Noam Chomsky ~ Photo: en.wikipedia.org

For the prelude to this interview, read yesterday’s conversation with Noam Chomsky on “Trump and the Flawed Nature of US Democracy“, which exposes the pitfalls of the political system that made Trump’s rise to power a reality.

Are Donald Trump’s selections for his cabinet and other top administration positions indicative of a man who is ready to “drain the swamp?” Is the president-elect bent on putting China on the defensive? What does he have in mind for the Middle East? And why did Barack Obama choose at this juncture — that is, toward the end of his presidency — to have the US abstain from a UN resolution condemning Israeli settlements? Are new trends and tendencies in the world order emerging? In this exclusive Truthout interview, Noam Chomsky addresses these critical questions just two weeks before the White House receives its new occupant.

C.J. Polychroniou: Noam, the president-elect’s cabinet is being filled by financial and corporate bigwigs and military leaders. Such selections hardly reconcile with Trump’s pre-election promises to “drain the swamp,” so what should we expect from this megalomaniac and phony populist insofar as the future of the Washington establishment is concerned?

Noam Chomsky: In this respect — note the qualification — Time magazine put it fairly well (in a Dec. 26 column by Joe Klein): “While some supporters may balk, Trump’s decision to embrace those who have wallowed in the Washington muck has spread a sense of relief among the capital’s political class. ‘It shows,’ says one GOP consultant close to the President-elect’s transition, ‘that he’s going to govern like a normal Republican’.”

There surely is some truth to this. Business and investors plainly think so. The stock market boomed right after the election, led by the financial companies that Trump denounced during his campaign, particularly the leading demon of his rhetoric, Goldman Sachs. According to Bloomberg News, “The firm’s surging stock price,” up 30 percent in the month after the election, “has been the largest driver behind the Dow Jones Industrial Average’s climb toward 20,000.” The stellar market performance of Goldman Sachs is based largely on Trump’s reliance on the demon to run the economy, buttressed by the promised roll-back in regulations, setting the stage for the next financial crisis (and taxpayer bailout). Other big gainers are energy corporations, health insurers and construction firms, all expecting huge profits from the administration’s announced plans. These include a Paul Ryan-style fiscal program of tax cuts for the rich and corporations, increased military spending, turning the health system over even more to insurance companies with predictable consequences, taxpayer largesse for a privatized form of credit-based infrastructure development, and other “normal Republican” gifts to wealth and privilege at taxpayer expense. Rather plausibly, economist Larry Summers describes the fiscal program as “the most misguided set of tax changes in US history [which] will massively favor the top 1 per cent of income earners, threaten an explosive rise in federal debt, complicate the tax code and do little if anything to spur growth.”

But, great news for those who matter.

There are, however, some losers in the corporate system. Since November 8, gun sales, which more than doubled under Obama, have been dropping sharply, perhaps because of lessened fears that the government will take away the assault rifles and other armaments we need to protect ourselves from the Feds. Sales rose through the year as polls showed Clinton in the lead, but after the election, the Financial Times reported, “shares in gun makers such as Smith & Wesson and Sturm Ruger plunged.” By mid-December, “the two companies had fallen 24 per cent and 17 per cent since the election, respectively.” But all is not lost for the industry. As a spokesman explains, “To put it in perspective, US consumer sales of firearms are greater than the rest of the world combined. It’s a pretty big market.”

Normal Republicans cheer Trump’s choice for Office of Management and Budget, Mick Mulvaney, one of the most extreme fiscal hawks, though a problem does arise. How will a fiscal hawk manage a budget designed to massively escalate the deficit? In a post-fact world, maybe that doesn’t matter.

Also cheering to “normal Republicans” is the choice of the radically anti-labor Andy Puzder for secretary of labor, though here too a contradiction may lurk in the background. As the ultrarich CEO of restaurant chains, he relies on the most easily exploited non-union labor for the dirty work, typically immigrants, which doesn’t comport well with the plans to deport them en masse. The same problem arises for the infrastructure programs; the private firms that are set to profit from these initiatives rely heavily on the same labor source, though perhaps that problem can be finessed by redesigning the “beautiful wall” so that it will only keep out Muslims.

Read more

Noam Chomsky

Trump’s presidential victory exposed to the whole world the flawed nature of the US model of democracy. Beginning January 20, both the country and the world will have to face a political leader with copious conflicts of interest who considers his unpredictable and destructive style to be a leadership asset. In this exclusive interview for Truthout, world-renowned public intellectual Noam Chomsky sheds light on the type of democratic model the US has designed and elaborates on the political import of Trump’s victory for the two major parties, as this new political era begins.

C.J. Polychroniou: Noam, I want to start by asking you to reflect on the following: Trump won the presidential election even though he lost the popular vote. In this context, if “one person, one vote” is a fundamental principle behind every legitimate model of democracy, what type of democracy prevails in the US, and what will it take to undo the anachronism of the Electoral College?

Noam Chomsky: The Electoral College was originally supposed to be a deliberative body drawn from educated and privileged elites. It would not necessarily respond to public opinion, which was not highly regarded by the founders, to put it mildly. “The mass of people … seldom judge or determine right,” as Alexander Hamilton put it during the framing of the Constitution, expressing a common elite view. Furthermore, the infamous 3/5th clause ensured the slave states an extra boost, a very significant issue considering their prominent role in the political and economic institutions. As the party system took shape in the 19th century, the Electoral College became a mirror of the state votes, which can give a result quite different from the popular vote because of the first-past-the-post rule — as it did once again in this election. Eliminating the Electoral College would be a good idea, but it’s virtually impossible as the political system is now constituted. It is only one of many factors that contribute to the regressive character of the [US] political system, which, as Seth Ackerman observes in an interesting article in Jacobin magazine, would not pass muster by European standards.

Ackerman focuses on one severe flaw in the US system: the dominance of organizations that are not genuine political parties with public participation but rather elite-run candidate-selection institutions often described, not unrealistically, as the two factions of the single business party that dominates the political system. They have protected themselves from competition by many devices that bar genuine political parties that grow out of free association of participants, as would be the case in a properly functioning democracy. Beyond that there is the overwhelming role of concentrated private and corporate wealth, not just in the presidential campaigns, as has been well documented, particularly by Thomas Ferguson, but also in Congress.

A recent study by Ferguson, Paul Jorgensen and Jie Chen on “How Money Drives US Congressional Elections,” reveals a remarkably close correlation between campaign expenditures and electoral outcomes in Congress over decades. And extensive work in academic political science — particularly by Martin Gilens, Benjamin Page and Larry Bartlett — reveals that most of the population is effectively unrepresented, in that their attitudes and opinions have little or no effect on decisions of the people they vote for, which are pretty much determined by the very top of the income-wealth scale. In the light of such factors as these, the defects of the Electoral College, while real, are of lesser significance.

Read more

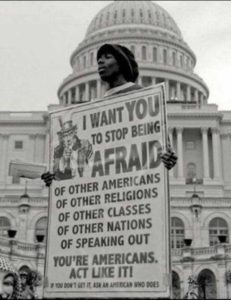

One of the basic principles of democracy is “one person, one vote”. Other criteria for an efficient and robust model of democracy include an informed and critically inclined citizenry and the presence of a political culture catering to the “common good” instead of the self-centred whims and boundless greed of the rich and powerful.

One of the basic principles of democracy is “one person, one vote”. Other criteria for an efficient and robust model of democracy include an informed and critically inclined citizenry and the presence of a political culture catering to the “common good” instead of the self-centred whims and boundless greed of the rich and powerful.

Unfortunately, none of the above are representative features of American democracy: American politics is increasingly ruled by a moneyed oligarchy that calls the shots, while the country has shifted from a society of citizens to a society of consumers.

The highly flawed nature of American democracy has become more striking in recent years as the absence of political ethos works in tandem with massive economic inequality, job insecurity, and a declining standard of living to produce conditions ripe for corruption, manipulation of public opinion, and authoritarianism.

Indeed, the presidential election of 2016 speaks volumes of the crisis facing American democracy, making the world’s richest and most powerful nation resemble a “banana republic”.

Electing the electors

For starters, the contest for the White House was between a megalomaniac billionaire with no experience whatsoever in the “art of the possible” (but competent with entanglements with foreign governments and leaders, and an uncanny ability in twisting the tax law to his advantage) and a lifelong politician, widely regarded as a darling of Wall Street as well as a warmonger.

If this is not a sign of a moribund political system, the candidate elected to become the 45th president of the United States lost the popular vote by a bigger margin than of any other US President. Donald Trump was elected president by trailing Hillary Clinton by nearly three million votes.

This “democratic” anomaly is owing to the fact that US presidents are chosen by electors, not by popular vote.

To be sure, there is nothing in the constitution that grants American voters the right to choose their president. When American voters go to the polls to vote for a presidential candidate, what they are essentially doing is casting a vote for their preferred party’s nominated slate of electors.

The electoral college system is democracy’s ugliest anachronism. Because of the design of the electoral college, intended by the founding fathers to prevent the masses from choosing directly who will run the country, a candidate can win the nationwide popular vote and still lose the presidency.

This is what happened in 2000, when Al Gore won nearly half a million more votes than George W Bush, but it was Bush who won the presidency by being declared winner in the state of Florida by less than 540 votes. And, of course, history repeated itself in the 2016 election. Read more

- by: Marcus Rolle & Alexandra Boutri

“We live in ominously dangerous times” stated the opening line of an article by C.J. Polychroniou (with Lily Sage) titled “A New Economic System for a World in Rapid Disintegration,” which was recently published in Truthout. And while the aforementioned piece was mainly a scathing critique of global neoliberal capitalism and a call for a new system of economic and social organization, its underlying thesis was that the world system is breaking down and that contemporary societies are in disarray.

“We live in ominously dangerous times” stated the opening line of an article by C.J. Polychroniou (with Lily Sage) titled “A New Economic System for a World in Rapid Disintegration,” which was recently published in Truthout. And while the aforementioned piece was mainly a scathing critique of global neoliberal capitalism and a call for a new system of economic and social organization, its underlying thesis was that the world system is breaking down and that contemporary societies are in disarray.

Is the (Western) world in shambles? We interviewed C.J. Polychroniou about the current world situation, with emphasis on developments in Europe and the United States, and sought his views on a host of pertinent political, economic and social issues, including the rise of the far right and the capitulation of the left.

Marcus Rolle and Alexandra Boutri: Let’s start by asking — what exactly do you have in mind when you say, “We live in ominously dangerous times?”

C.J. Polychroniou: We live in a period of great global complexity, confusion and uncertainty. It should be beyond dispute that we are in the midst of a whirlpool of events and developments that are eroding our capability to manage human affairs in a way that is conducive to the attainment of a political and economic order based on stability, justice and sustainability. Indeed, the contemporary world is fraught with perils and challenges that will test severely humanity’s ability to maintain a steady course towards anything resembling a civilized life.

For starters, we have been witnessing the gradual erosion of socio-economic gains in much of the advanced industrialized world since at least the early 1980s, along with the rollback of the social state, while a tiny percentage of the population is amazingly wealthy beyond imagination that compromises democracy, subverts the “common good” and promotes a culture of dog-eat-dog world.

The pitfalls of massive economic inequality were identified even by ancient scholars, such as Aristotle, and yet we are still allowing the rich and powerful not only to dictate the nature of society we live in but also to impose conditions that make it seem as if there is no alternative to the dominance of a system in which the interests of big business have primacy over social needs.

In this context, the political system known as representative democracy has fallen completely into the hands of a moneyed oligarchy which controls humanity’s future. Democracy no longer exists. The main function of the citizenry in so-called “democratic” societies is to elect periodically the officials who are going to manage a system designed to serve the interests of a plutocracy and of global capitalism. The “common good” is dead, and in its place we have atomized, segmented societies in which the weak, the poor and powerless are left at the mercy of the gods.

I contend that the above features capture rather accurately the political culture and socio-economic landscape of “late capitalism.” Nonetheless, the prospects for radical social change do not appear promising in light of the huge absence of unified ideological gestalts guiding social and political action. What we may see emerge in the years ahead is an even harsher and more authoritarian form of capitalism.

Then, there is the global warming phenomenon, which threatens to lead to the collapse of much of civilized life if it continues unabated. The extent to which the contemporary world is capable of addressing the effects of global climate change — frequent wildfires, longer periods of drought, rising sea levels, waves of mass migration — is indeed very much in doubt. Moreover, it is also unclear if a transition to clean energy sources suffices at this point in order to contain the further rising of temperatures. To be sure, global climate change will produce in the not-too-distant future major economic disasters, social upheavals and political instability.

If the climate change crisis is not enough to make one convinced that we live in ominously dangerous times, add to the above picture the ever-present threat of nuclear weapons. In fact, the threat of a nuclear war or the possibility of nuclear attacks is more pronounced in today’s global environment than any other time since the dawn of the atomic age. A multi-polar world with nuclear weapons is a far more unstable environment than a bipolar world with nuclear weapons, particularly if we take into account the growing presence and influence of non-state actors, such as extreme terrorist organizations, and the spread of irrational and/or fundamentalist thinking, which has emerged as the new plague in many countries around the world, including first and foremost the United States.

Read more

Photo: youtube.com

Participatory economics has long been proposed as an alternative to capitalism and centralized planning. It remains, nonetheless, a misunderstood concept and continues to find opposition among both capitalists and anticapitalists. So, what exactly is “participatory economics” and how does it fit with the socialist vision of a classless society? In this interview, Michael Albert, founder of Z Magazine and one of the leading advocates of the movement toward a “participatory society” addresses key questions about capitalism, socialism and the implications of a participatory economy.

C.J. Polychroniou: Any discussion of economic systems revolves essentially around two apparently opposed poles — capitalism and socialism. In reality, however, most of the actually existing economies in the modern world have been “mixed economies.” Be that as it may, what’s your understanding of capitalism, and what are the distinguished features of socialism?

Michael Albert: Capitalism is an economic system in which people own workplaces and resources, employ workers for wages to produce outputs and overwhelmingly employ market allocation to mediate how the outputs are dispersed. Typically also, and I would say inevitably if it has the first two features, it will also have what I call a corporate division of labor in which about 80 percent of the workforce does overwhelmingly rote, obedient and mainly disempowering tasks, and the other 20 percent monopolizes empowering tasks. Income will be a function of property and bargaining power.

In my view, there are, therefore, three main classes in capitalism: a working class doing the disempowering work [whose members] have low income and nearly no influence; a capitalist class that employs workers, sells their product and tries to reap profits, and which, due to those profits, enjoys tremendous wealth and dominant power; and a coordinator class situated between the other two, doing the empowering work, and, due to that, having the power to accrue high income and substantial influence.

Socialism is trickier to pinpoint. For some it is an economy in which those who produce decide all the outcomes, so it is classless, or, if you like, has only one class, the workers, all of whom have the same overall economic status. For others, socialism is a society with a polity that greatly influences economic outcomes on behalf of the public, even while owners still reap profits. For still others, socialism is an economy that has public or state ownership plus central planning or markets for allocation.

I think this last is what socialism in practice has been, plus having a corporate division of labor that arises inexorably due to its forms of allocation but is also preferred, plus an authoritarian polity. However, I call this type of economy “coordinatorism” for the clear and obvious reason that its institutions eliminate capitalist ownership but elevate the 20 percent coordinator class to ruling status. Out with the old boss: the owner, the capitalist class; in with the new boss: managers, doctors, lawyers and so on, the coordinator class.

So, if you like socialism because you hope for classlessness, you are pretty likely nowadays to have in mind some kind of worker-controlled economy but typically without offering clarification of what institutions can deliver that.

If you don’t like the idea of full classlessness — either fearing that it would be dysfunctional or wishing to maintain coordinator class advantages — as socialism, you likely have in mind some variant on classical Marxist coordinatorist formulations.

I prefer classlessness — which, in my mind, is like preferring freedom to servitude — but I also see a need to have an institutional vision able to give it substance, which is what participatory economics, or if you prefer, participatory socialism tries to provide.

Read more

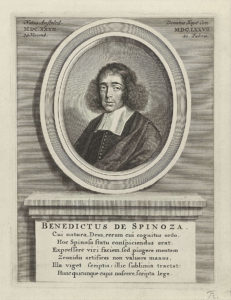

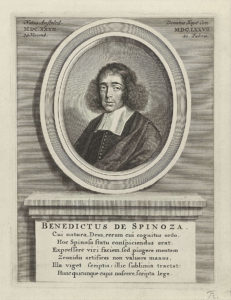

The Spinoza Web is a website that seeks to make the Dutch philosopher Benedictus de Spinoza (1632-1677) accessible to a wide range of users from interested novices to advanced scholars, and everything in between. It is a continually developing, active project whose success depends on its users. Please contact us with feedback, suggestions, and ideas!

The Spinoza Web is a website that seeks to make the Dutch philosopher Benedictus de Spinoza (1632-1677) accessible to a wide range of users from interested novices to advanced scholars, and everything in between. It is a continually developing, active project whose success depends on its users. Please contact us with feedback, suggestions, and ideas!

At present our website offers two points of entry. The ‘Timeline Experience’ tells the story of Spinoza, using rich graphic and other supporting material through which the user can navigate to enter and experience his very world. The ‘Database Search’ is a gateway to an enormous repository for the study of Spinoza, whose goal is eventually to assemble all first-hand documentation pertaining to him. Attractively designed without compromising on scholarly standards, our website promotes a source-based contextual approach to Spinoza who, revered and reviled, has had countless rumours and myths attached to his name over the course of the centuries.

‘Spinoza’s web’-project

The Spinoza Web is a creation of the ‘Spinoza’s Web’-project of the Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies at Utrecht University, funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). It traces back to an early initiative of its main executive, Jeroen van de Ven, and was implemented by the project’s principal investigator, Piet Steenbakkers, who had entertained a long-time wish for a website dedicated to Spinoza. In 2014 postdoctoral researcher Albert Gootjes joined their ranks in a largely advisory capacity. Later that year the team commissioned the Rotterdam-based advertising agency Nijgh, which gladly welcomed the new challenge of combining creative inspiration with scholarly rigour.

Beta release

After extensive planning and user tests, November 2016 saw the beta release of The Spinoza Web, notably featuring the ‘Timeline Experience’ and Database with entries largely based on the historical and bibliographical research by Jeroen van de Ven. Subsequent releases are scheduled to boost the ‘Database Search’ by making available in open access Spinoza’s writings both in their original editions and in an authoritative English translation. Further plans include the addition of an interactive element facilitating Spinoza studies. To help us realize our pursuits, we welcome all contributions including but not limited to financial support. Potential contributors are encouraged to get in touch using the Contact page.

See: http://spinozaweb.org/