Hannah Arendt’s Theory of Totalitarianism – Part One

Hannah Arendt wrote The Origins of Totalitarianism in 1949, by which time the world had been confronted with evidence of the Nazi apparatus of terror and destruction. The revelations of the atrocities were met with a high degree of incredulous probing despite a considerable body of evidence and a vast caché of recorded images. The individual capacity for comprehension was overwhelmed, and the nature and extent of these programmes added to the surreal nature of the revelations. In the case of the dedicated death camps of the so-called Aktion Reinhard, comparatively sparse documentation and very low survival rates obscured their significance in the immediate post-war years. The remaining death camps, Majdanek and Auschwitz, were both captured virtually intact. They were thus widely reported, whereas public knowledge of Auschwitz was already widespread in Germany and the Allied countries during the war.[i] In the case of Auschwitz, the evidence was lodged in still largely intact and meticulous archives. Nonetheless it had the effect of throwing into relief the machinery of destruction rather than its anonymous victims, for the extermination system had not only eliminated human biological life but had also systematically expunged cumulative life histories and any trace of prior existence whatsoever, ending with the destruction of almost all traces of the dedicated extermination camps themselves, just prior to the Soviet invasion.

Although Arendt does not view genocide as a condition of totalitarian rule, she does argue that the ‘totalitarian methods of domination’ are uniquely suited to programmes of mass extermination (Arendt 1979: 440). Moreover, unlike previous regimes of terror, totalitarianism does not merely aim to eliminate physical life. Rather, ‘total terror’ is preceded by the abolition of civil and political rights, exclusion from public life, confiscation of property and, finally, the deportation and murder of entire extended families and their surrounding communities. In other words, total terror aims to eliminate the total life-world of the species, leaving few survivors either willing or able to relate their stories. In the case of the Nazi genocide, widespread complicity in Germany and the occupied territories meant that non-Jews were reluctant to share their knowledge or relate their experiences – an ingenious strategy that was seriously challenged only by Germany’s post-war generation coming to maturity during the 1960s. Conversely, many survivors were disinclined to speak out. Often, memories had become repressed for fear that they would not be believed, out of the ‘shame’ of survival, or because of the trauma suffered. Incredulity was thus both a prevalent and understandable human reaction to the attempted total destruction of entire peoples, and in the post-war era the success of this Nazi strategy reinforced a culture of denial that perpetuated the victimisation of the survivors. In The Drowned and the Saved Primo Levi records the prescient words of one of his persecutors in Auschwitz:

However this war may end, we have won the war against you; none of you will be left to bear witness, but even if someone were to survive, the world will not believe him. There will be perhaps suspicions, discussions, research by historians, but there will be no certainties, because we will destroy the evidence together with you. (Levi 1988: 11)

Here was unambiguous proof of the sheer ‘logicality’ of systematic genocide. The silence following the war was therefore quite literal, and the publication of Origins in 1951 could not and did not set out to bridge that chasm in the human imagination. It did, however, establish Arendt as the most authoritative and controversial theorist of the totalitarian. Read more

Hannah Arendt’s Theory of Totalitarianism – Part Two

Ideology and terror: The experiment in total domination

In chapter two of Hannah Arendt’s Response to the Crisis of her Time it was argued that Arendt’s typology of government rests on the twin criteria of organisational form and a corresponding ‘principle of action’. In the post-Origins essay On the Nature of Totalitarianism, Arendt argues that Western political thought has customarily distinguished between ‘lawful’ and ‘lawless’, or ‘constitutional’ and ‘tyrannical’ forms of government (Arendt 1954a: 340). Throughout Occidental history, lawless forms of government, such as tyranny, have been regarded as perverted by definition. Hence, if

… the essence of government is defined as lawfulness, and if it is understood that laws are the stabilizing forces in the public affairs of men (as indeed it always has been since Plato invoked Zeus, the god of the boundaries, in his Laws), then the problem of movement of the body politic and the actions of its citizens arises. (Arendt 1979: 466-7)

‘Lawfulness’ as a corollary of constitutional forms of government is a negative criterion inasmuch as it prescribes the limits to but cannot explain the motive force of human actions: ‘the greatness, but also the perplexity of laws in free societies is that they only tell what one should not, but never what one should do’ (ibid.: 467). Arendt, accordingly, lays great store by Montesquieu’s discovery of the ‘principle of action’ ruling the actions of both government and governed: ‘virtue’ in a republic, ‘honour’ in monarchy, and ‘fear’ in tyrannical forms of government (Arendt 1954a: 330; Arendt 1979: 467-8).

In all non-totalitarian systems of government, therefore, the principle of action is a guide to individual actions, although fear in tyranny is ‘precisely despair over the impossibility of action’ since tyranny destroys the public realm of politics and is therefore anti-political by definition. Nevertheless, the state of ‘isolation’ and ‘impotence’ experienced by the individual in tyrannical forms of government springs from the destruction of the public realm of politics whereas the mobilisation of the ‘overwhelming, combined power of all others against his own’ (Arendt 1954a: 337) does not eliminate entirely a minimum of human contact in the non-political spheres of social intercourse and private life. Thus, if the fear-guided actions of the subject of tyrannical rule are bereft of the capacity to establish relations of power between individuals acting and speaking together in a public realm of politics, the ‘isolation’ of the political subject does not entail the destruction of his social and private relations (ibid.: 344). Therefore, in all non-totalitarian forms of government, the body politic is in constant motion within set boundaries of a stable political order, although tyranny destroys the public space of political action (Arendt 1979: 467).

In all non-totalitarian systems of government, therefore, the principle of action is a guide to individual actions, although fear in tyranny is ‘precisely despair over the impossibility of action’ since tyranny destroys the public realm of politics and is therefore anti-political by definition. Nevertheless, the state of ‘isolation’ and ‘impotence’ experienced by the individual in tyrannical forms of government springs from the destruction of the public realm of politics whereas the mobilisation of the ‘overwhelming, combined power of all others against his own’ (Arendt 1954a: 337) does not eliminate entirely a minimum of human contact in the non-political spheres of social intercourse and private life. Thus, if the fear-guided actions of the subject of tyrannical rule are bereft of the capacity to establish relations of power between individuals acting and speaking together in a public realm of politics, the ‘isolation’ of the political subject does not entail the destruction of his social and private relations (ibid.: 344). Therefore, in all non-totalitarian forms of government, the body politic is in constant motion within set boundaries of a stable political order, although tyranny destroys the public space of political action (Arendt 1979: 467).

Arendt argues that totalitarianism is distinguished from all historical forms of government, including tyranny, insofar as it has no use for any ‘principle of action taken from the realm of human action’, since the essence of its body politic is ‘motion implemented by terror’ (Arendt 1954a: 348; see 331-3). In other words, totalitarianism aims to eradicate entirely the human capacity to act as such (Arendt 1979: 467). For totalitarian rule targets the total life-world of its subjects, which in turn presupposes a world totally conquered by a single totalitarian movement.[i] Hence, only in

… a perfect totalitarian government, where all men have become ‘One Man’, where all action aims at the acceleration of the movement of nature or history, where every single act is the execution of a death sentence which Nature or History has already pronounced, that is, under conditions where terror can be completely relied upon to keep the movement in constant motion, no principle of action separate from its essence would be needed at all. (ibid.)

This important passage contains several key ideas that need to be carefully unpacked. Firstly, we encounter Arendt’s conception of society reduced to ‘One Man’ or a single, undifferentiated Mankind as a condition of a ‘perfect totalitarian government’. We may note here that totalitarianism thus conceived constitutes the very antithesis of the political in Arendt’s sense of men acting and speaking together in a public realm of politics. Secondly, Arendt contends that only in such a perfect totalitarian system would terror, which she views as the ‘essence’ of totalitarianism, suffice to sustain totalitarian rule. Hence, in all imperfect totalitarian dictatorships, terror in its dual function as the ‘essence of government and principle, not of action, but of motion’ (ibid.), is an insufficient condition of totalitarian rule. For, insofar as totalitarianism has not completely eliminated all forms of spontaneous human action, freedom, or the inherent human capacity to ‘make a new beginning’, exists as an ever-present potential within society (ibid.: 466).[ii] Totalitarian movements must therefore strive to eliminate this capacity for political action, and any form of spontaneous human relations. Hence:

What totalitarian rule needs to guide the behaviour of its subjects is a preparation to fit each of them equally well for the role of executioner and the role of victim. This two-sided preparation, the substitute for a principle of action, is the ideology. (ibid.: 468)

However – and this is a crucial point – Arendt stresses that it is

… in the nature of ideological politics … that the real content of the ideology (the working class or the Germanic peoples), which originally had brought about the ‘idea’ (the struggle of classes as the law of history or the struggle of races as the law of nature), is devoured by the logic with which the ‘idea’ is carried out. (Arendt 1979: 472) Read more

Hannah Arendt – Zur Person – Full Interview (with English Subtitles)

Hannah Arendt in the Rozenberg Quarterly

Anthony Court – Hannah Arendt’s Theory of Totalitarianism. Part One: http://rozenbergquarterly.com/?p=3099

Anthony Court – Hannah Arendt’s Theory of Totalitarianism. Part Two: http://rozenbergquarterly.com/?p=3115

Nima Emami – Hannah Arendt and The Green Movement: http://rozenbergquarterly.com/?p=563

Large Archive Of Hannah Arendt’s Papers Digitized By The Library Of Congress: Read Her Lectures, Drafts Of Articles, Notes & Correspondence

Many people read the German-Jewish political philosopher and journalist Hannah Arendt as something of an oracle, a secular prophet whose most famous works—her essay on the trial of Adolf Eichmann and her 1951 Origins of Totalitarianism—contain secrets about our own times of high nationalist fervor. And indeed they may, but we should also keep in mind that Arendt’s insights into the horrors of Nazism did not emerge until after the war.

Arendt did not identify as Jewish during the Nazi’s rise to power, but as a fully assimilated German; she had a romantic relationship with her professor Martin Heidegger, who became a doctrinaire Nazi, and she seemed to have little understanding of German antisemitism during the thirties and forties. Arendt, many have alleged, sometimes seemed too close to her subject.

The archives: http://www.openculture.com/2014/02/hannah-arendt-archives.html

Josephat Stephen Itika ~ Fundamentals Of Human Resource Management: Emerging Experiences From Africa

‘Leaders must be guided by rules which lead to success.’ (Machiavelli: The Prince)

‘Leaders must be guided by rules which lead to success.’ (Machiavelli: The Prince)

Foreword

For over half a century now, most African people south of the Sahara are still living under political, social and economic hardships, which cannot be compared with the rest of the world. For many, the expectations of independence have remained a dream. This state of affairs has many explanations but it is fundamentally based on the nature of African countries and organisations on one hand, and on the other hand there is over reliance on Eurocentric philosophies, theories, and assumptions on how administrators and managers should manage African countries, organisations, and people in such a way that will lead to prosperity. As a result, the same Eurocentric mindsets are used to develop solutions for African leaders and managers through knowledge codification and dissemination in the form of textbooks and the curricula in education systems.

Evidence from economies in South East Asian countries suggests that the success behind these countries is largely explained by high investment in human capital and, to some extent, avoiding wholesale reliance on the importing of northern concepts, values and ways of managing people; that is, the development of human resources capable of demonstrating management in setting and pursuing national, sector wide, and corporate vision, strategies, and commitment to a common cause within the context of their own countries and organisations. Similarly, African managers and leaders effectively cannot manage by merely importing Eurocentric knowledge without critical reflection, sorting and adaptation to suit the context they work in and with cautious understanding of the implications of globalisation in their day-to-day management practices. They have to understand and carefully interpret northern concepts and embedded assumptions, internalise and develop the best strategies and techniques for using them to address management problems in their organisations and countries, which are, by and large, Afrocentric.

Therefore, like Machiavelli, human resource managers, like leaders, must be guided by rules which lead to the success of their countries and organisations. The main challenge facing human resource managers now is to know which rules are necessary and when applied would lead to effective human resource management results in different types of public and private sector organisations and contexts. This is a difficult question to answer. However, we can start by learning one small step at a time from the emerging experiences of our own practices of human resource management in Africa and elsewhere.

This book on ‘Fundamentals of human resource management: Emerging Experiences from African Countries’ has just made a small step in the journey of establishing a link between Eurocentric concepts, philosophies, values, theories, principles and techniques in human resource management and understanding of what is happening in African organisations. This will form part of the groundwork of unpacking what works and what does not work well in African organisational contexts and shed more light on emerging synergistic lessons for the future. The book has fourteen chapters each addressing important issues in human resource management in terms of the Eurocentric approach and reflecting on what is happening in African governments and organisations at the end of each chapter.

Read more

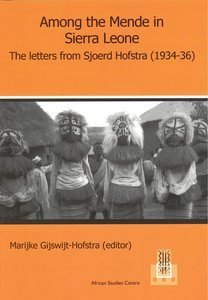

Marijke Gijswijt‐Hofstra (Ed.& transl.) ~ Among The Mende In Sierra Leone: The Letters From Sjoerd Hofstra (1934-36)

This book offers a unique look behind the scenes of anthropological fieldwork amongst the Mende in Sierra Leone in the mid-1930s. The Dutch anthropologist and sociologist Sjoerd Hofstra (1898-1983), Rockefeller research fellow of the International Institute of African Languages and Cultures and one of Bronislaw Malinowski’s three ‘Mandarins’ (as were also Meyer Fortes and S. Frederick Nadel), reports in long, bi-weekly letters to his adoptive mother about his experiences with the Mende. During his first stay in Sierra Leone (January 1934 – March 1935), Hofstra got blackwater fever, a complication of malaria tropica. His second stay (May – September 1936) came to an untimely end because he again developed symptoms of blackwater fever and was advised to return to Europe. Because of this his fieldwork remained unfinished, and Hofstra never got round to publishing the planned book on the Mende. However, Hofstra published four articles on the Mende in English, photocopies of which are included in this book. Next to these articles Hofstra’s letters to his adoptive mother contain valuable first-hand information about his fieldwork. His daughter, cultural and social historian Marijke Gijswijt-Hofstra, has edited and translated these letters, while also including contextual information.

This book offers a unique look behind the scenes of anthropological fieldwork amongst the Mende in Sierra Leone in the mid-1930s. The Dutch anthropologist and sociologist Sjoerd Hofstra (1898-1983), Rockefeller research fellow of the International Institute of African Languages and Cultures and one of Bronislaw Malinowski’s three ‘Mandarins’ (as were also Meyer Fortes and S. Frederick Nadel), reports in long, bi-weekly letters to his adoptive mother about his experiences with the Mende. During his first stay in Sierra Leone (January 1934 – March 1935), Hofstra got blackwater fever, a complication of malaria tropica. His second stay (May – September 1936) came to an untimely end because he again developed symptoms of blackwater fever and was advised to return to Europe. Because of this his fieldwork remained unfinished, and Hofstra never got round to publishing the planned book on the Mende. However, Hofstra published four articles on the Mende in English, photocopies of which are included in this book. Next to these articles Hofstra’s letters to his adoptive mother contain valuable first-hand information about his fieldwork. His daughter, cultural and social historian Marijke Gijswijt-Hofstra, has edited and translated these letters, while also including contextual information.

ASC Occasional Publication 19 – ISBN: 978‐90‐5448‐138‐6 – 2014

Download book (PDF): https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/handle/1887/24890