regan’s appointment as Environmental Protection Agency administrator should replace corporate greed by science and human welfare in this essential agency, a move toward human decency that in this case is a prerequisite for survival.

It’s easy to find serious omissions and deficiencies in Biden’s programs on the domestic front, but there are signs of hope for emerging from the Trump nightmare and moving on to what really should, what really must be done. The hopes are, however, conditional. The temporary measures of the stimulus on child poverty and many other issues must be made permanent, and improved. Crucially, activist pressure must not cease. The masters of the universe pursue their class war relentlessly, and can only be countered by an aroused public opposition that is no less dedicated to the common good.

What do you think of Biden’s refusal to cancel $50,000 in student loans?

A bad decision. What the realistic options were, I don’t frankly know. Higher education at a high level should be recognized to be a basic right, freely available, as it is elsewhere: in our Mexican neighbor, in rich developed countries like Germany, France, the Nordic countries, and a great many others, with at most nominal fees. As it substantially was in the U.S. when it was a much poorer country than it is today. The postwar GI Bill of Rights provided free education for great numbers of white males who would never have gone to college otherwise. There is no reason why young people of any race should be denied the privilege today.

In light of the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol, Biden has vowed to fight domestic terrorism by passing a new law “that respects free speech and civil liberties.” Does the U.S. need a new domestic terrorism agenda?

A prior question is whether we should retain the current domestic terrorism agenda. There are strong reasons to question that. And any expansion should be a matter of serious concern. That aside, white supremacist violence is no laughing matter. Through the Trump years, the FBI and other monitors report steadily increasing white supremacist terror, by now covering almost all recorded terror. Armed militias are rampant — Trump’s “tough guys” as he’s admiringly called them. The problems can’t be overlooked, but have to be handled with great caution and a close eye on the temptations for abuse.

Biden has proposed a plan to strengthen the middle class by encouraging unionization and collective bargaining, and his recent affirmation of the rights of workers to unionize, which was widely interpreted as support for Amazon workers’ rights to organize in Alabama, has spread considerable enthusiasm among progressives. Indeed, Biden’s support for unions is in pace with the highly favorable ratings that unions have been receiving in the last couple of years. What’s behind the support for unions in the present era?

One reason is objective reality. The sharp rise in inequality is a growing curse, with extremely harmful effects across the society. As mentioned earlier, it closely tracks decline of unions, for reasons that are well understood. Historically, labor unions have been in the forefront of struggles for justice and rights. They also pioneered the environmental movement, as we’ve discussed before. Workers’ organizations are changing in character with the growth of service and knowledge-based economies. They have shared interests, and foster the values of solidarity and mutual aid on which the hope for a decent future rest. Many unions retain the world “international” in their names. It should not just be a symbol or a dream. The dire challenges we face have no borders. Global heating, pandemics, disarmament will be dealt with internationally, if at all. The same is true of labor rights and human rights more generally. At every level, associations of working people should once again be prominent, if not leading the way, toward a better world.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Copyright: https://truthout.org/

C.J. Polychroniou is a political economist/political scientist who has taught and worked in universities and research centers in Europe and the United States. His main research interests are in European economic integration, globalization, the political economy of the United States and the deconstruction of neoliberalism’s politico-economic project. He is a regular contributor to Truthout as well as a member of Truthout’s Public Intellectual Project. He has published several books and his articles have appeared in a variety of journals, magazines, newspapers and popular news websites. Many of his publications have been translated into several foreign languages, including Croatian, French, Greek, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish and Turkish. He is the author of Optimism Over Despair: Noam Chomsky On Capitalism, Empire, and Social Change, an anthology of interviews with Chomsky originally published at Truthoutand collected by Haymarket Books.

Phasing Out Fossil Fuels Is Possible. These State-Level Plans Show How

When it comes to climate change, state governments across the United States have been way ahead of the federal government in providing leadership toward reducing carbon pollution and building a clean energy economy. For example, when Trump announced in 2017 his intention to withdraw the U.S. from the Paris Agreement, the governors of California, Washington and New York pledged to support the international agreement, and by 2019, more than 20 other states ended up joining this alliance to combat global warming.

Robert Pollin, distinguished professor of Economics and co-director of the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, has been a driving force behind several U.S. states’ efforts to curb carbon emissions and make a transition to a green economy. In this exclusive Truthout interview, Pollin talks about how states can take crucial, proactive steps to build a clean energy future.

C.J. Polychroniou: Bob, you are the lead author of commissioned studies, produced with some of your colleagues at the Political Economy Research Institute of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, to fight climate change for scores of U.S. states, including Pennsylvania, Ohio, West Virginia, Maine, Colorado, Washington, New York and California. The purpose of those studies is to show the way for states to attain critical reductions in carbon emissions while also embarking on a path of economy recovery and a just transition toward an environmentally sustainable environment. In general terms, how is this to be done, and is there a common strategy that all states can follow?

Robert Pollin: The basic framework that we have developed is the same for all states. For all states, we develop a path through which the state can reduce its carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions by roughly half as of 2030 and to transform into a zero emissions economy by 2050. These are the emissions reduction targets set out by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (the IPCC) that are meant to apply to the entire global economy. The IPCC — which is a UN agency that serves as a clearinghouse for climate change research — has concluded that these CO2 emissions reduction targets have to be met in order for we, the human race, to have a reasonable chance to stabilize the global average temperature at no more than 1.5 degrees Celsius above the preindustrial level, [the level of] about the year 1800.

The IPCC has concluded that stabilizing the global average temperature at no more than 1.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels provides the only realistic chance for avoiding the most severe destructive impacts of climate change in terms of heat extremes, heavy precipitation, droughts, floods, sea level rise, biodiversity losses, and the corresponding impacts on health, livelihoods, food security, water supply and human security. Given that these emissions reduction targets must be met on a global scale, it follows that they also must be met in every state of the United States, with no exceptions, just like they must be met in every other country or region of the world with no exceptions.

By far the most important source of CO2 emissions entering the atmosphere is fossil fuel consumption — i.e., burning oil, coal and natural gas to produce energy. As such, the program we develop in all of the U.S. states centers on the state’s economy phasing out its entire fossil fuel industry — i.e., anything to do with producing or consuming oil, coal or natural gas — at a rate that will enable the state to hit the two IPCC emissions reduction targets: the 50 percent reduction by 2030 and zero emissions within the state by 2050.

Of course, meeting these emissions reduction targets raises a massive question right away: How can you phase out fossil fuels and still enable people to heat, light and cool their homes and workplaces; for cars, buses, trains and planes to keep running; and for industrial machinery of all types to keep operating?

It turns out that, in its basics, the answer is simple and achievable, in all the states we have studied (and everywhere else for that matter): to build a whole new clean energy infrastructure that will supplant the existing fossil fuel dominant infrastructure in each state. So the next major feature of our approach is to develop investment programs to dramatically raise energy efficiency standards in buildings, transportation systems and industrial equipment, and equally dramatically expand the supply of clean renewable energy sources, i.e. primarily solar and wind energy, but also geothermal, small-scale hydro, as well as low-emissions bioenergy.

For all but one of the states we have studied, we estimate that the amount of clean energy investments that are needed amounts to between 1-3 percent of all state economic activity, i.e. the state’s GDP (Gross Domestic Product). That can be a lot of money — like $6.6 billion in Washington State (1.2 percent of projected average GDP between 2021-2030), $22.6 billion in Pennsylvania (2.5 percent of projected average GDP between 2021-2030) and $76 billion in California (2.1 percent of projected average GDP between 2021-2030). But still, these spending levels, amounting to 1-3 percent of GDP, do still mean that something like 97-99 percent of all the state’s economic activity can be devoted to everything else besidesclean energy investments. West Virginia is the one outlier in the states we have studied so far. But even here, we estimate the investment program will need to be only somewhat higher, at 4.2 percent of the state’s projected average GDP for 2021-2030, equal to $3.6 billion per year.