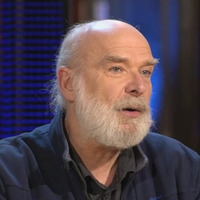

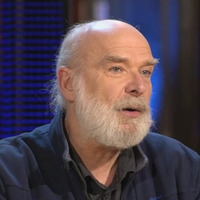

Robert Pollin

The Green New Deal is the boldest and most likely the most effective way to combat the climate emergency. According to its advocates, the Green New Deal will save the planet while boosting economic growth and generating in the process millions of new and well-paying jobs. However, a growing number of ecological economists contend that rescuing the environment necessitates “degrowth.”

To the extent that a sharp reduction in economic activity is a positive goal, “degrowth” requires overturning the current world order. But do we have the luxury to wait for a new world order while the catastrophic impacts of global warming are already upon us and getting worse with each passing decade?

World-renowned progressive economist Robert Pollin, distinguished professor of economics and co-director of the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, is one of the leading proponents of a global Green New Deal. In this interview, he addresses the degrowth vs. Green New Deal debate, looking at how economies can grow while still advancing a viable climate stabilization project as long as the growth process is absolutely decoupled from fossil fuel consumption.

C.J. Polychroniou: Since the idea of a Green New Deal entered into public consciousness, the debate about climate emergency is becoming increasingly polarized between those advocating “green growth” and those arguing in support of “degrowth.” What exactly does “degrowth” mean, and is this at the end of the day an economic or an ideological debate?

Robert Pollin: Let me first say that I don’t think that the debate on the climate emergency between advocates of degrowth versus the Green New Deal is becoming increasingly polarized, certainly not as a broad generalization. Rather, as an advocate of the Green New Deal and critic of degrowth, I would still say that there are large areas of agreement along with some significant differences. For example, I agree that uncontrolled economic growth produces serious environmental damage along with increases in the supply of goods and services that households, businesses and governments consume. I also agree that a significant share of what is produced and consumed in the current global capitalist economy is wasteful, especially much, if not most, of what high-income people throughout the world consume. It is also obvious that growth per se as an economic category makes no reference to the distribution of the costs and benefits of an expanding economy. I think it is good to keep in mind both the areas of agreement as well as the differences.

But what about definitions: What do we actually mean by the Green New Deal and degrowth?

Starting with the Green New Deal: The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimates that for the global economy to move onto a viable climate stabilization path, global emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) will have to fall by about 45 percent as of 2030 and reach net zero emissions by 2050. As such, by my definition, the core of the global Green New Deal is to advance a global project to hit these IPCC targets, and to accomplish this in a way that also expands decent job opportunities and raises mass living standards for working people and the poor throughout the world. The single most important project within the Green New Deal entails phasing out the consumption of oil, coal and natural gas to produce energy, since burning fossil fuels is responsible for about 70 – 75 percent of all global CO2 emissions. We then have to build an entirely new global energy infrastructure, the centerpieces of which are high efficiency and clean renewable energy sources — primarily solar and wind power. The investments required to dramatically increase energy efficiency standards and to equally dramatically expand the global supply of clean energy sources will also be a huge source of new job creation, in all regions of the world. These are the basics of the Green New Deal as I see it. It is that simple in concept, while also providing specific pathways for achieving its overarching goals.

Now on degrowth: Since I am not a supporter, it would be unfair for me to be the one explaining what it means. So here is how some of the leading degrowth proponents themselves describe the concept and movement. For example, in a 2015 edited volume titled, Degrowth: A Vocabulary for a New Era, the volume’s editors Giacomo D’Alisa, Federico Demaria and Giorgos Kallis write that, “The foundational theses of degrowth are that growth is uneconomic and unjust, that it is ecologically unsustainable and that it will never be enough.” More recently, a 2021 paper by Riccardo Mastini, Giorgos Kallis and Jason Hickel, titled, “A Green New Deal without Growth?,” write that “ecological economists have defined degrowth as an equitable downscaling of throughput, with a concomitant securing of wellbeing.”

It is instructive here that, in this 2021 paper, Mastini, Kallis and Hickel do also acknowledge that degrowth has not advanced into developing a specific set of economic programs, writing that “degrowth is not a political platform, but rather an ‘umbrella concept’ that brings together a wide variety of ideas and social struggles.” This acknowledgement reflects, in my view, a major ongoing weakness with the degrowth literature, which is that, in concerning itself primarily with very broad themes, it actually gives almost no detailed attention to developing an effective climate stabilization project, or any other specific ecological project. Indeed, this deficiency was reflected in a 2017 interview with the leading ecological economist Herman Daly himself, without question a major intellectual progenitor of the degrowth movement. Daly says in the interview that he is “favorably inclined” toward degrowth, but nevertheless demurs that he is “still waiting for them to get beyond the slogan and develop something a little more concrete.”

Read more

CJ Polychroniou

The progressive forces fighting for a democratic future have a truly herculean task ahead of them.

It is no longer an unknown fact or a view propounded by a handful of radical historians and political scientists: the American political system has such severe structural flaws that it is potentially antithetical to democracy and surely detrimental to the promotion of the common good.

Consider the following stark realizations about the condition of American democracy as evidence of the changing times:

The United States has been rated for a number of consecutive years by the Economist Intelligence Union as a “flawed democracy.”

Scores of highly respected mainstream scholars have analyzed massive amounts of data showing that public opinion counts very little in US policymaking (see, for example, Larry Bartels, Unequal Democracy: The Political Economy of the New Gilded Age; Princeton University Press, 2nd ed., 2016) to conclude that the American political system works essentially in a manner that actually subverts the will of the common people.

Others, like Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz, have argued that, because of rules set in the political system, the American economy is rigged to favor the rich, a view that is obviously wholeheartedly endorsed by Kishore Mahbubani, Distinguished Fellow from Asia Research Institute, at the National University of Singapore, when he declares that the US functions like a democracy but is actually a plutocracy.

And Timothy K. Kuhner, Professor of Law at the University of Auckland, has gone even further by arguing most convincingly in King’s Law Journal that the United States isn’t only a plutocracy, but the only plutocracy in the world to be established by law.

To a large extent, of course, the structural flaws in the American political system have their origins in the many anti-democratic elements found in the Constitution. This is the view of eminent constitutional scholars such Erwin Chemerinsky, Dean and Distinguished Professor of Law at Berkeley Law School, and Sanford Levinson, W. St. John Garwood and W. St. John Garwood, Jr. Centennial Chair in Law at the University of Texas Law School, and author of Our Undemocratic Constitution (Oxford University Press, 2006).

Let’s start with one of the basic principles of democracy which is “one person, one vote.” It is not applicable to the case of American “democracy” where US presidents are chosen by electors, not by popular vote. Hence the “democratic” anomaly of a candidate elected to become the 45th president of the United States after having lost the popular vote by a bigger margin than any other US president. Indeed, Donald Trump was elected president by trailing Hillary Clinton by nearly three million votes.The same thing happened in 2000, when Al Gore won nearly half a million more votes than George W. Bush, but it was Bush who won the presidency by being declared winner in the state of Florida by less than 540 votes.

In any other modern democratic system, such electoral outcomes would be imaginable only if democracy was crushed by some kind of a military coup with the aim of installing in power the “preferred” candidate of the ruling class.

To be sure, there is nothing in the Constitution that grants American voters the right to choose their president. When American voters go to the polls to vote for a presidential candidate, what they are essentially doing is casting a vote for their preferred party’s nominated slate of electors.

The electoral college system is democracy’s ugliest anachronism. It was designed by the founding fathers in order to prevent the masses from choosing directly who will run the country, and it’s simply shocking that it still exists more than two hundred years later.

Read more

Noam Chomsky

Today’s Republican Party is an extremist force that no longer qualifies as a mainstream political party and is surely not interested in participating in “normal” politics. In fact, today’s GOP is so wrapped around extreme and irrational beliefs that even Europe’s far-right parties and movements, including Marine Le Pen’s National Rally, seem conventional in comparison.

The GOP’s political identity has been dramatically shaped by former President Donald Trump, but these recent shifts would not have been possible if there weren’t already an array of groups across U.S. society and culture (including white supremacists, right-wing Evangelical Christians and Second Amendment activists, to name just a few) that have long embraced extremist and “proto-fascist” views about the way the country should be governed and the values that it should hold. For them, Trump was and remains America’s “great white hope.” In this context, Trump’s voting base — which continues to believe in the idea of a stolen election and to support Trump-led GOP efforts to stamp critical race theory out of schools and restrict voting rights — speaks volumes about the anti-democratic and threatening nature of today’s GOP.

In the interview that follows, world-renowned scholar and activist Noam Chomsky explains what has happened to the Republican Party and why even more than democracy is at stake if the “proto-fascist” forces inspired by Trump return to power.

C.J. Polychroniou: Over the course of the past few decades, the Republican Party has gone through a series of ideological transformations — from traditional conservatism to reactionism and finally to what we may define as “proto-fascism” where the irrational has become the driving force. How do we explain what has happened to the GOP?

Noam Chomsky: Your term “neoliberal proto-fascism” seems to me quite an accurate characterization of the current Republican organization — I’m hesitant to call them a “Party” because that might suggest that they have some interest in participating honestly in normal parliamentary politics. More fitting, I think, is the judgment of American Enterprise Institute political analysts Thomas Mann and Norman Ornstein that the modern Republican Party has transformed to a “radical insurgency” with disdain for democratic participation. That was before the Trump-McConnell hammer blows of the past few years, which drove the conclusion home more forcefully.

The term “neoliberal proto-fascism” captures well both the features of the current party and the distinction from the fascism of the past. The commitment to the most brutal form of neoliberalism is apparent in the legislative record, crucially the subordination of the party to private capital, the inverse of classic fascism. But the fascist symptoms are there, including extreme racism, violence, worship of the leader (sent by God, according to former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo), immersion in a world of “alternative facts” and a frenzy of irrationality. Also in other ways, such as the extraordinary efforts in Republican-run states to suppress teaching in schools that doesn’t conform to their white supremacist doctrines. Legislation is being enacted to ban instruction in “critical race theory,” the new demon, replacing Communism and Islamic terror as the plague of the modern age. “Critical race theory” is the scare-phrase used for the study of the systematic structural and cultural factors in the hideous 400-year history of slavery and enduring racist repression. Proper indoctrination in schools and universities must ban this heresy. What actually happened for 400 years and is very much alive today must be presented to students as a deviation from the real America, pure and innocent, much as in well-run totalitarian states.

What’s missing from “proto-fascism” is the ideology: state control of the social order, including the business classes, and party control of the state with the maximal leader in charge. That could change. German industry and finance at first thought they could use the Nazis as their instrument in beating down labor and the left while remaining in charge. They learned otherwise. The current split between the more traditional corporate leadership and the Trump-led party is suggestive of something similar, but only remotely. We are far from the conditions that led to Mussolini, Hitler, and their cohorts.

On the driving force of irrationality, the facts are inescapable and should be of deep concern. Though we can’t credit Trump entirely with the achievement, he certainly has shown great skill in carrying out a challenging assignment: implementing policies for the benefit of his primary constituency of great wealth and corporate power while conning the victims into worshipping him as their savior. That’s no mean achievement, and inducing an atmosphere of utter irrationality has been a primary instrument, a virtual prerequisite.

We should distinguish the voting base, now pretty much owned by Trump, from the political echelon (Congress) — and distinguish both from a more shadowy elite that really runs the Party, McConnell and associates.

Read more

- door: Robert-Henk Zuidinga

Er is een tijd geweest, lang vóór de Ryam- en de Beyoncé-agenda de klassen vrolijk kleurden, dat de agenda voor het nieuwe schooljaar door de school zelf werd verstrekt. Andere modellen waren uit den boze. Het waren dan ook saaie, grijzige notitieboekjes, zonder opsmuk.

Er is een tijd geweest, lang vóór de Ryam- en de Beyoncé-agenda de klassen vrolijk kleurden, dat de agenda voor het nieuwe schooljaar door de school zelf werd verstrekt. Andere modellen waren uit den boze. Het waren dan ook saaie, grijzige notitieboekjes, zonder opsmuk.

De enige frivoliteit die de ontwerpers zich veroorloofden, waren korte, lichtvoetige versjes, gewoonlijk rechtsonder op de zaterdag. Populair waren bijvoorbeeld C. Buddingh’, Daan Zonderland en Kees Stip; volwassenen kunnen dankzij die saaie agenda’s vaak nog klassieke regels uit het hoofd reciteren als

Ik ben de blauwbilgorgel,

Mijn vader was een porgel,

Mijn moeder was een porulan

van Buddingh’, of

Er zijn hier heel wat maden bij

die made zijn in Germanij

van Kees Stip, in de gedaante van Trijntje Fop.

Favoriet waren de rijmpjes van John O’Mill, het pseudoniem van de Brabantse docent Engels Jan van der Meulen (1915-2005). Ze waren grappig, eenvoudig te onthouden en dus altijd makkelijk te citeren. Een voorbeeld:

Rot young

A terrible infant, called Peter

sprinkled his bed with a gheter.

His father got woost,

took hold of a cnoost

and gave him a pack on his meter.

Of

Drents adrift

A hot headed Drent in Ter Apel

who always ran too hard from staple

forsplintered his plate

when the waitress was late

and gave her a lell with the laple.

Ze verschenen, behalve in die sombere agenda’s, in kleine boekjes met olijke titels als Lyrical Laria of Rollicky Rhymes, Bonny Ballads, an O’Mill medley of Verse & Worse, Curious Couplets, in Waals en Koeterwaals of – de mooiste – Popsy Poems. Pre-Popsylated Poetry. Rispe Rijmen in Dutch and double Dutch.

Ze verschenen, behalve in die sombere agenda’s, in kleine boekjes met olijke titels als Lyrical Laria of Rollicky Rhymes, Bonny Ballads, an O’Mill medley of Verse & Worse, Curious Couplets, in Waals en Koeterwaals of – de mooiste – Popsy Poems. Pre-Popsylated Poetry. Rispe Rijmen in Dutch and double Dutch.

(Korte taalles: double Dutch is Engels voor “onzin uitkramen”. Risp komt niet voor in het Nederlands en lijkt vooral door de dichter gekozen vanwege de mooie alliteratie met “rijmen”.

Pre-Popsylated wordt in een inleiding door de dichter zelf als volgt toegelicht: “All the verse in this bundle has been carefully and critically pre-popsylated by the author himself, so that any resemblance to art or poetry is purely accidental”. Het zal geen verbazing wekken, dat popsylated niet in de Engelse woordenschat voorkomt. Met wat goede wil kan nog gedacht worden aan een woordspeling met preposterous, volgens het woordenboek te vertalen met “ongerijmd”.)

Read more

Éric Toussaint – Photo: cadtm.org

Massive debt levels are a feature of contemporary capitalism that cannot be eradicated without radical change, says political scientist Éric Toussaint.

“The indebtedness of the working classes is directly connected to the widening poverty gap and increasing inequality, and to the demolition of the welfare state that most governments have been working at since the 1980s,” says Toussaint in this exclusive interview for Truthout.

Toussaint — a historian and international spokesperson for the Committee for the Abolition of Illegitimate Debt (CADTM), and author of several books on debt, development and globalization — shares his thoughts on debt, inequality and contemporary socialist movements in the conversation that follows.

C.J. Polychroniou: Over the past few decades, inequality is rising in many countries around the world, both across the Global North and the Global South, creating what UN Chief António Guterres called in his foreword to the World Social Report 2020 “a deeply unequal global landscape.” Moreover, the top 1 percent of the population are the big winners in the globalized capitalist economy of the 21st century. Is inequality an inevitable development in the face of globalization, or the outcome of politics and policies at the level of individual countries?

Éric Toussaint: Rising inequality is not inevitable. Nevertheless, it is obvious that the explosion of inequality is consubstantial with the phase that the world capitalist system entered into in the 1970s. The evolution of inequality in the capitalist system is directly related to the balance of power between the fundamental social classes, between capital and labor. When I use the term “labor,” that means urban wage-earners as well as rural workers and small-scale farming producers.

The evolution of capitalism can be divided into broad periods according to the evolution of inequality and the social balance of power. Inequality increased between the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in the first half of the 19th century and the policies implemented by the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States in the 1930s, and then decreased up to the early 1980s. In Europe, the turn towards lower inequality lagged 10 years behind the United States. It was not until the end of World War II and the final defeat of Nazism that inequality-reducing policies were put in place, whether in Western Europe or Moscow-led Eastern Europe. In the major economies of Latin America, there was a reduction in inequality from the 1930s to the 1970s, notably during the presidencies of Lázaro Cárdenas in Mexico and Juan D. Perón in Argentina. In the period from the 1930s to the 1970s, there were massive social struggles. In many capitalist countries, capital had to make concessions to labor in order to stabilize the system. In some cases, the radical nature of social struggles led to revolutions, as in China in 1949 and Cuba in 1959.

The return to policies that strongly aggravated inequality began in the 1970s in Latin America and part of Asia. From 1973 onward, the dictatorship of Gen. Augusto Pinochet (advised by the “Chicago Boys,” the Chilean economists who had studied laissez-faire economics at the University of Chicago with Milton Friedman), the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos in the Philippines, and the dictatorships in Argentina and Uruguay are just a few examples of countries where neoliberal policies were first put into practice.

These neoliberal policies, which produced a sharp increase in inequality, became widespread from 1979 in Great Britain under Margaret Thatcher, from 1980 in the United States under the Reagan administration, from 1982 in Germany under the Kohl government, and in 1982-1983 in France after François Mitterrand’s turn to the right.

Inequality increased sharply with the capitalist restoration in the countries of the former Soviet bloc in Central and Eastern Europe. In China from the second half of the 1980s onward, the policies dictated by Deng Xiaoping also led to a gradual restoration of capitalism and a rise in inequality.

It is also quite clear that for the ideologues of the capitalist system and for many international organizations, a rise in inequality is a necessary condition for economic growth.

It should be noted that the World Bank does not consider a rising level of inequality as negative. Indeed, it adopts the theory developed in the 1950s by the economist Simon Kuznets, according to which a country whose economy takes off and progresses must necessarily go through a phase of increasing inequality. According to this dogma, inequality will start to fall as soon as the country has reached a higher threshold of development. It is a version of pie in the sky used by the ruling classes to placate the oppressed on whom they impose a life of suffering.

Read more

Richard Falk

After four elections in less than two years, Benjamin Netanyahu’s record 12-year rule comes officially to an end on Sunday.

The government to replace him consists of a coalition of eight parties from across Israel’s political spectrum and will be led by the ultranationalist Naftali Bennett who will serve for the first two years.

Indeed, indicative of the direction of Israeli politics and society over the course of the last 15 years or so, the end of the corrupt and much-maligned Netanyahu reign may be no reason for celebration, as it will be replaced not simply by a coalition government built around numerous structural contradictions, but by one that may potentially prove to be far more reactionary and dangerous.

The situation is grave for Palestinians, who only a few weeks ago experienced under Netanyahu’s orders yet another massive assault on Gaza, which ended in the death of more than 200 people including dozens of children, and widespread damage to the enclave’s infrastructure. The person to replace Netanyahu as prime minister is a religious extremist who has been a vocal advocate of Israeli settlements and a fervent opponent of a Palestinian state.

The dawn of the new era in Israeli politics starts with the latest cycle of violence against the Palestinians, which seems to have been directly related to the reality of domestic Israeli politics in general and the policy of ethnic cleansing in particular. This is the view of Richard Falk, one of the world’s most insightful and cited scholars of international affairs over the course of the last half century, as made clear in the exclusive interview below for Truthout. Falk is professor emeritus of International Law at Princeton University, Chair of Global Law at Queen Mary University of London, former United Nations Human Rights Rapporteur on human rights in the Palestinian territories, and author of more than fifty books and thousands of essays in global politics and international law.

C.J. Polychroniou: Richard, the latest Israeli attack, which caused massive destruction in the Gaza Strip, ended with a ceasefire after growing U.S. and international pressure after 11 days. In your view, what factors or parties reignited the violence?

Richard Falk: This latest upsurge of violence in the relations between Israel and Palestine seems to arise from a combination of circumstances…. It is clear that Israel’s usual claim of a right to defend itself is far from the whole story, especially when its behavior seemed designed to provoke Hamas to act in response. In light of this, we should investigate why Israel wanted to launch a major military operation against Gaza at this time when the situation seemed quiet.

The easiest answer to the question — to save Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s skin. It seems that the precarious political position and legal vulnerability of the Israeli leader, is the best back story, but far from a complete picture. It helps account for the seemingly reckless Israeli provocations that preceded the flurry of rockets from Hamas and affiliates. Netanyahu had failed three times to form a government and was facing an opposition coalition that was effectively poised to displace him as leader. If displaced as prime minister, Netanyahu would have to face substantial criminal charges for fraud, bribery and breach of public trust in Israeli courts, which could result in a jail sentence.

Why would a wily leader and ardent nationalist play roulette with the well-being of Israel? The answer seems to involve the character of the man rather than an astute policy calculation…. To the extent the Netanyahu approach was knowledge-based, it reflected the reasonable belief that Israelis put aside differences and give their total allegiance to the head of state during a wartime interlude. Netanyahu had every reason to believe that in this situation, as so often in the past, Israelis would rally around the flag, and be thankful for his leadership in a security crisis.

There is no doubt that Israeli behavior preceding the rockets was so inflammatory that we must assume it was intended to be highly provocative. First came high-profile evictions of six Palestinian families from their Sheikh Jarrah homes on flimsy legal grounds, with a prospect of more evictions to follow. These court rulings enraged the Palestinians. It reinforced their sense of continuing victimization taking the form of insecurity as to Palestinian residence rights in East Jerusalem, perceived as ethnic cleansing. This reawakened the memories of the 700,000 or more Palestinians who fled or were forced across the borders of what became Israel to Jordan, Lebanon, Gaza and the West Bank (until 1967 under Jordanian administration) in the 1948 War, becoming refugees, and never thereafter allowed to return to their homes or homeland, which was and is their right under international law.

This process of coercive demographic rebalancing was integral to the essential racial and idealistic character of the Zionist movement, which sought to establish not only a Jewish state but a democracy that could qualify for political legitimacy by Western criteria. To achieve this goal, however, depended on implementing policies ensuring and maintaining a secure Jewish-majority population, [policies] which were themselves denial of fundamental human rights. These controversial Sheikh Jarrah evictions were continuing this Judaizing of East Jerusalem after more than 70 years since Israel was founded. In other words, what Israeli Jews treated as a demographic imperative that was almost synonymous with maintaining a Jewish state for the Palestinians had the character of a continuous process of ethnic cleansing, which meant second-class citizenship and living with perpetual insecurity.

Read more