The Winner Of The 2020 Election Won’t Be Inheriting A Genuine Democracy

Today’s election is widely regarded as the most important national election in recent U.S. history, voters remain divided and polarized over what should be essentially the future of the country. Issues over racism, immigration, guns, women’s rights, police brutality and climate change are what essentially divide Republican voters from Democrats. The former, galvanized by the extreme and divisive rhetoric of a racist and reactionary president, wish to preserve the values of “traditional America” (white supremacy and patriarchy, militarism, rugged individualism and religiosity), while Democrats worry that another four years of Donald Trump in office will spell the end of democracy.

Today’s election is widely regarded as the most important national election in recent U.S. history, voters remain divided and polarized over what should be essentially the future of the country. Issues over racism, immigration, guns, women’s rights, police brutality and climate change are what essentially divide Republican voters from Democrats. The former, galvanized by the extreme and divisive rhetoric of a racist and reactionary president, wish to preserve the values of “traditional America” (white supremacy and patriarchy, militarism, rugged individualism and religiosity), while Democrats worry that another four years of Donald Trump in office will spell the end of democracy.

Is destroying or saving U.S. democracy what the upcoming election is all about? In this interview, political scientist C.J. Polychroniou says it is high time that we did away with the political rhetoric when it comes to U.S. democracy and look at the facts: The U.S. has a highly flawed system of democratic governance and doesn’t even rank among the top 20 democracies in the Western world, and thus is in dire need of major repair. In fact, Polychroniou argues, it is far more accurate to describe the United States as an oligarchy, a regime where an economic elite and powerful organized interests are in virtual control of the policy agenda on most issues of critical importance to public interest while average people are mainly political bystanders.

Alexandra Boutri: The general consensus among a significant percentage of voters opposed to Donald Trump is that the upcoming election represents a pivotal moment in U.S. politics, for what is at stake is nothing else than the future of democracy itself. True, or an exaggeration?

C.J. Polychroniou: Trump’s presidency has been marked from the beginning by lies, strong authoritarian impulses, contempt for the media and disdain for science, big gifts for the rich and big cuts for the poor, and complete disregard for the environment. His political posturing is outright neo-fascist, and, as such, this president surely has little concern about the subtleties of democratic governance. Of course, U.S. democracy was in a crisis long before Trump came to power. In fact, one could easily make the argument that the U.S. is not a true democracy at all (it qualifies as a mere procedural democracy), and was never meant to be when you get to understand the architecture of the Constitution, who the framers were, and why they opted to ditch, in the manner of a coup, the Articles of Confederation, during the Constitutional Convention of 1787. In fact, the drafting of the Constitution itself was not a democratic process: The delegates were sent there by state legislatures with a mandate to revise the Articles of Confederation, but, instead, they worked in total secrecy in producing an entirely new legal document for the future government of the United States.

The Constitution that the framers produced, with its system of checks and balances, was as a legal document way ahead of its time, since back then, monarchy was the prevailing form of political rule throughout the world. But in addition to designing a system of governance that would prevent the rise of an absolute ruler, the framers also wanted to make sure that the masses themselves would not be in a position to determine political outcomes. Indeed, the framers were seeking a form of government that would keep the elites safe both from the caprice of absolute rulers and from the whims of the rabble. They were indeed in complete agreement with the view of John Jay, one of the so-called Founding Fathers and the first Chief Justice, when he said, “Those who own the country ought to govern it.” Hence the purpose behind the introduction of the Electoral College, which blatantly violates the very basic principle of democracy, i.e., one person, one vote; hence also the anti-democratic nature of the Senate, where states with very small populations get the same number of senators as states with huge populations.

The U.S. is also the only democracy in the world where politicians are actively involved in manipulating the boundaries of electoral districts. Political gerrymandering has a long history in the U.S., but as Common Cause National Redistricting Director Kathay Feng pointedly put it, “In a democracy, voters should choose their politicians, not the other way around.”

In addition, federal election campaigns funded entirely by private money makes a mockery of the democratic process for electing public officials, while the “winner-take-all” system, which is not in the Constitution and therefore can be changed without a constitutional amendment, can easily be regarded as undemocratic under modern election law jurisprudence, as has correctly been pointed out by former Republican governor of Massachusetts, William Weld, and law professor Sanford Levinson.

In sum, there is no other democracy in the advanced industrialized world with the “undemocratic” features of the system of democracy found in the U.S., including its two-party system which severely limits public dialogue and debate among competing political views. Little surprise, therefore, why even the conservative weekly magazine The Economist has labeled the U.S. a “flawed democracy.” As a matter of fact, U.S. democracy does not even rank among the top 20 democracies in the Western world, according to the Democracy Index compiled by the Economist Intelligence Unit. The U.S. form of governance fits far more perfectly with that of classical oligarchy, although in the last four years, the country also had a leader who behaved more in tune with the traits of the tyrannical man outlined in Plato’s Republic.

Een bom in Londen – Joseph Conrad, zijn roman The Secret Agent en een Franse kleermaker

De Pools-Engelse schrijver Joseph Conrad (1857-1924), auteur van onder meer Heart of Darkness en Lord Jim, liet zich voor zijn roman The Secret Agent (1907) inspireren door een ware gebeurtenis: een poging tot een bomaanslag op het Greenwich Royal Observatory in 1894. De gebeurtenis was niet meer tot dan de aanleiding voor de roman, stelde Conrad. Van de achtergronden ervan zou hij niet op de hoogte zijn geweest. Maar was dat wel zo? Wat waren dan deze achtergronden?

Revolutionairen

In The Secret Agent beschrijft Conrad hoe Adolf Verloc, een winkelier in brocante, pornografie en voorbehoedsmiddelen, de broer van zijn vrouw aanzet een aanslag te plegen op het Greenwich Royal Observatory. Het verhaal speelt zich af in 1886. Verloc behoort tot een geheime anarchistische groep die in Londen opereert. Maar ook verricht hij hand en spandiensten in opdracht van een buitenlandse – Russische? – ambassade. Een diplomaat van de ambassade vertelt dat zijn land de Britse respons op de activiteiten van revolutionairen uit zijn land te zwak vind. Een eventuele aanslag zou de waakzaamheid zeker opvoeren. Verloc weet zijn inwonende zwager Stevie, een jongen met een verstandelijke beperking, aan te zetten een bomaanslag te plegen op het Greenwich Royal Observatory.

Ook heeft Verloc goede contacten met hoge politiefunctionarissen. Die laten hem bij de voorbereidingen oogluikend zijn gang gaan.

Met een bom in de zak van zijn overjas, struikelt Stevie halverwege het pad heuvelopwaarts naar het observatorium en blaast zichzelf op. Een briefje dat wordt gevonden in de resten van zijn overjas, zet de politie op het spoor van Verloc. Wanneer zijn vrouw Winnie achter de waarheid komt, zijn de gevolgen voor Verloc noodlottig: hij wordt door Winnie vermoord.

Wanneer Winnie daarna vlucht en een nieuw leven wil beginnen, blijkt ook haar geluk van korte duur.

Persiflage

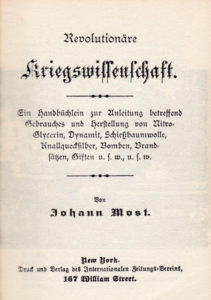

Naast dit tragische familiedrama kent het boek ook een luchtiger kant. Zo is de karakterschets die Conrad geeft van de anarchistische  kringen waarin Verloc verkeert, nogal dik aangezet, een persiflage bijna. De leden van zijn geheime anarchistische groepje worden neergezet als grotesk orerende beroepsrevolutionairen, die soms de zelfkant van de maatschappij nauwelijks ontstegen lijken te zijn. Karikaturale personages weliswaar, maar toch geïnspireerd op bestaande personen uit de anarchistische beweging. Michaelis, de filosoof van de groep, lijkt geënt op Michael Bakoenin en Peter Kropotkin, twee van de grote denkers van het anarchisme. Een ander lid, bijgenaamd The Professor, is een deskundige in explosieven, en vertoont grote gelijkenis met de Duitse anarchist Johann Most, onder meer auteur van het boekwerkje Revolutionäre Kriegswissenschaft, een handleiding tot het fabriceren van bommen.

kringen waarin Verloc verkeert, nogal dik aangezet, een persiflage bijna. De leden van zijn geheime anarchistische groepje worden neergezet als grotesk orerende beroepsrevolutionairen, die soms de zelfkant van de maatschappij nauwelijks ontstegen lijken te zijn. Karikaturale personages weliswaar, maar toch geïnspireerd op bestaande personen uit de anarchistische beweging. Michaelis, de filosoof van de groep, lijkt geënt op Michael Bakoenin en Peter Kropotkin, twee van de grote denkers van het anarchisme. Een ander lid, bijgenaamd The Professor, is een deskundige in explosieven, en vertoont grote gelijkenis met de Duitse anarchist Johann Most, onder meer auteur van het boekwerkje Revolutionäre Kriegswissenschaft, een handleiding tot het fabriceren van bommen.

Centraal staat in het boek echter de aanslag die Stevie moet gaan plegen: een vrijwel exacte kopie van wat er op 15 februari 1894 gebeurde op het wandelpad naar het Greenwich Royal Observatory.

Motieven

Op die dag verliet de Franse anarchist Martial Bourdin zijn kamer in Fitzroy Street in Londen.

Bij zich droeg hij een handgemaakte bom. Op Westminster nam hij de tram naar Greenwich Park. Daar nam hij een pad naar het Royal Observatory. Halverwege de heuvel kwam hij vermoedelijk ten val waarbij de bom tot ontploffing kwam. Zwaar gewond werd Bourdin naar het dichtstbijzijnde ziekenhuis vervoerd. Zonder dat hij zijn naam noemde of iets zei over zijn motieven, overleed hij daar een half uur later. Waarschijnlijk had hij een aanslag willen plegen op het observatorium.

Het is altijd een raadsel gebleven wat Bourdins beweegredenen voor de aanslag waren. Het observatorium gold niet als een markant kapitalistisch symbool. Ook als symbool van de Britse staat lijkt het vergezocht. Iets als de Houses of Parlement zou in dat geval meer voor de hand gelegen hebben. Het observatorium diende immers in de eerste plaats de wetenschap.

Wel bevond zich in het observatorium de klok die sinds 1852 de Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) aangaf. In 1880 besloot de Britse regering deze als standaardtijd te hanteren. Met enige fantasie valt hooguit te beargumenteren dat de klok een symbool vormde voor de controle die de Britse staat dankzij de GMT uitoefende over het dagelijks leven van de arbeidende bevolking. Maar deze redenering lijkt vergezocht.

Een andere vraag die politieonderzoekers zich stelden was of de actie van Bourdin een soloactie was of dat hij bij de voorbereiding hulp had gehad. Opvallend was verder dat Bourdin een groot geldbedrag bij zich droeg. Waarom? Wilde hij na zijn daad mogelijk snel het land verlaten? En hoe was de Fransman eigenlijk in Londen verzeild geraakt en wat voerde hij er uit?

StAWIL: Steun Acroniem – Weg met Initiaal- of Letterwoord

In het spraakgebruik wordt elke schrijfwijze die korter is dan het volledige woord of de volledige woorden – KNVB, NPO, bios, svp, VARA, p.n.o.k., O.T, bv. – een afkorting genoemd. En als er al een onderscheid wordt aangebracht, is het tussen letterwoord – UNO, JAC – en afkorting de rest.

In het spraakgebruik wordt elke schrijfwijze die korter is dan het volledige woord of de volledige woorden – KNVB, NPO, bios, svp, VARA, p.n.o.k., O.T, bv. – een afkorting genoemd. En als er al een onderscheid wordt aangebracht, is het tussen letterwoord – UNO, JAC – en afkorting de rest.

Er is een verfijnder – en zinniger – indeling te bedenken. Dat is bijvoorbeeld gedaan door Dr. C.G.L. Apeldoorn. In het ‘Voorbericht’ bij zijn Afkortingen (Utrecht, 1983) oppert hij een indeling in verkortingen, afkortingen en initiaalwoorden.

De driedeling van Apeldoorn maakt het volgende onderscheid :

1. verkorting, waarbij het eind van een woord – prof(essor) – of het begin van een woord – (auto)bus – wordt weggelaten;

2. afkorting, waarbij van een of meer woorden een of meer letters gebruikt worden: m.m., B.Z.N., v.m., h., n.v.t.;

3. initiaalwoord.

Die laatste groep valt in drie soorten uiteen: 1. de initialen vormen een uitspreekbaar woord (AVRO, FIFA); 2. ze zijn niet als één woord uit te spreken (CDA, NCB, PVC); 3. om er een normaal uit te spreken woord van te maken, neemt men meer dan alleen de beginletters (BENELUX).

Een bezwaar tegen Apeldoorns indeling is, dat er drie te onderscheiden vormen onder één term (initiaalwoord) gebracht worden, terwijl één daarvan (PSP, DDR, WVC, enz.) onder zijn eigen definitie van ‘afkorting’ valt en een andere (FEBECOOP: Federatie der Belgische Coöperatieven) zich niet tot de initialen beperkt.

De resterende vorm (UNIFIL, NOS) is derhalve de zuiverste vorm van het initiaalwoord, en het is die vorm die nog altijd hardnekkig met ‘letterwoord’ wordt aangeduid. Een foeilelijk woord en nog zinledig ook, al was het maar omdat elk woord per definitie een letterwoord is, zoals ook elk getal een cijfergetal is.. Die nietszeggende, hoogst verwarrende term dient snel vervangen te worden door een betere, een duidelijke, een informatie-dragende naam. Acroniem, bijvoorbeeld.

Er is geen reden waarom dit type afkorting in het vervolg in het Nederlands níét acroniem zou heten.

En er zijn – ten minste twee – uitstekende redenen waarom we ze voortaan wèl zo zouden noemen.

De eerste is dat het initiaal- of letterwoord in alle moderne vreemde talen met deze term wordt aangeduid. De tweede reden is dat het woord acroniem is opgebouwd uit twee delen die beide in tal van gebruikelijke Nederlandse woorden voorkomen. Acro, van het Griekse akron (punt, spits, uiteinde), verschijnt bijvoorbeeld in acropolis (letterlijk: stad op de top), acrobaat (van akrobatos: op de tenen gaand) en acrofobie (hoogtevrees). Tot de mooiste reken ik acromegalie (het Griekse megas is groot; vandaar de afwijking die reuzengroei van handen en voeten veroorzaakt) en acrostichon, het gedicht waarvan de eerste letters van elke versregel een woord, naam of uitspraak vormen.

Het tweede deel van acroniem stamt van het Griekse onuma (naam) en komt voor in onder meer pseudoniem, synoniem en anoniem. Zonder overdrijven kan daarom geconcludeerd worden dat ‘acro’ en ‘niem’ al lang en in tal van samenstellingen in onze taal gebruikt worden, alleen nog niet of nauwelijks in combinatie met elkaar. Er is dus alle reden om wat tot nu toe doorgaans met letterwoord werd aangeduid, namelijk een afkorting die zich als één woord laat uitspreken, voortaan acroniem te noemen.

Historie

De laatste tijd, laten we zeggen vanaf de Tweede Wereldoorlog, is er een explosie van acroniemen, maar dat wil niet zeggen dat het verschijnsel niet al veel ouder is. Het oudste voorbeeld komt wellicht uit de bijbel: de tekst op het bord dat boven Christus’ hoofd aan het kruis bevestigd werd.

Die tekst luidt: INRI, het acroniem van het Latijnse Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudaeorum, Jezus van Nazareth, Koning der Joden.

In de begintijd van het christendom was ICHTHUS (Grieks voor vis) het symbool voor Christus en diende het als wachtwoord voor de geheime, want verboden bijeenkomsten van de eerste christenen. ICHTHUS is de afkorting van Iesous CHristos THeou hUios Soter, Jezus Christus, Zoon van God, Verlosser.

Veel meer biedt de historie niet, tot in 1602 de VOC, de Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, werd opgericht, al is het twijfelachtig of dat toen als één woord werd uitgesproken.

Het eerste moderne acroniem danken we waarschijnlijk aan het ontstaan van de Algemeene Vereniging Radio Omroep in 1923. Ook hierbij is het trouwens de vraag of er van het begin af AVRO gezegd is. Het lijkt me geen onredelijk criterium dat iets niet alleen een acroniem kàn zijn, maar het in de praktijk ook is. Om die reden valt bijvoorbeeld KRO uit de boot. Veilig kan gesteld worden dat het zuivere acroniem een kind van de twintigste eeuw is.

UNO en ONU

Een sector waar al snel veel acroniemen verschenen, was de voetbalsport. Met het toenemen van de FC Plaatsnaam verdwijnen de mooiste uit de publiciteit, maar bij de ware liefhebbers worden nostalgische herinneringen opgeroepen door namen als DOS en NOAD: Door Oefening Sterk; Nooit Ophouden, Altijd Doorgaan. Dat waren de dagen van Rigtersbleek en Limburgia, Enschedesche Boys en Zwartemeer. Die tijd komt nooit meer terug.

De Tweede Wereldoorlog gaf een ferme stoot tot de verdere opmars. Tot de meest praktische behoorde LIB, dat zowel in het Engels (Light Infantery Batallion) als in het Nederlands (Lichte Infanterie Bataljon) inzetbaar was, en tot de welluidendste AMACAB (Allied Military Administration, Civil Affairs Branch).

Maar pas na die oorlog nam het gebruik van acroniemen serieuze vormen aan. De UNO ontstond, de United Nations Organization, en de NATO, de North Atlantic Treaty Organization. In het Frans bestaan ze precies andersom maar niet minder acroniem: ONU en OTAN. Door de UNO werden andere organisaties in het leven geroepen. Daaronder UNICEF, het United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund, en UNESCO, de United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

Vruchtbare bronnen zijn ook het onderwijs – de Mammoetwet bracht ons, onder veel meer, MAVO en HAVO, LEAO, MEAO en HEAO – en de sociaal-economische hoek. De SER, de Sociaal-Economische Raad, heeft zijn licht laten schijnen over deels door de tijd al achterhaalde onderwerpen als de VAD, de VermogensAanwasDeling, de WIR, de Wet op de InvesteringsRekening, APO, een ArbeidsPlaatsenOvereenkomst, en VUT, Vervroegde UitTreding.

Tot de jongste lichting behoren acroniemen uit het ARC, het Alternatieve Relaties Circuit, zoals de LAT-relatie, Living Apart Together, de WOP-relatie (wippen, ontbijten, pleite) en de BOM, de Bewust Ongehuwde Moeder.

Veel komen er ook voort uit het ruimte-onderzoek. Bekend zijn de ANS (Astronomische Nederlandse Satelliet) en de IRAS (InfraRed Astronomy Satellite), maar minder lees je over MRUASTAS, een Medium-Range Unmanned Aerial Surveillance and Target Acquisition System, en DISCO, Dual Irradiance and Solar Constant Orbiter.

Aan sommige voorbeelden – WIR, DISCO – is te zien dat er wel eens een paar tussenwoordjes weggesmokkeld moeten worden; bij andere – ICHTHUS, RADAR (RAdio Detecting And Ranging) – wordt meer dan alleen de beginletter van elk woord gebruikt. Ook dat is een argument vóór het gebruik van de term acroniem (acro betekent immers punt, spits) boven namen als initiaalwoord of beginletterwoord.

Bloody Awful

Het is een zeker teken dat iets leeft in de taal, als er door de gebruikers van die taal mee gespeeld wordt, als er varianten op bedacht worden of grappen mee gemaakt. Voor HEMA circuleert behalve de officiële – Hollandse EenheidsprijzenMaatschappij Amsterdam – ook een officieuze invulling: Hier Etaleert Men Afval. En NOZEM heette de afkorting te zijn van Nederlandse Onderdaan Zonder Enig Moraal.

Dankbare voorwerpen van milde spot zijn de namen van luchtvaartmaatschappijen. Zo wordt de voormalige SABENA in plaats van Société Anonyme Belge d’Exploitation de la Navigation Aérienne ook opengevouwen tot Sauf Accidents, Bien Entendu, Nous Arriverons (ongelukken daargelaten, wel te verstaan, zullen we aankomen). En GARUDA, de Indonesische luchtvaartmaatschappij, kreeg als postkoloniale variant: Good And Reliable Under Dutch Administration (goed en betrouwbaar onder Nederlands beheer). Britse luchtvaartmaatschappijen kunnen helemaal geen goed doen: voor BOAC – inmiddels ter ziele – bedachten collega’s van de concurrentie Better On A Camel en voor BA (British Airways) Bloody Awful.

Niet zelden worden acroniemen voor de gelegenheid bedacht. Dat lijkt het geval met het 13 letters tellende EENHEIDSWORST: de Enige Echte Nederlandse Hardwerkende En Intellectueel Denkende Sportvereniging Welke Onder Rustige Situaties Traint.

Wie er eenmaal oog voor heeft, ontdekt voortdurend nieuwe en verrassende kanten aan het acroniem. Zoals VOLDULOSTA, de Vereniging van Oud-Leerlingen Der ULO-School Te Aalsmeer, dat een acroniem binnen een acroniem bevat. Of de ware achtergrond van het ogenschijnlijk nederige woordje PEC, de naam van een voetbalclub uit Zwolle. In PEC gingen ooit twee clubs samen wier namen het Champions League-gebeuren een onverwachte glans gegeven zouden hebben, waren zij niet opgegaan in de Prins Hendrik Ende Desespereert Niet Combinatie.

De komende tijd zal, zo moet maar gehoopt worden, het makkelijk uit te spreken en beter te onthouden acroniem in steeds meer gevallen verkozen worden boven de traditionele afkorting.

Voorbeelden te over in de commercie, maar vooral in de techniek, zoals in de astronomie, de wapenwedloop (AWACS, START) en de computerwereld: BASIC (Beginners All-purpose Symbolic Instructions Code) of COBOL (COmmon Business Oriented Language).

En anders moet misschien maar de Actiegroep Steun Acroniem – Weg met Initiaal- of Letterwoord opgericht worden.

—

Robert-Henk Zuidinga (1949) studeerde Nederlandse en Engelse Moderne Letterkunde aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam. Hij schrijft over literatuur, taal- en bij uitzondering – over film.

De drie delen Dit staat er bevatten de, volgens zijn eigen omschrijving, journalistieke nalatenschap van Zuidinga. De boeken zijn in eigen beheer uitgegeven. Belangstelling? Stuur een berichtje naar: info@rozenbergquarterly.com– wij sturen uw bericht door naar de auteur.

Dit staat er 1. Columns over taal en literatuur. Haarlem 2016. ISBN 9789492563040

Dit staat er II, Artikelen en interviews over literatuur. Haarlem 2017. ISBN 9789492563248

Dit staat er III. Bijnamen en Nederlied. Buitenlied en film, Haarlem 2019. ISBN 97894925636637

The US Chose Endless War Over Pandemic Preparedness. Now We See The Effects

The United States of War – A Global History of America’s Endless Conflicts, from Columbus to the Islamic State. ISBN: 9780520300873

The United States has the longest record of war-fighting in modern history. Why that is the case is not a question that has an easy answer; suffice to say, however, that militarism and violence run like a red thread throughout U.S. political history, with enormous costs both for the domestic economy and the world at large, as a recently published book by David Vine makes plainly clear. In fact, the militarist mentality is strongly reinforced by the Trump administration in spite of the fact that the current president claims to have an aversion to “endless wars.” In this exclusive Truthout interview, Vine, a professor of anthropology at American University in Washington, D.C., addresses critical questions about U.S. war culture and Trump’s own contribution to the violence that has always been foundational to U.S. culture.

C.J. Polychroniou: Your latest book, The United States of War: A Global History of America’s Endless Conflicts, from Columbus to the Islamic State, is a detailed survey of the U.S.’s obsession with militarism and war. Have you come to a definite conclusion or explanation as to why the United States has been at war for about 225 of the 243 years since its independence?

David Vine: There is, of course, no simple answer to this incredibly important question. According to my research, the U.S. military has been at war or engaged in other combat in all but 11 years of U.S. history — 95 percent of the years the United States has existed. My book shows how the huge collection of U.S. military bases abroad provides a key — or a kind of lens — to help understand why the United States has been fighting almost without pause since 1776. Bases abroad, bases beyond U.S. borders show how U.S. political, economic and military leaders — shaped by the forces of history, capitalism, racism, patriarchy, nationalism and religion — have used taxpayer money to build a self-perpetuating system of permanent, imperialist war revolving around an often-expanding collection of extraterritorial military bases. These bases have expanded the boundaries of the United States, while keeping the country locked in a state of nearly continuous war that has largely served the economic and political interests of elites and left tens of millions dead, wounded and displaced.

To be clear, my argument is not that U.S. bases abroad are the singular cause of this near-endless fighting. Indeed, my book shows how the answer to why the U.S. government has fought so constantly lies in the capitalist profit-making desires of businesses and elites, in the electoral interests of politicians, and in the forces of racism, militarized masculinity, nationalism and missionary Christianity, among other dynamics.

U.S. bases abroad, however, have played a key and long overlooked role in the pattern of near-constant U.S. fighting: that is, since independence, bases that U.S. leaders have built beyond the borders of the United States not only have enabled wars but also have made offensive imperialist wars more likely. While U.S. leaders often portray bases abroad as defensive in nature, the opposite is generally the case: bases built on the territory of other peoples have tended to be offensive in nature, providing a launchpad for yet more wars. This has tended to create a pattern in which bases abroad have led to wars that have led to the construction of new bases abroad that have led to new wars that have led to new bases and so on.

Can you offer us a quick assessment of the overall costs of the “global war on terror?”

It’s impossible to capture the immensity of the catastrophe that the so-called “global war on terror” has inflicted. Around 15,000 U.S. military personnel and contractors have died in wars the U.S. government has waged since invading Afghanistan in October 2001. Hundreds of thousands of troops have returned with amputations, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), traumatic brain injuries, and other physical and mental damage. As of 2018, 1.7 million veterans had reported a wartime disability.

Across the countries where the U.S. military has fought, the death toll is at least 50 times higher than the U.S. death toll: In Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Pakistan and Yemen alone, an estimated 755,000 to 786,000 civilians and combatants have died as a result of combat. Total deaths may reach 3.1-4 million or more, including those who have died as a result of disease, hunger and malnutrition caused by the wars. Entire neighborhoods, cities and societies have been shattered by these wars. The number injured and traumatized surely extends into the tens of millions. At least 37 million people have been displaced from their homes during U.S. fighting in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Pakistan, the Philippines, Somalia, Syria and Yemen. For perspective, 37 million is about as many people as live in California and in Texas and Virginia combined. Thirty seven million displaced is more than those displaced by any war anywhere in the world since at least 1900, with the exception of World War II.

The U.S. government and the United States as a country are not single-handedly responsible for all the death, displacement and destruction of these wars. Other governments and combatants also bear significant responsibility. However, the U.S. government bears disproportionate responsibility, especially for the wars it has launched (Afghanistan, the overlapping war in Pakistan, and Iraq), the wars it has escalated (Libya and Syria), and the wars in which U.S. forces have been significant combatants (Yemen, Somalia and the Philippines). Alongside U.S. funding for and involvement in combat in a total of at least 24 countries since 2001, the rhetoric of the “war on terror” alone has also fueled wars and violence worldwide.

Alongside the human damage, the financial costs of the so-called war on terror are so large, they’re nearly incomprehensible. As of October 2020, the U.S. government has spent or obligated a minimum of $6.4 trillion on the post-2001 wars, including the costs of future veterans’ benefits and interest payments on the money borrowed to pay for the wars. The actual costs are likely to run hundreds of billions or trillions more, depending on when we force our politicians to bring these seemingly endless wars to an end.

While it’s incredibly hard to fathom $6.4 trillion in taxpayer funds vanished, the catastrophe is compounded when we consider how else the U.S. government could have spent such incredible sums of money. What could these trillions have done to provide universal health care, to rebuild public schools, to build affordable housing, to end homelessness and hunger, to rebuild crumbling civilian infrastructure, to prepare for pandemics? In addition to the 3-4 million who have likely died in the wars the U.S. government has fought since 2001, how many more have died because of the investments the U.S. government did not make? These are questions that, I have to say, should make us weep.

In trying to wrap our minds around the unbelievable human and financial costs of the so-called “war on terror,” we also have to remember that this war has also been a catastrophic failure on its own terms: the main result of the “war on terror” has been to spread terror and dramatically expand the number of groups and people who would engage in terrorist attacks on U.S. citizens and others civilians worldwide as a political tool. In Afghanistan, for example, there are at least 10 times as many militant groups today as there were in 2001. Meanwhile, research has consistently shown that military action is rarely effective in shutting down militant “terrorist” groups. Responding to the attacks of 9/11 with what has now been an endless global war has been one of the most catastrophic and deadly mistakes in world history.

Esreteip

In antwoord op de vraag naar de opmerkelijkste naam in de Nederlandse literatuur zou het werk van Bordewijk ongetwijfeld vaak genoemd worden. Alleen Bint (1934) al biedt een hele rij memorabele namen, zoals Whimpysinger, Van der Karbargenbonk en Taas Daamde, Surdie Finnis, Schattenkeinder, Bolmikolke, Klotterbooke en Kiekertak, namen die hij overigens gewoon in het telefoonboek van Rotterdam gevonden had. Of Karakter (1938), met zijn namen van gewapend beton: Dreverhaven, Katadreuffe en Kalvelage.

In antwoord op de vraag naar de opmerkelijkste naam in de Nederlandse literatuur zou het werk van Bordewijk ongetwijfeld vaak genoemd worden. Alleen Bint (1934) al biedt een hele rij memorabele namen, zoals Whimpysinger, Van der Karbargenbonk en Taas Daamde, Surdie Finnis, Schattenkeinder, Bolmikolke, Klotterbooke en Kiekertak, namen die hij overigens gewoon in het telefoonboek van Rotterdam gevonden had. Of Karakter (1938), met zijn namen van gewapend beton: Dreverhaven, Katadreuffe en Kalvelage.

Hoog op mijn lijst zou Inigo Wintrop staan, de hoofdfiguur in Cees Nootebooms roman Rituelen (1980). Een intrigerende naam: welluidend, ongebruikelijk, on-Nederlands en toch ook niet gemakkelijk aan een andere taal te verbinden. Zijn roepnaam – Inni – is een palindroom. Maar hij zou niet op de eerste plaats staan. Die is voor Esreteip. Niet zozeer omdat dat de merkwaardigste, onbegrijpelijkste, vreemdste of gewrongenste is, maar omdat die naam in slechts acht letters een paar eeuwen cultuurpolitiek, koloniaal beleid en calvinistische hypocrisie oproept.

Het was algemeen bekend dat veel van de heren die in “Nederlandsch-Indië” het vaderlands gezag vertegenwoordigden, er een of meer inlandse vrouw(en) op na hielden: een bijzit, een snaar, een njai. Het was evenzeer bekend dat uit zulke relaties vaak kinderen voortkwamen. Nu waren de Nederlandse verwekkers meestal niet zeer geneigd hun snaar te trouwen of, als ze zelf al deugdzaam, dat wil zeggen met een Nederlandse vrouw, getrouwd waren, het kind als het hunne te erkennen. Maar wel ontstond de gewoonte om de bloedband met het kind aan te geven, zeker als het een jongen was. Dat gebeurde vaak door het kind bij de Burgerlijke Stand te laten inschrijven, niet onder de naam van de vader maar onder de omgekeerde versie daarvan. Zo ontstonden bijvoorbeeld de naam Redlum, Reyem of Rhemrev. En Esreteip.

Dat verschijnsel is onomwonden vastgelegd in het werk van de chroniqueur van Nederlands-Indië bij uitstek, P.A. Daum (1850-1898). Twee duidelijke voorbeelden zijn te vinden in de roman Nummer Elf (1895). Op bladzijde 8 wordt een jonge Indo-vrouw geïntroduceerd:

Er ging een deur open, en om de hoek keek een mooi donker kopje met een overvloed van donkere krulletjes op het voorhoofd, grote schitterende zwarte ogen, en een vrolijk lachende mond met parelwitte tanden. ’t Was Ypsilante Nesnaj wier militaire vader haar zijn omgekeerde geslachtsnaam had gegeven en de malle voornaam, die hij had gelezen in een boek over een Griekse prins.

Twee pagina’s verder richt de Nederlandse hoofdpersoon, Vermey, zich tot een klerk ofwel, in Daums woorden, ‘een kopiist’:

Hij liet een kopiist roepen, een broodmagere, grauwbruine jongeman; een dier Indo-europeanen die nooit transpireren en altijd koude handen hebben, maar meestal slim genoeg zijn.

‘Esreteip,’ zei Vermey (’s mans grootvader had Pieterse geheten), je weet dat het vandaag de veertiende is.’

‘Ja meneer’.

Dat Daum deze namen gebruikt en er ter plekke een toelichting bij geeft, illustreert dat daarmee geen grote geheimen verklapt worden. Iedereen wist dat het gebeurde, iedereen kende er in eigen familie- of vriendenkring voorbeelden van, maar er hardop over praten deed men niet.

De naam Esreteip bestaat overigens wel degelijk: een aantal kabinetten geleden, bijvoorbeeld, kende Suriname een minister Esreteip. Waarmee tevens geïllustreerd is, dat dit gebruik niet alleen in Oost-Indië, maar ook in Suriname en op de Nederlandse Antillen voorgekomen zal zijn.

Soms leende een naam zich nog slechter voor omdraaiing dan Vermehr of Pieterse. Als het resultaat echt onuitspreekbaar dreigde te worden, kon er nog altijd een anagram van gemaakt worden: Sermham uit Harmsen of Served uit De Vries. Of het eerste stukje werd er achteraan geplakt: datzelfde De Vries werd dan Vriesde, een naam die in het betaald voetbal (bij F.C. Den Haag speelden twee broers met die naam) en in de damesatletiek (bij de Surinaamse atlete Laetitia Vriesde) was aan te treffen.

Een nog indirectere vorm van erkenning was het kind opzadelen met de naam van de plaats waar de vader vandaan kwam, maar ook dan in omgekeerde vorm. Het telefoonboek van Amsterdam telde lange tijd nog steeds twee nummers op de naam Madretsma. Ook Madrettor bestaat.

De groei van deze groep namen werd ook beïnvloed door de dragers van die namen zelf.

Generaties lang hadden Nederlandse vaders hun trots over hun bij een bijzit verwekt nageslacht geuit in een omdraaiing van de feiten, maar de kinderen zelf wensten er soms zelf ook wel iets in te zeggen hebben. Zij hadden niet iets te verbergen, integendeel, zij waren deels van Europese afkomst en waren daar trots op. En om dat te laten blijken, draaiden zij hun naam weer om en voegden die toe aan wat er al stond. Riemer Reinsma geeft in zijn boekje Aangenaam. Mag ik mij voorstellen? (Amsterdam, 1986) de voorbeelden Redlod van Dolder en Satoor de Rootas.

Wellicht vleit u zich met de gedachte dat het u onmiddellijk zou opvallen als u een zo opmerkelijke naam als Madretsma of Esreteip onder ogen zou krijgen. Maar ons waarnemingsvermogen heeft een flinke marge ingebouwd en iets moet er wel heel erg uitspringen, willen wij het als afwijking van een norm opmerken. Vrijwel dagelijks komen we namen tegen (althans, kunnen we namen tegenkomen) die volgens het hierboven beschreven procédé ontstaan zijn.

In de zo mediterraan ogende achternaam van Jack Gadella, tekstschrijver van een aantal nummers voor ‘Kinderen voor kinderen’, vinden we het woord ‘alledag’ terug. De Vlaamse actrice Alida Neslo is van Surinaamse afkomst. ‘Olsen’ klinkt weliswaar Scandinavisch maar is wel een veel logischer volgorde van letters dan Neslo. De naam van Surinames eerste Olympisch en wereldkampioen zwemmen, Anthony Nesty, heeft eenzelfde constructie. Een bekend Nederlands jazzmuzicus is Rob Essed, een Volkskrant-redactrice heet Yvonne van Gnirrep .

Een koloniaal verleden leeft niet alleen voort in de geschiedenisboeken en in het slechte geweten van een natie, maar ook in de kleine details van alledag.

Voor wie er oog voor heeft.

–

Robert-Henk Zuidinga (1949) studeerde Nederlandse en Engelse Moderne Letterkunde aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam. Hij schrijft over literatuur, taal- en bij uitzondering – over film.

De drie delen Dit staat er bevatten de, volgens zijn eigen omschrijving, journalistieke nalatenschap van Zuidinga. De boeken zijn in eigen beheer uitgegeven. Belangstelling? Stuur een berichtje naar: info@rozenbergquarterly.com– wij sturen uw bericht door naar de auteur.

Dit staat er 1. Columns over taal en literatuur. Haarlem 2016. ISBN 9789492563040

Dit staat er II, Artikelen en interviews over literatuur. Haarlem 2017. ISBN 9789492563248

Dit staat er III. Bijnamen en Nederlied. Buitenlied en film, Haarlem 2019. ISBN 97894925636637

Noam Chomsky: Trump Is Willing To Dismantle Democracy To Hold On To Power

While it’s still too early to predict the likely outcome of the November 2020 presidential election, Donald Trump continues to fall behind in national polls while pulling dirty electoral tricks in the hope of defeating Democratic challenger Joe Biden. Much of Trump’s hope for victory rests with his “law and order” campaign, which promotes lies about mail-in-voting fraud in order to preemptively discredit the election results if they are in Biden’s favor. In this exclusive interview for Truthout, Noam Chomsky discusses the national and international significance of Trump’s refusal to commit to a “peaceful transition to power” and his reliance on conspiracy theories.

C.J. Polychroniou: Noam, with slightly more than two weeks away from the most important national elections in recent U.S. history, Trump’s campaign continues to harp on the message of “law and order” — a political tactic that authoritarian leaders have always relied on in order to control people and to strengthen their grip on a country — but refuses to accept a “peaceful transition to power” if he loses to Biden. Your thoughts on these matters?

Noam Chomsky: The “law and order” appeal is normal, virtually reflexive. Trump’s threat to refuse to accept the result of the election is not. It is something new in stable parliamentary democracies.

The fact that this contingency is even being discussed reveals how effective the Trump wrecking ball has been in undermining formal democracy. We may recall that Richard Nixon, not exactly revered for his integrity, had some reason to suppose that victory in the 1960 election had been stolen from him by Democratic Party machinations. He did not challenge the results, placing the welfare of the country above personal ambition. Al Gore did the same in 2020. The idea of Trump placing anything above his personal ambition — even caring about the welfare of the country — is too ludicrous to discuss.

James Madison once said that liberty is not protected by “parchment barriers” — words on paper. Rather, constitutional orders presuppose good faith and some commitment, however limited, to the common good. When that is gone, we’ve moved to a different sociopolitical world.

Trump’s threats are taken quite seriously, not only in extensive commentary in mainstream media and journals, but even within the military — which might be compelled to intervene, as in the tinpot dictatorships that are Trump’s model. A striking example is an open letter to the country’s highest ranking military officer, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs General Mark Milley, from two highly regarded retired military commanders, Lt. Colonels John Nagl and Paul Yingling. They warn Milley: “The president of the United States is actively subverting our electoral system, threatening to remain in office in defiance of our Constitution. In a few months’ time, you may have to choose between defying a lawless president or betraying your Constitutional oath” to defend the Constitution against all enemies, “foreign and domestic.”

The enemy today is domestic: a “lawless president,” Nagl and Yingling continue, who “is assembling a private army capable of thwarting not only the will of the electorate but also the capacities of ordinary law enforcement. When these forces collide on January 20, 2021, the U.S. military will be the only institution capable of upholding our Constitutional order.”

With Senate Republicans “reduced to supplicant status,” having abandoned any lingering shreds of integrity, General Milley should be prepared to send a brigade of the 82nd Airborne to disperse Trump’s “little green men,” Nagl and Yingling advise. “Should you remain silent, you will be complicit in a coup d’état.”

Hard to believe, but the very fact that such thoughts are voiced by sober and respected voices, and echoed throughout the mainstream, is reason enough to be deeply concerned about the prospects for U.S. society. I rarely quote New York Times senior correspondent Thomas Friedman, but when he asks whether this might be our last democratic election, he is not joining us “wild men in the wings” — to quote McGeorge Bundy’s term for those who don’t automatically conform to approved doctrine.

Meanwhile, we should not overlook how leading elements of Trump’s “private army” are showing their mettle in their usual terrain of deployment: the cruel Arizona desert to which the U.S., since Clinton, has driven miserable people fleeing from our destruction of their countries so that we may evade our responsibility — both legal and moral — to offer them an opportunity for asylum.

When Trump decided to terrorize Portland, Oregon, he didn’t send the military, probably expecting that it would refuse to follow his orders, as had just happened in Washington, D.C. He sent paramilitaries, the most fierce of them the tactical unit BORTAC of the Border Patrol, which is given virtually free rein with the “damned of the earth” as its targets.

Immediately on returning from carrying out Trump’s orders in Portland, BORTAC returned to its regular pastimes, smashing up a flimsy medical aid center in the desert where volunteers seek to provide some medical aid, even water, to desperate people who managed somehow to survive.