How Can Gov. McCrory’s Proposal Work? Preliminary Thoughts And Policy Considerations

On Monday, March 30, the Winston-Salem Journal published a piece titled “Economic development bill stalls in Senate” starting with Gov. McCrory’s proposal to “recruit an automobile manufacturer and create thousands of jobs and scores of companies”. This is really an interesting development proposal that can boost production growth in North Carolina. The article [i] seeks to discuss the developmental and industrial dimensions of this proposal and to offer policy considerations deemed absolutely necessary for the successful implementation of such an ambitious plan.

The Present Context

There has been much talk and debate on the recent economic downfall of the United States. Causes for concern include persistent fluctuations in output, job creation and productivity; massive federal budget and trade account deficits; and issues associated with “capital flight” and industrial decline (U.S. National Economic Accounts, various years). These fluctuations are closely linked to unutilized labor force, lost output, and social problems. Furthermore, the economic effects of the recent financial crisis are complicated and far-reaching because of simultaneous shocks in the housing, stock, and labor markets. Actual spending, unemployment, home equity, well-being, emotional and physical health, and expectations about the future have all been affected by a significant slowdown in endogenous productive activity and various problems associated with financial markets. Hence, it is argued here that three important themes need to come to the center stage:

1. A discourse on the “appropriate” policy interventions,

2. The importance of adopting a long-term perspective, and

3. Emphasis on strengthening local production lines.

An Alternative Development Paradigm

The US model of a pluralist market economy is strongly consumer and short-term oriented. Its strength is dynamism and flexibility; its dominant philosophy is private sector competition and minimal government. As a result, industrial policy has not been developed in a systematic or coherent fashion as an important piece of policy making, and the country has not generally seen itself as being involved in the promotion of specific sectors. Read more

Civil Domains and Arenas in Zimbabwean Settings. Democracy and Responsiveness Revisited – DPRN Five

Introduction (written 2008 – first published 2010)

A popular remedy for Africa’s predicament is the promotion of ‘civil society’. It is conventionally seen as a collection of various kinds of non-profit bodies separate from the state and business sector. It is framed within a consensual model of politics, and thus capable of working in ‘partnership’ with both state and business sectors in pursuit of common interests, particularly ‘development’ and ‘democracy’ [i]. Since the late 1970s donors sought substitutes for the state in the private sector. In the 1980s they discovered the virtues of the non-profit branch of this sector. They tasked older entities such as mission hospitals and newly-arrived non-governmental organisations (NGOs) with providing a range of services, from schooling and healthcare to small enterprise promotion, that were once considered responsibilities of the public sector.

Under their neoliberal paradigm, donors have tried to raise the nonprofit sector’s political status. Beyond service provision, its main task is to counter government power. Here civil society is cast as a hero, who routinely calls a villainous state to account. Yet this model of ‘civil society’ has evoked controversy. Questions have arisen about the effects of NGOs not only as substitute providers of basic services, but also as vehicles of public politics, effectively substituting for opposition political parties [ii]. A number of writers have called attention to ‘the obvious: that civil society is [largely] made up of international organisations’. Some argue that the whole concept of ‘civil society’ as promoted by outsiders does not match African sociological or political realities, and can ultimately weaken, rather than strengthen the power of common citizens. There are calls, in short, for a re-think. Read more

Post-Apartheid South Africa And The Crisis Of Expectation – DPRN Four

The collapse of the apartheid state and the ushering in of democratic rule in 1994 represented a new beginning for the new South Africa and the Southern African region. There were widespread expectations and hopes that the elaboration of democratic institutions would also inaugurate policies that would progressively alleviate poverty and inequality.

Fourteen years into the momentous events that saw Nelson Mandela become the president of South Africa, critical questions are being asked about the country’s transition, especially about its performance in meeting the targets laid down in its own macro-economic programmes in terms of poverty and inequality, and the consequences of the fact that the expectations of South Africans have not been met.

At a general level the euphoria of 1994 has come up against deepening inequality, rising unemployment, the HIV pandemic and bourgeoning violent crime. The latter has led one writer to conclude that South Africa is ‘a country at war with itself’ (Altbeker 2007).

South Africans have trusted democracy with the hard task to deliver jobs, wealth, healthcare, better housing and services to the people. But now that all of this is slow in arriving, there is growing disquiet and increased community protests that have sought to challenge the government on the pace of service delivery.

It is the level of what we have labelled a crisis of expectation that this paper speaks to. It looks at what under lies this crisis of expectation and what are the potential consequences. Read more

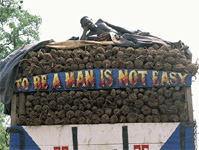

To Be A Man Is Not Easy ~ Stories From Ghanaian Emigrants. Contents & Introduction

Introduction – see below

1. The good samaritan who follows where the money is. Interview with Owusu Agyeman

2. Dollars in the wall. Interview with Mr. Babbs Haruna from Nkoranza

3. A scar reminds me of the day I wept. Interview with Kwame Baffo

4. My hotel! Interview with Michael Sarpong

5. The boys of the band. Interview with Akosua Asantewaah

6. Peace of mind or success? I want it both. Interview with Kojo Apiah Kubi. (Brian Osanhene Duako in Chicago)

7. It is love for one another that makes us continue. Interview with Kojo Sampson

8. I saw dead people covered in dust. passport on top. Interview with Mr. Darko from Nkoranza

9. No other treats than daily fresh insults. Interview with Yaw Charles from Nkoranza

10. I want to get a life but I cant because I am waiting. Interview with Richard Kwasi Ntim

11. Mercy, the girl with the red leggings

12. Education, solidarity and being able to say no. Interview with Matthew Essieh

13. Caught between two worlds. Interview with Samuel Oteng

14. The conference participant. Interview with Osei Takyi

Introduction

Why this book? It all started with Kwame Baffoe, the guy who only wept once. Kwame was the hospital driver at the time that I worked as a tropical doctor at Nkoranza Hospital. One day Baffoe disappeared. After two weeks his relatives came to ask for his end of service benefit. I was then the medical director as well as the administrator and I had to say No, he vacated his post so sorry, no. But where for God’s sake is Baffoe? They silently left. This was in the mid-eighties. Read more

To Be A Man Is Not Easy ~ The Good Samaritan Who Follows Where The Money Is. Interview With Owusu Agyeman

I am Owusu Agyeman and I come from from Akropong in the Nkoranza district. I live here in Nkoranza town where I have my well known Ash-foam business. I sell pillows and mattresses. As you may know, my father is a chief.

I am Owusu Agyeman and I come from from Akropong in the Nkoranza district. I live here in Nkoranza town where I have my well known Ash-foam business. I sell pillows and mattresses. As you may know, my father is a chief.

I decided to go to Libya because there is no work in Ghana. Let me correct myself and say it this way: there is work in Ghana but it doesn’t fetch any money. Take farming for example. I may use two million Cedis to prepare and sow the land and when I harvest my corn I may get 1,5 million in return. What does it mean? It means I lost. I have lost money because the market prices are bad. That is why I went abroad, to get enough money to start a business in Ghana.

At the time when I left Ghana I was no longer a young boy, I was thirty eight years old and had a wife and three children. My wife agreed that I should go in order to provide for the family. So then we had to prepare for such a journey which is both costly and dangerous. Danger is everywhere along the way but the walking, which we call footing, through the desert, that is the greatest risk! I will tell you the story of my journey. I started here in Nkoranza in Ghana and traveled in an ordinary lorry to the border at Bawku.

I then took a car across the border to Burkino Faso and then on to Mali. Finally I went deep into Niger where you reach the desert and then another chapter starts! Those days when I traveled there, there was no such thing as group transport with Ghanaians all the way to Libya. Not at that time. Now that has changed.

Africans need no visa on the West-African continent so I had all I needed which was my passport, my vaccination card and enough money. The last one is the hardest! At border crossings I of course never tell my real plans of going to Libya for they would send me right back. So at the Ghana border I say I go to Burkina Faso to work and from Burkina Faso I say I go to work at Mali. I have a profession. I am a mechanic. So that’s what I say: I am going to work there as a mechanic. Once in Mali they ask me where I am going and I say to Niamey in Niger. I went to Niamey and then to the second biggest city which is called Agadez. I did all this with ordinary local passenger cars. It is at Agadez that the story changes!

Here you have reached the desert. Here we sit and rest along the roadside and we wait. We wait for other people who are on their way to Libya. Once there are enough people to fill a car then you go across the desert. The cars are land-cruisers, pick-ups.

Niger is a poorer country than Ghana, no jobs. There are men there in Agadez who make a living out of assembling people and organizing a car for them. There are other men who make it their job to cross the desert with us and bring us to Libya. Two of these men sit in the cabin in front and all of us travelers are packed in the back of the pickup. In my case they took us, 90 to 100 persons, into two cars. At that time, 1997, they let us pay 20,000 CFA, which is about 50 dollar per person. We were packed like maize bags, sometimes they even got more than 50 people in one land-cruiser. Read more

The Postman Only Had To Ring Once

What a beautiful public love letter to an art that appears to be lost, but not quite. This writer, sharing his thoughts with who knows who, also longs for the intimacy of the exchange of words between two. What strikes me most about this essay are the words: “The day I lost one of J.’s illustrated postcards in the subway on my way home, I was as distraught as I would be now if my hard disk crashed.”

What a beautiful public love letter to an art that appears to be lost, but not quite. This writer, sharing his thoughts with who knows who, also longs for the intimacy of the exchange of words between two. What strikes me most about this essay are the words: “The day I lost one of J.’s illustrated postcards in the subway on my way home, I was as distraught as I would be now if my hard disk crashed.”

No, I would not say like “my hard disk” crashing. Not that at all. That least of all. That is an anxiety unique to this age of data-exchange, the reduction of all words, whether committed to hard-drive with care or hastily-strung-together, to an assemblage of giga-bytes. That feeling is equivalent to the boss berating you for losing an “important document”, no matter how important to you this hard-drive may be.

I have kept letters that are close to my heart, letters that mark milestones in my life and recollect those in the lives of those for whom I care, those who I remember, whether or not they remember me. I have lost some of these, in the jumble of our “modern” state of statelessness, placelessness. With each loss I knew I had lost a marker. Not that the object itself was a loss it itself. It was a loss because it has meaning in and of itself. The words, which were written with care and thought, sometimes in friendship, at times in love, are irreplaceable in a way that a hard-drive could never be. Letters brought more than news, or, rather, they defined a notion of news that many no longer regard as relevant. The postman only had to ring once.

Dropping these fragments in the subway would mean losing a piece of the dialogue that once existed, a fragment that could not have been spoken in words, and which cannot ever be committed to memory in the way that we can store passwords to social media sites, the literary equivalent of fifty shades of grey. Not even the spoken word can “reveal” itself in the immediacy of dialogue. We need to filter the maelstrom of spoken intonations, throw away thoughts, carelessly aimed barbs, fluff. In other words, we need to “process”, in the pseudo lingo of the day, as if the spoken word is something to receive like a legal brief, rather than to share in a collective act of interpretation.

So perhaps it is not only the written word that is fading, the medium for committing our most intimate thoughts. With that loss we risk losing the art of listening, rather than merely hearing as one does in a noisy room. We have turned listening into hearing, the ear into a portal to matter, and that extraordinary matter into a measurement of our relative sanity. Who has not heard the claim that we use perhaps 12-15% of our brains, “on average”? What better measure of our language of median lines. In this age of brain science thought, itself is losing its tragic quality, as we learn that the biological organ with which we think is also the locus of our deepest emotions, and we again take refuge in “spirit” to quell a fear inspired by our eternal finitude. Hang onto those letters and postcards. The brain has a sell-by date. The words it shapes into a personal declaration between two people do not.

About the author

Prof.dr. Anthony Court – Researcher, Genocide Studies, University of South Africa