Estamos bien en el refugio Los 33 – De nasleep van de Chileense mijnramp

In 2010 werd het Chileense Copiapó wereldnieuws. Vlak bij deze stad kwamen op 5 augustus 2010 33 mijnwerkers vast te zitten in de San José mijn. 69 dagen verbleven zij op bijna zevenhonderd meter diepte. Voor het oog van miljoenen tv-kijkers werden zij, op 12 en 13 oktober 2010, één voor één bevrijd. ‘Los 33’ werden als helden onthaald en kregen uitnodigingen om onder meer Disney World in Amerika en voetbalwed-strijden van Real Madrid en Manchester United te bezoeken. Een poos na de ramp gaat het met de ene mijnwerker een stuk beter dan met de ander.

Jimmy Sánchez zit voornamelijk thuis op de bank. Dan staart hij wat voor zich uit en denkt na. Over de tijd die hij doorbracht in de San José mijn. ,,Ik kan alleen maar aan de ramp denken,” zegt de jongste van de 33 mijnwerkers. De nu 21-jarige Chileen heeft het zwaar, is zichzelf kwijt. ,,Vroeger was ik vrolijk en genoot ik van mijn vrienden en familie. Nu voel ik me onbegrepen en wanhopig en ben ik liever alleen. Ik ben nerveus, kan me niet goed concentreren en word soms uit het niets woedend. Ook zijn er dagen dat ik niets anders doe dan huilen. Deze hele situatie maakt me wanhopig en ik weet niet wat te doen.” Read more

Terra Firma: Ashore in the Bay of Strangers

Friday, 25 August 1995 – “Bosun – topside!” The Captain’s command over the intercom aroused me from a deep sleep. Henri, jumping from his cot, rushed out to film the action on deck. Soon the muffled rattling of the anchor chain reverberated throughout the ship: we were dropping anchor. Slowly, I got up. Fleetingly, ever so fleetingly, a wave of revulsion suffused my body, and I tried not to think about what was outside: a fog-shrouded, ice-cold sea and a huge, empty island. I glanced at my watch: 7:15 a.m. Through the porthole I could see a calm sea, light blue under a low, grey sky. If this was Ivanov Bay, the grave search party would go ashore. If it wasn’t, only the Captain might know where on earth we may be. I got dressed and hurried outside. In the light, drizzly mist that engulfed the ship, Jerzy and Bas were siphoning gasoline into lemonade bottles from a big, rusty fuel barrel on the foredeck, using a rubber hose. Inside, the breakfast table had been set, but there was no time to eat. The landing of the grave-searchers was busily being prepared, as Boyarsky was threatening that the sea might soon get rough again. Only George, with aristocratic unconcern, sat sipping a cup of tea in the otherwise empty mess room. The corridors teemed with foot traffic. The hum of electric motors resonated through the steel vessel as the deck crane deposited a huge stack of wooden beams and planks from the hold into the landing craft. For protection against bears, the Ivanov Bay group would be constructing a hut for their stay. On deck, the atmosphere was frenzied and tension was palpable, with good-byes adding to the din of cargo handling.

Friday, 25 August 1995 – “Bosun – topside!” The Captain’s command over the intercom aroused me from a deep sleep. Henri, jumping from his cot, rushed out to film the action on deck. Soon the muffled rattling of the anchor chain reverberated throughout the ship: we were dropping anchor. Slowly, I got up. Fleetingly, ever so fleetingly, a wave of revulsion suffused my body, and I tried not to think about what was outside: a fog-shrouded, ice-cold sea and a huge, empty island. I glanced at my watch: 7:15 a.m. Through the porthole I could see a calm sea, light blue under a low, grey sky. If this was Ivanov Bay, the grave search party would go ashore. If it wasn’t, only the Captain might know where on earth we may be. I got dressed and hurried outside. In the light, drizzly mist that engulfed the ship, Jerzy and Bas were siphoning gasoline into lemonade bottles from a big, rusty fuel barrel on the foredeck, using a rubber hose. Inside, the breakfast table had been set, but there was no time to eat. The landing of the grave-searchers was busily being prepared, as Boyarsky was threatening that the sea might soon get rough again. Only George, with aristocratic unconcern, sat sipping a cup of tea in the otherwise empty mess room. The corridors teemed with foot traffic. The hum of electric motors resonated through the steel vessel as the deck crane deposited a huge stack of wooden beams and planks from the hold into the landing craft. For protection against bears, the Ivanov Bay group would be constructing a hut for their stay. On deck, the atmosphere was frenzied and tension was palpable, with good-byes adding to the din of cargo handling.

Freed from all its cables, our landing craft, a red steel barge five meters long, danced merrily atop the waves. Once the entire Ivanov gang had climbed down the rope ladders, the droning plashkot sailed rapidly into the haze. Bundled up in gear as if ready to go ashore myself, I stood in a light rain atop Kiriev’s bridge and followed the progress of the landing through binoculars. A trio of long, rustbrown walruses glided by the red craft through the pale blue sea. It was easy to distinguish their bristling snouts, which spit out a spray of condensation and water when the animals are surfacing. It was +4°C. Novaya Zemlya was just a dark strip of land, the elevations above ca. 100 m disappearing into the low clouds. There was little snow.

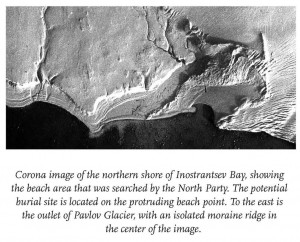

By 11:15 a.m., the Ivanov group was ashore. The landing craft delivered a second load and was hoisted aboard. Kiriev raised anchor, but would not sail towards Ice Harbor. It had been decided to seek shelter from a new storm in Inostrantsev Bay, on the west coast of the island. Excitement swept over the ship when, at noon, we saw the first unobtrusive iceberg float by: the entire oyage so far had not provided this many sights. The silent flotilla of blue sculptures grew by the hour, indicating the proximity of calving glaciers. Our arrival in Inostrantsev Bay was estimated for 3:00 p.m. The plan calls for a reconnaissance sortie with two groups along the beaches of the bay, to search for cairns. Boyarsky requests that we be specifically alert for objects indicating the presence of the ancient Pomors and the Nazis, who operated in greatest secrecy on these shores during their Arctic campaigns. The approaching landing put us back on the alert. Bas distributed ammunition for the rifles and reviewed the arms discipline. “Should a polar bear come after us and we decide to fire at him,” he instructed us, “we’ll follow our firing-range routine. The shooter kneels down and someone else counts the bear’s approach: fifty meters… forty meters… thirty meters… Don’t stare at the bear, but focus on his chest or on his shoulder. There will be three cartridges in the magazine. For reasons of safety, do not keep a cartridge in the chamber. Remember, the second man keeps additional ammo at the ready.”

Self-sufficiency is imperative for one venturing out in the Arctic, and it was high time to get my gear in order. (“Coming along?” Anton, our film director, would tell the viewer. Small kids start crying, young women turn off the TV.) What do I need? After polar bears, the unpredictable weather, which can change from quiet to severe in half an hour, is the greatest challenge. The land is barren and provides no shelter. There is no snow in which the stranded traveler could dig a shelter against the piercing winds. To be lightly equipped and able to move about swiftly, I packed the thin, reinforced Gore-Tex cover of the Navy-issue sleeping bag and a small stove, with a one-liter bottle of gasoline, enough for two weeks. High-grade gasoline is harder to come by in these parts of the world than diesel or kerosene but more practical because kerosene fuel oil has a flash point well above 40°C and won’t ignite easily in low-temperature environs. I took my down jacket, wrapped in a plastic bag, so I could leave my sleeping bag on board. I took wax for my boots, packages of instant soup, chocolate milk, and mashed potatoes. There would be sufficient meltwater on land, but just to be sure, I filled my canteen. On a waist belt, I carried the dagger and a pouch containing flare gun, GPS, a set of waterproof-packed batteries, a notebook with waterproof paper, and a pencil. I took some extra film and decided where to put everything: the rain gear fortunately has plenty of zippered pockets to stow away the many little items I need to keep track of.

The sea was calm: smooth as glass. The landing craft glided over in fifteen minutes and at 4:00 p.m. ground onto the steep, gravel beachfront. The sailors kept the engine running to maintain a solid lock while we disembarked. In clouds of smoke and steam, we climbed the steep ridge of loose gravel. Then, after reversing the propeller’s motion, the plashkot quickly retreated into the fog.

ISSA Proceedings 2006 ~ Pragma-Dialectics And The Function Of Argumentation

1. Introduction: Pragma-Dialectics and the Aims of this Paper

1. Introduction: Pragma-Dialectics and the Aims of this Paper

During the last 25 years Frans van Eemeren and Rob Grootendorst have very impressively developed Pragma-Dialectics, i.e. a consensualistic theory of argumentative discourse, which sees the elimination of a difference of opinion as the aim of such discourses and of argumentation. Currently this is the most famous and most discussed approach in argumentation theory in the world.

In what follows I will discuss Pragma-Dialcetics mainly from an epistemological standpoint, i.e. what this theory has to tell us with respect to acquiring true or justified beliefs and knowledge.

Technical note: The discussion rules are the constructional core of Pragma-Dialectics; in addition to a few material changes and to stylistic improvements, these rules have undergone a change in numbering. In this text I will refer to their first English version (E&G 1984, p. 151-175) as “Ro1” etc. (“original (or old) rule no. 1”) and to their most recent statement (E&G 2004, pp. 135-157) as “Rs1” etc. (“Rule in ‘Systematic Theory of Argumentation’ no. 1”). The material changes regard, first, the possibilities of defending (or attacking) a premise (Ro9/Rs7 (E&G 1984, p. 168; 2004, p. 147 f.)); the originally included possibility of common observation has been deleted – which is surprising – and the originally lacking possibility of argumentatively defending a premise included, which is a clear improvement. The second and most important change concerns the argument schemes that may be used for defending a claim: originally only deductive arguments were permitted now non-deductive argument schemes have been added (Ro10/Rs8 (E&G 1984, p. 169; 2004, p. 150)) – a substantial improvement. The following discussion usually refers only to the best version.

2. The Aim of Argumentation and Argumentative Discourse: Elimination of a Difference of Opinion

The whole approach of Pragma-Dialectics is constructed starting from one central theorem about the function of argumentative discourse and argumentation in general. The aim of argumentative discourse and of argumentation, as these are seen and constructed by Pragma-Dialectics, is to eliminate a difference of (expressed) opinion (e.g. E&G 1984, p. 1; 1992, xiii; p. 10; 2004, pp. 52; 57; Eemeren et al. 1996, p. 277) or to resolve a dispute – where “dispute” is understood as: expressed difference of opinion (e.g. E&G 1984, pp. 2; 3; 151). This resolution has taken place if the participants both explicitly agree about the opinion in question. The central task of the theory is to develop rules for rational discussions or discourses; and the value of the rules to be developed is regarded as being identical to the extent to which these rules help to attain the goal of resolving disputes (E&G 1984, pp. 151; 152; cf. 2004, pp. 132-134).

This, obviously, is a consensualistic conception of argumentative discourse and of argumentation, which aims at an unqualified consensus, i.e. a consensus that is not subjected to further conditions.[i] Consensualism defines a clear aim for argumentation and argumentative discourse, which can be the basis for developing a complete argumentation theory, including criteria for good argumentation, good discourse, theory of fallacies, theory of argumentation interpretation, etc. Thus, consensus theory in general, and Pragma-Dialectics in particular, is a full-fledged approach to argumentation theory. Similar and competing full-fledged approaches are, first, the rhetorical approach, which sees convincing an addressee, i.e. creating or raising an addressee’s belief in a thesis, as the aim of argumentation (e.g. Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca 1958; Hamblin 1970; Tindale 2004), and, second, the epistemological approach, which sees generating the addressee’s justified belief in the argumentation’s thesis as the standard function of argumentation (e.g. Biro & Siegel 1992,; Feldman 1994; Goldman 1999, ch. 5; Johnson 2000; Lumer 1990; 1991; 2005/2006; Siegel & Biro 1997). As opposed to epistemological theories, both consensus theory and rhetoric aim at an unqualified belief (though in Pragma-Dialectics this is more an expression of a belief than the belief itself); but consensus theory then, unlike rhetoric, requires that both participants share this opinion. Read more

De onzichtbaarheid voorbij – De collectieve rechten van inheemse volkeren in Peru en Bolivia – I

Inleiding

Wie in Nederland aan Peru en Bolivia denkt, ziet de typische beelden voor zich van inheemse vrouwen met twee vlechten, kleurige rokken, en een hoed op het hoofd. Hoewel inderdaad in beide landen een groot deel van de bevolking inheems is, zijn deze mannen en vrouwen eeuwenlang onzichtbaar geweest op het politieke toneel. Dankzij de toegenomen aandacht voor de inheemse rechten op internationaal niveau en de versterking van de inheemse organisaties van onderaf, hebben de inheemse volkeren een steeds grotere rol in nationale processen verkregen. Opgenomen worden in de bestaande structuren is echter niet genoeg. De inheemse volkeren bevorderen nieuwe processen om vanuit hun eigen culturele en etnische diversiteit mee te kunnen besluiten. Zij willen geen van buitenaf opgelegde ontwikkelingsmodellen aannemen, maar zelf hun Buen Vivir(i)bepalen. Op deze manier dragen de inheemse volkeren bij aan een nieuwe uitleg van concepten als natiestaat, democratie en burgerschap. Read more

De onzichtbaarheid voorbij – De collectieve rechten van inheemse volkeren in Peru en Bolivia – Deel II

4. Peru: de strijd om burgerschap

Peru heeft de afgelopen jaren prachtige economische groeicijfers gepresenteerd, maar daar heeft het grootste deel van de bevolking weinig van gemerkt. Het economische beleid is vooral gestoeld op het snel verkopen van de vele grondstoffen die het land rijk is en heeft daarbij weinig oog voor mens noch milieu. Met name de multinationale mijnbouw- en petroleumbedrijven zorgen voor een snel toenemend aantal conflicten.

In dit hoofdstuk benoem ik een aantal factoren die de specifieke situatie van Peru tekenen. Om te beginnen heeft Peru veel meer inwoners dan Bolivia, namelijk ruim 28 miljoen, waarvan rond de 9 miljoen (34,41 procent) onderdeel uit maken van de inheemse volkeren. De grootste groep inheemsen zijn de Quechua’s, verspreid over de Andesgebieden, die in Peru de Sierra genoemd worden. Vervolgens komen de Aymara’s, die hun gemeenschappen op de hoogvlaktes rond het Titicacameer hebben. In de Amazone wonen maar liefst 65 verschillende inheemse volkeren, waarvan minstens elf in gekozen afzondering of met zeer weinig extern contact. De meest bekende Amazonevolkeren zijn de Ashanínka’s, Awajún en Matsiguenga’s (caoi 2008b; UNIFEM 2008:35). Naast de inheemse volkeren vormen de zogenaamde Afroperuanos, afstammelingen van Afrikaanse slaven, ook een aanzienlijk deel van de Peruaanse bevolking.

Bijna een derde van de bevolking woont in Lima, en het lijkt soms alsof Peru dáár voor de politici, de economische elite en de media ophoudt. Zij leven in Lima met hun rug naar de Andes en de Amazone en hebben weinig interesse voor wat er in de rest van het land gebeurt.

The Innovation of Population Forecasting Methodology in the Inter-war Period: The Case of the Netherlands

4.1 Introduction

4.1 Introduction

The foundations of the model of population dynamics that was to dominate population forecasting methodology throughout the greater part of the 20th century were laid by the English economist Edwin Cannan (1861-1935). By the end of the 1930s, it had become the new standard model for forecasting national populations. After the Second World War, the model became known as the Cohort-Component Projection Model (CCPM).[i]

However, this does not mean that the introduction and general acceptation of the new methodology was a matter of veni, vidi, vici. On the contrary, almost three decades passed between its emergence in 1895 and its reinvention and general application for national population forecasting purposes in the mid-1920s.

Read more