Chomsky: Let’s Focus On Preventing Nuclear War, Rather Than Debating “Just War”

NATO leaders announced Wednesday that the alliance plans to reinforce its eastern front by deploying many more troops in countries like Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia — including thousands of U.S. troops — and sending “equipment to help Ukraine defend itself against chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear threats.” And while the NATO alliance itself is not directly providing weapons to Ukraine, many of its member countries are pouring weapons into Ukraine, including missiles, rockets, machine guns, and more.

In all likelihood, Russian President Vladimir Putin believed that his military would overrun Ukraine within a matter of a few days on February 24, when he ordered an invasion into the neighboring country after a long and massive military buildup on Ukraine’s border.

A month later, however, the war is still raging, and several Ukrainian cities have been devastated by Russian air attacks. Peace talks have stalled, and it is unclear whether Putin still wants to overthrow the government or is instead aiming now for a “neutral” Ukraine.

In the interview that follows, world-renowned scholar and leading dissident voice Noam Chomsky shares his thoughts and insights about the available options for an end to the war in Ukraine, and ponders the idea of “just” war and whether the war in Ukraine could potentially lead to the collapse of Putin’s regime.

Chomsky is internationally recognized as one of the most important intellectuals alive. His intellectual stature has been compared to that of Galileo, Newton and Descartes, as his work has had tremendous influence on a variety of areas of scholarly and scientific inquiry, including linguistics, logic and mathematics, computer science, psychology, media studies, philosophy, politics and international affairs. He is the author of some 150 books and the recipient of scores of highly prestigious awards, including the Sydney Peace Prize and the Kyoto Prize (Japan’s equivalent of the Nobel Prize), and of dozens of honorary doctorate degrees from the world’s most renowned universities. Chomsky is Institute Professor Emeritus at MIT and currently Laureate Professor at the University of Arizona.

C.J. Polychroniou: Noam, we are already a month into the war in Ukraine and peace talks have stalled. In fact, Putin is turning up the volume on violence as the West increases military aid to Ukraine. In a previous interview, you compared Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to the Nazi invasion of Poland. Is Putin’s strategy then straight out of Hitler’s playbook? Does he want to occupy all of Ukraine? Is he trying to rebuild the Russian empire? Is this why peace negotiations have stalled?

Noam Chomsky: There is very little credible information about the negotiations. Some of the information leaking out sounds mildly optimistic. There is good reason to suppose that if the U.S. were to agree to participate seriously, with a constructive program, the possibilities for an end to the horror would be enhanced.

What a constructive program would be, at least in general outline, is no secret. The primary element is commitment to neutrality for Ukraine: no membership in a hostile military alliance, no hosting of weapons aimed at Russia (even those misleadingly called “defensive”), no military maneuvers with hostile military forces.

That would hardly be something new in world affairs, even where nothing formal exists. Everyone understands that Mexico cannot join a Chinese-run military alliance, emplace Chinese weapons aimed at the U.S. and carry out military maneuvers with the People’s Liberation Army.

In brief, a constructive program would be about the opposite of the Joint Statement on the U.S.-Ukraine Strategic Partnership signed by the White House on September 1, 2021. This document, which received little notice, forcefully declared that the door for Ukraine to join NATO (the North Atlantic Treaty Organization) is wide open. It also “finalized a Strategic Defense Framework that creates a foundation for the enhancement of U.S.-Ukraine strategic defense and security cooperation” by providing Ukraine with advanced anti-tank and other weapons along with a “robust training and exercise program in keeping with Ukraine’s status as a NATO Enhanced Opportunities Partner.”

The statement was another purposeful exercise in poking the bear in the eye. It is another contribution to a process that NATO (meaning Washington) has been perfecting since Bill Clinton’s 1998 violation of George H.W. Bush’s firm pledge not to expand NATO to the East, a decision that elicited strong warnings from high-level diplomats from George Kennan, Henry Kissinger, Jack Matlock, (current CIA Director) William Burns, and many others, and led Defense Secretary William Perry to come close to resigning in protest, joined by a long list of others with eyes open. That’s of course in addition to the aggressive actions that struck directly at Russia’s concerns (Serbia, Iraq, Libya, and lesser crimes), conducted in such a way as to maximize the humiliation.

It doesn’t strain credulity to suspect that that the joint statement was a factor in inducing Putin and the narrowing circle of “hard men” around him to decide to step up their annual mobilization of forces on the Ukrainian border in an effort to gain some attention to their security concerns, in this case on to direct criminal aggression — which, indeed, we can compare with the Nazi invasion of Poland (in combination with Stalin).

We Need An Economy Without Bosses And Managers. Participatory Economics Is How.

Interest in worker cooperatives has been spreading lately across the U.S. This is largely due to growing insecurity in the face of structural changes in the workplace during the neoliberal era, which have intensified since the last financial crisis. In fact, worker cooperatives are well established in many countries of Europe, especially in France, Italy and Spain — countries with long anarchist and socialist traditions.

The movement for workers cooperatives goes beyond capitalism as it breaks down hierarchical structures and puts workers and community at the core of business operations. Yet critical questions remain about the function and impact of cooperative economics. For example, what would a post-capitalist economy where workers run productive facilities look like? How would decisions be made about production, distribution, and who earns what? And what would be the role of money under an economic system without owners or bosses? Is such an economic future even realistic, or a mere utopian dream?

Michael Albert has been advancing a vision of participatory economics for over 40 years now. In his view, “Participatory economics proposes a few key institutions that its advocates feel to be essential for an economy to fulfill quite widely held worthy aspirations including solidarity, diversity, equity, self management, and sustainability—classlessness—and to of course also be viable for producing and allocating to meet needs and develop potentials of everyone.”

Albert’s latest book, No Bosses: A New Economy for a Better World, presents a detailed pathway toward an economy based on genuine self-management and solidarity.

C.J. Polychroniou: Your new book, No Bosses: A New Economy for a Better World, advances a vision for a new economy called participatory economics (parecon). A key idea behind your vision of an alternative economic system is worker self-management. Can you outline how such an economy would function with regard to decisions about production, allocation and rewards where workers run enterprises without bosses or owners?

Michael Albert: You ask a key question: With no owners, who will decide what? Participatory economics says we should all have a say in decisions that affect us in proportion to the degree to which we are affected. Workers’ councils should therefore make workplace decisions.

But beyond being made by their involved workers, workplace decisions need to be insightful and informed. What can facilitate that?

Look around now. About 20 percent of current employees do mainly empowering tasks. About 80 percent do mainly disempowering tasks. The empowering situations of the 20 percent convey to them information, skills, access to decisions, connections with others and confidence. The rote, repetitive and generally disempowering situations of the 80 percent diminish their information, skills, access, connections and confidence. Looking down at workers below, we have empowered managers, lawyers, engineers, financial officers, and other employees I call the coordinator class. Looking up at coordinators above, we have disempowered cleaners, short-order cooks, carriers, assemblers, and other employees I call the working class.

If we reject having owners but we retain this corporate division of labor, the empowered 20 percent will consider themselves special, responsible and important. They will set agendas and make decisions. They will pursue their own interests and defend their own dominance. The disempowered 80 percent will have to obey a new boss in place of the old boss. To eliminate this class hierarchy in which 20 percent decide and 80 percent obey, all workers will need to be comparably prepared to participate in informed decision-making. Thus, participatory economics apportions tasks into jobs so the particular mix of tasks you do and the different mix I do, and indeed the mix every worker does provides to all a comparable level of empowerment.

No Bosses argues that “balanced job complexes” would not only end the coordinator/worker class division but also be productive, efficient and effective. But No Bosses also urges that we would still have a decision-related problem because beyond its workers, what occurs in a workplace also affects direct consumers of the workplace’s products as well as bystanders who may be inundated with pollutants. For self-management, direct consumers and also adjacent bystanders also need appropriate say. Moreover, if a workplace uses a particular quantity of some input to produce a desired amount of some output, other workers elsewhere can no longer use that same bit of input to produce a different output. Metals forged into bombs can’t be forged into bridges. So, everyone needs a say in what gets made, with what, by whom, for whom. A question arises: How will participatory workplaces and consumers together exercise self-managing say to arrive at properly accounted outcomes?

Nowadays, economists tell us we have no alternative. To allocate, we must use markets and/or central planning. But No Bosses reveals that while markets and central planning do a very credible job for dominant elites, for the rest of us, they diminish worker and consumer well-being, destroy ecological balance, demolish dignity, produce anti-sociality and enforce coordinator class rule.

To escape all that, participatory economics proposes that self-managing workers’ and consumers’ councils develop and refine their respective preferences through rounds of decentralized deliberation that bring production and consumption into accord.

No Bosses demonstrates how this “participatory planning” with no top and no bottom would settle on appropriate product amounts and valuations and deliver equitable incomes consistently with self-management and balanced jobs. It shows how “participatory planning” would efficiently utilize society’s productive assets to seek human fulfillment and development in light of ecological, social and personal implications. It shows how “participatory planning” would generate solidarity and not a rat race; diversity and not homogenization; dignity and not alienation; and ecological sustainability and not collective ecocide.

What would be the role of money under this new economic system? And how would a national-based “self-management” economy deal with the forces driving the global economy?

In a participatory economy, money would account. It wouldn’t accrue. People would receive income either for the duration, intensity and onerousness of their socially valued work, or because they can’t work but get a full income nonetheless. Some goods would be free, like heath care and much else, but on the consumer side, people would mostly choose from the social product the particular mix of goods and services they wish to enjoy up to their income/budget. On the producer side, workplaces would use diverse inputs to generate outputs. Participatory planning would mediate it all without competition or authoritarian command. Items would have prices to convey information that allows people to consume in accord with their income and to produce to meet needs and develop potentials without undue waste and while respecting the environment. Imagine a debit card to make purchases. Money just facilitates equitable allocation. There is no making money by having money.

If the global economy were composed of national participatory economies interacting by way of international participatory planning, the needs and desires of the populations of its many countries would drive it. But suppose some participatory economies operate in a world that is still market guided. The participatory economies would have their own domestic valuations that reflect true social costs and benefits. The rest of the world would have market valuations that reflect bargaining power. I would hope that a participatory economy would transact with other economies using whichever of the two prices would allocate the benefits of each trade in a way that would further equity rather than abet accumulation by the rich at the expense of the poor.

How would unemployment be dealt with under this new economic system, or with individuals in general who refuse to join a workers’ enterprise or execute tasks assigned to them at workplace by the collective?

In a participatory economy, the amount of available work reflects people’s desires for the output of work. Divide all the sought work among all the potential workers and everyone is employed. If in sum people seek less output, it means everyone works less, not that some work while others don’t. The planning process plus participatory economy’s remunerative norm correlates people who seek work with workplaces who seek workers. And though I have barely mentioned it, that remunerative norm — that income is for the duration, intensity and onerousness of your socially valued labor — is another defining feature critical to participatory economy being an equitable and viable vision.

As you note, work in a participatory economy would occur via workers councils. If I was to refuse to be part of any workers council, I wouldn’t work so I also wouldn’t get income for work. Similarly, if I were to violate collectively agreed, self-managed norms in my workplace — for example, if I didn’t do my tasks, or if I did them really poorly — I could lose my job. In a participatory economy, we would get income for the duration and intensity of our socially valued work. Between jobs we would retain income. We would get income only for work that is socially valued. Someone unskilled in medicine or basketball wouldn’t be able to do surgery or shoot hoops for income. No one would want such an inferior product. No associated workers council would employ someone incapable of doing worthy work. But how do workplace councils get allotted appropriate total income for their workers? In our councils, how do we each get our fair share? How do we opt to do one job and not another? How do we get items to consume? No Bosses addresses all that and much more. But for your immediate question, in a participatory economy, unemployment of people able to work would only occur temporarily when people transition from one job to another. And such unemployed workers would retain their incomes as well.

I assume you are aware of the practical challenges facing the transition to a worker-self management economy. So, what practical advice do you offer as to how we can proceed with the type of reforms needed that would create the building blocks for an economic system without bosses?

We want enlivening, equitable, self-managing participatory economics to replace moribund, impoverishing, class-ruled capitalism. This requires that we fundamentally revolutionize the defining features of a central sphere of social life. But, as you suggest, on the way to that result, we will have to win lesser changes both for their immediate benefits to deserving constituencies, and to create the conditions for ultimately winning and implementing our greater goals. Two issues centrally arise. First, what kinds of things should we seek to win as part of the process of winning a new economy? Second, how should we fight for such immediate reforms in ways that contribute to winning a new economy?

What we might win in current society is anything that betters the lot of people suffering economic ills. For example: wage increases. Dignity. Free medical care. A degree of say over work. Free internet. Changes in investment patterns. Changes in national and local budgets. Free education. Protection against ecological violations. And so on.

And how do we win such changes in current society? We create a situation in which those who have power to implement the changes do so because the risk to their power and wealth of refusing to give in is greater than the losses they will incur due to giving in.

Next, how do we fight for such changes? What words should we use? What demands should we make? What organizations should we develop? Even more, what desires should we address and arouse? Answer: We should choose among possibilities based on whether our choice enables us to win a sought reform, but also based on whether it builds a desire to fight on for more, and based on whether it strengthens our means to win more due to how we have conducted our struggle.

We fight for a higher minimum wage, but we talk about equitable incomes. We fight for dignity and improved work conditions, but we talk about self-management and build worker and consumer councils. We fight for restraints on dumping and for reduced military expenditures, but we talk about escaping market absurdity and attaining participatory planning.

Moreover, we don’t address economy alone. Entwined with the above economic path, and with equal commitment, creativity, inspiration, audacity and priority, we simultaneously develop and seek to win cultural/community, sex/gender, and political vision with all together composing a participatory society.

Copyright © Truthout. May not be reprinted without permission.

C.J. Polychroniou is a political scientist/political economist, author, and journalist who has taught and worked in numerous universities and research centers in Europe and the United States. Currently, his main research interests are in U.S. politics and the political economy of the United States, European economic integration, globalization, climate change and environmental economics, and the deconstruction of neoliberalism’s politico-economic project. He is a regular contributor to Truthout as well as a member of Truthout’s Public Intellectual Project. He has published scores of books and over 1,000 articles which have appeared in a variety of journals, magazines, newspapers and popular news websites. Many of his publications have been translated into a multitude of different languages, including Arabic, Chinese, Croatian, Dutch, French, German, Greek, Italian, Japanese, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish and Turkish. His latest books are Optimism Over Despair: Noam Chomsky On Capitalism, Empire, and Social Change (2017); Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (with Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin as primary authors, 2020); The Precipice: Neoliberalism, the Pandemic, and the Urgent Need for Radical Change (an anthology of interviews with Noam Chomsky, 2021); and Economics and the Left: Interviews with Progressive Economists (2021).

After February’s Dire IPCC Report, The Green New Deal Is More Urgent Than Ever

The ongoing war in Ukraine does not bode well for the future of peace and sustainability on planet Earth. As Noam Chomsky said in a recent interview for Truthout, “We are at a crucial point in human history. It cannot be denied. It cannot be ignored.” The latest report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), released on February 28, spells out the dire consequences of inaction to human-induced climate change. So, where do we stand in the fight against global warming? Is the Green New Deal project making inroads?

In the interview that follows, two leading climate activists — Margaret Kwateng, a national Green New Deal organizer at Grassroots Global Justice Alliance, and Ebony Twilley Martin, co-executive director of Greenpeace USA — discuss the significance of the Green New Deal project and its potential power as a transformative policy for saving the planet and creating a more fair and just social order.

C.J. Polychroniou: What would achieving the Green New Deal look like, and can it be accomplished in the next decade given the current political climate in the U.S.?

Margaret Kwateng: We are living in a moment where nearly all of our lives are being deeply impacted by the climate crisis — especially frontline communities around the world. From extreme droughts to floods, hurricanes, tornadoes and wildfires, whole communities are being devastated. The IPCC just released its latest global assessment of climate impacts that proclaimed the climate crisis is happening now, faster and more intensely than we expected. People are more aware than ever of the urgent need to stop the burning of the planet. The colliding crisis of climate change and the global pandemic has demonstrated that tragedies do not happen in a vacuum; rather, a crisis in one sector has ripple effects throughout our economy and touches on numerous parts of people’s lives. The real solutions to the climate crisis require a transformation of the extractive economy (away from fossil fuel and other resource extraction, labor exploitation and corporate profiteering) that has brought us to this breaking point.

We envision a decade of the Green New Deal because we know this scale of global crisis will require more profound change than we have seen in years. Our movements are stepping forward with a vision and a demand focused on the reorganizing of our economy to center life and well-being.

In this way, the Green New Deal is not one law or policy. The Green New Deal is a whole set of transformative policies that are able to address multiple crises at once. The THRIVE Act, which the Green New Deal Network (GNDN) worked with congressmembers to introduce in 2021, called for a $10 trillion investment to mobilize our economy and confront climate chaos, racial injustice and economic inequality. This is the floor of what is required to confront these crises, not the ceiling.

A realized Green New Deal would grow union jobs in renewables; build affordable housing and expand clean accessible public transportation; divest from brutal systems like prisons and the military; and invest in community infrastructure. The goal is not to simply regenerate the fabric of our society but to also create a national community that values the essential labor of care workers like domestic workers, home care workers and teachers; actualizes justice for communities that have long been left behind; and reduces the ripple effect when global, local or personal crises strike.

Our current conjuncture of overlapping crises — continued pandemic, climate chaos, chronic racial injustice, democracy under attack and escalating militarization — poses both turbulent terrain to pass bold visionary policies and also the ripe opportunity for intersectional solutions that address these crises together. We need to divest from the billions of dollars going to war and violent policing of our communities, and redirect investment to renewable energy, clean transportation, affordable housing and the care sector.

Our work is not to accept the intransigence of our governments and obstructionist politicians, but to shift the political landscape entirely by demanding the full scale of what we need to survive and to offer an irresistible vision of a future in which we all thrive. That is the power and potential of our movements mobilized together behind a truly transformative Green New Deal.

What was the impetus for diverse sectors of the climate justice movement, including labor, care workers, racial justice groups and Indigenous groups to come together to form the Green New Deal Network, and what role is the GNDN playing in achieving a Green New Deal?

Kwateng: While the demand for a Green New Deal and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s Green New Deal resolution have dramatically shifted the national debate on climate change policy since 2018, the vision at the heart of a Green New Deal has been around for much longer.

Many communities have been working to make Green New Deal-like shifts a reality for decades, under other banners like climate justice and a just transition. For example, when miners realized coal jobs were leaving Kentucky and community members were fed up with the contaminated water resulting from those same mines, they decided to launch Appalachia’s Bright Future, creating plans for how to move away from disease-causing, environment-degrading fossil fuel extraction to an alternative future together.

Despite this level of on-the-ground expertise, many communities on the front lines of the climate crisis have been left out of larger conversations on how to address it. The vision for the Green New Deal Network is to be an intersectional coalition that brings together workers, community groups, activists, and Black and Indigenous organizations, particularly those on the front lines of crises, in the fight for visionary climate, care, jobs and justice policies.

The work of organizations like the Indigenous Environmental Network (IEN) has pushed the scope of the Green New Deal vision beyond just switching out gas cars for electric ones and, instead, toward centering racial justice and social, economic and ecological transformation. Just last October, IEN and allies descended on the capital to say that real climate justice means both respecting Indigenous sovereignty and stopping fossil fuel extraction.

In addition, groups like the Grassroots Global Justice Alliance and Service Employees International Union are at the table to advocate for a robust and dignified care economy as a critical component of a Green New Deal. Care workers are on the front lines of the climate crisis, and they are the backbone of a sector that will need to expand as climate crises intensify.

Because there are groups ranging from the Movement for Black Lives, to the Center for Popular Democracy, to the Working Families Party at the Green New Deal Network, we are building a united front capable of creating a Green New Deal that doesn’t replicate historically exclusive policies — in leaving out communities like women and Black folks — and instead is able to tackle the multiple crises we are facing. We are generating shared policy, electing progressives and holding them accountable, and organizing to change the social and political landscape to make the kind of change where communities across the country can thrive.

What are the barriers to bring about a Green New Deal this decade, and how do we break them down?

Ebony Twilley Martin: The Green New Deal is built on the vision of a world in which all people have what they need to thrive and the boundaries of the planet are respected. One of the biggest barriers to realizing this future is the profit-driven economic system in which massive corporations and a few wealthy elites control and exploit land, communities and legislation. This system prioritizes profits over the well-being of families while also driving the continued extraction from and commodification of the Earth. As you can see in the latest IPCC report, this is drastically upsetting the balance of life on the planet.

Unity is key in breaking down this barrier. But unity is not always easy. As we look to recover from COVID-19, address the climate crisis, advance racial justice and build an economy that puts people first, corporate overlords and those who do their bidding in Congress continually try to pit these priorities against each other in an attempt to divide us. We saw this play out last year when corporations lobbied against the Build Back Better Act attempting to put climate action, health care, workers’ rights and child care on the chopping block, despite all being overwhelmingly popular with the majority of Americans. The Green New Deal Network provides a space where organizations and communities can work together across priorities to establish a unified front. We know these crises are interconnected, and to solve one, we must address them all.

Disinformation is also a huge barrier that needs to be addressed. For years, corporations have offered us a false choice between a healthy economy or a healthy planet and communities. Oil and gas companies, in particular, like to hide behind the prospect of jobs and stability to justify their destructive “business as usual.” The truth is, we have a better chance at creating millions of good-paying, stable, union jobs with renewable energy than we do with fossil fuels. Just before the pandemic struck, clean energy jobs outnumbered fossil fuel jobs nearly three to one, totaling about 3.3 million jobs and growing 70 percent faster than the economy overall. And the clean energy industry proved resilient through 2020, too: Despite the pandemic and resulting economic crisis, 2020 was a record year for solar and wind installations, as the industry continued to attract investor interest.

Another piece of disinformation is that the current system is somehow safer. The Departments of Homeland Security and Defense, as well as the National Security Council and director of national intelligence, have all issued reports stating that climate change poses a threat to national security. Financial regulators are also calling it an emerging threat to the stability of the U.S. financial system. Most alarmingly, climate change threatens the health and safety of our families. Air pollution from fossil fuels killed 8.7 million people globally in 2018 alone. Pollution from fracked-gas infrastructure has increased the risk of cancer for 1 million Black Americans. It has also contributed to 138,000 asthma attacks and 101,000 lost school days for Black children like my sons.

Making this the decade of the Green New Deal will address these threats to our health and safety by transitioning off of fossil fuels and toward renewable energy. The House Committee on Oversight and Reform recently held hearings on the fossil fuel industry’s role in spreading disinformation, and at Greenpeace USA, we filed a complaint with the Federal Trade Commission against Chevron for greenwashing. People are starting to wise up to these tactics, but both government and private companies need to take measures to stop the spread of disinformation, and those who spread it need to be held accountable.

Chomsky: Peace Talks In Ukraine “Will Get Nowhere” If US Keeps Refusing To Join

As Russia steps up its assault on Ukraine and its forces advance on Kyiv, peace talks between the two sides were scheduled to resume today for the fourth time, but have now been postponed until tomorrow. Unfortunately, some opportunities for a peace agreement have already been squandered, so it’s hard to be optimistic about when the war will end. Regardless of when or how the war ends, though, its impact is already being felt across the international security system, as the rearmament of Europe shows. The Russian invasion of Ukraine also complicates the urgent fight against the climate crisis. The war takes a heavy toll on Ukraine and on the environment, but it also gives the fossil fuel industry extra leverage among governments.

In the interview that follows, world-renowned scholar and dissident Noam Chomsky shares his insights about the prospects for peace in Ukraine and how this war may impact our efforts to combat global warming.

Noam Chomsky, who is internationally recognized as one of the most important intellectuals alive, is the author of some 150 books and the recipient of scores of highly prestigious awards, including the Sydney Peace Prize and the Kyoto Prize (Japan’s equivalent of the Nobel Prize), and of dozens of honorary doctorate degrees from the world’s most renowned universities. Chomsky is Institute Professor Emeritus at MIT and currently Laureate Professor at the University of Arizona.

C.J. Polychroniou: Noam, while a fourth round of negotiations was scheduled to take place today between Russian and Ukrainian representatives, it is now postponed until tomorrow, and it still seems unlikely that peace will be reached in Ukraine any time soon. Ukrainians don’t appear likely to surrender, and Putin seems determined to continue his invasion. In that context, what do you think of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s response to Vladimir Putin’s four core demands, which were (a) cease military action, (b) acknowledge Crimea as Russian territory, (c) amend the Ukrainian constitution to enshrine neutrality, and (d) recognize the separatist republics in eastern Ukraine?

Noam Chomsky: Before responding, I would like to stress the crucial issue that must be in the forefront of all discussions of this terrible tragedy: We must find a way to bring this war to an end before it escalates, possibly to utter devastation of Ukraine and unimaginable catastrophe beyond. The only way is a negotiated settlement. Like it or not, this must provide some kind of escape hatch for Putin, or the worst will happen. Not victory, but an escape hatch. These concerns must be uppermost in our minds.

I don’t think that Zelensky should have simply accepted Putin’s demands. I think his public response on March 7 was judicious and appropriate.

In these remarks, Zelensky recognized that joining NATO is not an option for Ukraine. He also insisted, rightly, that the opinions of people in the Donbas region, now occupied by Russia, should be a critical factor in determining some form of settlement. He is, in short, reiterating what would very likely have been a path for preventing this tragedy — though we cannot know, because the U.S. refused to try.

As has been understood for a long time, decades in fact, for Ukraine to join NATO would be rather like Mexico joining a China-run military alliance, hosting joint maneuvers with the Chinese army and maintaining weapons aimed at Washington. To insist on Mexico’s sovereign right to do so would surpass idiocy (and, fortunately, no one brings this up). Washington’s insistence on Ukraine’s sovereign right to join NATO is even worse, since it sets up an insurmountable barrier to a peaceful resolution of a crisis that is already a shocking crime and will soon become much worse unless resolved — by the negotiations that Washington refuses to join.

That’s quite apart from the comical spectacle of the posturing about sovereignty by the world’s leader in brazen contempt for the doctrine, ridiculed all over the Global South though the U.S. and the West in general maintain their impressive discipline and take the posturing seriously, or at least pretend to do so.

Zelensky’s proposals considerably narrow the gap with Putin’s demands and provide an opportunity to carry forward the diplomatic initiatives that have been undertaken by France and Germany, with limited Chinese support. Negotiations might succeed or might fail. The only way to find out is to try. Of course, negotiations will get nowhere if the U.S. persists in its adamant refusal to join, backed by the virtually united commissariat, and if the press continues to insist that the public remain in the dark by refusing even to report Zelensky’s proposals.

In fairness, I should add that on March 13, the New York Times did publish a call for diplomacy that would carry forward the “virtual summit” of France-Germany-China, while offering Putin an “offramp,” distasteful as that is. The article was written by Wang Huiyao, president of a Beijing nongovernmental think tank.

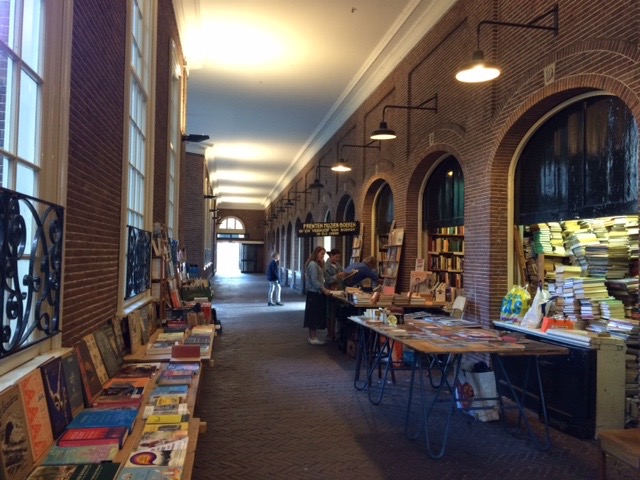

Wat kost dit boek?

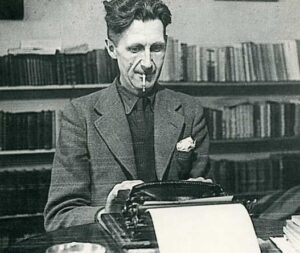

George Orwell – die toen nog gewoon Eric Blair heette, het was ver voor de verschijning van Animal Farm en 1984 – werkte in 1934 en 1935 enige tijd in een boekwinkel met tweedehands boeken, tevens buurtbibliotheek. Booklover’s Corner heette de winkel, gevestigd op de hoek van South End Green in de wijk Hampstead in Londen.

Boekverkoper had Blair een ideaal beroep geleken: je verbleef de hele dag tussen boeiende literatuur, er kwamen vast en zeker interessante klanten die je kon voorzien van deskundig advies. Het viel hem vies tegen.

Ergernissen

Niet het assortiment viel hem tegen – dat was zeker aantrekkelijk – maar vooral de klanten vormden voor hem een bron van ergernis. In zijn essay Bookshop Memories vatte hij dat ongenoegen later samen: “Many of the people who came to us were of the kind who would be a nuisance anywhere but have special opportunities in a bookshop. For example, the dear old lady who ‘wants a book for an invalid’ (a very common demand, that), and the other old lady who read such a nice book in 1897 and wonders wether you can find her a copy. Unfortunately she doesn’t remember the title or the author’s name or what the book was about, but she does remember that it had a red cover.”(1)

Daarnaast doemden vaak figuren op, net ontstegen aan de zelfkant der samenleving, die een poging deden de handelaar waardeloze boeken te verkopen, of de types die voortdurend boeken lieten reserveren, maar niet de intentie hadden deze ooit op te halen of te betalen. En dan waren er nog de klanten die gefixeerd waren op één onderwerp en voor wie de rest van geen belang leek. Echte boekenliefhebbers, -kenners of verzamelaars leken maar een klein deel van het klantenpotentieel uit te maken. Het lijkt een probleem van alle tijden. Read more

Climate Mitigation Isn’t Just A Matter Of Ethics; It’s Life And Death

The climate crisis worsens with each passing year — and even the current levels of warming are disastrous, affecting ecosystems as well as social and environmental conditions of health. People in the world’s poorest countries remain most vulnerable to the crisis. The world’s governments are slow to react to the greatest challenge facing humanity today, even though potential solutions are not in short supply, with the transition to a green economy offering the most effective pathway to tackling the problem of global warming at its roots.

There are, in addition, intermediate steps that can be taken toward climate stabilization, such as carbon pricing and even the adoption of a universal basic income scheme as a means to counter the effects of global warming. Meanwhile, policy frameworks for climate adaptation are urgently needed, as renowned economist James K. Boyce points out in this interview. Boyce is professor emeritus of economics and senior fellow at the Political Economy Research Institute of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. He received his PhD in economics from Oxford University and is the author of scores of books, including, most recently, The Case for Carbon Dividends (2019) and Economics for People and the Planet (2021). He received the 2017 Leontief Prize for Advancing the Frontiers of Economic Thought.

C.J. Polychroniou: The climate crisis is the biggest problem facing humanity in the 21st century. In the effort to avoid a greenhouse apocalypse, competing approaches to climate action have been advanced, ranging from outright technological solutions to an economic and social revolution as envisioned in the Green New Deal project and everything in between. Two of those “in between” approaches for cutting carbon emissions are cap-and-trade, a system already implemented in the state of California, and carbon pricing and carbon dividends, which is the approach you are advocating. Why do we need to put a price on carbon? How does carbon pricing work, and what are its benefits?

James K. Boyce: First, let me say that I do not think it is useful to invoke the language of a coming “apocalypse.” It’s a vision with a lot of historical baggage, much of it downright reactionary, as my partner Betsy Hartmann explains in her book, The America Syndrome: War, Apocalypse, and Our Call to Greatness (Seven Stories Press, 2019). It misrepresents the climate crisis as a cliff edge, an all-or-nothing question akin to nuclear war, as opposed to an unfolding process that has ever-worsening consequences for humans and other living things. And it can instill a sense of despair and hopelessness that is deeply counterproductive. I agree with the late Raymond Williams that the task of the true radical is “to make hope possible, not despair convincing.”

Something similar can be said about the contrast between technological fixes and revolutionary transformations. Economic and social revolution is a process, too, not a one-off affair. Technological change can help to propel institutional change, and vice versa, and often there is an intimate connection between the two. I do not think we will solve the climate crisis with new technologies alone. The transition to a clean energy economy will require profound changes not only in how we relate to the natural world but also in how we relate to each other. I have argued that it will require a narrowing of inequalities and a deepening of democracy. But it would be folly to sit aside, waiting for social and economic revolution, before tackling the climate problem.

Cap-and-trade and carbon dividend policies both put a price on carbon. Instead of being able to dump carbon into the atmosphere free of charge (more precisely, free of monetary charge, since nature is charging us big time), pollution would carry a price tag. But there are crucial differences between these two policies. Cap-and-trade gives free pollution permits to corporations, up to the limit set by the cap. Consumers feel the bite in higher prices for transportation fuels, heating and electricity, just as they do when the oil cartel restricts supplies. The extra money they pay goes as windfall profits into the coffers of the corporations that received free permits. This may blunt political opposition to a carbon price from fossil fuel lobbyists, but their first preference remains no cap at all, as was shown in the repeat debacles of efforts to pass cap-and-trade bills in Washington, D.C. in the first decade of the century.

Carbon dividend policies put a price on carbon, too, either via a cap with auctioned (not free) permits or by means of a tax. But instead of fueling windfall profits, the money from higher prices goes directly back to the public in equal per-person payments, consistent with the principle that we all own the gifts of nature — in this case, the limited capacity of the biosphere to absorb carbon emissions — in common and equal measure. As I discuss in my book, The Case for Carbon Dividends (Polity Press, 2019), this is an example of universal property. The right to receive carbon dividends cannot be bought or sold, or accumulated in a few hands, or owned by corporations. Universal property is individual, inalienable and perfectly egalitarian. This new kind of property, which is more akin to traditional common property than to private property or state property, could be a cornerstone for what is sometimes called “libertarian socialism.”

It’s not that we simply need to put a price — any price — on carbon, although anything is better than the prevailing de facto price of zero. What we need to do is to keep the fossil fuels in the ground, to curtail their extraction at a pace and scale ambitious enough to stabilize the Earth’s climate by the middle of the century. This is the goal of the Paris Agreement. In practice, it means that high-consuming countries, like the United States, must cut their use of fossil fuels by about 8 or 9 percent per year, year after year, between now and 2050. The easiest way to arrive at the “right” price on carbon is to cap the amount of fossil fuels we allow to enter our economy to meet this trajectory. For each ton of carbon they sell, fossil fuel firms would have to surrender a permit. They would buy permits (up to the limit set by the cap that tightens over time) at auctions. This is not rocket science. Quarterly auctions have been held since 2009 under the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative for power plants in the northeastern states of the U.S. The carbon price comes about as a side effect of keeping fossil fuels in the ground, not as an end in itself.

n addition to climate stabilization, a side benefit of carbon dividends is that they would take a modest step toward reducing economic inequality, which has reached obscene levels in the U.S. and many other countries. Most households would come out ahead financially with carbon dividends, receiving more in dividends than they pay in higher fuel prices, for the simple reason that their carbon footprints are smaller than average. High-income households with their outsized consumption of carbon, and everything else, would pay more than they get back, but they can afford it.

You have also argued for a universal basic income as a solution to inequality and the effects of global warming. How would a universal income be funded, and would it be an addition to existing welfare programs or a replacement for them?

Correction: Universal basic income can be part of the solution. Guaranteed employment can also be part of the solution, and as my colleagues Bob Pollin and his coauthors have shown, the clean energy transition will generate millions of jobs. The extent to which existing welfare programs become redundant would depend on how much money we’re talking about. A big advantage of universal income, compared to means-tested welfare payments, is that it unites society rather than dividing it between the welfare-eligible poor and everyone else. Universality helps to ensure political durability, as we’ve seen with Social Security and Medicare here in the U.S.

For universal basic income, a key question is how to pay for it. Most proposals rely on government funding. But redistributive taxation can be a heavy lift, and its durability is never certain since it depends on the vagaries of party politics. This is one reason I favor universal property as a source of universal basic income [universal property refers to the idea of a universal birthright to an equal share of co-inherited wealth]. Carbon dividends are one example. In his new book, Ours: The Case for Universal Property (Polity Press, 2021), Peter Barnes discusses a number of other possibilities.

We now know that dramatic mass climate catastrophe is inevitable, especially for mega-cities and coastal populations. What are the sorts of changes (involving migration, changes in how cities are structured, changes in how nations relate to each other, technologies, etc.) that could help humans as a global community weather these catastrophes without massive human deaths? And what are the sorts of pressures and dynamics (protests, legislation, international cooperation) that would actually make these changes imaginable to implement in time?

Every year that passes without serious policies to keep fossil carbon in the ground, where it belongs, increases the suffering that climate change will inflict. Coastal populations will be among the most seriously affected, but they will not be alone. Drought-prone regions in Africa, for example, are at grave risk, too.

Not long ago, proponents of action to halt climate change (“mitigation” in the official lingo), including many governments in the Global South, were averse to discussing adaptation, fearing that it would let the big polluters off the mitigation hook. Times have changed. Today, the need for adaptation is urgent and undeniable. The key questions are how adaptation resources will be allocated across and within countries, and who will foot the bill.