ISSA Proceedings 2002 – Cultural Influence On The Relative Occurrence Of Evidence Types

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

Persuasive texts, such as advertisements or public information brochures, are written to convince the readers to behave in a certain manner, like buying a DVD-player or stop smoking. These texts are generally characterised by pragmatic argumentation, by which an action is recommended on the basis of its favourable consequences. In order to enhance the persuasive power of these texts, writers can support their claims with different types of evidence, like statistical information or anecdotes. The text writers’ preference for certain types of evidence might be influenced by their cultural background. A cross-cultural corpus study consisting of Dutch and French persuasive brochures will be presented. We will first outline our theoretical framework by discussing the role of pragmatic argumentation (section two) and evidence types (section three) in persuasive communication.

2. Pragmatic argumentation in persuasive communication

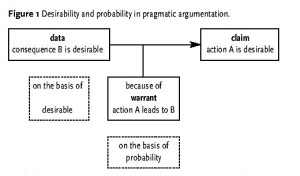

One of the most used argumentation schemes in persuasive communication is pragmatic argumentation. Pragmatic argumentation is commonly regarded as a subcategory of causal argumentation (see, e.g., Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1969; Garssen, 1997). The simplest form of pragmatic argumentation looks like (1):

1. action A leads to consequence B

B is (not) desirable

thus: action A is (not) desirable

Pragmatic argumentation ‘permits the evaluation of an act or an event in terms of its favorable or unfavorable consequences’ (Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1969, 266). There is thus a ‘transfer of a given quality from the consequence to the cause’ (1969, 268). Traveling by train, for example, is a good thing, because it allows avoiding traffic-jams, or – an example of a negative variant – we should not buy this software package, because it will raise our costs by 24 percent.

Feteris (1997, 2002) has developed an instrument for the analysis and evaluation of pragmatic argumentation. The two main critical questions for the evaluation of pragmatic argumentation are about the normative judgment – B is desirable – and about the empirical judgment – A leads to B (Feteris, 1997). It seems that, in everyday persuasive communication, the desirability of the effects is only rarely supported by evidence. This goes for public discourse (Schellens & De Jong, 2000), and especially for advertising (Schellens & Verhoeven, 1994). In advertising, products and services are recommended by paying attention to their benefits. In fact, people usually buy products to reach a certain goal (see, e.g., Gutman, 1982). The desirability of these goals – like freedom, beauty, or comfort – is rarely supported by evidence, because it is self-evident. The probability that an action leads to (un)desirable consequences, however, is often supported by evidence. If a text writer decides to support this probability, he can choose from a large range of evidence types, which we will discuss in the section below.

3. Evidence types in persuasive communication

The concept of evidence is best understood by reference to a model of argumentation that has been developed by Toulmin (1958). This influential model is based on the process of argumentation, which can be divided into three stages. The first stage is the expression of a claim. In the second stage, the defender has to come up with data or evidence to support this claim. In the third stage, finally, the defender has to show that ‘the step [from the data] to the original claim or conclusion is an appropriate and legitimate one’ (Toulmin, 1958, 98). This step is called the warrant, which means ‘if data, then claim’. Argumentation schemes are characterised by their warrant. The warrant of pragmatic argumentation, as we have seen, is ‘if the consequences are desirable, then the cause is desirable too’. A warrant can be supported by a backing; the relationship between the warrant and  its backing is similar to that between the claim and the data. The scheme of pragmatic argumentation applied to the model of Toulmin (1958), in which both the warrant (probability) and the data (desirability) can be supported, is given in figure 1.

its backing is similar to that between the claim and the data. The scheme of pragmatic argumentation applied to the model of Toulmin (1958), in which both the warrant (probability) and the data (desirability) can be supported, is given in figure 1.

Both the desirability and the probability can be supported by what is generally called evidence. There seems to be an agreement in the field of argumentation and persuasion effects research about the meaning of evidence, and the different types of evidence. We define evidence as data – fact or opinion – that is used as an argument to increase adherence of a claim. Evidence types in argumentation studies are usually divided into examples (anecdotal evidence), statistics (statistical evidence), and testimony (source evidence). Experimental studies on the persuasiveness of evidence types have also concentrated on these evidence types, and – more recently (Hoeken, 2001) – on causal evidence. The distinction between these four categories is further supported by the fact that they are connected to the most general argumentation schemes (see Garssen, 1997), and that there is a strong relation with research methods in social science (see Hoeken & Hustinx, this volume).

In research on evidence types, relatively little attention has been paid to the argumentative framework in which the concept of evidence is situated. Evidence types, however, are strongly related to argument types. In short, evidence is data, whereas an argument type is data, warrant and claim. One type of evidence does not necessarily bring about one type of argumentation scheme. The type of argument depends on the claim, as we will show in the light of the following example (2) of anecdotal evidence. Read more

ISSA Proceedings 2002 – Different Types Of Evidence And Quality Of Argumentation In Racist Pamphlets

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

Every day we are confronted with numerous persuasive texts. Apart from the persuasive texts with a commercial purpose, once in a while we are confronted with a type of text intended to convert us to an ideology or a political stance. We may be encouraged to become a member of the foundation for the protection of the badger, to be sympathetic towards the squatters around the corner, to be against taking gravel out of the river Maas, or to expel all foreigners from the country. This paper addresses a type of text belonging to the group last mentioned; it concerns pamphlets coming from right-wing extremist groups(i). The texts may be written by right-wing extremist groups or by individual pamphleteers. In general, they are spread in the street (and, more recently, by internet).

The contents of these pamphlets can be described as more or less racist, in the sense of “Treating (members of) a certain group in an unfavourable way, on the basis of their racial or ethnic origin” (Essed, 1985: 20). In most cases, the pamphleteers argue that unfortunate developments in Dutch society can be attributed to members of another race or another religion, and to the government protecting these people. The solution propagated usually consists in barring or expelling “strangers”, or in silencing the government. In general, one might say that the more outspoken and blatant the racist utterances, the harder to find out the identity of the sender.

Although it is not clear what target group the sender has in mind, it is clear that the pamphlets are not intended solely for the members of the group themselves. After all, the texts are of a persuasive nature, trying to persuade people to perform all kinds of actions.

1.1 The analysis of racist texts

There are many studies on prejudice and racism. Some of them are of a text analytic nature, and therefore relevant to this study. I will briefly discuss two of them.

Van Dijk (1992) investigates, amongst other things, racism and argumentation in tabloid editorials. This type of discourse functions to phrase the opinions of newspaper editors on prominent events. It adresses not only the audience, but also, directly or indirectly, influential news actors, such as the press or politicians. On the grounds of an extensive analysis of two editorials of The Sun and The Mail, exposing the argumentation with respect to content (but not in a schematic way), Van Dijk concludes: “ In other words, the argumentative structure of the editorials is not only a persuasively formulated opinion about the riots and involvement of blacks. Rather, the editorials have a broader political and socio-cultural function, viz., to argue politically for the control over black people, and for the reproduction of white dominance, that is, for white law and order, the marginalization of black community, the legitimation of white neglect in ethnic affairs, and finding excuses for right-wing racism and reaction ”. (p.258).

Mitten and Wodak (1992) provide another text-analytical study on racist texts. They analyse a letter sent by the anti-semitic politician Hödl to his jewish collegue Bronfman by the so-called ‘discourse-historical method’. The subject of the letter is the question whether the name of the Austrian president Waldheim should be added to an American ‘watch list of undesirable aliens’. Bronfman was in favor of adding him. The letter is scrutinized with the help of questions with respect to the construction of the story, the identity of the speakers, the occurrence of stereotypes, and possible evidence of racist opinions. The study shows that Hödl uses anti-semitic stereotypes in his letter to Bronfman, both of an etnical and of a religious nature. Like Van Dijk (1992), this analysis concerns content matter.

The present study makes use of a specific form of text analysis, which focuses on argumentation structure. Do right-wing extremist texts make use of arguments in support of their claims? If so, which type of arguments? Are they convincing?

Many people still have an intuitive aversion against racist texts, or at least they are aware of the fact that it is not politically correct to agree with racist views. So in fact, the claims made in those texts should be well supported in order to take away the aversion, or even to convince the reader of the point of view propagated. Read more

ISSA Proceedings 2002 – Arguing Between The Lines: Grounding Structure In Advertising Discourse

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

The widely accepted view that argumentation ‘uses language to justify or refute a standpoint, with the aim of securing agreement in views’ (van Eemeren et al., 1997, 208), rightly suggests that an advertisement could be considered a text-form variant of argumentative discourse. Like argumentative discourse, the primary goal of advertising discourse is to persuade addressees or potential customers to accept certain viewpoints and ultimately to change their attitude and behaviour.

The present study centres around a prize-winning Dutch press advertisement about organic chickens(i). The advertisement is an instance of consumer advertising that typically ‘is aimed at boosting the consumption of a specific product or service by making potential consumers familiar with the product and building up a positive attitude towards it’ (Gieszinger, 2000, 85). To realize this goal, the organic chicken (OC) advertisement ‘has to convince the reader that the commodity will satisfy some need – or create a need which he has not felt before’ (Vestergaard and Schrøder, 1985, 49). This suggests that the advertisement is also an instance of persuasive discourse that is ‘focused on the decoder and attempts to elicit from him a specific action or emotion or conviction’ (Kinneavy, 1971, 211). In other words, its goal is ‘to move an audience from where it is at the outset of the message to where the source wants it to be at the close of the message’ (McCroskey, 1978, 105).

In persuasive discourse, the encoder, or rather the copywriter, is usually a knowledgeable, authoritative, and credible person. He/she has an informative intent, namely to provide readers with the necessary information about the topic at hand. But he/she also has a persuasive intent, which is to modify readers’- or potential customers’ – opinions, beliefs, attitudes, and eventually actions. In order to realize the persuasive intent, the copywriter would be expected to argue in favour of the advertized product or service.

Advertisements, of course, vary considerably in many respects such as in the way they formulate arguments, the degree of explicitness of these arguments, and the location of arguments in the text. Therefore, it is sometimes difficult to unequivocally determine whether an advertisement, or in fact any other type of text, is argumentative or not. Indeed, ‘the question of whether, and to what extent, an oral or a written discourse is argumentative is not always easy to answer. Sometimes the discourse, or part of it, is presented explicitly as argumentative. Sometimes it is not, even though it has an argumentative function’ (van Eemeren et al., 1996, 290).

The question of how argumentation occurs in discourse is also central to the present study, though not in terms of implicit (vs. explicit) presence of arguments, which means that some disagreed upon issues are not argued about but taken for granted and left for receivers to ‘fill in’ missing arguments. As will become apparent, ‘arguing between the lines’ is used here to describe the occurrence of argumentation in the background of the text(ii). Read more

ISSA Proceedings 2002 – Argumentation Skills Of Secondary School Students In Finland, Hungary and United Kingdom

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

One consequence of the strengthening integration in Europe is that people of different nationalities become closer to each other, sharing increasingly common interests in terms of both economical and cultural change and development. The rapidly developing information and communication technology, and the access to Internet network facilities in particular, has facilitated and increased international communication. The citizens of today’s network society are increasingly required to critically examine current societal issues from different points of view, to form reasoned opinions and to engage in public debate relating to them. Many of the current societal questions are cross-national in nature such as protection of nature, building of new nuclear power stations, production of genetically modified food and gender equality. One important aim of current secondary school education is to assist young citizens, in the age just before they become real political actors, in acquiring the necessary knowledge and skills to be able to participate in debates concerning such societal questions (see SCALE-project, 2002). Argumentation and critical thinking skills are needed in order to successfully engage in debates by means of both spoken and written language. Thus, contemporary secondary school education should particularly emphasise the teaching of these skills.

According to van Eemeren and Grootendorst (1999), the aim of an argumentative dialogue is to resolve differences of opinion by reaching agreement through critical discussion about the acceptability or unacceptability of the various standpoints. When engaging in critical argumentative dialogue, one should be able to present well grounded arguments for his/her opinions, put forward counterarguments and refute criticism by other participants. In this study, however, argumentation skills are investigated by focusing on skills that appear when secondary school students express their thoughts literary in non-dialogical situations. Previous research (e.g. Marttunen, 1994) has shown that argumentation skills can be divided into subskills which exist, at least to some degree, independently. Such skills are the skill to analyse argumentative texts and the skill to compose one’s own arguments. Experiences gained from other studies have shown that in addition to analysis of argumentative texts (Oostdam & Eiting, 1990; Ryan & Norris, 1990; Marttunen, 1997) and composition of one’s own arguments (McCann, 1989; Oostdam & Emmelot, 1990; Marttunen, 1997), commenting on argumentative writings (Marttunen & Laurinen, 2001), and judging the validity of an argument in multiple-choice tasks (Oostdam & De Glopper, 1998) are other appropriate ways of measuring argumentation skills.

This article [i] investigates secondary schools students’ argumentation skill in Finland, Hungary and the United Kingdom. The aforementioned four task types representing various approaches to argumentation in non-dialogical situations were used in this study.

2. Argumentation in secondary school curricula in Finland, Hungary and the United Kingdom

Although argumentation skills are widely considered as important in order to educate school pupils to become active and critical citizens who are able to engage in public debate, the possibility for teaching argumentation to new generations is largely dependent on the school systems and emphasis in curricula in different countries. In Finland the national Framework Curriculum and the municipal level curriculum for secondary schools strongly emphasize the need for teaching students critical thinking and argumentation skills. One of the aims of the secondary school included in these documents is to educate students to become independently thinking critical citizens (see Framework curriculum…, 1994). The study system in Finnish secondary school is course-based and not bound up with year-grades. The system provides the individual schools with good opportunities to allocate teaching resources themselves and to concentrate on areas of their specialisation. The obligatory courses for secondary schools in mother tongue include studies and learning material significant from the point of view of argumentation. In addition to the exercises in oral debate and argumentative writing, the course contents include also studies relating to different aspects of the argumentative power of language in various areas of social life. Teachers can also freely select authentic teaching material from newspapers and other sources. The central idea of the Finnish secondary school curriculum is flexibility, which provides the schools with possibilities to also organise cross-disciplinary studies of argumentation and critical thinking. Read more

ISSA Proceedings 2002 – Argument Density And Argument Diversity In The Licence Applications Of French Provincial Printers, 1669 – 1781

In this pilot project we survey the kinds of argumentation used by the men and women in provincial France who applied for royal licences to run printing houses in the ninety- year period, 1669 – 1781.

In this pilot project we survey the kinds of argumentation used by the men and women in provincial France who applied for royal licences to run printing houses in the ninety- year period, 1669 – 1781.

At the end of the ancien régime in France the appointment or licensing of a printer was a complex process that involved input from a number of high officials in the royal government as well as from local officials in the town the printer was to work. In 1780, for example, the appointment of printer in Dijon involved the Keeper of the Seals, the Director of the Book trade, the Intendant, the Lieutenant of police and the Inspector of the Book trade as well as the officers and other members of the printers’ guild in Dijon(i).These men were all following elaborate rules for printer appointment laid out in detail by royal decree in 1777. These procedures represented the mature development of the French Crown’s century-long determination to license – and consequently decide – who would hold the 310 printer positions in the realm(ii).

Licensing began in 1667 when Colbert banned all new printers from setting up businesses without special approval(iii). In the years following 1667 some printers in some towns saw great advantages (notably increased market share) to be gained from the royal licensing policies and moved to see that the ban was implemented(iv). In other towns the licensing requirement went unnoticed until 1704 when Crown officials set quotas on the numbers of printers allowed in each town and charged the Lieutenants of police with seeing that they were respected. In the subsequent decades (and not without resistance) the number of printers was forcibly reduced. By 1739 – when the rules were tightened and the number of printers was again reduced – there was wide acceptance of printer licensing. In 1759 the numbers were further reduced and in 1777 the procedures for printer appointment were clarified.

At the end of the ancien régime there seems to have been considerable agreement between the candidates, the guild officials, and the royal officials, on what constituted a good printer. On the one hand, they were all thinking to some extent in terms of guild entrance requirements that could be found in different statutes in the seventeenth century, and these were stated in an important 1723 decree that governed Parisian printers and was then extended in 1744 to the rest of the realm(v). At the core of this understanding were the following requirements: four years of apprenticeship were needed and three consecutive years as a journeyman. Candidates had to be twenty years of age, know Latin and be able to read Greek, and produce a certificate from the rector of the university to this effect. Sons of masters were exempt from apprenticeship and journeyman requirements. All candidates including sons of printers had to submit to an examination before the guild officers.

These requirements were understood by everyone but satisfying only these was not sufficient to obtain a printer position in eighteenth-century France. Candidates covered all the required bases in their applications and added yet more evidence of suitability. Defay, our Dijon example from 1780, was a son of a printer and, although he did not need to complete a stint as a journeyman, he made it clear that he had vast experience directing a printing house. Also, he had his curé produce a certificate saying that he was a man of probity. The Lieutenant of police in Dijon in his letters made two points about Defay: he had been in printing all his life, and his conduct was irreproachable. Given the heightened fears of the clandestine book trade in the reign of Louis XVI, it is unlikely that this last comment meant anything but that he could be deemed loyal and reliable.

This understanding of what made for a good printer in the reign of Louis XVI (1774-1792) was not firmly fixed in the earlier reign of Louis XIV (1643-1715). The hypothesis of our present essay is that, in the minds of the applicants, the conception of what constituted ‘a good printer’ was forged over the course of the eighteenth century, especially in the early years. The evidence we will consider for our hypothesis is the changing patterns of argumentation recorded in samples of the licensing decrees from 1669 – 1781. Read more

ISSA Proceedings 2002 – Evidence In Interpersonal Influence

Abstract

Abstract

The study is an exploration into the types of evidence used in interpersonal influence. Respondents described either an interpersonal episode where they gave evidence or where they challenged another to give evidence. The respondents then rated the degree of intimacy in the relationship, the persuasive result, types of evidence used, and the influence the other person had. A factor analysis of types of evidence resulted in three factors: external evidence, narrative accounts, and common information. Respondents thought they used external types of evidence while others relied more on narrative accounts. Personal testimony and narrative accounts were regarded as more common in persuasive encounters than in non-persuasive encounters. Further, influential others were thought to use a greater variety of evidence types.

1. Introduction

This paper represents an exploration into the way that people incorporate evidence into their conversations in interpersonal relationships and how they process that evidence. Numerous conversational arguments take place over the life of a relationship. The level of care and concern that exists in the dynamics of particular dyads probably has an impact on the way the arguments are carried out (Brockriede,1972). Authors such as Alberts (1989), Benoit and Benoit (1990), Hample, Benoit, Houston, Purifoy, VanHyfte, and Wardell (1999), Jackson and Jacobs (1981), Johnson and Roloff (1998), Sprecher (1986; 2001), Weger (2001) and others, have chosen to investigate argument and how it is processed from an interpersonal communication perspective. Unique insights about evidence need to be pursued in light of the fact that most of the research about evidence has been done in the more traditional forensic and deliberative settings. The decision about the need to incorporate evidence into conversations has not received enough attention over the years to enable researchers to create an accurate picture of how this process takes place.

Various questions about how better relationships are characterized have been looked at in somewhat limited ways. Benoit and Benoit (1990) looked at the ways that respectful partners were careful to present full reasoning and evidence. Others have explored arguments where they are coupled with a commitment to resolvability of conflicts (Johnson & Roloff, 1998) or how the arguments are performed in a way unique to the couple (van Eemeren, & Grootendorst, 1991).

Recent work on narratives as evidence inspires the thought that there may be differences in the forms of evidence common in interpersonal communication versus policy discourse. In the past there has been inconsistency when statistical and narrative (or story) evidence effects have been compared. Baesler (1997) and Baesler & Burgoon (1994) found that a meaningful story in support of an argument appears to be as persuasive as meaningful statistics for a moderately involved audience. But Allen and Preiss (1997) indicated that statistical data wins out over pithy tales in the persuasion arena. O’Keefe (1998) looked at how specific quantification needs to be. Slater and Rouner (1996) found effects to vary with the initial position of the message recipients. Kopfman, Smith, Ah Yun, and Hodges (1998) claimed that “a main effect for evidence type [was found] such that statistical evidence messages produced greater results in terms of all the cognitive reactions, while narratives produced greater results for all of the affective reactions”(p. 279). In short, it appears that the advocate is best advised to use both statistical and narrative evidence. Could it be, however, that the effects of different forms of evidence varies with the relationship between the advocate and the audience?

This study is an effort to evaluate message strategies in the context of the interpersonal relationship and the message reception environment. Specifically, the idea of interpersonal influence and dominance was added to the equation to try to understand the dynamic of interpersonal persuasion. This dominance was viewed as a relational state that includes behavioral and interactional aspects and that reflects influence over others actions (Burgoon, Johnson & Koch, 1998). Read more