Madeleine Albright ~ Fascisme – Een waarschuwing

Een destructieve kracht met alle kenmerken van het fascisme is in de hele wereld bezig aan een hernieuwde opmars. Freedom House constateert zelfs dat de democratie momenteel ‘belegerd en in aftocht’ is. Aan het eind van de jaren tachtig, toen de Koude Oorlog teneinde kwam, geloofde Madeleine Albright dat de democratie voor eens en altijd had gezegevierd.

Maar bijna dertig jaar later lijkt de loop van de geschiedenis niet langer zeker. Vijftig procent van alle landen in de wereld kan worden beschouwd als een democratie, terwijl de overige 50 procent naar een autoritair systeem neigt. Instituten waar ze heel haar leven op kon rekenen worden aangevallen. Democratische principes worden aan de kant geschoven en de notie ’waarheid’ wordt ontkracht. Madeleine Albright, Secretary of State in de regering van Clinton en voormalig Amerikaans ambassadeur bij de Verenigde Naties, roept de regeringen in Europa en Amerika op de fouten van het verleden niet te herhalen. Buitenlands beleid is en blijft hierbij noodzakelijk waarbij het kerndoel is andere landen te overreden te doen wat wij graag willen dat zij doen, aldus Albright. Dit doel kan worden bereikt met diplomatie, economische sancties en veiligheidsmaatregelen steunen, tot en met militair ingrijpen. Diplomatie is nooit hopeloos, de deur naar onderhandelingen moet altijd open blijven.

De sluipende aanval op de democratie beschrijft Madeleine Albright heel treffend: ‘Mussolini constateerde dat het, als men erop uit is macht te vergaren, verstandig is dat te doen zoals men een kip plukt – veer voor veer – zodat iedere pijnkreet los van elkaar wordt gehoord en het hele proces zo stil mogelijk verloopt.’ Deze tactiek wordt nu ook gebruikt door machthebbers en regeringsleiders die het vertrouwen in verkiezingen, in het rechtssysteem, in de media en de waarheid proberen te ondermijnen. Men verdeelt liever dan verenigt, stelt het najagen van politiek gewin boven alles en het nationalisme wordt weer in ere hersteld. Zij hollen het democratisch politiek systeem uit middels aanvallen op de vrije pers en grondwetswijzigingen die als hervorming worden gepresenteerd. Deze ondemocratische praktijken ziet Albright onder andere in Turkije, Hongarije, Polen en de Filipijnen, bondgenoten van de Verenigde Naties. Ook Amerika, eens de grote verdediger van de democratie, ’begint mogelijk weg te glijden’. Een van de redenen waarom we weer over fascisme praten, aldus Albright, is Donald Trump. ‘Als we fascisme beschouwen als een wond uit het verleden die bijna is geheeld, dan is Trump in het Witte Huis plaatsen zoiets als het verband losrukken en aan de korst krabben.’ Trump is de eerste president in de Verenigde Staten die in woord en daad tegen de democratische idealen ingaat, en zo de waarden van vrijheid, gerechtigheid en vrede verkwanselt. Read more

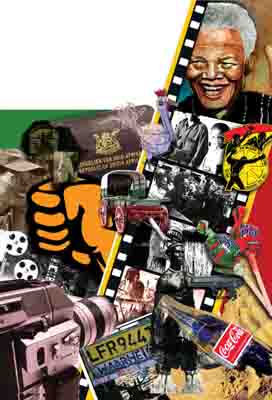

Imaging Africa: Gorillas, Actors And Characters

Africa is defined in the popular imagination by images of wild animals, savage dancing, witchcraft, the Noble Savage, and the Great White Hunter. These images typify the majority of Western and even some South African film fare on Africa.

Africa is defined in the popular imagination by images of wild animals, savage dancing, witchcraft, the Noble Savage, and the Great White Hunter. These images typify the majority of Western and even some South African film fare on Africa.

Although there was much negative representation in these films I will discuss how films set in Africa provided opportunities for black American actors to redefine the way that Africans are imaged in international cinema. I conclude this essay with a discussion of the process of revitalisation of South African cinema after apartheid.

The study of post-apartheid cinema requires a revisionist history that brings us back to pre-apartheid periods, as argued by Isabel Balseiro and Ntongela Masilela (2003) in their book’s title, To Change Reels. The reel that needs changing is the one that most of us were using until Masilela’s New African Movement interventions (2000a/b;2003). This historical recovery has nothing to do with Afrocentricism, essentialism or African nationalisms. Rather, it involved the identification of neglected areas of analysis of how blacks themselves engaged, used and subverted film culture as South Africa lurched towards modernity at the turn of the century. Names already familiar to scholars in early South African history not surprisingly recur in this recovery, Solomon T. Plaatje being the most notable.

It is incorrect that ‘modernity denies history, as the contrast with the past – a constantly changing entity – remains a necessary point of reference’ (Outhwaite 2003: 404). Similarly, Masilela’s (2002b: 232) notion that ‘consciousness of precedent has become very nearly the condition and definition of major artistic works’ calls for a reflection on past intellectual movements in South Africa for a democratic modernity after apartheid. He draws on Thelma Gutsche’s (1972) assumption that film practice is one of the quintessential forms of modernity. However, there could be no such thing as a South African cinema under the modernist conditions of apartheid. This is where modernity’s constant pull towards the future comes into play (Outhwaite 2003). Simultaneous with the necessary break from white domination in film production, or a pull towards the future away from the conditions of apartheid, South Africans will need to re-acquire the ‘consciousness of precedent’, of the intellectual and cultural heritage of the New African Movement, such as is done in Come See the Bioscope (1997) which images Plaatjes’s mobile distribution initiative in the teens of the century. The Movement’s intellectual and cultural accomplishments in establishing a national culture in the context of modernity is a necessary point of reference for the African Renaissance to establish a national cinema in the context of the New South Africa (Masilela 2000b). Following Masilela (ibid.: 235), debates and practices that are of relevance within the New African Movement include:

1. the different structures of portrayal of Shaka in history by Thomas Mofolo and Mazisi Kunene across generic forms and in the context of nationalism and modernity;

2. the discussion and dialogue between Solomon T. Plaatje, H.I.E. Dhlomo, R.V. Selope Thema, H. Selby Msimang and Lewis Nkosi about the construction of the idea of the New African, concerning national identity and cultural identity;

3. the lessons facilitated by Charlotte Manye Maxeke and James Kwegyir Aggrey in making possible the connection between the New Negro modernity and New African modernity;

4. the discourse on the relationship between Marxism and modernity within the context of the Trotskyism of Ben Kies and I.B. Tabata and the Stalinism of Michael Harmel, Albert Nzula and Yusuf Mohammed Dadoo; and

5. the feminist political practices of Helen Joseph, Lilian Ngoyi, Phyllis Ntanatala and others.

Read more

A. Ellian, G. Mollier & B. Rijpkema (Red.)~ De strijd om de democratie. Essays over democratische zelfverdediging

‘De strijd om de democratie’ bevat elf essays, geschreven vanuit een politiek en rechtsfilosofisch perspectief. De democratie en democratische rechtsstaat staan in de hele wereld onder druk. De trias politica wordt ondergraven. In bijna alle Europese landen groeien extreemrechtse en populistische partijen en ‘salafistische groeperingen’ die de democratische rechtsstaat ondermijnen. Waar ligt de grens in zelfverdediging van de democratie als het ernstig wordt bedreigd?

Centraal staat dan ook de weerbaarheid van de democratie, en hoe we ons juridisch kunnen verhouden tot groepen die zich niet houden aan de regels van de rechtsstaat. In het boek wordt een aantal rechtvaardigingen gepresenteerd wanneer mag worden ingrepen. Juridische procedures zijn echter niet voldoende, er moet tevens sprake zijn van een democratische gezindheid, hetgeen voortdurende oefening vereist. Ook worden de EU argumenten aangedragen om zich te bemoeien met de democratische rechtsstaat in de lidstaten. Ze liggen vooral in haar eigen voortbestaan en in het gegeven van een sterk geïntegreerde Europese constitutionele orde, want een aantasting van de nationale constitutionele orde is ook een aantasting van de Europese constitutionele orde. Een weerbare democratie kan ook gevolgen hebben voor de godsdienstvrijheid voor zover het salafistische (en islamitische) organisaties betreft.

Het eerste deel gaat vooral in op de essentie, de grondslagen van de democratie; het tweede deel behandelt de Europese dimensie van een weerbare democratie en het derde deel is gewijd aan de verhouding tussen de vrijheid van godsdienst en het concept van een weerbare democratie.

Bastiaan Rijpkema, docent rechtswetenschap in Leiden, is auteur van het eerste hoofdstuk ‘Democratie als zelfcorrectie revisited’; een aanvulling op zijn eerder in 2015 verschenen en vaak in de andere essays aangehaalde publicatie ‘Weerbare democratie. De grenzen van democratische tolerantie’. Rijpkema baseert zich op de staatsrechtdenker George van den Bergh wiens oratie over antidemocratische partijen uit 1936 vanwege de actualiteit in 2014 opnieuw werd uitgegeven. Van den Bergh beschouwt het vermogen tot zelfcorrectie als het wezen van de democratie. Ook Rijpkema’s uitgangspunt is dat de democratie niet zozeer wordt gevormd door meerderheidsbesluitvorming, maar met name door haar vermogen tot zelfcorrectie: alle besluiten zijn tijdelijk, behalve het besluit om de democratie zelf af te schaffen (als gevolg van een vaak sluipend proces). Het is het enige definitieve besluit in een democratie, en tegen dat onherroepelijke besluit mogen/moeten democratieën zich verzetten. Hij onderscheidt de formele democratie (meerderheidsbesluit), de materiële democratie (meerderheidsbeslissingen plus aantal grondrechten) en vooral dus de democratie als zelfcorrectie.

Om het begrip zelfcorrectie handen en voeten te geven, analyseert hij het Europees Hof voor de Rechten van de Mens (EHRM) en het Duitse Bundesverfassungsgericht, die het begrip democratie concretiseren. Op basis daarvan komt Rijpkema met drie beginselen die het zelfcorrigerende vermogen van de democratie dragen: evaluatie, politieke concurrentie en de vrijheid van meningsuiting. Read more

Organic!

This is a diatribe written for the benefit of those of you who occasionally suffer from bad consciences because you grow roses.

This is a diatribe written for the benefit of those of you who occasionally suffer from bad consciences because you grow roses.

When I met Gerhard Verdoorn he was the Executive Director of Birdlife South Africa. We sat together through a long day devoted to the presentation of the outcomes of research into the harm caused to the environment by pesticides (including fungicides – biologists often don’t discriminate between the two), and at the end of the day, looking for helpful advice, I asked him what he thought I should spray my roses with. He barked one word in answer: “Roundup!”

Given the facts that roses are exotics in the southern hemisphere, that they will not grow down here unless you fertilise and spray them, that fertilisers and sprays undoubtedly harm the environment, that the environment is in trouble and needs to be cosseted, and that global warming is going on the one hand to parch our lands (through chronic droughts) and on the other hand to drown them (through raising the level of the seas), Professor Verdoorn’s response to me would seem to be fully justified. But it only SEEMS to be justified. In reality, it was either witty or rude, depending on your frame of mind at the time, but not at all justified. There are about seven billion people in the world. If we didn’t use fertilisers, insecticides and fungicides, we could feed about four billion of them.

Kishore Mahbubani – Is het Westen de weg kwijt? Een provocatie

Van het jaar 1 tot het jaar 1820 waren China en India de twee grootste economieën. Pas in de afgelopen tweehonderd jaar werden Europa en America succesvol. Er is geen westerse leider die durft te zeggen dat er nu aan een periode van westerse hegemonie een einde komt. Het Westen kan niet langer zijn wil opleggen aan de wereld. China en India hebben hun economische aandeel heroverd; het westerse aandeel in de wereldeconomie zal alleen maar verder slinken. Het Westen domineert niet meer. Het is van groot belang zich hieraan aan te passen, een concurrerende mondiale strategie te ontwikkelen. Van een coherente strategie om met de nieuwe situatie om te gaan is echter geen sprake. In plaats daarvan slaat het Westen wild om zich heen door Irak aan te vallen, Syrië te bombarderen, Rusland sancties op te leggen en China op te hitsen. Het moet leren zijn huidige positie te delen of zelfs af te staan.

Gaat dat lukken? Het klinkt paradoxaal, maar alleen door de neergang te erkennen kan het Westen op lange termijn succesvol blijven, zo betoogt Kishore Mahbubani. Het Westen heeft ‘een dosis Machiavelli’ nodig, door het voortouw te nemen bij de introductie van een nieuwe orde. Een machiavellistische, pragmatische moraal boven een idealistische of dogmatische moraal.

Objectief gezien heeft de mensheid er nooit zo goed voorgestaan en dat is grotendeels te danken aan westerse praktijken en westerse ideeën die invloed hebben gehad op andere samenlevingen. Het grootste geschenk van het Westen is het redeneervermogen, waardoor het persoonlijk welzijn is verbeterd. De verspreiding van het westerse redeneervermogen heeft drie stille revoluties op gang gezet die het grote succes van niet-westerse samenlevingen verklaren. De eerste revolutie is van politieke aard, het verzet tegen het feodale systeem, waardoor de meeste Aziatische leiders begrepen dat ze rekenschap aan hun volk moesten afleggen en niet omgekeerd, hetgeen o.a. het grote succes van China verklaart. De tweede revolutie is van psychologische aard: men is erin gaan geloven dat men zelf het heft in handen kan nemen en via de ratio een beter resultaat kan krijgen. De derde revolutie is van bestuurlijke aard: via deugdelijk rationeel bestuur verandert de samenleving in positieve zin. Goed bestuur kan de samenleving transformeren en verheffen.

De ervaringen met rationeel goed bestuur maken de inwoners van China, India en Indonesië optimistischer dan de westerse burger. Negentig procent van de jongeren zien de technologie als de factor die hoop geeft voor de toekomst.

De twee wereldoorlogen en 11 september hebben het Westen afgeleid. Zij hebben bijvoorbeeld niet gezien dat niet 11 september de belangrijkste gebeurtenis was met verstrekkende gevolgen, maar de toetreding van China tot de Wereldhandelsorganisatie, hetgeen in het Westen leidde tot ‘creatieve destructie’ en een verlies van grote aantallen banen, aldus Mahbubani. Hierdoor nam de ongelijkheid binnen westerse economieën toe en dat veroorzaakte weer Brexit en dat Trump aan de macht kwam. Alhoewel de massa de westerse elite wantrouwt, denkt ze dat ze nog steeds gelijk heeft. Dat het Westen aan macht verliest toont Mahbubani aan met vooral economische gegevens: in 2050 zal het koopkrachtpariteit van de G7 zijn geslonken van 31,5 procent in 2015 naar 20 procent en dat van E7 zou zijn toegenomen van 36,3 procent naar 50 procent (bron PricewaterhouseCoopers). Maar deze gegevens bieden ook inzicht in “het uitbannen van menselijke ellende en een toename van het menselijk geluk.” De wereldwijde opmars van functioneel bestuur, vinden alleen niet plaats in Noord-Afrika en het Midden-Oosten, regio’s waar het Westen zich mee heeft bemoeid, aldus Mahbubani. “Dankzij functioneel bestuur, redeneervermogen en intelligente, welgestelde inwoners zullen oorlogen blijven afnemen, komt geweld minder vaak voor en zullen economieën gestaag blijven groeien.” Een historisch keerpunt waarbij de informatierevolutie een grote positieve rol speelt. Read more

The Resurgence Of Political Authoritarianism: An Interview With Noam Chomsky

Following the end of World War II, liberal democracy began to flourish in most countries in the Western world, and its institutions and values were aspired to by movements and individuals under authoritarian and oppressive regimes. However, with the rise of neoliberalism, both the institutions and the values of modern democracy came rapidly and continuously under attack in an effort to extend the profit-maximizing logic and practices of capitalism throughout all aspects of economic and social life.

Sketched out in broad outlines, this story explains the resurgence of authoritarian political trends in today’s Western societies, including the rise of far-right movements whose followers feel threatened by the processes unleashed by neoliberal economic policies. In the former communist countries and in the non-Western world, meanwhile, authoritarianism is also on the rise, partly as a residue of authoritarian legacies, and partly as a reaction to perceived threats posed to national culture and social order by global capitalism.

Is it possible to counter this rise in extreme populism? In this exclusive Truthout interview, the world-renowned linguist and public intellectual Noam Chomsky — the author of more than 100 books and thousands of academic articles and popular essays — offers his unique insights on this and more, bringing into the analysis issues and questions that are rarely addressed in the current debates taking place today about the resurgence of political authoritarianism.

C.J. Polychroniou: In 1992, Francis Fukuyama published an intellectually embarrassing book titled The End of History and the Last Man, in which he prophesied the “end of history” after the collapse of the communist bloc, arguing that liberal democracy would become the world’s “final form of human government.” However, what has happened in this decade in particular is that the institutions and values of liberal democracy have come under attack by scores of authoritarian leaders all over the world, and extreme nationalism, xenophobia and “soft fascist” tendencies have begun reshaping the political landscape in Europe and the United States. How do you explain the resurgence of political authoritarianism in the early part of the 21st century?

Noam Chomsky: The “political landscape” is indeed ominous. While today’s political and social circumstances are much less dire, still they do call to mind Antonio Gramsci’s warning from Mussolini’s prison cells about the severe crisis of his day, which “consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born [and] in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.”

One morbid symptom is the resurgence of political authoritarianism, a highly important matter that is properly receiving a great deal of attention in public debate. But “a great deal of public attention” should always be a warning sign: Does the shaping of the issues reflect power interests, which are diverting attention from what may be more significant factors behind the general concerns? In the present case, I think that is so, and before turning to the very significant question of the resurgence of political authoritarianism, I’d like to bring up related matters that do not seem to me to receive the attention they merit, and in fact are almost totally excluded from the extensive public attention.

It’s entirely true that “the institutions and values of liberal democracy are under attack” to an unusual extent, but not only by authoritarian leaders, and not for the first time. I presume all would agree that primary among the values of liberal democracy is that governments should be responsive to voters. If that is not the case, “liberal democracy” is a farce. Read more