ISSA Proceedings 2006 ~ On How To Get Beyond The Opening Stage

1. Introduction

What is the opening stage? And why would it be hard to get beyond it?

The opening stage – as many will know – is one of the four discussion stages contained in the familiar pragma-dialectical model of critical discussion (Van Eemeren & Grootendorst 1984, 1992, 2004), which constitutes a normative model for argumentative activities aimed at the resolution of a difference of opinion. It is one of the merits of this model that, in its description of the ideal argumentative process, it does not limit itself to argumentation in the proper, but narrow, sense of advancing arguments for a standpoint, but includes discussion stages where other necessary steps for the resolution of differences of opinion are located. Remember that there are just four stages, and that they are, in order, the following:

1. Confrontation Stage

2. Opening Stage

3. Argumentation stage

4. Concluding Stage.

Contrary to what may be expected, the opening stage does not figure as the first stage (whereas the concluding stage finds itself indeed neatly placed at the end). This is a vagary of nomenclature that sometimes breeds confusion even among experts. Apart from that, it is clear that the process of argumentation proper has been placed in the third stage, the argumentation stage, and that the first two stages figure as preparatory stages.

The problem I want to discuss actually pertains to both preparatory stages, namely: how can one get them completed, in a satisfactory way and within a reasonable time, to move on to what is properly called argumentation. However I will discuss this problem with special reference to the opening stage.

To enhance a more lively remembrance of the four stages of discussion you could picture them as a house with four rooms (see Figure 1).

To enhance a more lively remembrance of the four stages of discussion you could picture them as a house with four rooms (see Figure 1).

When guests enter into this house they start on the ground floor in Room 1, a kind of gym – a place suitable for boxing exercises – which represents the confrontation stage, i.e., the stage where a difference of opinion is made explicit. The goal is to get, ultimately, to Room 4, another ground floor room, giving on to the garden, where refreshments are served – drinks and tidbits – which room represents the concluding stage, i.e., the stage where agreements are achieved. Now to get there, our guests have to pass through two other rooms, both on the upper floor, which represent the opening stage (Room 2) and the argumentation stage (Room 3). In Room 3, the actual business of argumentation is going on: for instance, a standpoint S is being supported by argument. But before one gets there, a lot of preparatory work needs to be done. The agenda will be presented in the next section, but one thing that has to be settled is the choice of a system of discussion rules that the parties are going to adhere to. No wonder Room 2 is packed with theorists of argumentation debating these rules. The complexity of issues and the multiplicity of perspectives is making one wonder whether any agreement will ever be reached at all. One would be fortunate to see the people in Room 2 manage to come to an agreement about just the shape of their table. Even that issue can be nasty, as was the case at the opening stage of the Paris Peace Conference about Vietnam. As some will remember, in 1968-69 the shape of the table was debated for months. This, of course, was a case of opening a negotiation dialogue, not a persuasion dialogue or argumentative discussion. Yet, the case of the Paris Peace Conference constitutes a classical illustration of how difficult it may be to get beyond the opening stage of a discussion. (Which is not to say that the issue of the shape of the table was unimportant at the time.)

The rest of this paper will be organized as follows. As I announced before, I shall first present the agenda for Room 2, i.e., a task list for the opening stage, assembled from pragma-dialectic writings (Section 2). Then I shall illustrate these tasks in a dialogue (Section 3), point out some problems (Section 4) and start on some sketch of a way to adapt the architecture of critical discussion in order to overcome these problems (Section 5). Read more

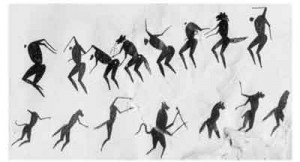

Rock Art Research in South Africa

Therianthropes and trance dance from artwork painted by Kalahari artist, the late Vetkat Regopstaan Kruiper (with permission)

Ethno-archaeology: Oral narratives and rock art

The focus of my research is on the method of recording oral narratives and their link to, and possible use in, the interpretation of rock art, specifically rock engravings. Research on indigenous knowledge and artefacts falls within a contentious area of indigenous archaeology associated with colonialists’ geographic and intellectual imperialism. It is necessary for my contextual approach to include, as in the exploration of myths, the theoretical setting of ethno-archaeology within which my research takes place. In the discipline of archaeology the use of ethnography falls under what Renfrew and Bahn (1991: 339) call ‘What did they think?’ The use of ‘they’ points not only to ethical issues of ‘othering’, the negative artificial construction of two camps of cultures and the corresponding approaches of scholars and present day descendants of the artists, but also to the time gap between the artists of the past and the present (Lewis-Williams & Pearce, 2004).

The rock paintings situated in caves, shelters and on portable stones, mostly in the mountainous regions in South Africa, and rock engravings situated predominantly in the plateau areas, on boulders on hills or near rivers, date mostly from within the last few thousand years. However, small mobiliary painted stones from Apollo 11 Cave and an engraved ochre piece from Blombos Cave date from some 25 000 and up to 70 000 years ago respectively (Lewis-Williams & Pearce, 2004). This considerable antiquity complicates any attempts at interpreting the rock art by way of oral narratives, even those recorded by the earliest colonialists. Furthermore, our views and therefore theories on art, oral narrative and methodology are constantly changing (Bahn, 1998).

Bamanya: Un Livre Dans La Forêt

Si tu tires une croix diagonale sur une carte moderne du monde, tu verras que Mbandaka se trouve au centre. Stanley érigeait ici en 1883, un “outpost of progress” sous le nom d“Equator Station”. Maintenant, Mbandaka (Coquilhatville jusqu’en 1966) est une des plus grandes villes du Congo, avec entre l00.000 et 150.000 habitants. Le bourg à la rive de cette grande rivière, le Congo, est pauvre; il y a peu ou pas d’industrie.

Dans le centre, les traces de l’époque coloniale sont encore visibles. Le long des larges rues, on trouve les ruines, ou les restes des pillages successifs, des jolies maisons au style colonial.

Plus de quarante ans de déclin n’ont laissé rien d’entier.

La ville est la capitale de la Province de l’Equateur. Le territoire, deux, trois fois les Pays-Bas, évoque dans le reste du Congo un sentiment compatissant: c’est le pays des chasseurs et des pêcheurs.

Dix kilomètres de Mbandaka se trouve le village de la mission de Bamanya. La piste de sable qui y mène est caractérisée par les légendaires nids de poules qui mettent homme et véhicule à dure épreuve.

Le premier matin de mon séjour, je suis éveillé par des chansons. Une centaine de voix jubilantes d’enfants fait fonction de réveil. Ce sont les enfants de l’école de la Mission qui en guise de gymnastique marchent en galop vers la bourgade voisine. Il est sept heures et demi. Je prends une douche froide, et pendant que je m’habille, la sueur gicle de ma tête.

Les cent cinquante abonnées des Annales Aequatoria doivent patienter: Les plaques d’aluminium pour l’imprimerie à Kinshasa se trouvent depuis des mois à Matadi, la ville portuaire du Congo et attendent le dédouanement. C’est un des multiples problèmes contre lesquelles on a à se battre dans ce pays quand on veut entreprendre quelques chose. “C’est l’Afrique” est l’argument sans réplique.

L’annuaire est publié par le Centre Aequataria, Centre de recherches Culturelles Africanistes. Le Centre possède une bibliothèque avec environ 8.000 livres et 300 titres de périodiques. Des archives linguistiques et historiques (locales) complètent cette documentation spécialisée. Read more

Tiny Bouts Of Contentment. Rare Film Footage Of Graham Greene In The Belgian Congo, March 1959

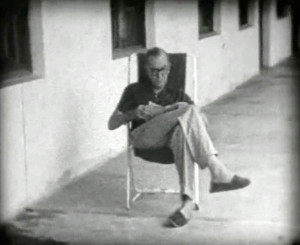

My purpose in this contribution is to present and contextualize the only film footage ever recorded of the novelist Graham Greene (1904-1991) in the Belgian Congo in 1959. The footage was filmed with an 8mm camera, which did not record sound. It belongs to Mrs. Édith Lechat (née Dasnoy;1932-) and her husband, the leprosy specialist Doctor (later Professor) Michel Lechat (1927-2014).

From 1953 through 1960, Dr. Lechat was head of the leper hospital and colony of Iyonda, a village and mission station some 15 kms south of the city of Coquilhatville (now, Mbandaka) in central-western Congo. Greene stayed a number of weeks in Iyonda and other mission stations in the region in search of inspiration, a setting, and material for a new novel. The novel, A Burnt-Out Case, appeared in 1960, and was dedicated to Dr. Lechat. Greene occupied a room in the house of the missionary fathers in Iyonda, but spent long parts of his days with the doctor and his family. The film reached me through the hands of Édith Lechat, who had it transposed to a DVD-playable format, and via my friend Hendrik (a.k.a., “Henri” or “Rik”) Vanderslaghmolen (1921-), who was a missionary in the region at the time. As he was one of the only Belgian missionaries there with some knowledge of English, he often accompanied Graham Greene during his trips from one mission station to another. Rik Vanderslaghmolen and the Lechats are still close friends today.

Much of the information I offer below stems from conversations I had with both Rik Vanderslaghmolen and Édith Lechat in July and August 2013. Regrettably, Dr. Michel Lechat’s poor health condition did not allow me to probe his memory, but an interview he gave for the Brussels-based weekly The Bulletin on the occasion of Greene’s death in 1991 is available (Lechat 1991), as well as a closely similar talk he gave at the 2006 Graham Greene Festival in Berkhamsted, published in the London Review of Books in August 2007 (Lechat 2007). Édith Lechat has given me the kind permission to share the film with the readership of Rozenberg Quarterly and to add the necessary contextual information on both the historical situation and the contents of the film.

6 Comments

From The Web – Enduring Voices

Nearly 80 percent of the world’s population speaks only one percent of its languages. When the last speaker of a language dies, the world loses the knowledge that was contained in that language. The goal of the Enduring Voices Project is to document endangered languages and prevent language extinction by identifying the most crucial areas where languages are endangered and embarking on expeditions to:

Understand the geographic dimensions of language distribution

Determine how linguistic diversity is linked to biodiversity

Bring wide attention to the issue of language loss

When invited, the Enduring Voices Project assists indigenous communities in their efforts to revitalize and maintain their threatened languages.

The Language Hotspots model was conceived and developed by Greg Anderson and David Harrison at the Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages. It is a new way to view the distribution of global linguistic diversity, to assess the threat of language extinction, and to prioritize research. Hotspots are those regions of the world having the greatest linguistic diversity, the greatest language endangerment, and the least-studied languages.

Read more: http://travel.nationalgeographic.com/travel/enduring-voices/

Diversity Education: Lessons For A Just World

Multicultural education, intercultural education, nonracial education, antiracist education, culturally responsive pedagogy, ethnic studies, peace studies, global education, social justice education, bilingual education, mother tongue education, integration – these and more are the terms used to describe different aspects of diversity education around the world. Although it may go by different names and speak to stunningly different conditions in a variety of sociopolitical contexts, diversity education attempts to address such issues as racial and social class segregation, the disproportionate achievement of students of various backgrounds, and the structural inequality in both schools and society. In this paper, I consider the state of diversity education, in broad strokes, in order to draw some lessons from its conception and implementation in various countries, including South Africa. To do so, I consider such issues as the role of asymmetrical power relations and the influence of neoliberal and neoconservative educational agendas, among others, on diversity education. I also suggest a number of lessons learned from our experiences in this field in order to think about how we might proceed in the future, and I conclude with observations on the role of teachers in the current socio-political context.

Multicultural education, intercultural education, nonracial education, antiracist education, culturally responsive pedagogy, ethnic studies, peace studies, global education, social justice education, bilingual education, mother tongue education, integration – these and more are the terms used to describe different aspects of diversity education around the world. Although it may go by different names and speak to stunningly different conditions in a variety of sociopolitical contexts, diversity education attempts to address such issues as racial and social class segregation, the disproportionate achievement of students of various backgrounds, and the structural inequality in both schools and society. In this paper, I consider the state of diversity education, in broad strokes, in order to draw some lessons from its conception and implementation in various countries, including South Africa. To do so, I consider such issues as the role of asymmetrical power relations and the influence of neoliberal and neoconservative educational agendas, among others, on diversity education. I also suggest a number of lessons learned from our experiences in this field in order to think about how we might proceed in the future, and I conclude with observations on the role of teachers in the current socio-political context.

Read more