Ardhakathanak: A Commoner’s Discovery Of The Mughal Milieu

Abstract

The Ardhakathanak by Banarasidas is often considered the first autobiography in Hindi. Completed in the year 1641, the book provides us with a commoner’s understanding of the Mughal world. Often subjected an imperial bias, the book is a wildly neglected source of history. The study attempts to highlight various societal norms and ethics as evidenced by the Ardhakathanak. It undertakes a thematic division in understanding medieval Indian society, focusing on merchant practices, societal norms and Jain religion. Various aspects of a middle class man’s life are unraveled through the course of this study, including education, business decisions, wealth, family, domesticity, religious assimilation, rationality and self-discovery.

The study also embarks on an analysis of the Varanasiya sect of Jain religion briefly. Finally, emerging trends of individuality are highlighted. The study culminates with a brief account of how underutilized this primary source remains despite obvious merits to it.

Keywords: Banarasidas, Ardhkathanak, autobiography, merchant practices, religious pursuits, cultural history.

1. Introduction

The development of the literary genre of autobiography is a fairly ancient one, with St. Augustine’s autobiographical work ‘Confessions’ written in 399 CE. However, the understanding of the term autobiography to be a form of ‘self life writing’ is a recent phenomenon. The Oxford English Dictionary credits Robert Southy to be the progenitor of autobiography in the year 1809. However we find a reference to autobiography or self-biography being used by William Taylor in the Monthly Review of 1797.[i]The motivations for committing one’s life to writing are often religious in nature, to record stages in an individual’s life by which they lose their own identity to celebrate God’s divine power.[ii] Today, these works have become a prominent source of history and are extensively researched to arrive at a deeper understanding of the period it was written in. The earliest known biographical work that was produced in India is the Harshacharita written by Banabhatta in the 7 th century CE. However, truly autobiographical accounts only appear in India with the advent of Mughals. Among these, Baburnama was the earliest, and records Babur’s life between 1483 to 1530.[iii] The autobiographies written during this period were meant to preserve a person’s family history and good deeds for posterity. Thus, the representation of the subject is in light of the reader’s judgement. Therefore, we may conclude that these writings often lack a humanizing touch that can relate the subject to the reader.

One such piece in the ocean of Mughal writings is Banarasidas’s Ardhakathanak. It was first discovered by Nagari Pracharini Sabha and published by Dr. Mataprasad Gupta in 1943.[iv]

Banarasidas was a Jain merchant who lived during the Mughal Era in India. The title of his autobiography translates to ‘half a tale’. The book was completed in the winter of 1641 in the imperial capital of Agra, when Banarasi was 55 years of age. In Jain philosophy, a full life is considered to be of one hundred and ten years. Thus, the title of Banarasi’s book ‘Half a Tale.’ Although, the tale began to be the story of half a life, Banarasi met his demise only two years after the completion of his book, implying that the story covered his entire life. Written in the language of the Indian heartland, Braj Bhasha. Ardhakathanak is considered to be the first autobiography in Hindi.[v] Much to the contrary to other Mughal works, Banarasidas’s tone throughout the book is that of unabashed candor. Over the course of the book, Banarasi establishes a rapport with the reader and slowly but surely becomes a friend. By the time, we reach Banarasi’s close of life, a feeling of a long and fruitful companionship lingers on with the reader. We know Banarasi’s secrets, sorrows and soaring moments. Unlike other autobiographical works of the contemporary period the emphasis is not on making a perfect man devoid of any flaws, fit to govern the territory of India, but to lay bare before the reader the heart and soul of subject, good or bad.

It is evident from the content of the book and style of writing that Banarasi did not expect his autobiography to be read nearly 400 years later. In fact, there was an understanding that it would only be read by limited audience of friends and kinsmen.[vi] In Banarasi’s own words, the only reason he ventured into the business of recording his life, is ‘let me tell you all my story’.

A Jain from the noble Shrimal family,

That prince among men, that man called Banarasi,

He thought to himself, let me tell my story to all [vii]

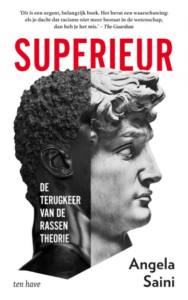

Angela Saini – Superieur. De terugkeer van de Rassentheorie

Superieur van de wetenschapsjournalist Angela Saini is een verslag van het uitgebreide onderzoek naar de biologische feiten rondom het begrip ras.

Bestaat er een verband tussen ras en IQ? Welk ras is het beste? Zijn wij één mensensoort of niet? Wat kan het moderne wetenschappelijke bewijsmateriaal ons echt vertellen over de menselijke verschillen, en wat betekenen die vervolgens?

Deze vragen zijn allerminst gedateerd. De rassentheorie beleeft een zorgwekkende comeback, in wetenschap en politiek. Angela Saini onderzoekt in Superieur pseudowetenschappelijk beweringen en theorieën over ras, en toont aan waarom ze onhoudbaar zijn. Angela Saini komt tot de conclusie dat de biologie deze vraag niet kan beantwoorden. Als we de betekenis van ras willen begrijpen, moeten wij begrijpen hoe macht werkt. Een onderzoek van de Verlichting via het negentiende-eeuwse imperialisme en de twintigste-eeuwse eugenetica naar de revival van de rassentheorie in de eenentwintigste eeuw.

Saini toont in Superieur aan hoe macht het idee van ras telkens weer opnieuw vormgeeft, hoe macht de wetenschappelijke feiten beïnvloedt. De betekenis houdt verband met de tijd.

Lang hebben witte mensen van Europese afkomst zich aan de top van de machtshiërarchie bevonden en bouwden hun wetenschappelijk verhaal over de menselijke soort rond dit geloof. Maar geen enkele regio of volk heeft recht op een claim op superioriteit.

‘Ras is het tegenargument. Ras komt in de kern van de zaak neer op het geloof dat we van geboorte anders zijn, diep in ons lichaam, misschien zelfs qua karakter en intellect, en in onze uiterlijke verschijning.’ Het is het idee dat bepaalde groepen mensen bepaalde aangeboren kwaliteiten hebben. Ras, gevormd door macht, heeft een eigen kracht verkregen. Witheid werd de zichtbare maatstaf van de menselijke moraliteit. Sinds de Verlichting hadden veel Europese denkers zich verenigd rond het idee dat de mensheid één was, dat we dezelfde gemeenschappelijke vermogens deelden. Ook al was er een rassenhiërarchie, ook al waren er mindere mensen en betere mensen, we waren allemaal nog steeds menselijk. In de volgende eeuw vroeg men zich weer af, of we echt wel tot hetzelfde soort behoorden: want waarom zagen wij er niet hetzelfde uit en gedroegen we ons niet op dezelfde manier? Het is geen toeval dat de moderne ideeën over ras zijn gevormd tijdens de hoogtijdagen van het Europese kolonialisme, toen de machthebbers overtuigd waren van hun eigen superioriteit. In de VS werd dezelfde verwrongen logica gebruikt om de slavernij te rechtvaardigen. En de wetenschap voorzag het racisme van intellectueel gezag.

De rassentheorie heeft zich altijd op het kruispunt van wetenschap en politiek opgehouden, en van wetenschap en economie. Ras was niet alleen een middel om fysieke verschillen te classificeren, het was ook een manier om de menselijke vooruitgang te meten, en om te kunnen oordelen over de capaciteiten en rechten van anderen, aldus Saini. Ook Hitlers ideologie van rassenhygiëne had geen kans van slagen zonder wetenschappers, zij zorgden voor het theoretisch kader en droegen bij aan het klaren van de klus zelf. Degenen wier ideeën het regime goed te pas kwamen werden gepromoot en gevierd.

In 1950 formuleerde UNESCO, vlak na de Tweede Wereldoorlog, zijn eerste verklaring over ras, waarin de eenheid tussen mensen werd benadrukt in een gezamenlijke inspanning om een einde te maken aan wat wordt gezien als het gevolg van een ‘fundamenteel anti-rationeel denksysteem.’ Alle mensen behoren tot dezelfde soort ‘Homo sapiens’. Het grootste deel van de zichtbare diversiteit is cultureel van aard. Een cruciaal moment in de geschiedenis. Racisme was niet langer aanvaardbaar. Wetenschappers en antropologen gingen grotendeels achter UNESCO staan.

We denken dat de verschrikkingen van de Holocaust en eerdere genocides, de slavernij en het kolonialisme tot een andere tijd behoren. Dat eugenetica een vies woord is. Saini definieert eugenetica als is een berekende manier van denken over het menselijk leven; mensen worden gereduceerd tot louter delen van een geheel, die hun ras omlaag- of omhoogtrekken. Bijna alles wat we zijn is al beslist voordat we geboren zijn. Maar er zijn weer nieuw wegen gevonden om raciale verschillen te onderzoeken, en dat sommige rassen iets beter waren dan de andere. Na de Tweede Wereldoorlog hebben intellectuele racisten nieuwe netwerken opgezet met het doel racisme weer respectabel te maken. De eugenetici en rassentheorie waren niet verdwenen met de ondergang van het naziregime. Ras werd herpositioneerd voor de eenentwintigste eeuw. Ze noemt als een van de voorbeelden de Indiase regering, die in 2018 een commissie in het leven had geroepen om de geschiedenis te herschrijven. Een mythische versie van de geschiedenis zou worden gepropageerd waar in Indiase dominante geloof, het hindoeïsme, in het hele Indiase verleden centraal zou worden gesteld.

We denken dat de verschrikkingen van de Holocaust en eerdere genocides, de slavernij en het kolonialisme tot een andere tijd behoren. Dat eugenetica een vies woord is. Saini definieert eugenetica als is een berekende manier van denken over het menselijk leven; mensen worden gereduceerd tot louter delen van een geheel, die hun ras omlaag- of omhoogtrekken. Bijna alles wat we zijn is al beslist voordat we geboren zijn. Maar er zijn weer nieuw wegen gevonden om raciale verschillen te onderzoeken, en dat sommige rassen iets beter waren dan de andere. Na de Tweede Wereldoorlog hebben intellectuele racisten nieuwe netwerken opgezet met het doel racisme weer respectabel te maken. De eugenetici en rassentheorie waren niet verdwenen met de ondergang van het naziregime. Ras werd herpositioneerd voor de eenentwintigste eeuw. Ze noemt als een van de voorbeelden de Indiase regering, die in 2018 een commissie in het leven had geroepen om de geschiedenis te herschrijven. Een mythische versie van de geschiedenis zou worden gepropageerd waar in Indiase dominante geloof, het hindoeïsme, in het hele Indiase verleden centraal zou worden gesteld.

De hindoe-superioriteit zou sommige Indiërs de kans bieden hun zelfrespect terug te winnen, collectieve trots te laten gelden, en een nieuw gevoel van nationale identiteit bouwen.

We blijven steeds maar terugkomen op ras omdat we er vertrouwd mee zijn. Onze moderne ideeën over ras zijn nauw verbonden met hoe we eruitzien. In biologische termen lijken echter de verschillen niet verder te gaan dan de huid. Het is een vergissing te denken dat de interne verschillen even groot zijn als de externe verschillen lijken. De opkomst van nationalisme en racisme heeft velen van ons verrast. Identiteitspolitiek heeft velen in de greep. Het doel is hetzelfde: het benadrukken van de verschillen ten bate van politiek gewin.

Zij doet geen beroep een gedeelde menselijkheid. Alles om maar ‘superieur’ te zijn.

Angela Saini – Superieur. De terugkeer van de Rassentheorie. Uitgeverij Ten Have, Amsterdam, 2020. ISBN 9789025907174

Angela Saini is wetenschapsjournalist voor BBC Radio. Haar werk is onder andere gepubliceerd in New Scientist en The Economist.

Eerder verscheen bij Uitgeverij Ten Have Ondergeschikt: Hoe kennis over vrouwen ons misleidt en wat we daaraan kunnen doen.

Linda Bouws – St. Metropool Internationale Kunstprojecten

Anaclept en cento: de kunst van het herdichten

Buiten de limerick en het sonnet, het ollekebolleke en het Sinterklaasgedicht kent de letterkunde nog veel meer versvormen, waarvan de meeste zich verborgen houden in de nevelen der eeuwigheid.

Een ondergewaardeerd genre is het herdichten. Sommige dichters hebben namelijk niet genoeg aan hun eigen werk, maar vieren hun inspiratie ook bot op andermans verzen, niet zelden zo intensief dat dat hele bundels vol persiflages en parodieën, parafrases en pastiches opgeleverd heeft. Drs. P vulde, als Coos Neetebeem, de bundel Antarctica (’s-Gravenhage, 1980), waarin hij bijvoorbeeld de kern van Willem Kloos’ bekendste sonnet terugbracht tot

Ik ben een God in`t diepst van mijn gedachten

En zit in’t binnenst van mijn ziel ten troon

Maar verder ben ik helemaal gewoon

Met haaruitval en spijsverteringsklachten

en die van A.C.W. Starings’ Oogstlied (‘Sikkels klinken; Sikkels blinken; Ruisend valt het graan. Zie de bindster garen! Zie, in lange scharen, Garf bij garven staan!) tot

Sikkels klinken

Sikkels blinken

Ruisend valt het graan

Als je iemand weg ziet hinken

heeft hij’t fout gedaan

Gerrit Komrij publiceerde een bundel met de alleszeggende titel Onherstelbaar verbeterd (Amsterdam, 1981), waarin hij een aantal gedichten compleet herschreef. ‘De Dapperstraat’ van J.C. Bloem, althans het eerste kwatrijn daarvan,

Natuur is voor tevredenen en legen.

En dan: wat is natuur nog in dit land?

Een stukje bos, ter grootte van een krant,

Een heuvel met wat villaatjes ertegen.

werd bij Komrij

De Kalverstraat

Cultuur is om m’n reet mee af te vegen.

En dan: wat is cultuur nog in dit land?

Een steekje los, een stukje in de krant,

Gekeuvel met wat prietpraatjes ertegen.

If Trump Had Followed Vietnam’s Lead On COVID, US Would Have Fewer Than 100 Dead

As the coronavirus pandemic rages on, exposing to the fullest the glaring weakness of our inequitable health system, and as the unemployment situation goes largely unaddressed, it’s becoming more than obvious that the U.S. is in dire need of fixing. An advanced social welfare state, with a full employment agenda, is the way out, argues world-renowned progressive economist Robert Pollin in this exclusive interview with Truthout. Pollin is distinguished professor of economics and co-director of the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, and co-author (with Noam Chomsky and me) of the forthcoming book The Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet.

C.J. Polychroniou: Bob, the coronavirus crisis is wreaking havoc on the economy, but it has also revealed how poorly equipped the United States is in dealing with major economic crises. In fact, as economist Joseph Stiglitz has pointed out, “We built an economy with no shock absorbers.” With that in mind, and with millions of Americans unemployed and even struggling to meet basic needs, can you offer us a straightforward assessment of the Trump administration’s economic response to the coronavirus crisis?

Robert Pollin: The short answer is unequivocal: The Trump administration’s response has been nothing short of disastrous. Let’s begin with figures on lives that have been needlessly lost in the U.S. due to Trump’s toxic combination of indifference, hostility to science, and racism. As of August 17, we are approaching 170,000 deaths from COVID in the U.S., more than triple the total U.S. death toll from fighting in Vietnam. We have no evidence that the death rate will be declining significantly anytime soon. This level of U.S. deaths from COVID amounts to 514 per 1 million people. By comparison, Canada’s death rate is less than half that of the U.S., at around 239 deaths per million, even while Canada itself is also a relatively poor performer. Germany’s death rate, at 110 per million, is 80 percent lower than the U.S., but Germany is still only a middling performer. Among the strong performers, the death rates are 15 per million in Australia, 9 per million in Japan, 6 per million in South Korea and 3 per million in China, even though the virus first emerged in China. If the U.S. had managed the COVID pandemic at the level of, say, Australia, fewer than 5,000 people would have died as of today as opposed to nearly 170,000.

Vietnam is the most extraordinary case. It has experienced a total of 22 deaths in a country of 95 million people, which amounts to a death rate of 0.25 per million. This is for a country in which the average per capita income is about 3 percent of that in the U.S. It is also a country, of course, that U.S. imperialists tried to destroy a generation ago. If the U.S. had handled COVID at Vietnam’s level of competence over the past eight months, then fewer than 100 U.S. residents in total would be dead today from the pandemic.

In terms of managing the pandemic-induced economic collapse, the massive $2 trillion (10 percent of U.S. GDP) stimulus program that Congress passed and Trump signed in March, the CARES Act, did provide substantial support for unemployed workers. Fifty-six million people — 35 percent of the entire U.S. labor force — filed unemployment claims between March and August. For the most part, they all received $600 per week in supplemental support, which more than doubled what most would have received otherwise.

The CARES Act did also deliver huge bailouts for big corporations and Wall Street. Adding everything up, it was clear even at the time of passage that the CARES Act was not close to meeting the magnitude of the oncoming crisis. Among other features, it provided only minimal support for hospitals on the front lines fighting the pandemic, and even less support for state and local governments. The Upjohn Institute economist Timothy Bartik estimates that state and local governments are staring at upward of $1 trillion in budget shortfalls through the end of 2021, equal to between 20-25 percent of their entire budgets. If these budget gaps are not filled in short order, we will begin to see mass layoffs of nurses, teachers, school custodians and firefighters. Of course, these budget cuts will only spread and deepen the ongoing economic crisis.

The Democratic majority in the House of Representatives did pass a second, and even larger, $3 trillion stimulus measure, the HEROES Act, back in May. It included $1 trillion in support for state and local governments. But Trump and the Senate Republican majority have blocked action on this for the past three months. Meanwhile, 16 million workers have now lost their $600 per week in supplemental benefits and state and local governments are teetering on collapse. Trump appears to want to make unemployed workers and public sector programs starve, perhaps so he can appear to swoop in and bail them out right before November’s election. Trump has held out a “compromise” proposal with Democrats. This would feature a payroll tax cut that would permanently decimate Social Security and Medicare. Trump also wants any new stimulus program to also incorporate his current top priority, which is to destroy the U.S. Postal Service in time to prevent people from voting against him through mail balloting.

Définir l’islamophobie et ses manifestations politiques après les attentats de « Charlie Hebdo »

Résumé

Cet article examine les difficultés rencontrées par les définitions contemporaines de l’islamophobie, notamment celle de l’influent rapport Runnymede, face aux réactions des responsables politiques européens aux attentats de janvier 2015 à Paris. L’application de la méthode d’analyse du discours politique (ADP) à ces réactions souligne leur ambiguïté eu égard aux définitions contemporaines de l’islamophobie, et justifie de les affiner.

Mots clés

Islamophobie, rapport Runnymede, attentats de Charlie Hebdo, Union européenne, populisme.

Cet article est la version traduite et condensée de: Bogacki Mariusz, de Ruiter Jan Jaap et Sèze Romain, Defining Islamophobia and its socio-political applications in the light of Charlie Hebdo attacks in Paris, Rozenberg Quartely, 2019. URL:

http://rozenbergquarterly.com/the-charlie-hebdo-attacks-in-paris-defining-islamophobia-and-its-socio-political-applications/

Introduction

L’étude des réactions de peur ou d’hostilité à l’égard de l’islam et des musulmans a connu un tournant avec la publication du rapport Islamophobia : a challenge for us all (Runnymede Trust, 1997 et 2016), par la Commission on British Muslims and Islamophobia, créée par le Runnymede Trust (groupe de réflexion indépendant). Cette étude pionnière propose d’identifier les causes et manifestations de l’islamophobie, définie comme « une hostilité non fondée envers l’islam », une « crainte ou [une] haine de l’islam, et donc […] la peur ou l’aversion des musulmans ou de la plupart d’entre eux » (Runnymede Trust, 1997, 1), et les « conséquences d’une telle hostilité en matière de discriminations […] et d’exclusion des activités politiques et sociales » (idem, 4). Les auteurs opèrent cependant une distinction fondamentale entre « la peur phobique de l’islam [qui] caractérise des attitudes fermées, et les désaccords et critiques légitimes [qui] caractérisent des attitudes ouvertes » (idem, 4). Cette distinction repose sur huit clivages dans la façon d’appréhender l’islam et les musulmans : uniformité/diversité, séparation/interaction, infériorité/différence, adversité/partenariat, manipulation/sincérité, rejet/considération de la critique de l’Occident, justification/réprobation des discriminations, justification/réprobation de l’islamophobie (idem : 5).

Bien que ce rapport demeure une référence, il a commencé à être vigoureusement critiqué dix ans après sa publication, en particulier pour cette distinction entre « attitudes fermées » et « ouvertes ». Cette binarité tend à résumer l’attitude envers l’islam et les musulmans à de l’islamophilie ou à de l’islamophobie, tout en objectivant par effet de miroir des représentations symétriquement opposées de musulmans « bons ou mauvais », quoiqu’il en soit essentialisés, (Allen, 2010, 76). « L’islamophobie ne peut être déterminée et définie par le “type” de musulmans qui en sont victimes. Elle doit aller plus loin et tenir compte de la reconnaissance d’un “caractère musulman” réel ou perçu », car cette approche réduit l’islamophobie à un « phénomène à la fois trop simpliste et largement superficiel, défini davantage par les caractéristiques des victimes que par la motivation et les intentions des auteurs » (idem, 79-80). Or, cette approche néglige ce faisant l’existence d’un angle mort : il existe en effet des préjugés qui ne procèdent pas d’attitudes « fermées », mais qui sont la conséquence de différences de cultures, de représentations du monde et de valeurs. Les musulmans qui ne se laissent pas réduire à cette binarité sont ainsi exclus de ce traitement de l’islamophobie, et peuvent de ce fait devenir les victimes oubliées du phénomène.

Les analyses de Chris Allen invitent à considérer de nouveaux aspects des manifestations de l’islamophobie, toujours plus ambigus et complexes après le 11 Septembre, comme l’illustrent les débats contemporains sur le niqab, le multiculturalisme et les processus d’intégration religieuse et culturelle en Europe. À sa suite, divers chercheurs ont alors souligné les limites du rapport Runnymede, et proposé des alternatives. Deepa Kumar (2012, 2) et Ibrahim Kalin (2011, 11) se concentrent davantage sur la dimension racialisante du phénomène. Tahir Abbas (2011, 65), Nathan Lean et John Esposito (2012, 13) en analysent les aspects phobiques. Mohamed Nimer (2011, 78), Hedvig Ekerwald (2011) et Tahir Abbas (2011) s’intéressent aux caractéristiques culturelles et religieuses de l’islamophobie. Même Chris Allen (2010, 190) a tenté de proposer une définition alternative qui, si exhaustive soit-elle, présente une longueur et des incohérences telles qu’elle s’avère peu opérationnelle. Jocelyne Césari (2011) est sans doute celle qui acte le plus précisément ces difficultés. Elle souligne que le terme « islamophobie » est contestable parce qu’il est souvent « appliqué de manière imprécise à des phénomènes divers, allant de la xénophobie à l’antiterrorisme. Il regroupe toutes sortes de discours et d’actes en suggérant qu’ils émanent tous d’un même noyau idéologique, issu d’une peur irrationnelle (phobie) de l’islam » (idem, 21). C’est donc l’ambiguïté du terme permise par sa généralité qui rend impossible son application aux phénomènes divers qui peuvent naître des préjugés à l’égard de l’islam, mêlant préjugés et idéologies politiques variées.

Ces débats ont justifié une actualisation du rapport Runnymede, vingt ans après sa publication en 1997, dans l’objectif « d’améliorer la précision et la qualité des débats, ainsi que des politiques publiques pour lutter contre l’islamophobie » (Elahi, Khan, 2017, 1). Sur la base des réactions au rapport Runnymede, le groupe de réflexion en propose deux nouvelles définitions. La première, abrégée, définit l’islamophobie comme un « racisme antimusulman ». La seconde, plus détaillée, la définit comme « toute distinction, exclusion, restriction ou préférence à l’égard des musulmans (ou perçus comme tels) qui a pour objet ou pour effet d’annuler ou de compromettre la reconnaissance, la jouissance ou l’exercice, sur un pied d’égalité, des droits de l’Homme et des libertés fondamentales dans les domaines politique, économique, social, culturel ou tout autre domaine de la vie publique » (ibid.). Certains contributeurs à ce rapport ont également questionné la pertinence du terme « islamophobie ».

Après avoir discuté de notions de « racisme antimusulman », « préjugés antimusulmans » et « discriminations antimusulmans », Shenaz Bunglawala conclut à la nécessité de conserver le terme « islamophobie » pour deux raisons. Premièrement, il ressort des contenus médiatiques (britanniques) que le terme « islam » a plus souvent une charge péjorative que le terme « musulman », « plaçant ainsi l’appartenance perçue à un groupe au cœur de ces stéréotypes » (Bunglawala, 2017, 70). Deuxièmement, « adopter une terminologie centrée sur la victime (i.e. sur le « musulman » et non sur « l’islam ») risquerait de mener la lutte contre l’islamophobie à manquer sa cible et à oublier de prendre en considération le contexte favorable à l’uniformisation des représentations sur l’islam et les musulmans ». À revers des autres contributeurs, Shenaz Bunglawala argue en faveur de la pertinence de la dichotomie opposant attitudes « ouvertes » et « fermées », notamment au regard de la définition de l’islamophobie comme « racisme antimusulman » : « à une époque où les termes “islam”, “islamique”, “islamiste extrémiste” et “islamiste” sont fréquemment chargés de connotations péjoratives, est-il si étonnant que “l’islamophobie” conserve son pouvoir de nommer l’objet de la haine ? » (idem, 72).

Il ressort de ces débats qu’il est nécessaire de se départir des prénotions sur les victimes a priori pour examiner la pertinence des définitions de l’« islamophobie » au regard des manifestations qu’elles recouvrent dans un contexte donné. Sachant qu’elles ont crû tout en se complexifiant après le 11 Septembre, dans quelle mesure la résurgence du djihadisme depuis le milieu des années 2000 en Europe et les réactions qu’elle suscite interrogent-elles la pertinence de ce terme ? Afin d’apporter des éléments de réponse à cette question, seront examinées les réactions des responsables politiques européens à des attentats djihadistes qui les ont récemment tous interpelés : ceux de janvier 2015 à Paris. Ces évènements ont en effet concouru à renforcer les discours et pratiques discriminantes à l’endroit des musulmans dans l’Union européenne (Foundation for Political, Economic and Social Research, 2016), tout particulièrement dans le contexte des débats sur la radicalisation où les populations musulmanes font facilement figure d’ennemi intérieur (Baker-Beall et al., 2015 ; Ragazzi, 2016). Les réactions des responsables politiques à ces attentats sont en effet propres à faire apparaître les ambiguïtés liées à l’appréhension contemporaine de l’islamophobie, donc à inviter à réviser sa définition d’une part, et à réfléchir à ses implications sur les plans politique, législatif et social d’autre part.

Après avoir décrit la méthodologie appliquée pour construire le corpus des discours et les analyser (1), seront présentés les résultats de l’analyse du discours politique (2), avant de conclure par des propositions visant à cerner plus pertinemment les discours discriminatoires à l’endroit de l’islam et des musulmans.

An unhappy childhood: een zoektocht in drie tafereeltjes

In het Bzzlletin-nummer van april 1992 stond een vraaggesprek dat ik had met Adriaan van Dis.(klik hier) Toen ik het onder ogen kreeg, trof mij de allereerste vraag. Die luidde: ‘Als ik Nathan Sid, Zilver of Indische duinen lees, denk ik: Wilde had gelijk toen hij zei An unhappy childhood is a writer’s goldmine. Dat verbaasde me, want ik wist zeker dat in de kopij die ik ingeleverd had, stond: ‘Poe had gelijk…’. Het was immers een uitspraak van Edgar Allan Poe, en die bleek nu door de hoofdredacteur op eigen gezag veranderd.

Om zijn eigenzinnig optreden af te straffen, besloot ik hem meteen de exacte vindplaats in het werk van Poe als bewijs te leveren. Toen ik die na een half uur vruchteloos bladeren nog niet gevonden had, begon mij twijfel te bekruipen. Ik nam het werk van Gerard Reve erbij, want die had deze uitspraak meermalen geciteerd, o.a. in Nader tot U (1966) en Brieven aan Bernard S. (1981), en, meende ik, zelfs eens als motto voor een van zijn romans gebruikt.

Ook dat was verspilde tijd; wel vond ik voorin de roman Oud en eenzaam (1978) het gedicht Alone van Poe, waarvan de eerste woorden luiden: From childhood’s hour I have not been as others were. Dat zal wel de bron van de verwarring geweest zijn.

En toen ik na enig zoeken in het Verzameld Werk van Oscar Wilde – je kunt immers niet weten – ook niets gevonden had, raakte ik stilaan geïrriteerd. Wel vond ik in Reve’s De taal der liefde (1972) op pagina 45 deze passage: ‘Ik werk maar rustig voort. Ik streef naar ongeveer e-e-n hoofdstuk per maand. “All art is quite useless.”’ Dat is een uitspraak van Oscar Wilde, die wellicht voor mijn hoofdredacteur de aanleiding voor zijn ingreep geweest was.

Ik doorzocht elk aforismenboek en elk literair handboek waar ik de hand op kon leggen, maar vond nergens ook maar de geringste aanwijzing. Mijn verbazing nam toe dat dit aforisme, dat mij tamelijk gangbaar leek, in geen enkele citatenbundel te vinden was, Nederlands noch Engels noch Amerikaans.

In hetzelfde Bzzlletin-nummer staat een artikel over het journalistieke werk en de gedichten van Nico Scheepmaker. Een van de aardigste dingen die de journalist Scheepmaker deed, was zich in een vraag vastbijten en niet opgeven voor hij het antwoord gevonden had. In de bundel Het bolletje van IBM (1987), waaraan ik met de dichter-journalist zelf heb mogen werken, staan daarvan een paar goede voorbeelden. Zo zocht hij eens met grote vasthoudendheid naar de maker van een van Neerlands bekendste anonieme verzen, beginnend met

Een mens lijdt dikwijls ‘t meest

Door ‘t Lijden dat hij vreest

Doch dat nooit op komt dagen.

Vergeefs, want hoewel hij iedereen inschakelde die meer dat twee regels poëzie uit het hoofd kende, van Gerrit Komrij tot Garmt Stuiveling, bleef zijn queeste zonder resultaat. Daar liet hij het niet bij zitten: ‘Ik vroeg aan de lezers van mijn dagelijkse Trijfel-column (die immers bij een abonnee-aantal van ruim 900.000 volgens Karel van het Reve & ‘de best geoutilleerde computer van Nederland’ vormen) of ze mij uit de brand konden helpen.’ Hun bereidheid was groot maar de verwarring, om het vervolg kort samen te vatten, werd nog groter..

Het leek mij dan ook geheel in de geest van Nico Scheepmaker mijzelf de taak op te leggen de vindplaats van het gewraakte aforisme te achterhalen. Al snel werd mij een helpende hand toegestoken, want ik was niet de enige die de openingsvraag aan Van Dis met bevreemdinggelezen had. Jan Ypinga uit Arnhem schreef mij een brief, waaruit ik citeer: ‘U schrijft het adagium An unhappy childhood is a writer’s goldmine abusievelijk toe aan Oscar Wilde. Deze, onsterfelijke, regel komt echter uit de koker van Leslie A. Fiedler, en werd in de Nederlandse literatuur dikwijls geciteerd door m.n. Gerard Reve.’